NPS Form 10 900 OMB No. 1024 0018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chicago Neighborhood Resource Directory Contents Hgi

CHICAGO NEIGHBORHOOD [ RESOURCE DIRECTORY san serif is Univers light 45 serif is adobe garamond pro CHICAGO NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY CONTENTS hgi 97 • CHICAGO RESOURCES 139 • GAGE PARK 184 • NORTH PARK 106 • ALBANY PARK 140 • GARFIELD RIDGE 185 • NORWOOD PARK 107 • ARCHER HEIGHTS 141 • GRAND BOULEVARD 186 • OAKLAND 108 • ARMOUR SQUARE 143 • GREATER GRAND CROSSING 187 • O’HARE 109 • ASHBURN 145 • HEGEWISCH 188 • PORTAGE PARK 110 • AUBURN GRESHAM 146 • HERMOSA 189 • PULLMAN 112 • AUSTIN 147 • HUMBOLDT PARK 190 • RIVERDALE 115 • AVALON PARK 149 • HYDE PARK 191 • ROGERS PARK 116 • AVONDALE 150 • IRVING PARK 192 • ROSELAND 117 • BELMONT CRAGIN 152 • JEFFERSON PARK 194 • SOUTH CHICAGO 118 • BEVERLY 153 • KENWOOD 196 • SOUTH DEERING 119 • BRIDGEPORT 154 • LAKE VIEW 197 • SOUTH LAWNDALE 120 • BRIGHTON PARK 156 • LINCOLN PARK 199 • SOUTH SHORE 121 • BURNSIDE 158 • LINCOLN SQUARE 201 • UPTOWN 122 • CALUMET HEIGHTS 160 • LOGAN SQUARE 204 • WASHINGTON HEIGHTS 123 • CHATHAM 162 • LOOP 205 • WASHINGTON PARK 124 • CHICAGO LAWN 165 • LOWER WEST SIDE 206 • WEST ELSDON 125 • CLEARING 167 • MCKINLEY PARK 207 • WEST ENGLEWOOD 126 • DOUGLAS PARK 168 • MONTCLARE 208 • WEST GARFIELD PARK 128 • DUNNING 169 • MORGAN PARK 210 • WEST LAWN 129 • EAST GARFIELD PARK 170 • MOUNT GREENWOOD 211 • WEST PULLMAN 131 • EAST SIDE 171 • NEAR NORTH SIDE 212 • WEST RIDGE 132 • EDGEWATER 173 • NEAR SOUTH SIDE 214 • WEST TOWN 134 • EDISON PARK 174 • NEAR WEST SIDE 217 • WOODLAWN 135 • ENGLEWOOD 178 • NEW CITY 219 • SOURCE LIST 137 • FOREST GLEN 180 • NORTH CENTER 138 • FULLER PARK 181 • NORTH LAWNDALE DEPARTMENT OF FAMILY & SUPPORT SERVICES NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY WELCOME (eU& ...TO THE NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY! This Directory has been compiled by the Chicago Department of Family and Support Services and Chapin Hall to assist Chicago families in connecting to available resources in their communities. -

Lorado Taft Midway Studios AND/OR COMMON Lorado Taft Midway Studios______I LOCATION

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ___________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ | NAME HISTORIC Lorado Taft Midway Studios AND/OR COMMON Lorado Taft Midway Studios______________________________ I LOCATION STREET & NUMBER University of Chicago, 6016 Ingleside Avenue —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Chicago __ VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Illinois 05 P.onV CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT —PUBLIC XXOCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) ?_PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS ^-EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE _ SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED _ YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER. (OWNER OF PROPERTY NAMEINAMt University of Chicago, (Office of Special Events, Administration STREET & NUMBER 5801 Ellis Avenue CITY. TOWN STATE VICINITY OF Chicago T1 1 inr>i' a LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEps.ETc. Cook County Recorder and Registrat of Titles STREET & NUMBER 118 North Clark CITY. TOWN STATE Chicago Tllinm', REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE none known DATE — FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE YY —EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED —UNALTERED —ORIGINAL SITE XXQOOD —RUINS XXALTERED —MOVED DATE_______ —FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Lorado Taft's wife, Ada Bartlett Taft y described the Midway Studios in her biography of her husband, Lorado Taft, Sculptor arid Citizen; In 1906 Lorado moved his main studio out of the crowded Loop into a large, deserted brick barn on the University of Chicago property on the Midway. -

Chicago from 1871-1893 Is the Focus of This Lecture

Chicago from 1871-1893 is the focus of this lecture. [19 Nov 2013 - abridged in part from the course Perspectives on the Evolution of Structures which introduces the principles of Structural Art and the lecture Root, Khan, and the Rise of the Skyscraper (Chicago). A lecture based in part on David Billington’s Princeton course and by scholarship from B. Schafer on Chicago. Carl Condit’s work on Chicago history and Daniel Hoffman’s books on Root provide the most important sources for this work. Also Leslie’s recent work on Chicago has become an important source. Significant new notes and themes have been added to this version after new reading in 2013] [24 Feb 2014, added Sullivan in for the Perspectives course version of this lecture, added more signposts etc. w.r.t to what the students need and some active exercises.] image: http://www.richard- seaman.com/USA/Cities/Chicago/Landmarks/index.ht ml Chicago today demonstrates the allure and power of the skyscraper, and here on these very same blocks is where the skyscraper was born. image: 7-33 chicago fire ruins_150dpi.jpg, replaced with same picture from wikimedia commons 2013 Here we see the result of the great Chicago fire of 1871, shown from corner of Dearborn and Monroe Streets. This is the most obvious social condition to give birth to the skyscraper, but other forces were at work too. Social conditions in Chicago were unique in 1871. Of course the fire destroyed the CBD. The CBD is unique being hemmed in by the Lakes and the railroads. -

Pittsfield Building 55 E

LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT Pittsfield Building 55 E. Washington Preliminary Landmarkrecommendation approved by the Commission on Chicago Landmarks, December 12, 2001 CITY OFCHICAGO Richard M. Daley, Mayor Departmentof Planning and Developement Alicia Mazur Berg, Commissioner Cover: On the right, the Pittsfield Building, as seen from Michigan Avenue, looking west. The Pittsfield Building's trademark is its interior lobbies and atrium, seen in the upper and lower left. In the center, an advertisement announcing the building's construction and leasing, c. 1927. Above: The Pittsfield Building, located at 55 E. Washington Street, is a 38-story steel-frame skyscraper with a rectangular 21-story base that covers the entire building lot-approximately 162 feet on Washington Street and 120 feet on Wabash Avenue. The Commission on Chicago Landmarks, whose nine members are appointed by the Mayor, was established in 1968 by city ordinance. It is responsible for recommending to the City Council that individual buildings, sites, objects, or entire districts be designated as Chicago Landmarks, which protects them by law. The Comm ission is staffed by the Chicago Department of Planning and Development, 33 N. LaSalle St., Room 1600, Chicago, IL 60602; (312-744-3200) phone; (312 744-2958) TTY; (312-744-9 140) fax; web site, http ://www.cityofchicago.org/ landmarks. This Preliminary Summary ofInformation is subject to possible revision and amendment during the designation proceedings. Only language contained within the designation ordinance adopted by the City Council should be regarded as final. PRELIMINARY SUMMARY OF INFORMATION SUBMITIED TO THE COMMISSION ON CHICAGO LANDMARKS IN DECEMBER 2001 PITTSFIELD BUILDING 55 E. -

Chicago Venue Portfolio

CHICAGO2016 VENUE PORTFOLIO 1750 W. LAKE STREET CHICAGO, IL 60612 [email protected] 773.880.8044 PARAMOUNTEVENTSCHICAGO.COM Paramount Events is ready to help you plan a spectacular event with a delicious SET menu, but to truly make an impact, the perfect backdrop is absolutely essential. THE We have connections at some of the best venues in Chicago, including The Smith on Lake, our own private space that guarantees dedicated service and personalized attention. SCENE You’re welcome to explore the following pages, but don’t forget – we’re here for you! We know every location inside and out and will be happy to offer our suggestions as a guide. ENJOY! TABLE OF 19th Century Club 1 Garfield Park Conservatory 45 Park West 90 1st Ward at Chop Shop 2 Glessner House Museum 46 Parliament 91 CONTENTS 345 North 3 Goodman Theatre 47 Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum 92 360 Chicago 4 Gruen Galleries 48 Pittsfield Building 93 63rd Street Beach House 5 Harold Washington Library Center 49 Pleasant Home 94 A New Leaf 6 Harris Theatre 50 Portfolio Annex 95 Anita Dee Charters 7 Highland Park Community House 51 Power House 96 Aragon Ballroom 8 Hilton | Asmus Contemporary 52 Prairie Production 97 Artifact Events 9 Hinsdale Community House 53 Primitive Art 98 Auditorium Theatre of Roosevelt University 10 Humboldt Park & Boat House 54 Pritzker Military Museum & Library 99 Baderbräu 11 Ida Noyes Hall at University of Chicago 55 Promontory Point 100 Bentley Gold Coast 12 Ignite Glass Studios 56 Ravenswood Event Center 101 Berger Park 13 International -

This Is Chicago

“You have the right to A global city. do things in Chicago. A world-class university. If you want to start The University of Chicago and its a business, a theater, namesake city are intrinsically linked. In the 1890s, the world’s fair brought millions a newspaper, you can of international visitors to the doorstep of find the space, the our brand new university. The landmark event celebrated diverse perspectives, backing, the audience.” curiosity, and innovation—values advanced Bernie Sahlins, AB’43, by UChicago ever since. co-founder of Today Chicago is a center of global The Second City cultures, worldwide organizations, international commerce, and fine arts. Like UChicago, it’s an intellectual destination, drawing top scholars, companies, entrepre- neurs, and artists who enhance the academic experience of our students. Chicago is our classroom, our gallery, and our home. Welcome to Chicago. Chicago is the sum of its many great parts: 77 community areas and more than 100 neighborhoods. Each block is made up CHicaGO of distinct personalities, local flavors, and vibrant cultures. Woven together by an MOSAIC OF extensive public transportation system, all of Chicago’s wonders are easily accessible PROMONTORY POINT NEIGHBORHOODS to UChicago students. LAKEFRONT HYDE PARK E JACKSON PARK MUSEUM CAMPUS N S BRONZEVILLE OAK STREET BEACH W WASHINGTON PARK WOODLAWN THEATRE DISTRICT MAGNIFICENT MILE CHINATOWN BRIDGEPORT LAKEVIEW LINCOLN PARK HISTORIC STOCKYARDS GREEK TOWN PILSEN WRIGLEYVILLE UKRAINIAN VILLAGE LOGAN SQUARE LITTLE VILLAGE MIDWAY AIRPORT O’HARE AIRPORT OAK PARK PICTURED Seven miles UChicago’s home on the South Where to Go UChicago Connections south of downtown Chicago, Side combines the best aspects n Bookstores: 57th Street, Powell’s, n Nearly 60 percent of Hyde Park features renowned architecture of a world-class city and a Seminary Co-op UChicago faculty and graduate alongside expansive vibrant college town. -

Hoops in the Hood 2019 Summer Schedule

HOOPS IN THE HOOD ▪ 2019 SUMMER SCHEDULE 13th Annual Cross-City Tournament with LISC Chicago and the Chicago Park District: Saturday, August 17, 2019 on Columbus Dr. between Balbo and Roosevelt – Games start at 10am As of June 18, 2019 and subject to change. Please check with organizer to confirm. Auburn Gresham Who: The ARK of St. Sabina When: Tuesdays, July 2- August, 13, 5:00 - 7:00pm *Fridays, July 19 and August 23, 6:00 - 9:00pm Location(s): Tuesdays, July 2 – August 13: ARK of St. Sabina – 7800 S. Racine Ave. Fridays, July 19 and August 23: Renaissance Park - 1300 W. 79th St. Contact: Courtney Holmon or Cliff Davis ▪ [email protected] / [email protected] ▪ 773-483-4333 / 773-496-4137 ▪ www.thearkofstsabina.org Austin and Humboldt Park Who: BUILD, Inc. When: Fridays, June 28 - August 16, 2:00 – 7:00pm Location(s): June 28: BUILD, Inc. - 5100 W. Harrison St. July 12: 1640 N. Drake Ave. July 19: 4700 W. Gladys Ave. July 26: 3300 W. Le Moyne St. August 2: 4700 W. Van Buren St. August 9: 3200 W. Le Moyne St. August 16: 4700 W. Monroe St. Contact: Mark Thornton ▪ [email protected] ▪ 773-630-2912 ▪ https://www.buildchicago.org Back of the Yards Who: Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council When: Fridays, July 12 – August 16, 3:00 – 7:00pm Location(s): July 12: Sherman Park - 1301 W. 52nd St. July 19: Cornell Park - 1809 W. 50th St. July 26: Sherman Park – 1301 W. 52nd St. August 2: Kelly Park - 2725 W. 41st St. -

Obama Presidential Library the University of Chicago Adjaye Associates Contents I Urban Ii Library Iii Net-Zero Iv Design Approach in the Park Strategy Vision

OBAMA PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO ADJAYE ASSOCIATES CONTENTS I URBAN II LIBRARY III NET-ZERO IV DESIGN APPROACH IN THE PARK STRATEGY VISION OBAMA PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY │ THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO │ ADJAYE ASSOCIATES 2 I URBAN APPROACH OUR PROPOSAL RE-IMAGINES THE PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY TO BE THE FIRST TRUE URBAN LIBRARY. OPERATING ON MULTIPLE SCALES OF RENEWAL — INDIVIDUAL, URBAN, ECONOMIC, AND ECOLOGICAL — THE NEW LIBRARY ACTIVELY ENGAGES THE COMMUNITY WITH UPDATED INFRASTRUCTURE AND NEW BUSINESS OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE FUTURE GENERATIONS OF THE SOUTH SIDE OF CHICAGO. OBAMA PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY │ THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO │ ADJAYE ASSOCIATES 3 WASHINGTON PARK SOUTH SIDE OF CHICAGO WASHINGTON PARK • 7 MILES SOUTH OF THE LOOP • NEAR MIDWAY AIRPORT • HISTORICALLY SIGNIFICANT SITE • GATEWAY TO THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO • EASILY ACCESSIBLE BY PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION OBAMA PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY │ THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO │ ADJAYE ASSOCIATES 4 GARFIELD BOULEVARD HISTORICALLY OBAMA PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY │ THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO │ ADJAYE ASSOCIATES 5 GARFIELD BOULEVARD TODAY OBAMA PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY │ THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO │ ADJAYE ASSOCIATES 6 WASHINGTON PARK “LUNGS OF THE CITY” WASHINGTON PARK • CONSTRUCTED IN 1870’S • DR. JOHN RAUCH THE FOREFATHER OF THE CHICAGO PARK SYSTEM DESCRIBED IT AS “THE LUNGS OF THE CITY” • DESIGNED BY FREDERICK LAW OLMSTED & CALVERT VAUX • EARLY ATTRACTIONS TO THE PARK INCLUDED RIDING STABLES, CRICKET GROUNDS, BASEBALL FIELDS, A TOBOGGAN SLIDE, ARCHERY RANGES, A GOLF COURSE, BICYCLE PATHS, ROW BOATS, -

AMTRAK and VIA "F40PHIIS

AMTRAK and VIA "F40PHIIS VIA Class "F40PH" Nos. 6400-6419 - OMI #5897.1 Prololype phOIO AMTRAK Class "F40PH" Phase I, Nos. 200-229 - OMI #5889.1 PrOlotype pholo coll ection of louis A. Marre AMTRAK Class "F40PH" Phase II, Nos. 230-328 - OMI #5891.1 Prololype pholo collection of louis A. Marre AMTRAK Class "F40PH" Phase III, Nos. 329-400 - OM I #5893.1 Prololype pholo colleclion of lo uis A. Marre Handcrafted in brass by Ajin Precision of Korea in HO scale, fa ctory painted with lettering and lights . delivery due September 1990. PACIFIC RAIL Fro m the Hear tland t 0 th e Pacific NEWS PA(:IFIC RAllN EWS and PACIFIC N EWS are regis tered trademarks of Interurban Press, a California Corporation. PUBLISHER: Mac Sebree Railroading in the Inland Empire EDITOR: Don Gulbrandsen ART DIRECTOR: Mark Danneman A look at the variety of railroading surrounding Spokane, Wash, ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Mike Schafer ASSISTANT EDITOR: Michael E, Folk 20 Roger Ingbretsen PRODUCTION ASSISTANT: Tom Danneman CONTRIBUTING EDITOR: Elrond Lawrence 22 CPR: KINGSGATE TO KIMBERLEY EDITORIAL CONSULTANT: Dick Stephenson CONTRIBUTING ARTIST: John Signor 24 FISH LAKE, WASH, PRODUCTION MANAGER: Ray Geyer CIRCULATI ON MANAGER: Bob Schneider 26 PEND OREILLE VALLEY RAILROAD COLUMNISTS 28 CAMAS PRAIRIE AMTRAK / PASSENGER-Dick Stephenson 30 BN'S (EX-GN) HIGH LINE 655 Canyon Dr., Glendale, CA 91206 AT&SF- Elrond G, Lawrence 32 SPOKANE CITY LIMITS 908 W 25th 51.. San Bernardino, CA 92405 BURLINGTON NORTHERN-Karl Rasmussen 11449 Goldenrod St. NW, Coon Rapids, MN 55433 CANADA WEST-Doug Cummings I DEPARTMENTS I 5963 Kitchener St. -

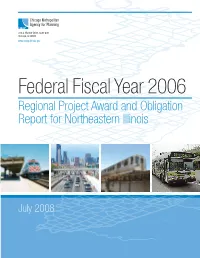

06 Report FINAL

Federal Fiscal Year 2006 Regional Project Award and Obligation Report for Northeastern Illinois July 2008 Table of Contents Introduction Section I Summary of Investments and Plan Implementation Page Table A Generalized Highway Investments by Area 4-5 Table B Expressway System Investment 6 Table C Expressway System Development 6 Table D Strategic Regional Arterial System Investment 7 Table E Transit System Development 8 Table F Pedestrian and Bikeway Facilities Investment 9 Table G Long Range Plan and Major Project Investment 10 Map 1 Transit Initiatives 11 Map 2 Roadway Construction 12 Map 3 Land Acquisition and Engineering 13 Section II Area Project Summaries for Highway Awards Summary Table of Highway Expenditures 14 Cook County Chicago 15-16 North Shore 17 Northwest 18 North Central 19 Central 20 Southwest 21-22 South 23-24 Du Page County 25-26 Kane County 27 Kendall County 28 Lake County 29 Mc Henry County 30 Will County 31-32 Congestion Mitigation / Air Quality (CMAQ) - FTA Transfers 33 Regional Areawide Projects 34-35 Operation Green Light / Rail Crossing Improvements 36 Grade Crossing Protection Fund (GCPF) 36 Economic Development Program/ Truck Route 37 Section III RTA Service Board Project Summaries for Transit Grants Summary Table of Transit Expenditures 38 Pace - Suburban Bus Board 39 CTA - Chicago Transit Authority 40-41 Metra - Northeastern Illinois Rail Corporation 42-45 JARC (Job Access - Reverse Commute) 46 Summary Table of Service Board Grants 46 Appendix I State Funding for Local Projects 47-48 Appendix II Illinois State Toll Highway Authority Project Awards 49 Appendix III Northeastern Illinois Investments in Bikeways and Pedestrian Facilities 50 Table - A Generalized Highway Investment by Area ( All costs are in total dollars ) Illinois DOT Project Awards Project Type C/L Mi. -

220 East Illinois Street Prime Retail and Office Location Opportunities 220 East Illinois Street

PRIME RETAIL AND OFFICE OPPORTUNITIES 220 EAST ILLINOIS STREET PRIME RETAIL AND OFFICE LOCATION OPPORTUNITIES 220 EAST ILLINOIS STREET Situated at the Southern end of the Magnificent Mile shopping district in the booming Streeterville neighborhood, Optima Signature is uniquely positioned to capture the attention of a broad and varied group of shoppers, residents, tourists and office workers frequenting this diverse and vibrant THE MAGNIFICENT MILE trade area. The Magnificent Mile, immediately to the West of Optima Signature, stretches from Oak Street to the Chicago River and is one of the world’s most successful retail and office environments with over 3.3 million square feet of retail and over 450 shops; it generates $1.9 billion in annual sales. 220 East Illinois Street Nearby a new Whole Foods and a 16 screen AMC Theater, Optima Signature is also on the main route to Navy Pier, the Midwest’s busiest To Navy Pier tourist attraction. It’s also centrally located in Streeterville, a vibrant and Grand Avenue densely populated residential and office area with multiple new high end residential towers under construction. This 56-story building has 490 apartments complimented by Optima Illinois Street Chicago Center next door with 325 units on 42 floors. Between these two buildings there will be 815 units occupied by an affluent customer base. By the numbers: Cityfront Plaza ■ 45,000: average daily pedestrians on the Mag Mile ■ 42,000: average daily vehicles on the Mag Mile ■ 1.2 million: number of attendees at the Mag Mile Lights Festival, -

A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Motor Row, Chicago, Illinois Street

NFS Form 10-900-b OMR..Np. 1024-0018 (March 1992) / ~^"~^--.~.. United States Department of the Interior National Park Service / / v*jf f ft , I I / / National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form /..//^' -A o C_>- f * f / *•• This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. x New Submission Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Motor Row, Chicago, Illinois B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) Dealerships and the Development of a Commercial District 1905-1936 Evolution of a Building Type 1905-1936 Motor Row and Chicago Architects 1905-1936 C. Form Prepared by name/title _____Linda Peters. Architectural Historian______________________ street & number 435 8. Cleveland Avenue telephone 847.506.0754 city or town ___Arlington Heights________________state IL zip code 60005 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation.