Changes in Hutterite House Types

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alberta the Co-Founders of Ribstone Creek Brewery Have Brought a Value-Added Business Back to the Village Where They Grew Up

Fighting Fires Jerusalem OUT HERE, when the artichoke has HOMECOMING HAS A water is Frozen Feed and bioFuel DIFFERENT potential MEANING. » PAGE 13 » PAGE 23 Livestock checklist now available in-store and at UFA.com. Publications Mail Agreement # 40069240 110201353_BTH_Earlug_AFE_v1.indd 1 2013-09-16 4:46 PM Client: UFA . Desiree File Name: BTH_Earlug_AFE_v1 Project Name: BTH Campaign CMYK PMS ART DIR CREATIVE CLIENT MAC ARTIST V1 Docket Number: 110201353 . 09/16/13 STUDIO Trim size: 3.08” x 1.83” PMS PMS COPYWRITER ACCT MGR SPELLCHECK PROD MGR PROOF # Volume 10, number 23 n o V e m b e r 1 1 , 2 0 1 3 Farmer brews up big business in rural Alberta The co-founders of Ribstone Creek Brewery have brought a value-added business back to the village where they grew up the recently completed ribstone Creek brewery still has plenty of room to expand brewing capacity. Photo: Jennifer Blair Vice-president Chris fraser had “they basically said to him, ‘You to expand once to meet growing By Jennifer Blair seen some craft breweries along really don’t know what you’re demand for its lager. af staff / edgerton his travels, and as soon as he sug- doing, do you?’ and we had to “It was a nice problem to have, “Nothing quite gets gested it, the four co-founders — admit that we didn’t,” Paré said. when your demand outweighs on Paré’s plan to build Paré, fraser, Ceo Cal Hawkes, and the supplier put the group your production,” said Paré. “But people’s attention like a brewery in the heart of Cfo alvin gordon — knew they in touch with brewmaster and unfortunately, it does hurt you, when you say the word D rural alberta came about had hit upon the right idea. -

Corporate Registry Registrar's Periodical

Service Alberta ____________________ Corporate Registry ____________________ Registrar’s Periodical SERVICE ALBERTA Corporate Registrations, Incorporations, and Continuations (Business Corporations Act, Cemetery Companies Act, Companies Act, Cooperatives Act, Credit Union Act, Loan and Trust Corporations Act, Religious Societies’ Land Act, Rural Utilities Act, Societies Act, Partnership Act) 0767527 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps 1209706 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps Registered 2019 NOV 01 Registered Address: 300- Registered 2019 NOV 07 Registered Address: SUITE 10711 102 ST NW , EDMONTON ALBERTA, 230, 2323 32 AVE NE, CALGARY ALBERTA, T5H2T8. No: 2122266683. T2E6Z3. No: 2122278068. 0995087 B.C. INC. Other Prov/Territory Corps 1221996 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps Registered 2019 NOV 14 Registered Address: 10012 - Registered 2019 NOV 04 Registered Address: 3400, 350 101 STREET, PO BOX 6210, PEACE RIVER - 7TH AVENUE SW, CALGARY ALBERTA, T2P3N9. ALBERTA, T8S1S2. No: 2122287010. No: 2122268044. 10191787 CANADA INC. Federal Corporation 1221998 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps Registered 2019 NOV 13 Registered Address: 4300 Registered 2019 NOV 04 Registered Address: 3400, 350 BANKERS HALL WEST, 888 - 3RD STREET S.W., - 7TH AVENUE SW, CALGARY ALBERTA, T2P3N9. CALGARY ALBERTA, T2P 5C5. No: 2122287101. No: 2122268176. 102089241 SASKATCHEWAN LTD. Other 1221999 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps Prov/Territory Corps Registered 2019 NOV 04 Registered 2019 NOV 04 Registered Address: 3400, 350 Registered Address: 101 - 1ST ST. EAST P.O. BOX - 7TH AVENUE SW, CALGARY ALBERTA, T2P3N9. 210, DEWBERRY ALBERTA, T0B 1G0. No: No: 2122268259. 2122270461. 1222024 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps 10632449 CANADA LTD. Federal Corporation Registered 2019 NOV 04 Registered Address: 3400, 350 Registered 2019 NOV 04 Registered Address: 855 - 2 - 7TH AVENUE SW, CALGARY ALBERTA, T2P3N9. -

Hotspot You Would Like to Visit Within Beaver County Daysland Property

Cooking Lake-Blackfoot Provincial Recreation Area Parkland Natural Area For Tips and Etiquette Francis Viewpoint of Nature Viewing Click “i” Above Tofield Nature Center Beaverhill Bird Observatory Ministik Lake Game Bird Sanctuary Earth Academy Park Viking Bluebird Trails Black Nugget Lake Park Click on the symbol of the Camp Lake Park nature hotspot you would like to visit within Beaver County Daysland Property Viking Ribstones Prepared by Dr. Glynnis Hood, Dr. Glen Hvenegaard, Dr. Anne McIntosh, Wyatt Beach, Emily Grose, and Jordan Nakonechny in partnership with the University of Alberta All photos property of Jordan Nakonechny unless otherwise stated Augustana Campus and the County of Beaver Return to map Beaverhill Bird Observatory The Beaverhill Bird Observatory was established in 1984 and is the second oldest observatory for migration monitoring in Canada. The observatory possesses long-term datasets for the purpose of analyzing population trends, migration routes, breeding success, and survivorship of avian species. The observatory is located on the edge of Beaverhill Lake, which was designated as a RASMAR in 1987. Beaverhill Lake has been recognized as an Important Bird Area with the site boasting over 270 species, 145 which breed locally. Just a short walk from the laboratory one can commonly see or hear white-tailed deer, tree swallows, yellow warblers, house wrens, yellow-headed blackbirds, red- winged blackbirds, sora rails, and plains garter snakes. For more information and directions visit: http://beaverhillbirds.com/ Return to map Black Nugget Lake Park Black Nugget Lake Park contains a campground of well-treed sites surrounding a human-made lake created from an old coal mine. -

AMENDMENT 002 Attn: Sìne Macadam GETS Reference No

Title – Sujet RETURN BIDS TO: Cemetery Maintenance for Alberta RETOURNER LES SOUMISSIONS À: Solicitation No. – N° de l’invitation Date Veterans Affairs Canada 3000726188 2021-06-17 Procurement & Contracting – AMENDMENT 002 Attn: Sìne MacAdam GETS Reference No. – N° de reference de SEAG [email protected] - File No. – N° de dossier CCC No. / N° CCC - FMS No. / N° VME Time Zone AMENDMENT - REQUEST FOR Fuseau horaire Solicitation Closes – L’invitation prend fin Atlantic Daylight PROPOSAL at – à 2:00 PM Time on – le 2021-06-29 ADT MODIFICATION - DEMANDE DE F.O.B. - F.A.B. PROPOSITION Plant-Usine: Destination: Other-Autre: Address Inquiries to : - Adresser toutes questions Buyer Id – Id de l’acheteur à: Sìne MacAdam Proposal To: Veterans Affairs Canada Telephone No. – N° de téléphone : FAX No. – N° de FAX (902) 626-5288 N/A We hereby offer to sell to Her Majesty the Queen in Destination – of Goods, Services, and Construction: right of Canada, in accordance with the terms and Destination – des biens, services et construction : conditions set out herein, referred to herein or See Herein attached hereto, the goods, services, and construction listed herein and on any attached sheets at the price(s) set out thereof. Proposition aux: Anciens Combattants Canada Nous offrons par la présente de vendre à Sa Majesté la Reine du chef du Canada, aux conditions énoncées ou incluses par référence dans la présente et aux annexes ci-jointes, les biens, services et construction énumérés ici sur toute feuille ci-annexées, au(x) prix indiqué(s) Instructions: See Herein Instructions : Voir aux présentes Delivery required - Delivered Offered – Livraison proposée Comments - Commentaires Livraison exigée See Herein Vendor/firm Name and address This requirement contains a security requirement Raison sociale et adresse du fournisseur/de l’entrepreneur Vendor/Firm Name and address Raison sociale et adresse du fournisseur/de l’entrepreneur Facsimile No. -

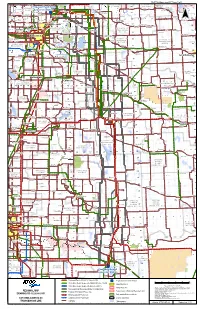

St2 St9 St1 St3 St2

! SUPP2-Attachment 07 Page 1 of 8 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! .! ! ! ! ! ! SM O K Y L A K E C O U N T Y O F ! Redwater ! Busby Legal 9L960/9L961 57 ! 57! LAMONT 57 Elk Point 57 ! COUNTY ST . P A U L Proposed! Heathfield ! ! Lindbergh ! Lafond .! 56 STURGEON! ! COUNTY N O . 1 9 .! ! .! Alcomdale ! ! Andrew ! Riverview ! Converter Station ! . ! COUNTY ! .! . ! Whitford Mearns 942L/943L ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 56 ! 56 Bon Accord ! Sandy .! Willingdon ! 29 ! ! ! ! .! Wostok ST Beach ! 56 ! ! ! ! .!Star St. Michael ! ! Morinville ! ! ! Gibbons ! ! ! ! ! Brosseau ! ! ! Bruderheim ! . Sunrise ! ! .! .! ! ! Heinsburg ! ! Duvernay ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! 18 3 Beach .! Riviere Qui .! ! ! 4 2 Cardiff ! 7 6 5 55 L ! .! 55 9 8 ! ! 11 Barre 7 ! 12 55 .! 27 25 2423 22 ! 15 14 13 9 ! 21 55 19 17 16 ! Tulliby¯ Lake ! ! ! .! .! 9 ! ! ! Hairy Hill ! Carbondale !! Pine Sands / !! ! 44 ! ! L ! ! ! 2 Lamont Krakow ! Two Hills ST ! ! Namao 4 ! .Fort! ! ! .! 9 ! ! .! 37 ! ! . ! Josephburg ! Calahoo ST ! Musidora ! ! .! 54 ! ! ! 2 ! ST Saskatchewan! Chipman Morecambe Myrnam ! 54 54 Villeneuve ! 54 .! .! ! .! 45 ! .! ! ! ! ! ! ST ! ! I.D. Beauvallon Derwent ! ! ! ! ! ! ! STRATHCONA ! ! !! .! C O U N T Y O F ! 15 Hilliard ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! N O . 1 3 St. Albert! ! ST !! Spruce ! ! ! ! ! !! !! COUNTY ! TW O HI L L S 53 ! 45 Dewberry ! ! Mundare ST ! (ELK ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! . ! ! Clandonald ! ! N O . 2 1 53 ! Grove !53! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ISLAND) ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Ardrossan -

Published Local Histories

ALBERTA HISTORIES Published Local Histories assembled by the Friends of Geographical Names Society as part of a Local History Mapping Project (in 1995) May 1999 ALBERTA LOCAL HISTORIES Alphabetical Listing of Local Histories by Book Title 100 Years Between the Rivers: A History of Glenwood, includes: Acme, Ardlebank, Bancroft, Berkeley, Hartley & Standoff — May Archibald, Helen Bircham, Davis, Delft, Gobert, Greenacres, Kia Ora, Leavitt, and Brenda Ferris, e , published by: Lilydale, Lorne, Selkirk, Simcoe, Sterlingville, Glenwood Historical Society [1984] FGN#587, Acres and Empires: A History of the Municipal District of CPL-F, PAA-T Rocky View No. 44 — Tracey Read , published by: includes: Glenwood, Hartley, Hillspring, Lone Municipal District of Rocky View No. 44 [1989] Rock, Mountain View, Wood, FGN#394, CPL-T, PAA-T 49ers [The], Stories of the Early Settlers — Margaret V. includes: Airdrie, Balzac, Beiseker, Bottrell, Bragg Green , published by: Thomasville Community Club Creek, Chestermere Lake, Cochrane, Conrich, [1967] FGN#225, CPL-F, PAA-T Crossfield, Dalemead, Dalroy, Delacour, Glenbow, includes: Kinella, Kinnaird, Thomasville, Indus, Irricana, Kathyrn, Keoma, Langdon, Madden, 50 Golden Years— Bonnyville, Alta — Bonnyville Mitford, Sampsontown, Shepard, Tribune , published by: Bonnyville Tribune [1957] Across the Smoky — Winnie Moore & Fran Moore, ed. , FGN#102, CPL-F, PAA-T published by: Debolt & District Pioneer Museum includes: Bonnyville, Moose Lake, Onion Lake, Society [1978] FGN#10, CPL-T, PAA-T 60 Years: Hilda’s Heritage, -

Updated Population of Places on the Alberta Road Map with Less Than 50 People

Updated Population of Places on the Alberta Road Map with less than 50 People Place Population Place Population Abee 25 Huallen 28 Altario 26 Hylo 22 Ardenode 0 Iddesleigh 14 Armena 35 Imperial Mills 19 Atikameg 22 Indian Cabins 11 Atmore 37 Kapasiwin 14 Beauvallon 7 Kathryn 29 Beaver Crossing 18 Kavanagh 41 Beaverdam 15 Kelsey 10 Bindloss 14 Keoma 40 Birch Cove 19 Kirkcaldy 24 Bloomsbury 18 Kirriemuir 28 Bodo 26 La Corey 40 Brant 46 Lafond 36 Breynat 22 Lake Isle 26 Brownfield 27 Larkspur 21 Buford 47 Leavitt 48 Burmis 32 Lindale 26 Byemoor 40 Lindbrook 18 Carcajou 17 Little Smoky 28 Carvel 37 Lyalta 21 Caslan 23 MacKay 15 Cessford 31 Madden 36 Chinook 38 Manola 29 Chisholm 20 Mariana Lake 8 Compeer 21 Marten Beach 38 Conrich 19 McLaughlin 41 Cynthia 37 Meeting Creek 42 Dalemead 32 Michichi 42 Dapp 27 Millarville 43 De Winton 44 Mission Beach 37 Deadwood 22 Mossleigh 47 Del Bonita 20 Musidora 13 Dorothy 14 Nestow 10 Duvernay 26 Nevis 30 Ellscott 10 New Bridgden 24 Endiang 35 New Dayton 47 Ensign 17 Nisku 40 Falun 25 Nojack 19 Fitzgerald 4 North Star 49 Flatbush 30 Notekiwin 17 Fleet 28 Onefour 31 Gadsby 40 Opal 13 Gem 24 Orion 11 Genesee 18 Peace Point 21 Glenevis 25 Peoria 12 Goodfare 11 Perryvale 20 Hairy Hill 46 Pincher 35 Heath 14 Pocahontas 10 Hilliard 35 Poe 15 Hoadley 9 Purple Springs 26 Hobbema 35 Queenstown 15 Page 1 of 2 Updated Population of Places on the Alberta Road Map with less than 50 People Rainier1 29 Star 32 Raven 12 Steen River 12 Red Willow 40 Streamstown 15 Reno 20 Sundance Beach 37 Ribstone 48 Sunnynook 13 Rich Valley 32 Tangent 39 Richdale 14 Tawatinaw 10 Rivercourse 14 Telfordville 28 Rowley 11 Tulliby Lake 18 St. -

Advances in Hutterian Scholarship

Journal of Amish and Plain Anabaptist Studies Volume 3 Issue 1 Special section: Education Article 8 2015 Advances in Hutterian Scholarship William L. Smith Follow this and additional works at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/amishstudies Part of the Anthropology Commons Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Recommended Citation Smith, William L. 2015. "Advances in Hutterian Scholarship." Journal of Amish and Plain Anabaptist Studies 3(1):124-29. This Review Essay is brought to you for free and open access by IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The University of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Amish and Plain Anabaptist Studies by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Review Essay Advances in Hutterian Scholarship Review of: Janzen, Rod, and Max Stanton. 2010. The Hutterites in North America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. Review of: Katz, Yossi, and John Lehr. 2014[2012] Inside the Ark: The Hutterites in Canada and the United States [2nd ed.]. Regina, SK: University of Regina Press. By William L. Smith, Sociology, Georgia Southern University Certain elements of Hutterite life have changed significantly since the publication of Hutterian Brethren: The Agricultural Economy and Social Organization of a Communal People by John W. Bennett, Hutterite Society by John A. Hostetler, The Dynamics of Hutterite Society by Karl A. Peter, and The Hutterites in North America by John Hostetler and Gertrude Enders Huntington. -

Hutterite Colonies in Montana Map

Hutterite colonies in montana map Continue Three groups of Hutterites are located exclusively in the breadbasket or prairies of North America. Hutterites have subsisted almost entirely on agriculture since migrating to North America in 1874 which helps explain their geographical locations. All of Schmideleut's colonies are located in central North America, mainly in Manitoba and South Dakota. There are several colonies in North Dakota and Minnesota. Darius and Lehrer-leut are located in western North America, mainly in Saskatchewan, Alberta and Montana with spraying colonies in British Columbia, Washington and Oregon. Most colonies are located in Alberta (168), followed by Manitoba (107), Saskatchewan (60) and South Dakota (54). MB SK AB AB BC MT WA ND SD MN Totals Schmiedeleut 107 6 54 9 177 Dariusleut 29 98 2 15 5 1 149 Lehrerleut 1 31 69 35 135 Totals 107 60 168 2 50 5 5 54 9 462 A total of 462 colonies are scattered across the plains of North America. The total number of hutterites in NA hovers around 45,000. Approximately 75% of all Hutterites live in Canada, and the remaining 25% in the United States. The map below shows the distribution of Hutterite colonies in North America. Ethno-religious group since the 16th century; The community branch of the anabaptists HutteritesHutterite women at workTotal population50,000 (2020)FounderJacob HutterReligionsAnabaptistScripturesThe BibleLanguagesHutterite German, standard German, English Part of the series onAnabaptismDirk Willems (pictured) saves its pursuer. This act of mercy led to his -

Alberta Archaeological Review

ALBERTA ARCHAEOLOGICAL REVIEW Number 23 ISSN 0701-1776 Fall 1991 Copyright © 1992 by the publisher, The Archaeological Society of Alberta _—,— ';; i •i.-V^.'; • 7 -:,.v:. it •:;">'• .' JlSlI^ ;ifj! ••Hi HHHHI •E IH^H^HII^HHI <•! >••:; • ' . • £i Inside: • Annual Meeting Report Ghost River Dam Area page 3 page 8 Conference Reports A Roman Lamp in Alberta page 12 page 16 Archaeological Society of Alberta Charter #8205, registered under the Societies Act of Alberta on February 7. 1975 PROVINCIAL SOCIETY OFFICERS FOR 1991-92 Lethbridge Centre: President: Barry Wood (elected April 1991) General Delivery Cardston, Alberta President: Dr. Brian O.K. Reeves T0K 0L0 #16, 2200 Varsity Estates Dr. N.W. 653-2461 Calgary, Alberta T3B 4Z8 (403) 286-8079 Rep.: Lawrence Halmrast P. O. Box 1656 Executive Secretary/ Mrs. Jeanne Cody Warner, Alberta T0H 2L0 Treasurer: 1202 Lansdowne Avenue S.W. 642-2126 Calgary, Alberta T2S 1A6 (403) 243-4340 South Eastern President: Daryl Heron Alberta 349 Cameron Road S. E. Editors, Review & Dr. Michael C. Wilson Archaeological Medicine Hat, Alberta TIB 2B8 Publications: Department of Geography Society 529-6117 University of Lethbridge 4401 University Drive Rep.: Jim Marshall Lethbridge, Alberta T1K 3M4 97-1st. Street N. E. (403) 329-2225 Medicine Hat, Alberta T1A 5J9 527-2774 Past President: John H. Brumley Group Box 20, Veinerville, Alberta Underwater President: Gordon Ross Medicine Hat, Alberta T1A 7E5 Archaeology Society: 8754-97 Avenue (403) 526-6021 Edmonton, Alberta T6C 2C1 465-5156 Vice-President: (position not filled) Peace River President: Morris Burroughs Elected Secretary: Beth (Mrs. E.A.) Macintosh Archaeological 9205-111 Avenue #314, 4516 Valiant Drive N.W. -

The Hutterites in Canada and the United States by Yossi Katz and John Lehr Rod Janzen Fresno Pacific Nu Iversity

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for Fall 2013 Review of Inside the Ark: The Hutterites in Canada and the United States by Yossi Katz and John Lehr Rod Janzen Fresno Pacific nU iversity Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the American Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, and the United States History Commons Janzen, Rod, "Review of Inside the Ark: The Hutterites in Canada and the United States by Yossi Katz and John Lehr" (2013). Great Plains Quarterly. 2563. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/2563 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 258 GREAT PLAINS QUARTERLY, FALL 2013 and 2009. But this is also problematic, limiting what can be said about Hutterite history and the diversity of beliefs and practices across the North American Hutterite community. In the short his torical section, for example, the Hutterites are described as "Christian perfectionists," which is somewhat confusing since the word "perfection ism" usually implies Christian theological under standings not associated with the Hutterites. Even more disconcerting is the fact that the book is not really a general study of all branches of the contemporary Hutterite community. Of the 50,000-plus Hutterites in North America, for example, nearly two-thirds are members of the of ten more conservative Lehrerleut and Dariusleut Inside the Ark: The Hutterites in Canada and the branches (whose colonies are located primarily United States. -

In the Supreme Court of the United States ______

No. _______ In the Supreme Court of the United States __________ BIG SKY COLONY, INC., AND DANIEL E. WIPF, PETITIONERS v. MONTANA DEPARTMENT OF LABOR AND INDUSTRY __________ ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF MONTANA __________ PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI __________ DOUGLAS LAYCOCK S. KYLE DUNCAN University of Virginia LUKE W. GOODRICH School of Law Counsel of Record 580 Massie Road ERIC C. RASSBACH Charlottesville, VA 22903 HANNAH C. SMITH JOSHUA D. HAWLEY RON A. NELSON DANIEL BLOMBERG MICHAEL P. TALIA The Becket Fund for Church, Harris, Religious Liberty Johnson & Williams 3000 K St., NW Ste. 220 114 3rd Street South Washington, DC 20007 Great Falls, MT 59403 (202) 955-0095 [email protected] Counsel for Petitioner QUESTIONS PRESENTED 1. Whether the Free Exercise Clause requires a plaintiff to demonstrate that the challenged law sin- gles out religious conduct or has a discriminatory mo- tive, as the First, Second, Fourth, and Eighth Cir- cuits and Montana Supreme Court have held, or whether it is instead sufficient to demonstrate that the challenged law treats a substantial category of nonreligious conduct more favorably than religious conduct, as the Third, Sixth, Tenth, and Eleventh Circuits and Iowa Supreme Court have held. 2. Whether the government regulates “an internal church decision” in violation of the Free Exercise Clause, Hosanna-Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church & School v. EEOC, 132 S. Ct. 694 (2012), when it forces a religious community to provide workers’ compensation insurance to its members in violation of the internal rules governing the commu- nity and its members.