Daf Ditty Yoma 73: “Inuy”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rabbi Norman Lamm Terumah the Jewish Center March 2, 1968

RABBI NORMAN LAMM TERUMAH THE JEWISH CENTER MARCH 2, 1968 "LIVING UP TO YOUR IMAGE" We read in this morning's Sidra of the instructions given to Moses to build the Tabernacle. Amongst other things, he is commanded to build the Ark, containing the Tablets of the Law. This aron, Moses is told, should be made of wood overlaid with zahav tahor, pure gold, both on the inside and the outside of the Ark: mi-bayit u-mi-hutz tetzapenu. Our Rabbis (Yoma 72b) found in this apparently mundane law, a principle of great moral significance. Rava said: from this we learn that kol talmid bakham she^in tokho ke'varo eino talmid bakham, a scholar whose inner life does not correspond to his outer appearances is not an authentic scholar. The Ark or aron, as the repository of the Tablets of the Law, is a symbol of a talmid bakham, a student of the Law. The zahav tahor, pure gold, repre- sents the purity of character. And the requirement that this gold be placed mi-bayit u-mi-hutz, both within and without the Ark, in- dicates the principle that a true scholar must live in such a manner that he always be tokho keTvaro, alike inwardly and outwardly. Thus, our Rabbis saw in our verse a plea for integrity of character, a warning against a cleavage between theory and practice, against a discontinuity between inwardness and outwardness, against a clash between inner reality and outer appearance. A real Jew must always be tokho keTvaro. -2- Now that sounds like a truism; but it is nothing of the sort. -

Yoma Book.Indb

Perek V Daf 56 Amud a BACKGROUND ten log that I will later separate shall be the fi rst tithe;N and another ֲﬠ ָׂשָרה ַמ ֲﬠ ֵׂשר ִר ׁאשוֹן, ִּת ׁ ְש ָﬠה ַמ ֲﬠ ֵׂשר Terumot and tithes : ְּת ּרומוֹת ּו ַמ ַﬠ ְׂשרוֹת – tenth from the rest, which equals nine log of the remaining ninety, Terumot and tithes are separated in the following manner. For example, if one ׁ ֵש ִני, ּו ֵמ ֵיחל ְו ׁש ֶוֹתה ִמ ָיּד, ִ ּד ְבֵרי ַר ִּבי -shall be second tithe. And he redeems the second tithe with money has one hundred units of food or beverage, he first re ֵמ ִאיר. that he will later take to Jerusalem, and he may then immediately moves the teruma gedola, which is given to the priests. The N drink the wine. Aft er Shabbat, when he removes portions from the average amount of this gift is one-fiftieth of the produce, mixture and places them in vessels, they are retroactively designated which in this example is two units. Next, the first tithe is B as terumot and tithes. Th is is the statement of Rabbi Meir. removed and given to a Levite. This gift is ten percent of the remaining produce, or slightly less than ten units in this case. In most years, another tenth is taken from the rest as second tithe, which is taken to Jerusalem and consumed there. Here the second tithe amounts to slightly more than nine units. In years three and six of the Sabbatical cycle, this tithe is given to the poor instead. -

What Sugyot Should an Educated Jew Know?

What Sugyot Should An Educated Jew Know? Jon A. Levisohn Updated: May, 2009 What are the Talmudic sugyot (topics or discussions) that every educated Jew ought to know, the most famous or significant Talmudic discussions? Beginning in the fall of 2008, about 25 responses to this question were collected: some formal Top Ten lists, many informal nominations, and some recommendations for further reading. Setting aside the recommendations for further reading, 82 sugyot were mentioned, with (only!) 16 of them duplicates, leaving 66 distinct nominated sugyot. This is hardly a Top Ten list; while twelve sugyot received multiple nominations, the methodology does not generate any confidence in a differentiation between these and the others. And the criteria clearly range widely, with the result that the nominees include both aggadic and halakhic sugyot, and sugyot chosen for their theological and ideological significance, their contemporary practical significance, or their centrality in discussions among commentators. Or in some cases, perhaps simply their idiosyncrasy. Presumably because of the way the question was framed, they are all sugyot in the Babylonian Talmud (although one response did point to texts in Sefer ha-Aggadah). Furthermore, the framing of the question tended to generate sugyot in the sense of specific texts, rather than sugyot in the sense of centrally important rabbinic concepts; in cases of the latter, the cited text is sometimes the locus classicus but sometimes just one of many. Consider, for example, mitzvot aseh she-ha-zeman gerama (time-bound positive mitzvoth, no. 38). The resulting list is quite obviously the product of a committee, via a process of addition without subtraction or prioritization. -

Pikuach Nefesh -- Saving a Life

Wed 6 May 2020 / 12 Iyar 5780 B”H Dr Maurice M. Mizrahi Congregation Adat Reyim Adult Education Pikuach Nefesh -- Saving a Life Introduction Judaism enjoins us to save lives. The Torah says: You shall not stand idly by the blood of your neighbor. [Leviticus 19:16] and ּושְׁמַרְׁתֶֶּ֤םאֶת־חֻקֹּתַי֙ וְׁאֶ ת־מִשְׁ פָּטַַ֔ יאֲשֶֶׁ֨ ר יַעֲשֶ ֶׂ֥ ה אֹּתָּ ָ֛ם הָּאָּדָּ ָ֖ם וָּחַ ַ֣י בָּהֶ ֶ֑םאֲנִ ָ֖ייְׁהוָָּֽה You shall therefore keep my statutes and my ordinances, which, if a man performs, he shall live by them. I am the Lord. [Leviticus 18:5] These words were echoed much later by the prophet Ezekiel. [Ezekiel 20:11] The Talmud derives from the verse “you shall live by them” that Jews must live by the Torah and not die because of it. This is the doctrine of Pikuach regard for human life. Even if you must break -- (פִ קּוחַ נֶפש) Nefesh commandments to save a life (yours or another's), do so. Alternate Talmudic logic: The objective is to maximize observance of commandments. Allowing someone to live increases the number of commandments observed. Example: Violating Shabbat to save someone allows him to observe other Shabbatot in the future. [Yoma 85b, Shabbat 151b] Mishna: If uncertain whether life is truly in danger, err on the side of assuming it is. [Yoma 8:6] If turns out there was no threat to human life, no sin and no reason to feel guilty. How far can you go? The Talmud says that healing is prohibited on Shabbat because you need to crush herbs to make medicine, and crushing is prohibited on Shabbat. -

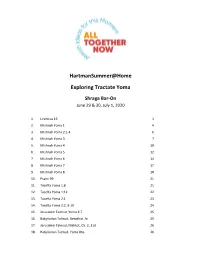

Hartmansummer@Home Exploring Tractate Yoma

HartmanSummer@Home Exploring Tractate Yoma Shraga Bar-On June 29 & 30, July 1, 2020 1. Leviticus 16 1 2. Mishnah Yoma 1 4 3. Mishnah Yoma 2:1-4 6 4. Mishnah Yoma 3 7 5. Mishnah Yoma 4 10 6. Mishnah Yoma 5 12 7. Mishnah Yoma 6 14 8. Mishnah Yoma 7 17 9. Mishnah Yoma 8 18 10. Psalm 99 21 11. Tosefta Yoma 1:8 21 12. Tosefta Yoma 1:12 22 13. Tosefta Yoma 2:1 23 14. Tosefta Yoma 2:2, 9-10 24 15. Jerusalem Talmud, Yoma 3:7 25 16. Babylonian Talmud, Berakhot 7a 25 17. Jerusalem Talmud, Makkot, Ch. 2, 31d 26 18. Babylonian Talmud, Yoma 86a 26 The Shalom Hartman Institute is a leading center of Jewish thought and education, serving Israel and North America. Our mission is to strengthen Jewish peoplehood, identity, and pluralism; to enhance the Jewish and democratic character of Israel; and to ensure that Judaism is a compelling force for good in the 21st century. Share what you’re learning this summer! #hartmansummer @SHI_america shalomhartmaninstitute hartmaninstitute 475 Riverside Dr., Suite 1450 New York, NY 10115 212-268-0300 [email protected] | shalomhartman.org 1. Leviticus 16 )א( ַוְיַדֵּבר ה' ֶאל ֹמֶשה ַאֲחֵּרי מֹות ְשֵּני ְבֵּני ַאֲהֹרן ְבָקְרָבָתם ִלְפֵּני ה' ַוָיֻמתּו: )ב( ַויֹאֶמר ה' ֶאל ֹמֶשה ַדֵּבר ֶאל ַאֲהֹרן ָאִחיָך ְוַאל ָיבֹא ְבָכל ֵּעת ֶאל ַהֹקֶדש ִמֵּבית ַלָפֹרֶכת ֶאל ְפֵּני ַהַכֹפֶרת ֲאֶשר ַעלָ הָאֹרןְ ולֹאָ ימּות ִכי ֶבָעָנן ֵּאָרֶאה ַעלַהַכֹפֶרת: )ג( ְבזֹאתָיבֹא ַאֲהֹרן ֶאלַהֹקֶדש ְבַפר ֶבן ָבָקר ְלַחָטאת ְוַאִיל ְלֹעָלה: )ד( ְכֹתֶנת ַבד ֹקֶדש ִיְלָבש ּוִמְכְנֵּסי ַבד ִיְהיּו ַעל ְבָשרֹו ּוְבַאְבֵּנט ַבד ַיְחֹגר ּוְבִמְצֶנֶפת -

JUDGE RIGHTEOUSLY; PURSUE JUSTICE Exodus 23:1-3, 6; Leviticus 19:15, 24:22; Deuteronomy 1:16-17; 16:19-20

THE ETHICAL TORAH: THE SAGES SPEAK No. 23-B (Second of Two Parts) in series JUDGE RIGHTEOUSLY; PURSUE JUSTICE Exodus 23:1-3, 6; Leviticus 19:15, 24:22; Deuteronomy 1:16-17; 16:19-20 Excerpts from the mussaria.org website, a compilation of Jewish ethical commentaries throughout the ages Compiled by Rabbi Arthur J. Levine, Ph.D., J.D. 2 TITLES IN THIS SERIES 1A/B The Golden Verse: Love Your Neighbor (Leviticus 19:18) 2 Imagining Man: In Our Image (Genesis 1:26-28) 3 Open Your Hand (Deuteronomy 15:7-11) 4 Talebearer/Standing Idly By (Leviticus 19:16) 5 Sin Crouches at the Door (Genesis 4:6-10) 6 Hear, O Israel (Deuteronomy 6:5-7) 7 Rebuke Thy Neighbour (Leviticus 19:17) 8 Keep Far from Falsehood (Exodus 23:1,2,7) 9 Do Not Follow Your Heart; You Shall Not Covet (Numbers 15:39, Ex. 20:14; Deut. 5:18) 10 Honoring Parents (Exodus 20:12/Leviticus 19:3/Deuteronomy 5:16) 11 Keep the Way of the Lord (Genesis 18:19) 12 Stumbling-Block Before the Blind (Leviticus 19:14) 13 Not Good to Be Alone; They Shall Be One Flesh (Genesis 2:18, 2:22-24) 14 Love the Stranger (Exodus 22:20-23/Deuteronomy 10:18-19) 15 Whosoever Sheddeth Man’s Blood (Genesis 9:5-6) 16 Return Your Enemy’s Ox; Help Him Unburden It (Exodus 23:4-5, Deuteronomy 22:1-4) 17 Will Not the Judge of the World Do Justly? (Exodus 18:23-27, 32-33) 18 Set Apart; Choose Life (Leviticus 18:3-5, 20:24-26; Deuteronomy 30:19-20) 19 The Imagination of Man’s Heart Is Evil (Genesis 6:5, 8:21) 20 Do Not Wrong Your Neighbor (Leviticus 19:13; 25:14, 17) 21 You Shall Be Holy (Ex. -

Yoma 044.Pub

י"ד סיון תשפ“אTues, May 25 2021 OVERVIEW of the Daf Distinctive INSIGHT 1) The prohibition against being in the sanctuary when Ketores atones for lashon hara יבא דבר שבחשאי ויכפר על מעשה חשאי the incense is burning A Baraisa explains the verse that teaches the prohibition against being in the Sanctuary when the incense is burning. T he ketores had the power to atone for lashon hara, for Rava explains how we know the verse refers to the time both are done quietly. Why is ketores considered to be a the incense is burning. quiet activity? Rashi (Arachim 16a) explains that the ketores which is a private place, away from , היכל Rava’s assertion that the incense effects atonement is is brought in the היכל unsuccessfully challenged. public view. In fact, no one was allowed to be in the A Mishnah rules that one is not allowed to be in the together with the kohen at the moment the ketores was area between the Ulam and the Altar while the incense is brought. Tosafos HaRosh proposes that perhaps the sprin- burning. kling of the blood of the bull of Yom Kippur should also be R’ Elazar explains that the Mishnah’s ruling applies only considered a private and quiet action, which should atone He . היכל when the incense is burned in the Sanctuary but not when for lashon hara, for it, too, was done in the it is burning in the kodesh kodoshim. answers that the sprinkling was done while the kohen R’ Elazar’s qualification is unsuccessfully challenged. -

Fine Judaica: Printed Books, Manuscripts, Holy Land Maps & Ceremonial Objects, to Be Held June 23Rd, 2016

F i n e J u d a i C a . printed booKs, manusCripts, holy land maps & Ceremonial obJeCts K e s t e n b au m & C om pa n y thursday, Ju ne 23r d, 2016 K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 147 Catalogue of F i n e J u d a i C a . PRINTED BOOK S, MANUSCRIPTS, HOLY LAND MAPS & CEREMONIAL OBJECTS INCLUDING: Important Manuscripts by The Sinzheim-Auerbach Rabbinic Dynasty Deaccessions from the Rare Book Room of The Hebrew Theological College, Skokie, Ill. Historic Chabad-related Documents Formerly the Property of the late Sam Kramer, Esq. Autograph Letters from the Collection of the late Stuart S. Elenko Holy Land Maps & Travel Books Twentieth-Century Ceremonial Objects The Collection of the late Stanley S. Batkin, Scarsdale, NY ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Thursday, 23rd June, 2016 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand: Sunday, 19th June - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Monday, 20th June - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Tuesday, 21st June - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Wednesday, 22nd June - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm No Viewing on the Day of Sale This Sale may be referred to as: “Consistoire” Sale Number Sixty Nine Illustrated Catalogues: $38 (US) * $45 (Overseas) KESTENBAUM & COMPANY Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 242 West 30th Street, 12th Floor, New York, NY 10001 • Tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 E-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web Site: www.Kestenbaum.net K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . -

The Picture Can't Be Displayed

The picture can't be displayed. Table of Contents Preface ............................................................................................................................... 1 Balancing Hishtadlut and Bitachon in the Workplace (Ike Sultan) ..................................................... 1 Earliest Time to Daven (Judah Kerbel) ....................................................................................... 4 Entering a Non-Kosher Restaurant (Ariel Schreier) ........................................................................ 5 Paying Workers on Time (Judah Kerbel) ...................................................................................... 6 Shmitat Kesafim and Pruzbul (Dani Yaros) ................................................................................. 7 Ribbis for Corporations (Ike Sultan) ........................................................................................... 9 Hasagat Gevul and Unfair Competition (Dubbin Hanon) .............................................................. 11 Onaa (Dubbin Hanon) .......................................................................................................... 13 Tearing Keriya for a Patient (Natie Elkaim) ............................................................................... 16 Negiah and Yichud Issues (Alex Mermelstein) ............................................................................. 17 Taking Money for Learning and Teaching Torah (Robbie Schrier) ..................................................... 18 -

The Ohr Somayach Torah Magazine on the Internet • O H R N E T Shabbat Parshat Lech Lecha • 13 Cheshvan 5767 • Nov

THE OHR SOMAYACH TORAH MAGAZINE ON THE INTERNET • WWW.OHR.EDU O H R N E T SHABBAT PARSHAT LECH LECHA • 13 CHESHVAN 5767 • NOV. 4, 2006 • VOL. 14 NO. 3 PARSHA INSIGHTS You are not in control. It’s wonderfully relaxing. THE HITCHHIKER’S GUIDE TO ETERNITY No one in his right mind hitchhikes to an important business meeting or to catch an airplane. The very act of “Go for yourself…” hitchhiking says, “I’m prepared to be where I am. I don’t any years ago in a more naive and somewhat need to be anywhere else.” A hitchhiker feels the presence of hashgacha (Divine safer world, I once hitchhiked from Amsterdam supervision). My life is not in my control. All I have is the Mto Pisa in Italy. present. And therefore I must live in this moment and be Only the young and the reckless (and I was both) here now. would climb aboard the rear seat of a BMW 900 motor- That’s why hitchhiking is a great calmer. (No, I don’t cycle on a night of driving rain with a 50 pound pack mean karma.) strapped to one’s back (This placed my center of gravity A Jew’s job is to live in the present, but not for the somewhere past the outer extremity of the rear wheel.) present. Much of our lives are spent thinking about what Every time the rider accelerated, the backpack dragged might happen, or what might not happen, or where I me backwards off the bike. The autobahn was a sea of could be/should be now, or what went wrong or what rain. -

The Magic of the Mezuzah in Rabbinic Literature

THE MAGIC OF THE MEZUZAH IN RABBINIC LITERATURE Eva-Maria Jansson Lund The notion that the mezuzah — the capsule containing a parchment strip on which is written Deut. 6:4-9 and 11:13-21 and which is attached to the doorposts of a Jewish home — is protective has been explained in different ways. Two different developments have been suggested: either the mezuzah was originally an amulet, which the Rabbis sought to theologize, or it was a religious object which fell victim to popular superstitious notions'. In this paper, where the study is delimited to the Talmudic and some Geonic material, I intend to propose another explanation to the origin and development of the idea of its protectiveness. The origin of the mezuzah as an object is obscure. The oldest references we have to it, e.g. in the Mishnah and the Tosefta, presuppose that it is an object on par with other religious objects, and that the affixing of the mezuzah is a mitsvah. To conclude that traditions found in later texts, regarding it as an amulet, are pre-Rabbinic and preserved unaffected by the Rabbinic mediation, is problematic. Discerning a popular influence, that is, a popular strata in the Talmudim, the She'iltot, Sefer Halakhot Gedolot and the Hekhalot literature, opposed to the views of the Rabbinic elite, is also difficult'. The statements in the Talmudim relating to the mezuzah can roughly be divided in two groups. The first one contains the statements concerning the physical execution of the mitsvah, what one might call the »technicalities«: what kind of leather to use, what ink to use, the layout of the text on the parchment, how to roll this etc. -

Torah for the Times of the Redemption Dedicated in Memory of Cantor Jerome L

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • YU Center for the Jewish Future THE BENJAMIN AND ROSE BERGER TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman z"l and Ann Arbesfeld APRIL 2020 • YOM HAATZMAUT 5780 Torah For The Times Of The Redemption Dedicated in memory of Cantor Jerome L. Simons We thank the following synagogues which have pledged to be Pillars of the Torah To-Go® project Beth David Synagogue Cong. Ohr HaTorah Young Israel of West Hartford, CT Atlanta, GA Lawrence-Cedarhurst Cedarhurst, NY Beth Jacob Congregation Cong. Shaarei Tefillah Beverly Hills, CA Newton Centre, MA Young Israel of New Hyde Park Beth Jacob Congregation Green Road Synagogue New Hyde Park, NY Oakland, CA Beachwood, OH Young Israel of Bnai Israel – Ohev Zedek The Jewish Center Philadelphia, PA New York, NY New Rochelle New Rochelle, NY Boca Raton Synagogue Jewish Center of Young Israel of Boca Raton, FL Brighton Beach Brooklyn, NY Scarsdale Cong. Ahavas Achim Scarsdale, NY Highland Park, NJ Koenig Family Young Israel of Foundation Cong. Ahavath Torah Brooklyn, NY West Hartford Englewood, NJ West Hartford, CT Yeshivat Reishit Cong. Beth Sholom Beit Shemesh/Jerusalem Young Israel of Lawrence, NY Israel West Hempstead Cong. Beth Sholom West Hempstead, NY Young Israel of Providence, RI Century City Young Israel of Cong. Bnai Yeshurun Los Angeles, CA Woodmere Teaneck, NJ Woodmere, NY Young Israel of Cong. Ohab Zedek Hollywood Ft Lauderdale New York, NY Hollywood, FL Rabbi Dr. Ari Berman, President, Yeshiva University Rabbi Yaakov Glasser, David Mitzner Dean, Center for the Jewish Future Rabbi Menachem Penner, Max and Marion Grill Dean, Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary Rabbi Robert Shur, Series Editor Rabbi Joshua Flug, General Editor Rabbi Michael Dubitsky, Content Editor Andrea Kahn, Copy Editor Copyright © 2020 All rights reserved by Yeshiva University Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future 500 West 185th Street, Suite 419, New York, NY 10033 • [email protected] • 212.960.0074 This publication contains words of Torah.