Pin-Up Art, Interpreting the Dynamics of Style

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

®L)T Finjtn Lejus-®Lisenitr O the LINDEN NEWS, Eetablished 1927

< t 0 ®l)t finJtn lejus-®lisenitr O The LINDEN NEWS, eetablished 1927. combined with The LINDEN OBSERVER, established 1920. Entered second class ma.. nui’er PRICE: 5 Cents Vol. II, No. 45 8 PAGES LINDEN, N. J, THURSDAY, MAY 2, 1957 fie I '■ *1' L ‘‘ d e'i. N J * LINDEN Linden Library Director ^ I.iiideii Dancer ^Know Yourf Fealiircal in Oh io SCENE To Assume State Chair | Viola Maihl, director o f : Policeman Robert F. Lohr of 1309 Thel ti.e Linden Public Library, who by PETE BARTUS ma terrace, a senior at the New ha.< been .serving a.s chairman of Brunswick evening division of the library development commit Rutgers University, has been tee of the New Jersey Library A.s- Patrolman George Modrak lives 1 elected to the Hutger.s Honor .sociation, will become pre.sident- a. 319 CurtLs Street and was bom i Society ,the top honor group of elect of the state organization at in Ne-«' York City on September j the four evening branches of the annual .spring conference, to 12, 1928. He attended Public j University College, it ha.s been be held at the Hotel Berkeley- School No. l , j announced by the University. Carteret, Asbury Park, on May 2, Linden Jr. High Initiation of the twenty-six men S, and 4. School, and -v.-a.s | selected wil Ibe made on Satur Mi.s.s Harriet Proudfoot will be graduated from j day, April 27, at 7;00P.M. at come president of the Children’s Linden H ig h ; Zig’s Restaurant. -

Music & Entertainment Auction

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Plant (Director) Shuttleworth (Director) (Director) Music & Entertainment Auction 20th February 2018 at 10.00 For enquiries relating to the sale, Viewing: 19th February 2018 10:00 - 16:00 Please contact: Otherwise by Appointment Saleroom One, 81 Greenham Business Park, NEWBURY RG19 6HW Telephone: 01635 580595 Christopher David Martin David Howe Fax: 0871 714 6905 Proudfoot Music & Music & Email: [email protected] Mechanical Entertainment Entertainment www.specialauctionservices.com Music As per our Terms and Conditions and with particular reference to autograph material or works, it is imperative that potential buyers or their agents have inspected pieces that interest them to ensure satisfaction with the lot prior to the auction; the purchase will be made at their own risk. Special Auction Services will give indica- tions of provenance where stated by vendors. Subject to our normal Terms and Conditions, we cannot accept returns. Buyers Premium: 17.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 21% of the Hammer Price Internet Buyers Premium: 20.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24.6% of the Hammer Price Historic Vocal & other Records 9. Music Hall records, fifty-two, by 16. Thirty-nine vocal records, 12- Askey (3), Wilkie Bard, Fred Barnes, Billy inch, by de Tura, Devries (3), Doloukhanova, 1. English Vocal records, sixty-three, Bennett (5), Byng (3), Harry Champion (4), Domingo, Dragoni (5), Dufranne, Eames (16 12-inch, by Buckman, Butt (11 - several Casey Kids (2), GH Chirgwin, (2), Clapham and inc IRCC20, IRCC24, AGSB60), Easton, Edvina, operatic), T Davies(6), Dawson (19), Deller, Dwyer, de Casalis, GH Elliot (3), Florrie Ford (6), Elmo, Endreze (6) (39, in T1) £40-60 Dearth (4), Dodds, Ellis, N Evans, Falkner, Fear, Harry Fay, Frankau, Will Fyfe (3), Alf Gordon, Ferrier, Florence, Furmidge, Fuller, Foster (63, Tommy Handley (5), Charles Hawtrey, Harry 17. -

World War I Poster and Ephemera Collection: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c86h4kqh Online items available World War I Poster and Ephemera Collection: Finding Aid Finding aid prepared by Diann Benti. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Prints and Ephemera The Huntington Library 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 2014 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. World War I Poster and Ephemera priWWI 1 Collection: Finding Aid Overview of the Collection Title: World War I Poster and Ephemera Collection Dates (inclusive): approximately 1914-1919 Collection Number: priWWI Extent: approximately 700 items Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Prints and Ephemera 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection contains approximately 700 World War I propaganda posters and related ephemera dating from approximately 1914 to 1919. The posters were created primarily for government and military agencies, as well as private charities such as the American Committee for Relief in the Near East. While the majority of the collection is American, it also includes British and French posters, and a few Austro-Hungarian/German, Canadian, Belgian, Dutch, Italian, Polish, and Russian items. Language: English. Note: Finding aid last updated on July 24, 2020. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. -

Rolf Armstrong Biography

ARTIST BROCHURE Decorate Your Life™ ArtRev.com Rolf Armstrong Rolf Armstrong is best known for the calendar girl illustrations he produced for Brown and Bigelow's Dream Girl in 1919. Sometimes labeled the father of the American pin-up, his pastel illustrations set the glamour-art standard for feminine beauty that would dominate the genre for the next four decades. He was also noted for his portraits of silent film and motion picture stars as well as for his pin-ups and magazine covers. Armstrong was born in 1889 in Bay City, Michigan and settled in Bayside, New York on the shore of Little Neck Bay, while keeping his studio in Manhattan. His interest in art developed shortly after his family moved to Detroit in 1899. His earlier works are primarily 'macho' type sketches of boxers, sailors, and cowboys. Armstrong had previously been a professional boxer and accomplished seaman, and the ruggedly handsome artist was seldom seen without his yachting cap. He continued to sail his entire life and could be found sailing with movie stars such as James Cagney when the Armstrongs were in California. In fact, he was a winner of the Mab Trophy with his sailing canoe "Mannikin" and competed in other events at the Canoe championship of America held in the 1000 Islands in New York. Armstrong left Detroit for Chicago to attend the Art Institute of Chicago. While he was there he taught baseball, boxing, and art. New York became Armstrong's next home and magazine covers became his primary focus. His first was in 1912 for Judge magazine. -

VINTAGE POSTERS FEBRUARY 25 Our Annual Winter Auction of Vintage Posters Features an Exceptional Selection of Rare and Important Art Nouveau Posters

SCALING NEW HEIGHTS There is much to report from the Swann offices these days as new benchmarks are set and we continue to pioneer new markets. Our fall 2013 season saw some remarkable sales results, including our top-grossing Autographs auction to date—led by a handwritten Mozart score and a collection of Einstein letters discussing his general theory of relativity, which brought $161,000 each. Check page 7 for more post-sale highlights from the past season. On page 7 you’ll also find a brief tribute to our beloved Maps specialist Gary Garland, who is retiring after nearly 30 years with Swann, and the scoop on his replacement, Alex Clausen. Several special events are in the works for our winter and spring sales, including a talk on the roots of African-American Fine Art that coincides with our February auction, a partnership with the Library Company of Philadelphia and a discussion of the growing collecting field of vernacular photography. Make sure we have your e-mail address so you’ll receive our invites. THE TRUMPET • WINTER / SPRING 2014 • VOLUME 28, NUMBER 2 20TH CENTURY ILLUSTRATION JANUARY 23 Following the success of Swann’s first dedicated sale in this category, our 2014 auction features more excellent examples by famous names. There are magazine and newspaper covers and cartoons by R.O. Blechman, Jules Feiffer, David Levine, Ronald Searle, Edward Sorel, Richard Taylor and James Thurber, as well as works by turn-of-the-20th-century magazine and book illustrators such as Howard Chandler Christy and E.W. Kemble. Beloved children’s book artists include Ludwig Bemelmans, W.W. -

David Bowie's Urban Landscapes and Nightscapes

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 17 | 2018 Paysages et héritages de David Bowie David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text Jean Du Verger Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/13401 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.13401 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Jean Du Verger, “David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text”, Miranda [Online], 17 | 2018, Online since 20 September 2018, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/13401 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.13401 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text 1 David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text Jean Du Verger “The Word is devided into units which be all in one piece and should be so taken, but the pieces can be had in any order being tied up back and forth, in and out fore and aft like an innaresting sex arrangement. This book spill off the page in all directions, kaleidoscope of vistas, medley of tunes and street noises […]” William Burroughs, The Naked Lunch, 1959. Introduction 1 The urban landscape occupies a specific position in Bowie’s works. His lyrics are fraught with references to “city landscape[s]”5 and urban nightscapes. The metropolis provides not only the object of a diegetic and spectatorial gaze but it also enables the author to further a discourse on his own inner fragmented self as the nexus, lyrics— music—city, offers an extremely rich avenue for investigating and addressing key issues such as alienation, loneliness, nostalgia and death in a postmodern cultural context. -

Papers/Records /Collection

A Guide to the Papers/Records /Collection Collection Summary Collection Title: World War I Poster and Graphic Collection Call Number: HW 81-20 Creator: Cuyler Reynolds (1866-1934) Inclusive Dates: 1914-1918 Bulk Dates: Abstract: Quantity: 774 Administrative Information Custodial History: Preferred Citation: Gift of Cuyler Reynolds, Albany Institute of History & Art, HW 81-20. Acquisition Information: Accession #: Accession Date: Processing Information: Processed by Vicary Thomas and Linda Simkin, January 2016 Restrictions Restrictions on Access: 1 Restrictions on Use: Permission to publish material must be obtained in writing prior to publication from the Chief Librarian & Archivist, Albany Institute of History & Art, 125 Washington Avenue, Albany, NY 12210. Index Term Artists and illustrators Anderson, Karl Forkum, R.L. & E. D. Anderson, Victor C. Funk, Wilhelm Armstrong, Rolf Gaul, Gilbert Aylward, W. J. Giles, Howard Baldridge, C. LeRoy Gotsdanker, Cozzy Baldridge, C. LeRoy Grant, Gordon Baldwin, Pvt. E.E. Greenleaf, Ray Beckman, Rienecke Gribble, Bernard Benda, W.T. Halsted, Frances Adams Beneker, Gerritt A. Harris, Laurence Blushfield, E.H. Harrison, Lloyd Bracker, M. Leone Hazleton, I.B. Brett, Harold Hedrick, L.H. Brown, Clinton Henry, E.L. Brunner, F.S. Herter, Albert Buck, G.V. Hoskin, Gayle Porter Bull, Charles Livingston Hukari, Pvt. George Buyck, Ed Hull, Arthur Cady, Harrison Irving, Rea Chapin, Hubert Jack. Richard Chapman, Charles Jaynes, W. Christy, Howard Chandler Keller, Arthur I. Coffin, Haskell Kidder Copplestone, Bennett King, W.B. Cushing, Capt. Otho Kline, Hibberd V.B Daughterty, James Leftwich-Dodge, William DeLand, Clyde O. Lewis, M. Dick, Albert Lipscombe, Guy Dickey, Robert L. Low, Will H. Dodoe, William de L. -

Women Pin-Up Artists of the First Half of the Twentieth Century While M

Running Head: ALL AMERICAN GIRLS 1 All American Girls: Women Pin-Up Artists of the First Half of the Twentieth Century While male illustrators including Alberto Vargas (1896–1982), George Petty (1894–1975), and Gil Elvgren (1914–80) are synonymous with the field of early-twentieth-century pin-up art, there were, in fact, several women who also succeeded in the genre. Pearl Frush (1907–86), Zoë Mozert (1907–93), and Joyce Ballantyne (1918–2006) are three such women; each of whom established herself as a successful pin-up artist during the early to mid-twentieth century. While the critical study of twentieth-century pin-art is still a burgeoning field, most of the work undertaken thus far has focused on the origin of the genre and the work of its predominant artists who have, inevitably, been men. Women pin-up artists have been largely overlooked, which is neither surprising nor necessarily intentional. While illustration had become an acceptable means of employment for women by the late-nineteenth century, the pin-up genre of illustration was male dominated. In a manifestly sexual genre, it is not surprising that women artists would be outnumbered by their male contemporaries, as powerful middle-class gender ideologies permeated American culture well into the mid-twentieth century. These ideologies prescribed notions of how to live and present oneself—defining what it meant to be, or not be, respectable.1 One of the most powerful systems of thought was the domestic ideology, which held that a woman’s moral and spiritual presence was key to not only a successful home but also to the strength of a nation (Kessler-Harris 49). -

(045A222) PDF Pin up Calendar

PDF Pin Up Calendar - Adult Calendar - Bikini Calendar - Calendars 2020 - 2021 Wall Calendars - Retro Pin Ups 16 Month Wall Calendars By Avonside Megacalendars - download pdf Read Pin Up Calendar - Adult Calendar - Bikini Calendar - Calendars 2020 - 2021 Wall Calendars - Retro Pin ups 16 Month Wall Calendars by Avonside Ebook Download, Download Online Pin Up Calendar - Adult Calendar - Bikini Calendar - Calendars 2020 - 2021 Wall Calendars - Retro Pin ups 16 Month Wall Calendars by Avonside Book, Download Pin Up Calendar - Adult Calendar - Bikini Calendar - Calendars 2020 - 2021 Wall Calendars - Retro Pin ups 16 Month Wall Calendars by Avonside E-Books, Read Pin Up Calendar - Adult Calendar - Bikini Calendar - Calendars 2020 - 2021 Wall Calendars - Retro Pin ups 16 Month Wall Calendars by Avonside Online Free, Read Online Pin Up Calendar - Adult Calendar - Bikini Calendar - Calendars 2020 - 2021 Wall Calendars - Retro Pin ups 16 Month Wall Calendars by Avonside Ebook Popular, book pdf Pin Up Calendar - Adult Calendar - Bikini Calendar - Calendars 2020 - 2021 Wall Calendars - Retro Pin ups 16 Month Wall Calendars by Avonside, book pdf Pin Up Calendar - Adult Calendar - Bikini Calendar - Calendars 2020 - 2021 Wall Calendars - Retro Pin ups 16 Month Wall Calendars by Avonside, Download Online Pin Up Calendar - Adult Calendar - Bikini Calendar - Calendars 2020 - 2021 Wall Calendars - Retro Pin ups 16 Month Wall Calendars by Avonside Book, Download pdf Pin Up Calendar - Adult Calendar - Bikini Calendar - Calendars 2020 - 2021 Wall Calendars -

This Is the Preprint Version of the Article the Rise and Fall of Ziggy

This is the preprint version of the article Robbie Skyes and Kieran Tranter ‘The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and Natural Law’ (2018) International Journal for the Semiotics of Law. DOI 10.1007/s11196-018-9542-4 It can be downloaded at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11196-018-9542-4 The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and Natural Law Abstract In Natural Law and Natural Rights, John Finnis delves into the past, attempting to revitalise the Thomist natural law tradition cut short by opposing philosophers such as David Hume. In this article, Finnis’s efforts at revival are assessed by way of comparison with – and, indeed, contrast to – the life and art of musician David Bowie. In spite of their extravagant differences, there exist significant points of connection that allow Bowie to be used in interpreting Finnis’s natural law. Bowie’s work – for all its appeals to a Nietzschean ground zero for normative values – shares Finnis’s concern with ordering affairs in a way that will realise humanity’s great potential. In presenting enchanted worlds and evolved characters as an antidote to all that is drab and pointless, Bowie has something to tell his audience about how human beings can thrive. Likewise, natural law holds that a legal system should include certain content that guides people towards a life of ‘flourishing’. Bowie and Finnis look to the past, plundering it for inspiration and using it as fuel to boost humankind forward. The analogy of Natural Law and Natural Rights and Bowie’s magpie-like relationship to various popular music traditions ultimately reveals that natural law theory is not merely an objective and unchanging edict to be followed without question, but a legacy that is to be recreated by those who carry it into the future. -

A Cultural Trade? Canadian Magazine Illustrators at Home And

A Cultural Trade? Canadian Magazine Illustrators at Home and in the United States, 1880-1960 A Dissertation Presented by Shannon Jaleen Grove to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor oF Philosophy in Art History and Criticism Stony Brook University May 2014 Copyright by Shannon Jaleen Grove 2014 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Shannon Jaleen Grove We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Michele H. Bogart – Dissertation Advisor Professor, Department of Art Barbara E. Frank - Chairperson of Defense Associate Professor, Department of Art Raiford Guins - Reader Associate Professor, Department of Cultural Analysis and Theory Brian Rusted - Reader Associate Professor, Department of Art / Department of Communication and Culture University of Calgary This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School Charles Taber Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation A Cultural Trade? Canadian Magazine Illustrators at Home and in the United States, 1880-1960 by Shannon Jaleen Grove Doctor of Philosophy in Art History and Criticism Stony Brook University 2014 This dissertation analyzes nationalisms in the work of Canadian magazine illustrators in Toronto and New York, 1880 to 1960. Using a continentalist approach—rather than the nationalist lens often employed by historians of Canadian art—I show the existence of an integrated, joint North American visual culture. Drawing from primary sources and biography, I document the social, political, corporate, and communication networks that illustrators traded in. I focus on two common visual tropes of the day—that of the pretty girl and that of wilderness imagery. -

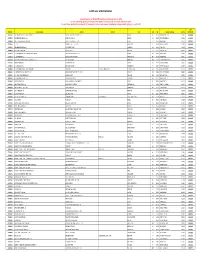

Certificates of Authorization

Certificates of Authorization Included below are all WV ACTIVE COAs licensed through June 30, 2015. As of the date of this posting, all Company COA updates received prior to February 11, 2015 are included. The next Roster posting will be in May 2015, immediately prior to renewal season, updating those in good standing through June 30, 2015. COA WV COA # Company Name Address 1 Address 2 City State Zip Engineer‐In‐Charge WV PE # EXPIRATION C04616‐00 2301 STUDIO, PLLC D.B.A. BLOC DESIGN, PLLC 1310 SOUTH TRYON STREET SUITE 111 CHARLOTTE NC 28203 WILLIAM LOCKHART 017282 6/30/2015 C04740‐00 3B CONSULTING SERVICES, LLC 140 HILLTOP AVENUE LEBANON VA 24266 PRESTON BREEDING 018263 6/30/2015 C04430‐00 3RD GENERATION ENGINEERING, INC. 7920 BELT LINE ROAD SUITE 591 DALLAS TX 75254 MARK FISHER 019434 6/30/2015 C02651‐00 4SE, INC. 7 RADCLIFFE STREET SUITE 301 CHARLESTON SC 29403 GEORGE BURBAGE 015290 6/30/2015 C04188‐00 4TH DIMENSION DESIGN, INC. 817 VENTURE COURT WAUKESHA WI 53189 JOHN GROH 019415 6/30/2015 C02308‐00 A & A CONSULTANTS, INC. 707 EAST STREET PITTSBURGH PA 15212 JACK ROSEMAN 007481 6/30/2015 C02125‐00 A & A ENGINEERING, CIVIL & STRUCTURAL ENGINEERS 5911 RENAISSANCE PLACE SUITE B TOLEDO OH 43623 OMAR YASEIN 013981 6/30/2015 C01299‐00 A 1 ENGINEERING, INC. 5314 OLD SAINT MARYS PIKE PARKERSBURG WV 26104 ROBERT REED 006810 6/30/2015 C03979‐00 A SQUARED PLUS ENGINEERING SUPPORT GROUP, LLC 3477 SHILOH ROAD HAMPSTEAD MD 21074 SHERRY ABBOTT‐ADKINS 018982 6/30/2015 C02552‐00 A&M ENGINEERING, LLC 3402 ASHWOOD LANE SACHSE TX 75048 AMMAR QASHSHU 016761 6/30/2015 C01701‐00 A.