Grimsby and Cleethorpes Place-Names By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trades. [Lincolnshire

740 DRA TRADES. [LINCOLNSHIRE. DRAPER8-{l()n tin ued. JILivingstone M. 22 North parade, Pimperton H . .A.Ingoldmells,Skegne8s Holland Frank, Coningsby, Lincoln Grantham Pinchbeck J.H. r63Hainton av.Grmsby Holland John, 193 & 195 Cleethorpe rd. tLocker William, 20 Market pLSleaford Plant Mrs. Lucy, Stickney, Boston Grimsby Loftus Mrs. L. 17 Sincil st. Lincoln Porter Mrs. Mary, Swinstead, Bourn Holland Wm. Hy. Swineshead, Boston Lord Frederick Fields, 125 to 1:35 Clee- tPorter W .High st.LongSutton, Wisb1:h Holmes Rubert, Tetney, Grimsby thorpe road, Grimsby Powley Mis-s Sarah Ann, 21 Rutland tHood Barnabas, High street, Alford Lunn Charles, New York, Lincoln street, Grimsby Horner John Henry, 3~ Upgate,Louth I!McFall Edward, Chauntry rd . .Alford Ramsden Thomas William, 55 Oxford Horsley J onn. So Church st.Gainsboro' I!Mclntosh D. ra, Chantry lane & 9 street, Grimsby & II7 Grimsby rdt. §Hotchen Mrs. Sarah Ann, 16 Dolphin Macaulay street, Grimsby & 26Market st.Cleethorpes,Grimsby lane, Boston Mackinder Maltby, South st . .Alford Banns Arthu.r Edward, 43 High st. tHoulton Chas. Rt. Glentham,Lincoln McLennan Mrs. K. rs Watergate, Cleethorpes, Grimsby §Howden Mrs. M. 42 High st. Boston Sleaford Rattenbury Jn. Wm.Skendleby, Splsby Howson W. S. Barnetby-le-·Wold, p!cLeod Angus, 9 Crescent, Spalding Redmore J. C. IS High st. Borncastlf~ Grimsby .Malkinson Herbt. 37 .Aswell st. Louth Renison Mrs. L. J. 124 .Albert street, tHudson Brothers, High street, Rusk Maltby James, 43 & SI· Humber st. Grimsby ington, Sleaford Cleethorpes, Grimsby , Reynolds A. J. The Terrace, Spilsby tHudson J. Castle Bytham, Grantham ~Maltby Richard,rB Market place,Lo•1th Richard son .Arth.2o W estgate, Sleafrd Humphrey Georg-e William, South Manchester & Bradford Warehouse Richardson Fredk. -

The Winter Camp of the Viking Great Army, Ad 872–3, Torksey, Lincolnshire

The Antiquaries Journal, 96, 2016, pp 23–67 © The Society of Antiquaries of London, 2016 doi:10.1017⁄s0003581516000718 THE WINTER CAMP OF THE VIKING GREAT ARMY, AD 872–3, TORKSEY, LINCOLNSHIRE Dawn M Hadley, FSA, and Julian D Richards, FSA, with contributions by Hannah Brown, Elizabeth Craig-Atkins, Diana Mahoney-Swales, Gareth Perry, Samantha Stein and Andrew Woods Dawn M Hadley, Department of Archaeology, University of Sheffield, Northgate House, West Street, Sheffield S14ET, UK. Email: d.m.hadley@sheffield.ac.uk Julian D Richards, Department of Archaeology, University of York, The King’s Manor, York YO17EP, UK. Email: [email protected] This paper presents the results of a multidisciplinary project that has revealed the location, extent and character of the winter camp of the Viking Great Army at Torksey, Lincolnshire, of AD 872–3. The camp lay within a naturally defended area of higher ground, partially surrounded by marshes and bordered by the River Trent on its western side. It is considerably larger than the Viking camp of 873–4 previously excavated at Repton, Derbyshire, and lacks the earthwork defences identified there. Several thousand individuals overwintered in the camp, including warriors, craftworkers and merchants. An exceptionally large and rich metalwork assemblage was deposited during the Great Army’s overwintering, and metal processing and trading was undertaken. There is no evidence for a pre-existing Anglo-Saxon trading site here; the site appears to have been chosen for its strategic location and its access to resources. In the wake of the overwintering, Torksey developed as an important Anglo-Saxon borough with a major wheel-thrown pottery industry and multiple churches and cemeteries. -

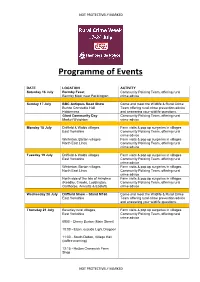

Programme of Events

NOT PROTECTIVELY MARKED Programme of Events DATE LOCATION ACTIVITY Saturday 16 July Barmby Feast Community Policing Team, offering rural Barmby Moor near Pocklington crime advice Sunday 17 July BBC Antiques Road Show Come and meet the Wildlife & Rural Crime Burton Constable Hall Team offering rural crime prevention advice Holderness and answering your wildlife questions. Giant Community Day Community Policing Team, offering rural Market Weighton crime advice Monday 18 July Driffield & Wolds villages Farm visits & pop up surgeries in villages East Yorkshire Community Policing Team, offering rural crime advice Winterton, Barton villages Farm visits & pop up surgeries in villages North East Lincs Community Policing Team, offering rural crime advice Tuesday 19 July Driffield & Wolds villages Farm visits & pop up surgeries in villages East Yorkshire Community Policing Team, offering rural crime advice Winterton, Barton villages Farm visits & pop up surgeries in villages North East Lincs Community Policing Team, offering rural crime advice North side of the Isle of Axholme Farm visits & pop up surgeries in villages (Keadby, Crowle, Luddington, Community Policing Team, offering rural Garthorpe, Amcotts & Eastoft) crime advice Wednesday 20 July Driffield Show – Stand M160 Come and meet the Wildlife & Rural Crime East Yorkshire Team offering rural crime prevention advice and answering your wildlife questions. Thursday 21 July Beverley rural villages, Farm visits & pop up surgeries in villages East Yorkshire Community Policing Team, offering rural -

LINCOLNSHIRE. [ Kl:'LLY's

- 780 FAR LINCOLNSHIRE. [ Kl:'LLY's F ARMER~-continued. Anderson Charles, Epworth, Doncaster Atldn Geo. Common, Crowland, Peterboro' Abraham Everatt, Barnetby-le-Wold R.S.O Anderson G. High st. Long Sutton, Wisbech Atltin Geo. Hy. West Pinchbeck, Spalding Abrabam Henry, Aunsby, Sleaford Anderson John, High st. Barton-on-Humber Atkin John, Mareham-le-Fen, Boston Abrnham Jn. Otby ho. Walesby,:Market Ra.sen Anderson John, Epworth, Doncaster Atkin John, Skidbrook, Great Grimsby Ahraham S. Toft ho. Wainfieet St.Mary R.S.O AndersonJn. j un. Chapel farm, Brtn. -on-Hm br A tkin J n. Wm. The Gipples, Syston, G rantham Abraha.m William, Croxby, Caistor AndersonR. Waddinghm.KirtonLindseyR.S.O Atkin Joseph, Bennington, Boston Abrahams Wm. Park, Westwood side,Bawtry Anderson Samuel, Anderby, Alford Atkin Richard, Withern, Alford Aby Edward, Thornton Curtis, Ulceby Andrew Charles, North Fen, Bourn Atkin Tom, Cowbit, Spalding Aby Mrs. Mary & Joseph, Cadney, Brigg Andrew Edwd. Grubb hi. Fiskerton, Lincoln Atkin Tom, Moulton, Spalding Achurch Hy.Engine bank, Moulton, Spalding Andrew James Cunnington, Fleet, Holbeach Atkin William, Fosdyke, Spalding Achurc;h J.DeepingSt.James,Market Deeping Andrew John, Deeping St. Nicholas, Pode AtkinWm.Glebe frrn. Waddington hth.Lincln Acrill William, Fillingham, Lincoln Hole, Spalding Atkin William, Swineshead, Spalding Adams Mrs. Ann, Craise Lound, Bawtry Andrew John, Gunby, Grantham Atkin William, Whaplode, Spalding Adarns George, Epworth, Doncaster Andrew John, 5 Henrietta. street, Spalding Atkins George, Mill lane, South Somercotes, Adarns Isaac Crowther, Stow park, Lincoln Andrew John, Hunberstone, Great Grimsby Great Grimsby Adams John, Collow grange, Wragby Andrew John, Somerby, Grantham Atkinson Jsph. & Jas. Pointon, Falkingham Adams Luther, Thorpe-le-Yale, Ludford, Andrew J oseph, Butterwick, Boston Atkinson Abraharn,Sea end,Moulton,Spaldng Market Rasen Andrew Willey,South Somercotes,Gt.Grmsby Atkinson Abraham, Skellingthorpe, Lincoln Adcock Charles, Corby, Grantham Andrcw Wm. -

The Full Job Description

GRIMSBY TOWN FOOTBALL CLUB JOB DESCRIPTION Job Title )DFLOLWLHV0DQDJHU (including6WDGLXP Matchday Safety Officer) Department Health & Safety Reports to Chief Executive Officer (CEO) Hours of work Due to the nature of the appointment, flexibility is required and hours will vary (including evenings, weekends and Bank Holidays) in accordance with the operational needs of the business. The role will require, at times the working week to be in excess of 40 hours, with lieu time offered to compensate. Purpose of the post (Day to Day) All aspects of Health & Safety, including compliance, inspections and testing at all venues either owned or leased by Grimsby Town Football Club including training where required. To deliver all aspects of safety, as defined in the Club’s Safety Certificate as prescribed by North East Lincolnshire Council, the Safety Advisory Group and the Sports Ground Safety Authority. Purpose of the post (Event Day) To ensure, as far as reasonably possible, the safety of everyone attending regulated Football or other events at the home of Grimsby Town Football Club, in accordance with the Club’s Safety Certificate’s Terms and Conditions and the Club’s Statement of Intent for Spectator Safety. This also applies to any other venue operating or leased for the purpose of spectator events on behalf of Grimsby Town Football Club including Academy activities. The post holder shall have no other duties on a match/event day, other than those involved in the execution of the role of Safety Officer. Duties and Responsibilities: • Carry -

Road Investment Strategy: Overview

Road Investment Strategy: Overview December 2014 Road Investment Strategy: Overview December 2014 The Department for Transport has actively considered the needs of blind and partially sighted people in accessing this document. The text will be made available in full on the Department’s website. The text may be freely downloaded and translated by individuals or organisations for conversion into other accessible formats. If you have other needs in this regard please contact the Department. Department for Transport Great Minster House 33 Horseferry Road London SW1P 4DR Telephone 0300 330 3000 Website www.gov.uk/dft General enquiries https://forms.dft.gov.uk ISBN: 978-1-84864-148-8 © Crown copyright 2014 Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with the Crown. You may re-use this information (not including logos or third-party material) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or e-mail: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third-party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum. Photographic acknowledgements Alamy: Cover Contents 3 Contents Foreword 5 The Strategic Road Network 8 The challenges 9 The vision 10 The Investment Plan 13 The Performance Specification 22 Transforming our roads 26 Appendices: regional profiles 27 The Road Investment Strategy suite of documents (Strategic Vision, Investment Plan, Performance Specification, and this Overview) are intended to fulfil the requirements of Clause 3 of the Infrastructure Bill 2015 for the 2015/16 – 2019/20 Road Period. -

Hornsea One and Two Offshore Wind Farms About Ørsted | the Area | Hornsea One | Hornsea Two | Community | Contact Us

March 2019 Community Newsletter Hornsea One and Two Offshore Wind Farms About Ørsted | The area | Hornsea One | Hornsea Two | Community | Contact us Welcome to the latest community newsletter for Hornsea One and Two Just over a year ago we began offshore construction on Hornsea One, and now, 120 km off the coast, the first of 174 turbines have been installed and are generating clean, renewable electricity. Following a series of local information events held along our onshore cable route, the onshore construction phase for Hornsea Two is now underway. We will continue to work to the highest standards already demonstrated by the teams involved, and together deliver the largest renewable energy projects in the UK. Kingston Upon Hull Duncan Clark Programme Director, Hornsea One and Two We are a renewable energy company with the vision to create a world About that runs entirely on green energy. Climate change is one of the biggest challenges for life on earth; we need to transform the way we power the Ørsted world. We have invested significantly in the UK, where we now develop, construct and operate offshore wind farms and innovative biotechnology which generates energy from household waste without incineration. Over the last decade, we have undergone a truly green transformation, halving our CO2 emissions and focusing our activities on renewable sources of energy. We want to revolutionise the way we provide power to people by developing market leading green energy solutions that benefit the planet and our customers alike. March 2019 | 2 About -

Tree Preservation Order Register (As of 13/03/2019)

North East Lincolnshire - Tree Preservation Order Register (as of 13/03/2019) TPO Ref Description TPO Status Served Confirmed Revoked NEL252 11 High Street Laceby Confirmed 19/12/2017 05/06/2018 NEL251 Land at 18, Humberston Avenue, Humberston Lapsed 06/10/2017 NEL245 Land at The Becklands, Waltham Road, Barnoldby Le Beck Served 08/03/2019 NEL244 104/106, Caistor Road, Laceby Confirmed 12/02/2018 06/08/2018 NEL243 Land at Street Record, Carnoustie, Waltham Confirmed 24/02/2016 27/05/2016 NEL242 Land at 20, Barnoldby Road, Waltham Confirmed 24/02/2016 27/05/2016 NEL241 Land at Peartree Farm, Barnoldby Road, Waltham Confirmed 24/02/2016 27/05/2016 NEL240 Land at 102, Laceby Road, Grimsby Confirmed 01/02/2016 27/05/2016 NEL239 Land at 20, Scartho Road, Grimsby Confirmed 06/11/2014 10/03/2015 NEL238 Land at The Cedars, Eastern Inway, Grimsby Confirmed 21/11/2014 10/03/2015 NEL237 Land at 79, Weelsby Road, Grimsby Revoked 23/07/2014 10/03/2015 NEL236 Land at 67, Welholme Avenue, Grimsby Confirmed 21/03/2014 21/08/2014 NEL235 Land at 29-31, Chantry Lane, Grimsby Confirmed 10/02/2014 21/08/2014 NEL234 Land at Street Record,Main Road, Aylesby Confirmed 21/06/2013 09/01/2014 NEL233 Land at 2,Southern Walk, Grimsby Confirmed 12/08/2013 09/01/2014 NEL232 34/36 Humberston Avenue Confirmed 11/06/2013 28/01/2014 NEL231 Land at Gedney Close, Grimsby Confirmed 06/03/2013 19/11/2013 NEL230 Land at Hunsley Crescent, Grimsby Confirmed 04/03/2013 19/11/2013 NEL229 Land at 75,Humberston Avenue, Humberston Confirmed 16/01/2013 12/02/2013 NEL228 Land at St. -

Excavations at Aylesby, South Humberside, 1994

EXCAVATIONS AT AYLESBY, SOUTH HUMBERSIDE, 1994 Ken Steedman and Martin Foreman Re-formatted 2014 by North East Lincolnshire Council Archaeological Services This digital report has been produced from a hard/printed copy of the journal Lincolnshire History and Archaeology (Volume 30) using text recognition software, and therefore may contain incorrect words or spelling errors not present in the original. The document remains copyright of the Society for Lincolnshire History and Archaeology and the Humberside Archaeology Unit and their successors. This digital version is also copyright of North East Lincolnshire Council and has been provided for private research and education use only and is not for reproduction, distribution or commercial use. Front Cover: Aylesby as it may have looked in the medieval period, reconstructed from aerial photographs and excavated evidence (watercolour by John Marshall). Image reproduced courtesy of the Society for Lincolnshire History & Archaeology © 1994 CONTENTS EXCAVATIONS AT AYLESBY, SOUTH HUMBERSIDE, 1994 ........................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 1 SELECT DOCUMENTARY EVIDENCE FOR THE PARISH OF AYLESBY ................................. 3 PREVIOUS ARCHAEOLOGICAL WORK ........................................................................................ 8 THE EXCAVATIONS ...................................................................................................................... -

7.6.5.07 Local Receptors for Landfall and Cable Route

Environmental Statement Volume 6 – Onshore Annex 6.5.7 Representative Visual Receptors for Landfall and Cable Route PINS Document Reference: 7.6.5.7 APFP Regulation 5(2)(a) January 2015 SMart Wind Limited Copyright © 2015 Hornsea Offshore Wind Farm Project Two –Environmental Statement All pre-existing rights reserved. Volume 6 – Onshore Annex 6.5.7 - Local Receptors for Landfall and Cable Route Liability This report has been prepared by RPS, with all reasonable skill, care and diligence within the terms of their contracts with SMart Wind Ltd or their subcontractor to RPS placed under RPS’ contract with SMart Wind Ltd as the case may be. Document release and authorisation record PINS document reference 7.6.5.7 Report Number UK06-050700-REP-0039 Date January 2015 Client Name SMart Wind Limited SMart Wind Limited 11th Floor 140 London Wall London EC2Y 5DN Tel 0207 7765500 Email [email protected] i Table of Contents 1 Public Rights of Way (as visual receptors) within 1 km of the cable route and landfall ........ 1 Table of Tables Table 1.1 Public Rights of Way (as visual receptors) within 1 km of the Landfall, Cable Route and Onshore HVDC Converter/HVAC Substation ..................................................... 1 Table of Figures Figure 6.5.7 Local Receptors ..................................................................................................... 6 ii 1 PUBLIC RIGHTS OF WAY (AS VISUAL RECEPTORS) WITHIN 1 KM OF THE CABLE ROUTE, LANDFALL AND ONSHORE HVDC CONVERTER/HVAC SUBSTATION Table 1.1 Public Rights of Way (as visual -

Station Travel Plan - Barnetby Introduction

Station Travel Plan - Barnetby Introduction What is a Station Travel Plan? The Department for Transport defines a Station Travel Plan as: “A strategy for managing the travel generated by your organisation, with the aim of reducing its environmental impact, typically involving support for walking, cycling, public transport and car sharing”. TransPennine Express maintains Station Travel Plans for all 19 stations where they are currently the Station Facility Owner (SFO). Why Develop a Station Travel Plan? Up until March 2020 demand for rail continued to grow, with more and more people choosing to travel by rail each year. It is predicted that, post the COVID-19 pandemic, within the next 30 years demand for rail will more than double. TransPennine Express is at the heart of this growth, with double digit percentage growth in passenger journeys year on year historically, with a doubling of customer numbers since the franchise was established in 2004. With growth of this magnitude, it is important that alongside investing in new trains, operating more services and enhancing the customer experience, we are considerate of how customers travel to and from the station to access the railway network. Against the landscape of a changing culture towards private transport, with many millennials choosing not to own a car, and instead adopt solutions such as Uber, dockless bike hire and car sharing schemes, a Station Travel Plan allows operators to identify the developments which are required to keep pace with society. It also allows us to identify key areas of change, with the evident shift from internal combustion to electric cars and hybrids, we are able to set out plans for providing the infrastructure to support this shift. -

Register of Landowner Deposits

Commons Act 2006 Deposit information Highways Act 1980, Section 31(6) Section 15A(1) Dates of deposit of Parish Ref. Title Date of initial deposit Expiry Date statement Ashby cum Fenby HA31(6) 1 Land at Grainsby Estate 27/02/2004 05/02/2014 Ashby cum Fenby HA31(6) 2 Woodland at Grainsby Estate 27/02/2004 05/02/2014 Ashby cum Fenby HA31(6) 3 Land at Grainsby Estate 06/02/2004 05/02/2014 Ashby cum Fenby HA31(6) 4 Land at Grainsby Estate 06/02/2004 05/02/2014 Ashby cum Fenby HA31(6) 5 Land forming part of Grainsby Estate 08/03/2004 05/02/2014 Ashby cum Fenby HA31(6) 6 Land forming part of Grainsby Estate 05/02/2004 05/02/2014 Ashby cum Fenby HA31(6) 8 Fenby Wood 05/02/2004 05/02/2014 Ashby cum Fenby HA31(6) 19 Fenby Wood 06/02/2004 06/02/2014 Ashby cum Fenby HA31(6) 10 South Farm, Thoroughfare Lane, Ashby 15/02/2008 15/02/2018 cum Fenby Ashby cum Fenby HA31(6) 11 Land being part of Grainsby Estate 21/02/2014 21/02/2034 21/02/2014 Ashby cum Fenby HA31(6) 12 Land being part of Grainsby Estate 21/02/2014 21/02/2034 21/02/2014 Ashby cum Fenby HA31(6) 13 Land at Hall Farm, Ashby cum Fenby 05/11/2018 06/11/2038 06/11/2018 Aylesby HA31(6) 14 Part of Home Farm, Aylesby 11/12/1996 11/12/2006 Aylesby HA31(6) 15 Part of Home Farm, Aylesby 11/12/1996 11/12/2006 Aylesby HA31(6) 16 Part of Home Farm, Aylesby 11/12/1996 11/12/2006 Aylesby HA31(6) 17 Part of Home Farm, Aylesby 11/12/1996 11/12/2006 Aylesby HA31(6) 18 Aylesby Manor, Grimsby 13/12/1996 13/12/2006 Aylesby HA31(6) 19 Part of Home Farm, Aylesby 18/02/1997 18/02/2006 Aylesby HA31(6) 20 Part of Home Farm, Aylesby 18/02/1997 18/02/2006 Aylesby HA31(6) 21 Part of Home Farm, Aylesby 18/02/1997 18/02/2006 Aylesby HA31(6) 22 Part of Home Farm, Aylesby 18/02/1997 18/02/2006 Aylesby HA31(6) 23 Part of Home Farm, Aylesby 18/02/1997 25/02/2007 Aylesby HA31(6) 24 Part of Home Farm, Aylesby 25/02/1997 27/02/2007 Commons Act 2006 Deposit information Highways Act 1980, Section 31(6) Section 15A(1) Dates of deposit of Parish Ref.