Responses to Critics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The RAVE Vertex Reconstruction Toolkit: Status and New Applications

The RAVE Vertex Reconstruction Toolkit: status and new applications Wolfgang Waltenberger, Fabian Moser and Winfried Mitaroff with contributions by Bernhard Pflugfelder and Herbert V. Riedel Austrian Academy of Sciences, Institute of High Energy Physics Nikolsdorfer Gasse 18, A-1050 Vienna, Austria, Europe Outline: • The RAVE toolkit and VERTIGO framework in short; • Improved track reconstruction by RAVE’s smoother; • Progress on the implementation of kinematics fitting; • Summary: present status and outlook to the future. W. Waltenberger, F.Moser, W. Mitaroff ALCPG ’07, Fermilab: 22–26 Oct. 2007 Reminder of the main goals 1. Creation of an extensible, detector-independent toolkit (RAVE) for vertex reconstruction, to be embedded into various environments: • RAVE = “Reconstruction (of vertices) in abstract versatile environments”; • The toolkit includes both vertex finding (a pattern recognition task a.k.a. track bundling) and vertex fitting (estimation of the vertex parameters and errors); • Synergy used: starting point was the old CMS software (ORCA) which has recently been refactored and ported to the new CMS framework (CMSSW); • Principal algorithmic assets are robustified reconstruction methods with estimators based on adaptive filters, thus downweighting the influence of outlier tracks; • RAVE is foreseen to stay source-code compatible with CMSSW, but thanks to its generic API may easily be embedded into other software environments. 2. Creation of a simple stand-alone framework (VERTIGO) for fast implemen- tation, debugging and analyzing of the core algorithms: • VERTIGO = “Vertex reconstruction tools and interfaces to generic objets”; • Framework tools available: Visialization, Histogramming, a Vertex Gun for generating artificial test events, an LCIO input event generator, and a Data Harvester & Seeder for flexible I/O. -

Female Desire in the UK Teen Drama Skins

Female desire in the UK teen drama Skins An analysis of the mise-en-scene in ‘Sketch’ Marthe Kruijt S4231007 Bachelor thesis Dr. T.J.V. Vermeulen J.A. Naeff, MA 15-08-16 1 Table of contents Introduction………………………………..………………………………………………………...…...……….3 Chapter 1: Private space..............................................…….………………………………....….......…....7 1.1 Contextualisation of 'Sketch'...........................................................................................7 1.2 Gendered space.....................................................................................................................8 1.3 Voyeurism...............................................................................................................................9 1.4 Properties.............................................................................................................................11 1.5 Conclusions..........................................................................................................................12 Chapter 2: Public space....................……….…………………...……….….……………...…...…....……13 2.1 Desire......................................................................................................................................13 2.2 Confrontation and humiliation.....................................................................................14 2.3 Conclusions...........................................................................................................................16 Chapter 3: The in-between -

Skins Uk Download Season 1 Episode 1: Frankie

skins uk download season 1 Episode 1: Frankie. Howard Jones - New Song Scene: Frankie in her room animating Strange Boys - You Can't Only Love When You Want Scene: Frankie turns up at college with a new look Aeroplane - We Cant Fly Scene: Frankie decides to go to the party anyway. Fergie - Glamorous Scene: Music playing from inside the club. Blondie - Heart of Glass Scene: Frankie tries to appeal to Grace and Liv but Mini chucks her out, then she gets kidnapped by Alo & Rich. British Sea Power - Waving Flags Scene: At the swimming pool. Skins Series 1 Complete Skins Series 2 Complete Skins Series 3 Complete Skins Series 4 Complete Skins Series 5 Complete Skins Series 6 Complete Skins - Effy's Favourite Moments Skins: The Novel. Watch Skins. Skins in an award-winning British teen drama that originally aired in January of 2007 and continues to run new seasons today. This show follows the lives of teenage friends that are living in Bristol, South West England. There are many controversial story lines that set this television show apart from others of it's kind. The cast is replaced every two seasons to bring viewers brand new story lines with entertaining and unique characters. The first generation of Skins follows teens Tony, Sid, Michelle, Chris, Cassie, Jal, Maxxie and Anwar. Tony is one of the most popular boys in sixth form and can be quite manipulative and sarcastic. Michelle is Tony's girlfriend, who works hard at her studies, is very mature, but always puts up with Tony's behavior. -

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media Collide n New York University Press • NewYork and London Skenovano pro studijni ucely NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS New York and London www.nyupress. org © 2006 by New York University All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jenkins, Henry, 1958- Convergence culture : where old and new media collide / Henry Jenkins, p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Mass media and culture—United States. 2. Popular culture—United States. I. Title. P94.65.U6J46 2006 302.230973—dc22 2006007358 New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. Manufactured in the United States of America c 15 14 13 12 11 p 10 987654321 Skenovano pro studijni ucely Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: "Worship at the Altar of Convergence": A New Paradigm for Understanding Media Change 1 1 Spoiling Survivor: The Anatomy of a Knowledge Community 25 2 Buying into American Idol: How We are Being Sold on Reality TV 59 3 Searching for the Origami Unicorn: The Matrix and Transmedia Storytelling 93 4 Quentin Tarantino's Star Wars? Grassroots Creativity Meets the Media Industry 131 5 Why Heather Can Write: Media Literacy and the Harry Potter Wars 169 6 Photoshop for Democracy: The New Relationship between Politics and Popular Culture 206 Conclusion: Democratizing Television? The Politics of Participation 240 Notes 261 Glossary 279 Index 295 About the Author 308 V Skenovano pro studijni ucely Acknowledgments Writing this book has been an epic journey, helped along by many hands. -

Whitewashing Or Amnesia: a Study of the Construction

WHITEWASHING OR AMNESIA: A STUDY OF THE CONSTRUCTION OF RACE IN TWO MIDWESTERN COUNTIES A DISSERTATION IN Sociology and History Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by DEBRA KAY TAYLOR M.A., University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2005 B.L.A., University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2000 Kansas City, Missouri 2019 © 2019 DEBRA KAY TAYLOR ALL RIGHTS RESERVE WHITEWASHING OR AMNESIA: A STUDY OF THE CONSTRUCTION OF RACE IN TWO MIDWESTERN COUNTIES Debra Kay Taylor, Candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2019 ABSTRACT This inter-disciplinary dissertation utilizes sociological and historical research methods for a critical comparative analysis of the material culture as reproduced through murals and monuments located in two counties in Missouri, Bates County and Cass County. Employing Critical Race Theory as the theoretical framework, each counties’ analysis results are examined. The concepts of race, systemic racism, White privilege and interest-convergence are used to assess both counties continuance of sustaining a racially imbalanced historical narrative. I posit that the construction of history of Bates County and Cass County continues to influence and reinforces systemic racism in the local narrative. Keywords: critical race theory, race, racism, social construction of reality, white privilege, normality, interest-convergence iii APPROVAL PAGE The faculty listed below, appointed by the Dean of the School of Graduate Studies, have examined a dissertation titled, “Whitewashing or Amnesia: A Study of the Construction of Race in Two Midwestern Counties,” presented by Debra Kay Taylor, candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, and certify that in their opinion it is worthy of acceptance. -

The Promiscuous Estrogen Receptor: Evolution of Physiological Estrogens and Response to Phytochemicals and Endocrine Disruptors

The promiscuous estrogen receptor: evolution of physiological estrogens and response to phytochemicals and endocrine disruptors Michael E. Bakera,*, Richard Latheb,* a Division of Nephrology-Hypertension, Department of Medicine, 0693, University of California, San Diego, 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, California 92093-0693 b Division of Infection and Pathway Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Little France, Edinburgh *Corresponding authors E-mail addresses: [email protected] (M. Baker), [email protected] (R. Lathe). ABSTRACT Many actions of estradiol (E2), the principal physiological estrogen in vertebrates, are mediated by estrogen receptor-α (ERα) and ERβ. An important physiological feature of vertebrate ERs is their promiscuous response to several physiological steroids, including estradiol (E2), Δ5-androstenediol, 5α-androstanediol, and 27-hydroxycholesterol. A novel structural characteristic of Δ5-androstenediol, 5α-androstanediol, and 27-hydroxycholesterol is the presence of a C19 methyl group, which precludes the presence of an aromatic A ring with a C3 phenolic group that is a defining property of E2. The structural diversity of these estrogens can explain the response of the ER to synthetic chemicals such as bisphenol A and DDT, which disrupt estrogen physiology in vertebrates, and the estrogenic activity of a variety of plant-derived chemicals such as genistein, coumestrol, and resveratrol. Diversity in the A ring of physiological estrogens also expands potential structures of industrial chemicals that can act as endocrine disruptors. Compared to E2, synthesis of 27-hydroxycholesterol and Δ5-androstenediol is simpler, leading us, based on parsimony, to propose that one or both of these steroids or a related metabolite was a physiological estrogen early in the evolution of the ER, with E2 assuming this role later as the canonical estrogen. -

New Research: at Least 4 Million Koala Skins Sent to London Early Last Cent

New research: at least 4 million Koala skins sent to London Australian early last century Koala 24th August 2015 Foundation Australian Koala Foundation (AKF) research has revealed at least 8 million A.C.N. 010 922 102 Koalas were killed for the fur trade, with their pelts shipped to London, United States and Canada between 1888 and 1927. The AKF’s research sourced its figures from historic auction house records, news archives and other published works, but is looking to citizens of the UK for more information. Chief Executive of the AKF, Deborah Tabart, said that Koala fur is waterproof, and was used to make hats and gloves and to line coats. “Imagine if there are still people who have information about this dreadful trade?” Ms Tabart said. “Maybe you have a piece of Koala fur or item of clothing from this time, it’s all part of the jigsaw puzzle.” Ms Tabart said Australia’s Koala fur trade completely decimated wild populations. The current population of approximately 87,000 wild Koalas in Australia represents only 1 per cent of those that were shot for the fur trade. The AKF said this new research will be vitally important when it comes to regenerating Koala populations around the country in the future. “Where did they thrive before European settlers came?” she said. “Between 1888 and July 1918 our records show that at least 4,098,276 Koala furs passed through London auction houses,” she said. “This figure doesn’t include records from 1911 to 1914. “London wasn’t the only market – records we’ve obtained indicate more than 400,000 pelts were shipped in 1901 alone from Adelaide to the USA. -

Black Skin, White Masks (Get Political)

Black Skin, White Masks Fanon 00 pre i 4/7/08 14:16:58 <:IEA>I>86A www.plutobooks.com Revolution, Black Skin, Democracy, White Masks Socialism Frantz Fanon Selected Writings Forewords by V.I. Lenin Homi K. Edited by Bhabha and Paul Le Blanc Ziauddin Sardar 9780745328485 9780745327600 Jewish History, The Jewish Religion Communist The Weight Manifesto of Three Karl Marx and Thousand Years Friedrich Engels Israel Shahak Introduction by Forewords by David Harvey Pappe / Mezvinsky/ 9780745328461 Said / Vidal 9780745328409 Theatre of Catching the Oppressed History on Augusto Boal the Wing 9780745328386 Race, Culture and Globalisation A. Sivanandan Foreword by Colin Prescod 9780745328348 Fanon 00 pre ii 4/7/08 14:16:59 black skin whiteit masks FRANTZ FANON Translated by Charles Lam Markmann Forewords by Ziauddin Sardar and Homi K. Bhabha PLUTO PRESS www.plutobooks.com Fanon 00 pre iii 4/7/08 14:17:00 Originally published by Editions de Seuil, France, 1952 as Peau Noire, Masques Blanc First published in the United Kingdom in 1986 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA This new edition published 2008 www.plutobooks.com Copyright © Editions de Seuil 1952 English translation copyright © Grove Press Inc 1967 The right of Homi K. Bhabha and Ziauddin Sardar to be identifi ed as the authors of the forewords to this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 2849 2 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 2848 5 Paperback This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. -

Skins and the Impossibility of Youth Television

Skins and the impossibility of youth television David Buckingham This essay is part of a larger project, Growing Up Modern: Childhood, Youth and Popular Culture Since 1945. More information about the project, and illustrated versions of all the essays, can be found at: https://davidbuckingham.net/growing-up-modern/. In 2007, the UK media regulator Ofcom published an extensive report entitled The Future of Children’s Television Programming. The report was partly a response to growing concerns about the threats to specialized children’s programming posed by the advent of a more commercialized and globalised media environment. However, it argued that the impact of these developments was crucially dependent upon the age group. Programming for pre-schoolers and younger children was found to be faring fairly well, although there were concerns about the range and diversity of programming, and the fate of UK domestic production in particular. Nevertheless, the impact was more significant for older children, and particularly for teenagers. The report was not optimistic about the future provision of specialist programming for these age groups, particularly in the case of factual programmes and UK- produced original drama. The problems here were partly a consequence of the changing economy of the television industry, and partly of the changing behaviour of young people themselves. As the report suggested, there has always been less specialized television provided for younger teenagers, who tend to watch what it called ‘aspirational’ programming aimed at adults. Particularly in a globalised media market, there may be little money to be made in targeting this age group specifically. -

Week 6 Scorecard

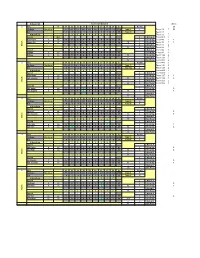

5/13/2021 Scorecard (Back 9) Skins 1 Hole In 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 In Points 13 Yardage Handicap 350 440 302 343 332 117 320 149 301 2654 Team #1 7 Team #1 7 33 Par 4 5 4 4 4 3 4 3 4 35 Team #7 Team #7 H Handicap 2 3 1 4 5 9 6 8 7 Team #2 7 Team #1 -17 Net 2 Match A Team #21 2 Nick Fischer 1 38 4 5 5 4 4 4 4 4 5 39 1 Show Up Team #3 2 1 h c Deacon Jim 2 37 4 5 4 5 4 4 4 4 5 39 78 1 Show Up Team #5 7 1 t a -1 3 2 Match B Team #6 2 M 2 3 1 4 5 9 6 8 7 75 1 Net Total Team #8 7 Team #7 -1 1 1 1 1 4 Match A Team #4 5 A-Player 5 35 5 6 4 4 5 3 4 4 5 40 Show Up Team #9 4 B-Player 6 35 5 5 5 4 5 3 5 4 4 41 81 Show Up Team #12 4 -1 1 1 1 1 4 11 Match B Team #20 5 78 Net Total Team #13 4 2 Hole 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 In Points Team #15 5 Yardage Handicap 350 440 302 343 332 117 320 149 301 2654 Team #2 7 Team #14 5 Par 4 5 4 4 4 3 4 3 4 35 Team #21 2 Team #19 4 H Handicap 2 3 1 4 5 9 6 8 7 Team #16 2 Team #2 -9 2 Match A Team #18 7 Kerry Brown 7 34 5 6 5 5 4 4 5 3 4 41 1 Show Up Team #17 6 1 h c Tom Jennings 8 34 4 5 5 4 5 3 7 3 6 42 83 1 Show Up Team #22 3 1 t a -9 1 1 15 2 Match B Team #23 2 M 2 3 1 4 5 9 6 8 7 68 1 Net Total Team #24 1 Team #21 -9 Match A Phil Hoefert 7 38 6 6 5 4 5 4 5 5 5 45 1 Show Up 1 Gary Osborne 7 34 5 7 5 3 5 4 4 4 4 41 86 1 Show Up 1 -11 14 Match B 72 Net Total 3 Hole 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 In Points Yardage Handicap 350 440 302 343 332 117 320 149 301 2654 Team #3 2 Par 4 5 4 4 4 3 4 3 4 35 Team #5 7 H Handicap 2 3 1 4 5 9 6 8 7 Team #3 -23 Match A Steve Hill 2 41 4 5 6 5 5 4 7 3 4 43 1 Show Up 1 h c Mike -

Investigating the Effects of Promiscuous Self-Presentation in Online Dating on Romantic

Investigating the effects of promiscuous self-presentation in online dating on romantic attraction and intention to date, and underlying perceptions of men and women Valerie den Ridder Snr 2018143 Master’s Thesis Communication and Information Sciences Specialization Business Communication & Digital Media School of Humanities and Digital Sciences Tilburg University, Tilburg Supervisor: Dr. Alexander Schouten Second reader: Tess van der Zanden July 2020 Table of contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................3 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................4 2. Literature review and hypotheses ....................................................................................6 2.1 Online dating ................................................................................................................6 2.2 Gender differences and attraction .................................................................................7 2.3 Promiscuous self-presentation and perception ............................................................ 12 3. Method ............................................................................................................................ 15 3.1 Participants ................................................................................................................ 15 3.2 Design ....................................................................................................................... -

Kaya Scodelario: from Teen Drama to Tinseltown

12 FEATURE artslondonnews.com Friday 00 November 2012 Kaya Scodelario: From teen drama to Tinseltown ‘’I went through a year of hating my- self at secondary school, I was bul- lied to the point of having to change schools because it got so bad’’ It seems the skins star, now age 23, al- most has bullies to thank for her rise to fame and her suc- sess. The English born beauty has now bro- ken America and is Kaya as Effy Stonem in Skins with co-starts Luke Pasqualino and Jack O’ Connell happily married. She charts much of her The Scorch Trials’ as 14 for a role in the her character being success down to a strong female lead gritty British teen dra- diagnosed with a Skins audition tak- ‘Teresa Agnes’. ma claiming that act- case of psychotic de- en on the off chance ing was the only thing pression (Series 4) after having to flee ‘’I could never see she had confidence Kaya commented schools due to cruel myself just playing in. saying she enjoyed bullies. Scodelar- the girlfriend or the depicting ‘the realistic io, born to a Brazil- love conquest, I Scodelario amassed trials and challenges’ ian mother, and an like meaty roles and success through her that Effy faced. English father, is intelligent roles for 4 years in Skins tak- best known for her women’’ ing on a whole range ‘I just want to keep breakthrough perfor- of challenging and working consist- mance as the elusive Despite having dys- thought provoking is- ently and do the job ‘Effy (Elizabeth) Sto- lexia and having ma- sues including trouble that I love, even if nem’ in Skins and jor