Confessions of Doping in Elite Sports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review of Criminalisation of Doping in Sport

Review of Criminalisation of Doping in Sport October 2017 Review of Criminalisation of Doping in Sport 1 of 37 Foreword The UK has always taken a strong stance against doping; taking whatever steps are necessary to ensure that the framework we have in place to protect the integrity of sport is fully robust and meets the highest recognised international standards. This has included becoming a signatory to UNESCO’s International Convention Against Doping in Sport; complying with the World Anti-Doping Code; and establishing UK Anti-Doping as our National Anti-Doping Organisation. However, given the fast-moving nature of this area, we can never be complacent in our approach. The developments we have seen unfold in recent times have been highly concerning, not least with independent investigations commissioned by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) revealing large scale state-sponsored doping in Russia. With this in mind, I tasked officials in my Department to undertake a Review to assess whether the existing UK framework remains sufficiently robust, or whether additional legislative measures are necessary to criminalise the act of doping in the UK. This Review was subsequently conducted in two stages: (i) a comprehensive assessment of the effectiveness of the UK’s existing anti-doping measures and compliance with WADA protocols, and (ii) targeted interviews with key expert stakeholders on the merits of strengthening UK anti-doping provisions, including the feasibility and practicalities of criminalising the act of doping. As detailed in this report, the Review finds that, at this current time, there is no compelling case to criminalise the act of doping in the UK. -

Armstrong.Pdf

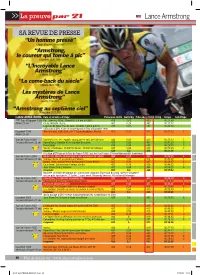

>> La preuve par 21 Lance Armstrong SA REVUE DE PRESSE “Un homme pressé” L’Equipe Magazine, 04.09.1993 “Armstrong, le coureur qui tombe à pic” L’Humanité, 05.07.1999 “L’Incroyable Lance Armstrong” L’Equipe, 12.07.1999 “Le come-back du siècle” L’Equipe, 26.07.1999 “Les mystères de Lance Armstrong” Le JDD, 27.06.2004 “Armstrong au septième ciel” Le Midi Libre, 25.07.2005 Lance ARMSTRONG Cols et victoires d’étape Puissance réelle watts/kg Puissance étalon 78 kg temps Cols Etape Tour Tour d’Espagne 1998 Pal. Jimenez 433w, 20min30s, 8,4 km à 6,49%, 418 5,65 400 00:21:49 4ème-27 ans Cerler. Montée courte. 462 6,24 442 00:11:33 Lagunas de Neila. Peu de vent, en forêt, 7 km à 8,57%, 415 5,61 397 00:22:18 Utilisation d’EPO et de cortisone durant le Tour d’Espagne 1998 Dauphiné 1999 Mont Ventoux CLM. ‘Battu de 1’1s par Vaughters. Record. 455 6,15 432 00:57:52 1 8ème-28 ans Tour de France 2004 La Mongie. 2ème derrière Basso 487 6,58 462 00:23:15 2 Tour de France 1999 Sestrières 1er. 1er «exploit» marquant en solo. Vent de face 448 6,05 420 00:27:13 5 1er puis déclassé-33 ans Beille 1er. En solitaire. 438 5,92 416 00:45:40 6 1er puis déclassé-28 ans Alpe d’Huez. Contrôle et se contente de suivre. 436 5,89 407 00:41:20 3 Chalimont 1er. Victoire à Villard de Lans 410 5,54 392 00:19:05 3 Piau Engaly 395 5,34 385 00:26:15 5 Alpe d’Huez CLM 1er. -

Peter Gammons: the Cleveland Indians, Best Run Team in Professional Sports March 5, 2018 by Peter Gammons 7 Comments PHOENIX—T

Peter Gammons: The Cleveland Indians, best run team in professional sports March 5, 2018 by Peter Gammons 7 Comments PHOENIX—The Cleveland Indians have won 454 games the last five years, 22 more than the runner-up Boston Red Sox. In those years, the Indians spent $414M less in payroll than Boston, which at the start speaks volumes about how well the Indians have been run. Two years ago, they got to the tenth inning of an incredible World Series game 7, in a rain delay. Last October they lost an agonizing 5th game of the ALDS to the Yankees, with Corey Kluber, the best pitcher in the American League hurt. They had a 22 game winning streak that ran until September 15, their +254 run differential was 56 runs better than the next best American League team (Houston), they won 102 games, they led the league in earned run average, their starters were 81-38 and they had four players hit between 29 and 38 homers, including 29 apiece from the left side of their infield, Francisco Lindor and Jose Ramirez. And they even drew 2.05M (22nd in MLB) to the ballpark formerly known as The Jake, the only time in this five year run they drew more than 1.6M or were higher than 28th in the majors. That is the reality they live with. One could argue that in terms of talent and human player development, the growth of young front office talent (6 current general managers and three club presidents), they are presently the best run organization in the sport, especially given their financial restraints. -

Social Psychology of Doping in Sport: a Mixed-Studies Narrative Synthesis

Social psychology of doping in sport: a mixed-studies narrative synthesis Prepared for the World Anti-Doping Agency By the Institute for Sport, Physical Activity and Leisure Review Team The review team comprised members of the Carnegie Research Institute at Leeds Beckett University, UK. Specifically the team included: Professor Susan Backhouse, Dr Lisa Whitaker, Dr Laurie Patterson, Dr Kelsey Erickson and Professor Jim McKenna. We would like to acknowledge and express our thanks to Dr Suzanne McGregor and Miss Alexandra Potts (both Leeds Beckett University) for their assistance with this review. Address for correspondence: Professor Susan Backhouse Institute for Sport, Physical Activity and Leisure Leeds Beckett University, Headingly Campus Leeds, LS6 3QS UK Email: [email protected] Web: www.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/ISPAL Disclaimer: The authors undertook a thorough search of the literature but it is possible that the review missed important empirical studies/theoretical frameworks that should be included. Also, judgement is inevitably involved in categorising papers into sample groups and there are different ways of representing the research landscape. We are not suggesting that the approach presented here is optimal, but we hope it allows the reader to appreciate the breadth and depth of research currently available on the social psychology of doping in sport. October 2015 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................. 6 Introduction -

Defense Witnesses Testify No Obstruction ; Marcuse Appears

Defense Witnesses Testify No Obstruction ; Marcuse Appears "Officials Never Declared Assembly Unlawful" by Mark Stadler said the link-ups did not stop contradicting earlier testimony News EdItor Saxon. Mahoney said the link-ups from Muir Dean Jim Beckley that Hearing officer Robert moved backwards, away from she had done so on two separate Lugannani heard Wednesday and Saxon. She said the individuals occasions. yesterday eight defense witnesses tried to maintain a steady distance All the witnesses except Mar testify 10 charged students did not from him at all times. cuse, who was present only at the violate University regulations at Quirk testified she never linked question and answer period, said the Nov. 25 demonstration over arms during the walk, directly Continued on Page 3 alleged UC ties with the CIA. The witnesses, who included San Diego Job Market: Be charged student Cookie Mahoney and Ruth Quirk and philosophy professor emeritus Herbert Marc use , testified in disciplinary Prepared to Start at Bottom hearings about the walk from the by Craig Jackson perience is imperative for many of gymnasium to Matthews campus Staff Writer these jobs because of the ex- taken by UC President Saxon If you are a June graduate with a treme specialization involved. following a question and answer BA in one of the social sciences, do She cited Texas as one region session with students at the gym not expect to find a good job in the where the rapid growth of industry steps. San Diego area. According to has made many more jobs The witnesses gave similar Noreen LYM, a labor market in- available. -

Gene… Sport Science 14 (2020) Suppl 1: 18-23

Mazzeo, F., et al.: New technology and no drugs in sport: gene… Sport Science 14 (2020) Suppl 1: 18-23 NEW TECHNOLOGY AND NO DRUGS IN SPORT: GENE DOPING REGULATION, EDUCATION AND RESEARCH Filomena Mazzeo1 and Antonio Ascione2 1Department of Sport Sciences and Wellness, Parthenope University, Naples, Italy 2University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, Italy Review paper Abstract This article examines the current state of genetic doping, the use of gene therapy in sports medicine, and the ethics of genetic improvement. The purpose of gene therapy is to use the foundations of genetic engineering for therapeutic use. Gene doping is a expansion of gene therapy. Innovative research in genetics and genomics will be used not only to diagnose and treat disease, but also to increase endurance and muscle mass. The first genetic therapy tests were conducted with proteins closely related to doping (e.g. erythropoietin and growth hormone). The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), an international organization created in 1999 to "promote, coordinate, and monitor the fight against doping in sport in all its forms," defines gene doping as the "nontherapeutic use of cells, genes, genetic elements, or modulation of gene expression, having the capacity to enhance performance" (World Anti-Doping Agency, 2008). This method represents a new Technology, but not devoid of adverse and fatal effects; gene doping could be dangerous for the athlete. The use of the athlete's biological-molecular passport represents a possible preventive and precautionary anti-doping strategy. The best way to prevent gene doping is a combination of regulation, education, research and the known of health risks. -

Fans Don't Boo Nobodies: Image Repair Strategies of High-Profile Baseball Players During the Steroid Era

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2011-09-23 Fans Don't Boo Nobodies: Image Repair Strategies of High-Profile Baseball Players During the Steroid Era Kevin R. Nielsen Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Communication Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Nielsen, Kevin R., "Fans Don't Boo Nobodies: Image Repair Strategies of High-Profile Baseball Players During the Steroid Era" (2011). Theses and Dissertations. 2876. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/2876 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Fans don't boo nobodies: Image repair strategies of high-profile baseball players during the Steroid Era Kevin Nielsen A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Steve Thomsen, Chair Kenneth Plowman Tom Robinson Department of Communications Brigham Young University December 2011 Copyright © 2011 Kevin Nielsen All Rights Reserved Fans don't boo nobodies: Image repair strategies of high-profile baseball players during the Steroid Era Kevin Nielsen Department of Communications, BYU Master of Arts Baseball's Steroid Era put many different high-profile athletes under pressure to explain steroid allegations that were made against them. This thesis used textual analysis of news reports and media portrayals of the athletes, along with analysis of their image repair strategies to combat those allegations, to determine how successful the athletes were in changing public opinion as evidenced through the media. -

Spitting in the Soup Mark Johnson

SPITTING IN THE SOUP INSIDE THE DIRTY GAME OF DOPING IN SPORTS MARK JOHNSON Copyright © 2016 by Mark Johnson All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic or photocopy or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher except in the case of brief quotations within critical articles and reviews. 3002 Sterling Circle, Suite 100 Boulder, Colorado 80301-2338 USA (303) 440-0601 · Fax (303) 444-6788 · E-mail [email protected] Distributed in the United States and Canada by Ingram Publisher Services A Cataloging-in-Publication record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. ISBN 978-1-937715-27-4 For information on purchasing VeloPress books, please call (800) 811-4210, ext. 2138, or visit www.velopress.com. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). Art direction by Vicki Hopewell Cover: design by Andy Omel; concept by Mike Reisel; illustration by Jean-Francois Podevin Text set in Gotham and Melior 16 17 18 / 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Introduction ...................................... 1 1 The Origins of Doping ............................ 7 2 Pierre de Coubertin and the Fair-Play Myth ...... 27 3 The Fall of Coubertin’s Ideal ..................... 41 4 The Hot Roman Day When Doping Became Bad ..................................... 55 5 Doping Becomes a Crime........................ 75 6 The Birth of the World Anti-Doping Agency ..... 85 7 Doping and the Cold War........................ 97 8 Anabolic Steroids: Sports as Sputnik .......... -

Jackie Robinson's 1946 Spring Training in Jim Crow Florida

The Unconquerable Doing the Impossible: Jackie Robinson's 1946 Spring Training in Jim Crow Florida To the student: As you read this accounting of Jackie Robinson's Jim Crow experience, ponder the following: • The role individuals played such as Rachel Robinson, Branch Rickey, Mary McLeod Bethune, Joe Davis and David Brock, Mayor William Perry, Clay Hopper, Johnny Wright, Wendell Smith, and Billy Rowe in shaping Robinson's response to the discrimination heaped upon him? • What factors, internal or external, enabled Jackie Robinson to succeed in his quest to cross baseball's color line? • The influence of ideas, human interests, such as the popularity of baseball and sport in American life, and the American consciousness • The impact of press coverage on human behavior and beliefs • The impact of World War II in reducing regionalism and replacing it with patriotic nationalism, civil rights organizations, enfranchisement and voting leverage, economic need and greed Los Angeles, February, 1946 On the late afternoon of February 28, 1946, Jack Roosevelt Robinson and his new bride, the former Rachel Isum, waited for their American Airlines flight from the Lockheed Terminal at the airport in Los Angeles, destined for Daytona Beach, Florida. Jack's attire was very proper, a gray business suit, while Rachel was splendidly outfitted in her new husband's wedding gifts, a three-quarter length ermine coat with matching hat and an alligator handbag. Although they had originally thought to travel by train, the Robinsons had decided to fly to New Orleans, then to Pensacola, and finally to Daytona Beach. There, Jack was to report by noon on March 1 to the training camp of the Montreal Royals, the top triple-A minor league farm team of the Brooklyn Dodgers baseball team. -

Coordinating Investigations and Sharing Anti-Doping Information and Evidence

Coordinating Investigations and Sharing Anti-Doping Information and Evidence May 2011 1. Introduction 1.1 Based on experience gained, evidence gathered, and lessons learned in the first ten years of its existence, it is WADA’s firm view that, to succeed in the fight against doping in sport, and so to protect the rights of clean athletes everywhere, Anti-Doping Organizations need to move beyond drug-testing alone to develop additional ways of gathering, sharing and exploiting information and evidence about the supply to and use of prohibited substances and methods by athletes under their jurisdiction. 1.2 While drug-testing will always remain an important part of the anti- doping effort, it is not capable on its own of uncovering and establishing most of the anti-doping rule violations in the World Anti- Doping Code that Anti-Doping Organizations must investigate and pursue. In particular, while the violations of presence and use of prohibited substances and methods can be uncovered by laboratory analysis of urine and blood samples collected from athletes, other anti- doping rule violations such as possession or administration of or trafficking in prohibited substances or methods can only be effectively identified and pursued through the collection of ‘non-analytical’ anti- doping information and evidence. 1.3 This means new investigative methods and techniques have to be deployed, and new partnerships have to be forged, particularly between the sports movement and public authorities engaged in the broader fight against doping in society. These new partnerships will allow Anti-Doping Organizations to take advantage of the investigative powers of those public authorities, including search and seizure, surveillance, and compulsion of witness testimony under penalties of perjury. -

Effects of Performance Enhancing Drugs on the Health of Athletes and Athletic Competition

S. HRG. 106–1074 EFFECTS OF PERFORMANCE ENHANCING DRUGS ON THE HEALTH OF ATHLETES AND ATHLETIC COMPETITION HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED SIXTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 20, 1999 Printed for the use of the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 75–594 PDF WASHINGTON : 2002 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 10:45 Jun 07, 2002 Jkt 075594 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 75594.TXT SCOM1 PsN: SCOM1 SENATE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION ONE HUNDRED SIXTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JOHN MCCAIN, Arizona, Chairman TED STEVENS, Alaska ERNEST F. HOLLINGS, South Carolina CONRAD BURNS, Montana DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii SLADE GORTON, Washington JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER IV, West Virginia TRENT LOTT, Mississippi JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas JOHN B. BREAUX, Louisiana OLYMPIA J. SNOWE, Maine RICHARD H. BRYAN, Nevada JOHN ASHCROFT, Missouri BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota BILL FRIST, Tennessee RON WYDEN, Oregon SPENCER ABRAHAM, Michigan MAX CLELAND, Georgia SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas MARK BUSE, Staff Director MARTHA P. ALLBRIGHT, General Counsel IVAN A. SCHLAGER, Democratic Chief Counsel and Staff Director KEVIN D. KAYES, Democratic General Counsel (II) VerDate 11-MAY-2000 10:45 Jun 07, 2002 Jkt 075594 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 75594.TXT SCOM1 PsN: SCOM1 C O N T E N T S Page Hearing held October 20, 1999 .............................................................................. -

(2018) Self- Censorship and the Pursuit of Truth in Sports Journalism – a Case Study of David Walsh

This is a peer-reviewed, post-print (final draft post-refereeing) version of the following published document and is licensed under All Rights Reserved license: Bradshaw, Tom ORCID: 0000-0003-0780-416X (2018) Self- censorship and the Pursuit of Truth in Sports Journalism – A Case Study of David Walsh. Ethical Space: The International Journal of Communication Ethics, 15 (1/2). Official URL: http://www.communicationethics.net/espace/ EPrint URI: http://eprints.glos.ac.uk/id/eprint/5636 Disclaimer The University of Gloucestershire has obtained warranties from all depositors as to their title in the material deposited and as to their right to deposit such material. The University of Gloucestershire makes no representation or warranties of commercial utility, title, or fitness for a particular purpose or any other warranty, express or implied in respect of any material deposited. The University of Gloucestershire makes no representation that the use of the materials will not infringe any patent, copyright, trademark or other property or proprietary rights. The University of Gloucestershire accepts no liability for any infringement of intellectual property rights in any material deposited but will remove such material from public view pending investigation in the event of an allegation of any such infringement. PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR TEXT. Self-censorship and the Pursuit of Truth in Sports Journalism – a case study of David Walsh Issues of self-censorship and potential barriers to truth-telling among sports journalists are explored through a case study of David Walsh, the award-winning Sunday Times chief sports writer, who is best known for his investigative work covering cycling.