Baseball Juiced Up: Should the Increased Risk Associated with the Use of Performance-Enhancing Substances Create Tort Liability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NCAA Division I Baseball Records

Division I Baseball Records Individual Records .................................................................. 2 Individual Leaders .................................................................. 4 Annual Individual Champions .......................................... 14 Team Records ........................................................................... 22 Team Leaders ............................................................................ 24 Annual Team Champions .................................................... 32 All-Time Winningest Teams ................................................ 38 Collegiate Baseball Division I Final Polls ....................... 42 Baseball America Division I Final Polls ........................... 45 USA Today Baseball Weekly/ESPN/ American Baseball Coaches Association Division I Final Polls ............................................................ 46 National Collegiate Baseball Writers Association Division I Final Polls ............................................................ 48 Statistical Trends ...................................................................... 49 No-Hitters and Perfect Games by Year .......................... 50 2 NCAA BASEBALL DIVISION I RECORDS THROUGH 2011 Official NCAA Division I baseball records began Season Career with the 1957 season and are based on informa- 39—Jason Krizan, Dallas Baptist, 2011 (62 games) 346—Jeff Ledbetter, Florida St., 1979-82 (262 games) tion submitted to the NCAA statistics service by Career RUNS BATTED IN PER GAME institutions -

Peter Gammons: the Cleveland Indians, Best Run Team in Professional Sports March 5, 2018 by Peter Gammons 7 Comments PHOENIX—T

Peter Gammons: The Cleveland Indians, best run team in professional sports March 5, 2018 by Peter Gammons 7 Comments PHOENIX—The Cleveland Indians have won 454 games the last five years, 22 more than the runner-up Boston Red Sox. In those years, the Indians spent $414M less in payroll than Boston, which at the start speaks volumes about how well the Indians have been run. Two years ago, they got to the tenth inning of an incredible World Series game 7, in a rain delay. Last October they lost an agonizing 5th game of the ALDS to the Yankees, with Corey Kluber, the best pitcher in the American League hurt. They had a 22 game winning streak that ran until September 15, their +254 run differential was 56 runs better than the next best American League team (Houston), they won 102 games, they led the league in earned run average, their starters were 81-38 and they had four players hit between 29 and 38 homers, including 29 apiece from the left side of their infield, Francisco Lindor and Jose Ramirez. And they even drew 2.05M (22nd in MLB) to the ballpark formerly known as The Jake, the only time in this five year run they drew more than 1.6M or were higher than 28th in the majors. That is the reality they live with. One could argue that in terms of talent and human player development, the growth of young front office talent (6 current general managers and three club presidents), they are presently the best run organization in the sport, especially given their financial restraints. -

Class 2 - the 2004 Red Sox - Agenda

The 2004 Red Sox Class 2 - The 2004 Red Sox - Agenda 1. The Red Sox 1902- 2000 2. The Fans, the Feud, the Curse 3. 2001 - The New Ownership 4. 2004 American League Championship Series (ALCS) 5. The 2004 World Series The Boston Red Sox Winning Percentage By Decade 1901-1910 11-20 21-30 31-40 41-50 .522 .572 .375 .483 .563 1951-1960 61-70 71-80 81-90 91-00 .510 .486 .528 .553 .521 2001-10 11-17 Total .594 .549 .521 Red Sox Title Flags by Decades 1901-1910 11-20 21-30 31-40 41-50 1 WS/2 Pnt 4 WS/4 Pnt 0 0 1 Pnt 1951-1960 61-70 71-80 81-90 91-00 0 1 Pnt 1 Pnt 1 Pnt/1 Div 1 Div 2001-10 11-17 Total 2 WS/2 Pnt 1 WS/1 Pnt/2 Div 8 WS/13 Pnt/4 Div The Most Successful Team in Baseball 1903-1919 • Five World Series Champions (1903/12/15/16/18) • One Pennant in 04 (but the NL refused to play Cy Young Joe Wood them in the WS) • Very good attendance Babe Ruth • A state of the art Tris stadium Speaker Harry Hooper Harry Frazee Red Sox Owner - Nov 1916 – July 1923 • Frazee was an ambitious Theater owner, Promoter, and Producer • Bought the Sox/Fenway for $1M in 1916 • The deal was not vetted with AL Commissioner Ban Johnson • Led to a split among AL Owners Fenway Park – 1912 – Inaugural Season Ban Johnson Charles Comiskey Jacob Ruppert Harry Frazee American Chicago NY Yankees Boston League White Sox Owner Red Sox Commissioner Owner Owner The Ruth Trade Sold to the Yankees Dec 1919 • Ruth no longer wanted to pitch • Was a problem player – drinking / leave the team • Ruth was holding out to double his salary • Frazee had a cash flow crunch between his businesses • He needed to pay the mortgage on Fenway Park • Frazee had two trade options: • White Sox – Joe Jackson and $60K • Yankees - $100K with a $300K second mortgage Frazee’s Fire Sale of the Red Sox 1919-1923 • Sells 8 players (all starters, and 3 HOF) to Yankees for over $450K • The Yankees created a dynasty from the trading relationship • Trades/sells his entire starting team within 3 years. -

Oakland Raiders 1

NNNorthN America’s Charity Fundraising “One Stop Shop” BW Unlimited is proud to provide this incredible list of hand signed Sports Memorabilia from around the U.S. All of these items come complete with a Certificate of Authenticity (COA) from a 3rd Party Authenticator. From Signed Full Size Helmets, Jersey’s, Balls and Photo’s …you can find everything you could possibly ever want. Please keep in mind that our vast inventory constantly changes and each item is subject to availability. When speaking to your Charity Fundraising Representative, let them know which items you would like in your next Charity Fundraising Event: Hand Signed Sports Memorabilia California Angels 1. Nolan Ryan Signed California Angels Jersey 7 No Hitters PSA/DNA (BWU001IS) $439 2. Nolan Ryan Signed California Angels 16x20 Photo SI & Ryan Holo (BWU001IS) $210 3. Nolan Ryan California Angels & Amos Otis Kansas City Royals Autographed 8x10 Photo -Pitching- (BWU001EPA) $172 4. Autographed Don Baylor Baseball Inscribed "MVP 1979" (BWU001EPA) $124 5. Rod Carew California Angels Autographed White Majestic Jersey (BWU001EPA) $304 6. Wally Joyner Autographed MLB Baseball (BWU001EPA) $148 7. Wally Joyner Autographed Big Stick Bat With His Name Printed On The Bat (BWU001EPA) $176 8. Wally Joyner California Angels Autographed Majestic Jersey (BWU001EPA) $280 9. Mike Witt Autographed MLB Baseball Inscribed "PG 9/30/84" (BWU001EPA) $148 L.A. Dodgers 1. Fernando Valenzuela Signed Dodgers Jersey (BWU001IS) $300 2. Autographed Fernando Valenzuela Baseball (BWU001EPA) $232 3. Autographed Fernando Valenzuela Los Angeles Dodgers White Majestic Jersey (BWU001EPA) $388 4. Duke Snider signed baseball (BWU001IS) $200 5. Tommy Lasorda signed jersey dodgers (BWU001IS) $325 6. -

Fans Don't Boo Nobodies: Image Repair Strategies of High-Profile Baseball Players During the Steroid Era

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2011-09-23 Fans Don't Boo Nobodies: Image Repair Strategies of High-Profile Baseball Players During the Steroid Era Kevin R. Nielsen Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Communication Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Nielsen, Kevin R., "Fans Don't Boo Nobodies: Image Repair Strategies of High-Profile Baseball Players During the Steroid Era" (2011). Theses and Dissertations. 2876. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/2876 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Fans don't boo nobodies: Image repair strategies of high-profile baseball players during the Steroid Era Kevin Nielsen A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Steve Thomsen, Chair Kenneth Plowman Tom Robinson Department of Communications Brigham Young University December 2011 Copyright © 2011 Kevin Nielsen All Rights Reserved Fans don't boo nobodies: Image repair strategies of high-profile baseball players during the Steroid Era Kevin Nielsen Department of Communications, BYU Master of Arts Baseball's Steroid Era put many different high-profile athletes under pressure to explain steroid allegations that were made against them. This thesis used textual analysis of news reports and media portrayals of the athletes, along with analysis of their image repair strategies to combat those allegations, to determine how successful the athletes were in changing public opinion as evidenced through the media. -

@Ongre ßß of Tlle Mnitù $¡Tutts MARK E

HENRY A WAXMAN. CALIFORNIA. TOM DAVIS, VIRGINIA, CHAIRMAN RANKING MINORTTY MEI\¡BER TOM LANTOS, CALIFORNIA ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS DAN BURTON, INDIANA EOOLPHUS TOWNS. NEW YORK CHFISTOPHER SHAYS, CONNECTICUI PAUL E. KANJORSKI, PENNSYLVANIA JOHN M. McHUGH, NEW YOBK CAFOLYN B. MALONEY, NEW YORK JOHN L. MICA, FLORIDA ELIJAH E. CUMMINGS, MARYLAND @ongre ßß of tlle Mnitù $¡tutts MARK E. SOUDEB, INDIANA DENNIS J. KUCINICH, OHIO TODD RUSSELL PLATTS, PENNSYLVANIA DANNY K. DAVIS. ILLINOIS .l.|ERNEY. JOHN F. MASSACHUSETTS JOHN J. DUNCAN. JR.. TENNESSEE WI\,'. LACY CLAY. MISSOURI Tâouse of lßepreøent¡tibes MICHAEL R. TUFNER, OHIO DIANE E. WATSON, CALIFORNIA DAFRELL E. ISSA, CALIFORNIA BRIAN HIGGINS, NEWYORK coMMTTTEEoNovERSTcHTANDGovERNMENTREFoRM l"'ilillTiffilîäÄ;LftÌ"."""^ JOHN A. YARI\,IUTH. KENTUCKY PATFICK T. McHENRY, NORTH CAROLINA BRUCE L. BRALEY. IOWA VIFGINIA FO)C(, NORTH CAROLINA ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON. 2157 Rnveunru House Ornce Butorrue BRIAN P. BILBRAY, CALIFORNIA DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA BILL SALI, IDAHO BETTY MGCOLLUM, MINNESOTA WnsHrrucroru. DC 2051 5-61 43 JIM JORDAN, OHIO JIM COOPER, TENNESSEE CHRIS VAN HOLLEN. MARYLAND MruoBrû (202) 22H051 PAULW. HODES, NEV,/ HAI\¡PSHIRE FÂGrMrE (202) 225-4784 CHRISTOPHER S. MUBPHY, CONNECTICUT MrNoÊrw (202) 22H074 JOHN P. SARBANES, MARYLAND PETÉR WELCH, VEBMONT www.oversight. house.gov January 15,2008 The Honorable Michael B. Mukasey Attorney General U.S. Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW V/ashington, DC 20530 Dear Mr. Attorney General: 'We are writing to ask the Justice Department to investigate whether former Baltimore Orioles baseball player Miguel Tejada made knowingly false material statements to the Committee in connection with the Committee's investigation of former Orioles player Rafael Palmeiro. -

The Baseball Film in Postwar America ALSO by RON BRILEY and from MCFARLAND

The Baseball Film in Postwar America ALSO BY RON BRILEY AND FROM MCFARLAND The Politics of Baseball: Essays on the Pastime and Power at Home and Abroad (2010) Class at Bat, Gender on Deck and Race in the Hole: A Line-up of Essays on Twentieth Century Culture and America’s Game (2003) The Baseball Film in Postwar America A Critical Study, 1948–1962 RON BRILEY McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London All photographs provided by Photofest. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Briley, Ron, 1949– The baseball film in postwar America : a critical study, 1948– 1962 / Ron Briley. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-6123-3 softcover : 50# alkaline paper 1. Baseball films—United States—History and criticism. I. Title. PN1995.9.B28B75 2011 791.43'6579—dc22 2011004853 BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE © 2011 Ron Briley. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. On the cover: center Jackie Robinson in The Jackie Robinson Story, 1950 (Photofest) Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com Table of Contents Preface 1 Introduction: The Post-World War II Consensus and the Baseball Film Genre 9 1. The Babe Ruth Story (1948) and the Myth of American Innocence 17 2. Taming Rosie the Riveter: Take Me Out to the Ball Game (1949) 33 3. -

Table of Contents This Game of Baseball

6/21/2015 The Rules of Play MENU TABLE OF CONTENTS Dividing the deck Taking the Field At-bats Sample Half-Inning 1st Batter Switching and Substituting 2nd Batter 3rd Batter 4th Batter 5th Batter Special Rules The Fan Base Cards Optional Rules Relief Pitchers Pinch Hitters Pinch Runners Base Stealing Bunting Rules Without a Home Summary Why Did I Lose? THIS GAME OF BASEBALL The first thing to do is to divide the deck into two parts: a defensive deck and an offensive deck. The defensive deck consists of these 22 cards: CARD NAME VALUE CARD NAME VALUE The Fan 0 The Force Out 11 The Base Stealer 1 The Suspension 12 The Official Scorer 2 The Showers 13 The Owner 3 Beer 14 The Manager 4 The Bullpen 15 The Commissioner 5 The Bleachers 16 http://gbtango.com/rules/rules.asp 1/23 6/21/2015 The Rules of Play Spring Training 6 The OnDeck Batter 17 The AllStar Break 7 The Night Game 18 The World Series 8 The Doubleheader 19 The Winter Meetings 9 The Umpire 20 The Round Tripper 10 The Ball Girl 21 The remaining 56 cards make up the offensive deck. The offensive cards consist of 4 different suits (Bats, Balls, Gloves and Bases) with 13 cards in each suit (Ace10, Rookie, Veteran, AllStar). In addition, there are 4 special wildcards: The Whiff, The Beanball, The Pickoff and The Circus Catch. Once the cards have been divided into a Defensive and Offensive deck, each part should be briskly shuffled. -

Clips for 7-12-10

MEDIA CLIPS – July 26th, 2018 Blackmon walks it off as Rox hold Astros to 1 hit By Thomas Harding and Anne Rogers MLB.com Jul. 25th, 2018 DENVER -- Standout starting pitching works for the Rockies, eventually -- even when the opponent is the defending World Series champions. And Charlie Blackmon made sure. Jon Gray held the Astros to one hit in seven innings, but had to wait along with the Coors Field crowd of 40,948, until Blackmon's walkoff homer off Collin McHugh with one out in the bottom of the ninth gave the Rockies a 3-2 victory on Wednesday night. It was Blackmon whose 10th-inning error on Tuesday night, his first of the season, opened the door for a six-run rally and an 8-2 Astros victory. This time, Blackmon's 20th homer of the season -- and first career walk-off blast -- pulled the Rockies to 1 1/2 games behind the National League West-leading Dodgers and one game behind the second-place D- backs.. 25th, 2018 "That's the beauty of baseball," Blackmon said. "You can stink, which is OK. As long as you don't stink the next time and the next time. That's what makes baseball great. It's a long season, and we have a chance." The Rockies had lost their previous two games, but have won 16 of their last 21. The two-game split with the Astros, who lead the American League West, came after five straight series wins over teams above .500.25th, 2018 In his second straight standout start since a brief demotion to Triple-A Albuquerque, Gray struck out six and walked two. -

Printer-Friendly Version (PDF)

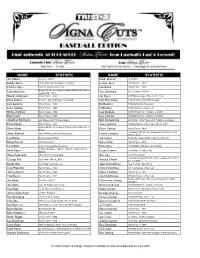

NAME STATISTIC NAME STATISTIC Jim Abbott No-Hitter 9/4/93 Ralph Branca 3x All-Star Bobby Abreu 2005 HR Derby Champion; 2x All-Star George Brett Hall of Fame - 1999 Tommie Agee 1966 AL Rookie of the Year Lou Brock Hall of Fame - 1985 Boston #1 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston Minor Lars Anderson Tom Browning Perfect Game 9/16/88 League Off. P.O.Y. Sparky Anderson Hall of Fame - 2000 Jay Bruce 2007 Minor League Player of the Year Elvis Andrus Texas #1 Overall Prospect -shortstop Tom Brunansky 1985 All-Star; 1987 WS Champion Luis Aparicio Hall of Fame - 1984 Bill Buckner 1980 NL Batting Champion Luke Appling Hall of Fame - 1964 Al Bumbry 1973 AL Rookie of the Year Richie Ashburn Hall of Fame - 1995 Lew Burdette 1957 WS MVP; b. 11/22/26 d. 2/6/07 Earl Averill Hall of Fame - 1975 Ken Caminiti 1996 NL MVP; b. 4/21/63 d. 10/10/04 Jonathan Bachanov Los Angeles AL Pitching prospect Bert Campaneris 6x All-Star; 1st to Player all 9 Positions in a Game Ernie Banks Hall of Fame - 1977 Jose Canseco 1986 AL Rookie of the Year; 1988 AL MVP Boston #4 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston MiLB Daniel Bard Steve Carlton Hall of Fame - 1994 P.O.Y. Philadelphia #1 Overall Prospect-Winning Pitcher '08 Jesse Barfield 1986 All-Star and Home Run Leader Carlos Carrasco Futures Game Len Barker Perfect Game 5/15/81 Joe Carter 5x All-Star; Walk-off HR to win the 1993 WS Marty Barrett 1986 ALCS MVP Gary Carter Hall of Fame - 2003 Tim Battle New York AL Outfield prospect Rico Carty 1970 Batting Champion and All-Star 8x WS Champion; 2 Bronze Stars & 2 Purple Hearts Hank -

Conestoga Valley Little League® Spring

CVLL Conestoga Valley Little League® INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Play Ball! Rules, regulations and other important information for both parents and players GROUPS AND PARTIES Team Rosters Player and coach listings for every team, by age group Field Locations Directions to each of the regularly-used ball fields Thank You Special thanks to all sponsors, supporters and volunteers who help make the season possible Spring 2013 Program Dear Players, Family, and Friends: Welcome to our 22nd year as the Conestoga Valley Little League®. This is my family’s ninth year with CVLL and my second year serving as President. I am pleased to have my own children part of an organization that emphasizes character, team-building, healthy competition, and good clean fun. As we begin a new season, I’m excited about more opportunities to meet new people and develop ball players. Any organization is only as good as the people who run it and I am grateful for the many quality families who play a role in making our league successful. I want to thank all of our CVLL Board Members, Managers, Coaches, Umpires, Team Parents, Field Workers, Business Sponsors and Concession Stand Volunteers who make it all happen. Without everyone ‘pitching’ in to help, our league could not succeed. I want to express my sincerest appreciation to everyone who sacrifices a portion of their time to help. Please stay connected with your child’s coach and our website to learn how you can be of assistance with the needs of CVLL. I encourage you to observe the sponsors listed in the program booklet. -

Baseball All-Time Stars Rosters

BASEBALL ALL-TIME STARS ROSTERS (Boston-Milwaukee) ATLANTA Year Avg. HR CHICAGO Year Avg. HR CINCINNATI Year Avg. HR Hank Aaron 1959 .355 39 Ernie Banks 1958 .313 47 Ed Bailey 1956 .300 28 Joe Adcock 1956 .291 38 Phil Cavarretta 1945 .355 6 Johnny Bench 1970 .293 45 Felipe Alou 1966 .327 31 Kiki Cuyler 1930 .355 13 Dave Concepcion 1978 .301 6 Dave Bancroft 1925 .319 2 Jody Davis 1983 .271 24 Eric Davis 1987 .293 37 Wally Berger 1930 .310 38 Frank Demaree 1936 .350 16 Adam Dunn 2004 .266 46 Jeff Blauser 1997 .308 17 Shawon Dunston 1995 .296 14 George Foster 1977 .320 52 Rico Carty 1970 .366 25 Johnny Evers 1912 .341 1 Ken Griffey, Sr. 1976 .336 6 Hugh Duffy 1894 .440 18 Mark Grace 1995 .326 16 Ted Kluszewski 1954 .326 49 Darrell Evans 1973 .281 41 Gabby Hartnett 1930 .339 37 Barry Larkin 1996 .298 33 Rafael Furcal 2003 .292 15 Billy Herman 1936 .334 5 Ernie Lombardi 1938 .342 19 Ralph Garr 1974 .353 11 Johnny Kling 1903 .297 3 Lee May 1969 .278 38 Andruw Jones 2005 .263 51 Derrek Lee 2005 .335 46 Frank McCormick 1939 .332 18 Chipper Jones 1999 .319 45 Aramis Ramirez 2004 .318 36 Joe Morgan 1976 .320 27 Javier Lopez 2003 .328 43 Ryne Sandberg 1990 .306 40 Tony Perez 1970 .317 40 Eddie Mathews 1959 .306 46 Ron Santo 1964 .313 30 Brandon Phillips 2007 .288 30 Brian McCann 2006 .333 24 Hank Sauer 1954 .288 41 Vada Pinson 1963 .313 22 Fred McGriff 1994 .318 34 Sammy Sosa 2001 .328 64 Frank Robinson 1962 .342 39 Felix Millan 1970 .310 2 Riggs Stephenson 1929 .362 17 Pete Rose 1969 .348 16 Dale Murphy 1987 .295 44 Billy Williams 1970 .322 42