Carriers in a Common Cause 74 1970

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Twig of the Branch Branch 1477 West Coast Florida Letter Carriers

The Twig of the Branch Branch 1477 West Coast Florida Letter Carriers Serving: St. Petersburg — Largo — Dunedin — Pinellas Park — Indian Rocks Beach Punta Gorda — Englewood— Bradenton Beach — Palmetto — Ellenton VOLUME 604 VOICE OF BRANCH 1477 March, 2020 Inside This Issue: PRESIDENT’S REPORT By President Joe Henschen President’s Report 1-2 by Joe Henschen Twitter @ JaHe1 St. Pete Grand Prix 2 MDA Annual Golf Outing 3 This month is dedicated to the members of Branch 36 who on March 17, Entry Form 1970, voted to walk off the job, then backed it up. Executive Vice President 4-5 article—Hubble’s Troubles On Saturday March 21, 2020 at the Manhattan Center, 311 W. 34th Street by Chris Hubble New York NY 1000 where the vote took place the NALC will Vice President 5 commemorate the Wildcat Strike of 1970 and honor the heroes who went by Zulma Betancourt out on strike. Editor’s Corner 5-7 th by Judy Dorris Celebrating the 50 anniversary of the walkout in New York City Last Punch Retiree 7 It can be difficult for letter carriers to understand what it was like for our Minutes of the Branch 7-9 brethren to have launched, at 12:01 a.m. on March 18, 1970, what is now by Recording/Financial Secretary called the Great Postal Strike. Today, we are guaranteed a decent wage Ken Grasso and benefits, are protected from management abuses, and are Sergeant at Arms 9 represented by a strong union. But it wasn’t always like that. by Clay Hansen Auxiliary 181 News 9 Letter carriers in the late 1960s were poorly paid and denied collective by Dottie Tutt-Hutchinson bargaining rights. -

Extensions of Remarks

April 26, 1990 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 8535 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS BENEFITS OF AUTOMATION First-class mail delivery performance was "The mail is not coming in here so we ELUDE POSTAL SERVICE at a five-year low last year, and complaints have to slow down," to avoid looking idle, about late mail rose last summer by 35 per said C. J. Roux, a postal clerk. "We don't cent, despite a sluggish 1 percent growth in want to work ourselves out of a job." HON. NEWT GINGRICH mall volume. The transfer infuriated some longtime OF GEORGIA Automation was to be the service's hope employees, who had thought that they IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES for a turnaround. But efforts to automate would be protected in desirable jobs because have been plagued by poor management and of their seniority. Thursday, April 26, 1990 planning, costly changes of direction, inter "They shuffled me away like an old piece Mr. GINGRICH. Mr. Speaker, as we look at nal scandal and an inability to achieve the of furniture," said Alvin Coulon, a 27-year the Postal Service's proposals to raise rates paramount goal of moving the mall with veteran of the post office and one of those and cut services, I would encourage my col fewer people. transferred to the midnight shift in New Or With 822 new sorting machines like the leans. "No body knew nothing" about the leagues to read the attached article from the one in New Orleans installed across the Washington Post on the problems of innova change. "Nobody can do nothing about it," country in the last two years, the post of he said. -

Locality Pay

Locality Pay February 7, 2014 Report Number: RARC-WP-14-008 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Locality Pay The ongoing debate about the Highlights comparability of postal employee wages to their counterparts in the private sector has Unlike most national employers, the rarely included discussion of one key Postal Service does not adjust wages to element of the U.S. Postal Service’s wage reflect local pay rates or cost-of-living structure. Private sector companies differences. commonly pay employees based on the local cost-of-living and labor market The rest of the federal government conditions. As a result, it is well understood offers “locality pay” — adjusting pay that someone working in Manhattan, New based on local or regional labor York will earn more than someone with an markets. identical job in Manhattan, Kansas. The The Postal Service spends over $30 federal government recognizes this notion billion per year on salaries, so how through well-established locality pay those salaries are distributed across systems for both its white-collar and blue- regions is an important issue. collar workers. In fact, the federal government was already recognizing the The Postal Service should consider importance and necessity of offering locality pay as a means of instituting a wages based on local conditions at least more fair system that could save as early as the Civil War. expenses in some areas and enhance the quality and stability of its workforce The Postal Service, however, does not pay in others. employees based on local labor market Implementing locality pay would be conditions. Despite vast regional challenging, but not impossible, and the differences in labor markets and costs of benefits could be significant. -

Bob· Chester: Trotskyist Leader & Educator by Ed Harris American Workers Party, Led by A.J

JULY 18, 1975 25 CENTS VOLUME 39/NUMBER 27 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE SIOD discriminatory IBVOIIS! LABOR UPSURGE IN ARGENTINA CABINET RESIGNS AS GOVERNMENT IS ROCKED BY MASSIVE STRIKES. PAGE 5. PINE RIDGE I IS BEHIND FBI INVASION: TWO YEARS OF GOVERNMENT TERROR .. PAGE 16. lEW YORK UNION LEADERS RETREAT ON Militant/Mary Scully FIGHT FOR JOBS. PAGE 3. Workers rally in Lisbon. Is Armed Forces Movement leading struggle for socialism? See page 14. WOMEN UN MEETING SHOWS IMPACT OF FEMINIST STRUGGLE. PAGE 9. liNGS. L.A. COPS COVER UP RIGHT WING CAMPAIGN. PAGE 18. 7II In Brief THIS UNCOMMON CAUSE: The Militant has been reporting front of Japan; and if Japan were directly exposed and WEEK'S how Common Cause chief John Gardner has been going to threatened," Helms said, "her intricate economy bat for the two-party system. The Washington Star recently interwoven so closely with the needs and stability ·of the MILITANT asked him if he didn't think that this was a strange cause Western economies-would collapse." for the so-called People's Lobby to embrace "when many 3 Union leaders retreat voters are expressing no confidence in either the Democratic GAY RIGHTS GAIN: The U.S. Civil Service Commission from jobs fight or Republican parties." The question referred to the has backed off from its policy of excluding homosexuals 4 AFSCME ends Pa. strike Common Cause-promoted public election financing law, f~om government jobs. Newly issued guidelines state that with few gains · which provides tax money to the Democrats and Republi court.decisions and injunctions require "the same standard cans, and excludes smaller parties. -

EA Baker Union Update

E.A. Baker Union Update ARVIN AVENAL BAKERSFIELD BORON CALIFORNIA CITY DELANO EDWARDS AFB LAMONT McFARLAND MOJAVE RIDGECREST SHAFTER TAFT TEHACHAPI TRONA WASCO CHARTERED FEBRUARY 25, 1901 Web Version AUGUST 2014 Philadelphia was an amazing experience which required a lot of energy and dedication by your Branch delegates! There are resolutions that are made from various branches across the country that Johnny are heard, debated, then voted on by your delegates. The “theme” this year was CCA’s. The CCA topic dominated most of the resolutions made. There were resolutions approved to negotiate for: CCA Sunday premium; Allow on CCA’s to carry over the maximum amount of annual leave currently 440 hours; Including CCA’s to be eligible employees to receive military pay; Allowing CCA’s to put in for mutual exchanges with other CCA’s; Allow Article 25 to ap- the ply to CCA’s for bargaining unit work (T-6 details). Please remember that these are resolutions. These are requests the membership is telling National we want them to bargain for, we still have to negotiate with Spot Postal management to get them resolved. Postmaster Donohoe is back again with his shrink to survive ideas. He now claims he has the author- ity to slow down delivery standards and thus is The 69th NALC Biannual Convention was moving forward with a plan to close 82 processing held in Philadelphia, PA from July 21st thru plants. One of those 82 is our very own Bakers- July 25, 2014. Branch 782 sent nine del- field facility. No big deal right its only clerks jobs. -

Monitoring Report I=Interview; GR=Graphic; PC=Press Conference; R=Reader; SI=Studio Interview; T=Teaser; TZ=Teased Segment; V=Visual

Monitoring Report I=Interview; GR=Graphic; PC=Press Conference; R=Reader; SI=Studio Interview; T=Teaser; TZ=Teased Segment; V=Visual CDC 09/11 to 11/01 1. Nightline ABC Network National 10/12/2001 11:35 - 12:05 am Estimated Audience: 4,997,900 15.37 TZ; More Terrorism. They continue their discussion about anthrax and bioterrorism. SI; Dr. Jeffrey Koplan, CDC Director, says they received a call from the New York City Health Department involving the NBC employee. Koplan says the woman was exposed to the contents of an ill intentioned letter and developed a skin rash and lesion. Koplan says the amount of powder matters when trying to determine if it is anthrax. Koplan says the health agencies have a done a good job in determining the cases quickly. Koplan says there is no reason for anyone to get a nasal swab at this time. 21.42 2. Good Morning America ABC Network National 10/15/2001 7:00 - 8:00 am Estimated Audience: 4,660,780 08.23 TZ; Anthrax. America was preparing for an anthrax attack. Everybody at NBC wants to be tested. SI; Dr. Stephen Ostroff, CDC, says we know that anthrax doesn't widely disperse itself. Ostroff says they've been very precautionary, gathering info & testing everybody that was on the floor where the letter may have been present. GR; Photos of anthrax cases. GR; Inhalation Anthrax. 13.04 3. Good Morning America ABC Network National 10/16/2001 7:00 - 8:00 am Estimated Audience: 4,660,780 14.50 TZ; Anthrax Analysis. -

The 1970 Postal Strike and Labor's Decline

i COLLECTIVE BICKERING: THE 1970 POSTAL STRIKE AND LABOR’S DECLINE ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Fullerton ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Public History ____________________________________ By Matthew Franklin Thesis Committee Approval: Alison Varzally, Department of History, Chair Volker Janssen, Department of History Carrie Lane, Department of American Studies Spring, 2018 ABSTRACT The 1970 Postal Strike, beyond being the largest wildcat strike in U.S. history, served as an important milestone in the decline of the American labor movement in the second half of the twentieth century. The events of the strike, the rank-and-file’s reasons behind the demonstration, and their leadership’s response revealed the major flaws and problems that kept unions from maintaining their power after the 1960s: members’ feelings of disrespect from union leaders, said leaders’ unwillingness to adapt to the changing times, and a president and congress that focused less on mutual cooperation and more on “trimming the fat” of government spending. Although postal employees succeeded in gaining pay raises and numerous benefits, the lack of meaningful reform and union democratization failed to correct many of the major issues that caused the strike in the first place. The decades following the postal strike show a series of events that confirm 1970 as the start of a national trend toward a more austere political and economic atmosphere—and a sign that American labor as a single entity could not adapt to this change. This failure to adapt allowed anti-union elements within the government to turn public opinion against organized labor and further speed its decline. -

NALC and Organized Labor Succeed in Obtaining Critical Improvements

Rolando Urges NALC Membership To Give to Haiti Earthquake Relief One of the greatest natural disasters in history has devastated the Caribbean island nation of Haiti and the people there are in desperate need. January 15, 2010 No. 10-01 NALC President Fred Rolando noted that while the extent of the loss of life, injuries and total destruction in Haiti is unknown, it surely will be of unbelievable magnitude, surpassing Hurricane Katrina, possibly the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, and potentially be among the highest death tolls ever. “As help rushes from this country to our nearby NALC and Organized Labor Succeed neighbor, our thoughts and prayers go out to all who have died, suffered injury or seen their lives shaken to the core by this horrific earthquake,” Rolando said. In Obtaining Critical Improvements “Letter carriers have a great tradition of helping those in need, and now I ask that you join me in making a commitment of hope to these victims by sending a To Congressional Health Reform Bill generous charitable donation.” USGS Map Those interested in providing volunteer personal assistance should contact the Center for International Disaster Information at www.cidi.org and (703) 276- Rolando Says Legislation Moving Through Congress 1914. The AFL-CIO has identified several charitable organizations that are providing aid to Haiti. Provides ‘Significant Progress’ for American Workers Donations may be made to: The NALC and much of the labor movement, led by AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka, have been ● American Red Cross International Response Fund: www.redcross.org, or toll-free at successful in negotiating an agreement with the Obama administration and congressional leaders to 1-800-REDCROSS. -

Remembering the Great Postal Strike His Year, As Congress Once Again Up

News Remembering the Great Postal Strike his year, as Congress once again up. Court injunctions ordering considers the future of the Postal the strikers to return to work were TService, letter carriers are looking issued, and ignored. The strike back to the Great Postal Strike of 47 spread throughout the New York years ago for inspiration. City area. Thousands of clerks, “The letter carriers who risked so drivers and other postal employees much to stand up for their rights knew refused to cross picket lines, effec- that they had to stick together,” NALC tively joining the strike. President Fredric Rolando said. “In President Richard Nixon or- New York, when the first group voted dered 25,000 National Guard sol- to strike, they didn’t all go to the room diers to case and carry the mail. agreeing on their course of action. But The only thing this accomplished, they all left the room ready to act as however, was to strengthen the one. That’s the power of a union.” hand of letter carriers. Try as In 1970, letter carriers had minimal they might, the National Guards- collective-bargaining rights restricted to men weren’t ready to step in and local issues. Pay, benefits and working perform letter carrier duties. The conditions lagged behind much of the mail piled up higher, and mail Congress acted quickly to reorganize rest of the workforce—some carriers that did reach mailboxes often ended the Post Office into a new, self-sustain- even qualified for welfare. Pushed to up in the wrong ones. ing U.S. -

NALC Looks Back at the 1970 Postal Strike

NALC looks back at the 1970 postal strike his year, as the nation once again considers a week after the future of the Postal Service and the the first letter Tletter carrier profession, letter carriers are carriers walked looking back to the Great Postal Strike of 42 out, branches in years ago for inspiration. several other “The letter carriers who risked so much to cities had voted stand up for their rights knew that they had to to join them. By stick together,” said NALC President Fredric March 23, thou- Rolando. “In New York, when the first group sands more letter voted to strike, they didn’t all go in the room carriers nationwide agreeing on their course of action. But they all had joined the strike left the room ready to act as one. That’s the or were poised to. power of a union.” The Post Office In 1970, letter carriers had minimal collective- Department negoti- bargaining rights restricted to local issues. Pay, ated with the union benefits and working conditions lagged behind throughout the strike, the rest of the workforce—some carriers even and when it seemed qualified for welfare. Pushed to the limit, carriers a breakthrough was at New York Branch 36 voted on March 17, 1970, likely, the letter carriers to walk off the job. One of their leaders, who held put down their signs and no official office in the branch at the time, was a returned to work. It had letter carrier named Vincent Sombrotto, who taken only a week, and a would later become president of NALC. -

The Great Postal Strike Celebrating the 50Th Anniversary

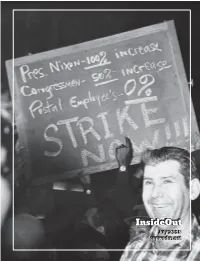

THE GREAT POSTAL STRIKE CELEBRATING THE 50TH hortly after midnight on a chilly March 18, 1970, New York ANNIVERSARY City Branch 36 letter carriers moved police sawhorses left over from the recent St. Patrick’s Day parade into position along the 45th Street side of the Grand Central post office and started picketing. By 1 a.m., the 51st Street police station reported that 30 picketers were there. An hour later, police reported 15 picketers outside the Murray Hill Station at 205 East 33rd St. What would become known as the Great Postal Strike—an illegal wildcat strike that threatened the jobs, pensions and even freedom of scores of America’s mail carriers—had just begun. With letter carriers and other postal workers on duty at 12:01 a.m. in Manhat- tan and the Bronx, news of the work stoppage spread quickly. Almost immediate- ly, more than 25,000 postal clerks and drivers—members of the giant Manhattan- Bronx Postal Union (MBPU)—agreed to honor the picket lines and refused to go to work, bringing postal operations to a halt. By the time the morning commute was under way, radio and newspapers throughout the city were reporting lines with hundreds of picketers. What had begun in Manhattan was spreading throughout New York City’s other boroughs— Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx and Staten Island—as well as Long Island and por- tions of upstate New York, and into New Jersey and Connecticut. Those first strikers had been afraid that no one would join them, and that the strike would quickly be put down. -

Insideout July 2018 Cupwedm.Net

InsideOut July 2018 cupwedm.net July 2018// Inside Out // 1 InsideOut July 2018// Empower // Organize // Resist Contents InsideOut is the monthly publication 4. Photo Submission // Cheryl Chow of the Edmonton Local of CUPW. The 5. President’s Report // Nancy Dodsworth main purpose of this paper is to educate and inform members of the activities 6. The Rules of Engagement // Aaron Taylor of and opportunities in their union, as 7. Organize. Empower. Resist. // Roland Schmidt well as raise awareness of anything else 13. Summary of Arbitrator Flynn’s Decision pertaining to the labour movement. on RSMC Pay Equity // RSMC Pay Equity Opinions expressed are those of the Committee author and not necessarily the official 14. No Longer a “Competitive Advantage” // views of the Local. RSMC Pay Equity Committee The InsideOut Committee is always 15. CPC Still Has “No Position” on RSMC Pay Equity Issues // RSMC Pay Equity interested in submissions of original Committee articles, photographs, or illustrations 16. Summer - Time to Reach Out to Our to be considered for publication in our Communities // Mike Palacek next issue. Prospective material should 17. Authority Meant Nothing: A Foreword // always concern CUPW or the labour Kyle Turner movement. 18. Paul Prescod Submissions should be e-mailed When the Mailmen Rebelled // to the Editor no later than the 15th of 21. In My View // Andie Wirsch each month. 22. No Relief // Kyle Turner Kyle Turner, Editor 23. From the Grievance Office //Carl Hentzelt [email protected] Contact CUPW Edmonton Phone: (780) 423-9000 Toll-free: 1-877-423-CUPW (2879) Fax: (780) 423-2883 Visit us at the office at 18121 107 Ave, Edmonton, AB T5S 1K4 or online at www.cupwedm.net Our office hours are Monday through Friday from 8 am until 5 pm.