University Microfilms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Xian, Qiao-Shuang, "Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études"" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2432. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2432 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. REDISCOVERING FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN’S TROIS NOUVELLES ÉTUDES A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Qiao-Shuang Xian B.M., Columbus State University, 1996 M.M., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF EXAMPLES ………………………………………………………………………. iii LIST OF FIGURES …………………………………………………………………………… v ABSTRACT …………………………………………………………………………………… vi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………….. 1 The Rise of Piano Methods …………………………………………………………….. 1 The Méthode des Méthodes de piano of 1840 -

The Form of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2011 The orF m of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites Daniel E. Prindle University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Part of the Composition Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Prindle, Daniel E., "The orF m of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites" (2011). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 636. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/636 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FORM OF THE PRELUDES TO BACH’S UNACCOMPANIED CELLO SUITES A Thesis Presented by DANIEL E. PRINDLE Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2011 Master of Music in Music Theory © Copyright by Daniel E. Prindle 2011 All Rights Reserved ii THE FORM OF THE PRELUDES TO BACH’S UNACCOMPANIED CELLO SUITES A Thesis Presented by DANIEL E. PRINDLE Approved as to style and content by: _____________________________________ Gary Karpinski, Chair _____________________________________ Miriam Whaples, Member _____________________________________ Brent Auerbach, Member ___________________________________ Jeffrey Cox, Department Head Department of Music and Dance iii DEDICATION To Michelle and Rhys. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to acknowledge the generous sacrifice made by my family. -

For Two Flutes

Wilhelm Friedemann BACH Duets for Two Flutes Patrick Gallois Kazunori Seo Wilhelm Friedemann Bach (1710–1784) Sonatas has been the object of some speculation.1 It has two-part writing, its rapid outer movements framing a C Six Duets for Two Flutes, F.54–59 been suggested that the Duets in E minor, F.54 and G major, minor Adagio. The Duet in F major, F.57, has at its heart a F.59 may be relatively early works, dating from 1729 or D minor Cantabile, the two parts intricately interwoven, with Born in Weimar in 1710, Wilhelm Friedemann Bach was the Sebastian had abandoned what had been, until his patron’s perhaps from his first years in Dresden. The Duets in E flat a rapid final movement. The demands for virtuosity suggest eldest son of Johann Sebastian Bach by his first wife, Maria marriage, a happy position at court for employment under major, F.55 and F major, F.57 may have been written before the influence of distinguished flautists in Dresden, Pierre- Barbara. When his father moved to Cöthen in 1717 as Court the city council in Leipzig, so his son left the court society of 1741, a date suggested by the use made of extracts for his Gabriel Buffardin, the teacher of Quantz, who was employed Kapellmeister to the young Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen, Dresden for municipal employment in Halle, the birth-place Solfeggi by Quantz, who was then employed by Frederick for many years at the court of the Elector of Saxony and, Wilhelm Friedemann presumably studied at the Lutheran of Handel, who had briefly served as organist there. -

Many of Us Are Familiar with Popular Major Chord Progressions Like I–IV–V–I

Many of us are familiar with popular major chord progressions like I–IV–V–I. Now it’s time to delve into the exciting world of minor chords. Minor scales give flavor and emotion to a song, adding a level of musical depth that can make a mediocre song moving and distinct from others. Because so many of our favorite songs are in major keys, those that are in minor keys1 can stand out, and some musical styles like rock or jazz thrive on complex minor scales and harmonic wizardry. Minor chord progressions generally contain richer harmonic possibilities than the typical major progressions. Minor key songs frequently modulate to major and back to minor. Sometimes the same chord can appear as major and minor in the very same song! But this heady harmonic mix is nothing to be afraid of. By the end of this article, you’ll not only understand how minor chords are made, but you’ll know some common minor chord progressions, how to write them, and how to use them in your own music. With enough listening practice, you’ll be able to recognize minor chord progressions in songs almost instantly! Table of Contents: 1. A Tale of Two Tonalities 2. Major or Minor? 3. Chords in Minor Scales 4. The Top 3 Chords in Minor Progressions 5. Exercises in Minor 6. Writing Your Own Minor Chord Progressions 7. Your Minor Journey 1 https://www.musical-u.com/learn/the-ultimate-guide-to-minor-keys A Tale of Two Tonalities Western music is dominated by two tonalities: major and minor. -

To Read Or Download the Competition Program Guide

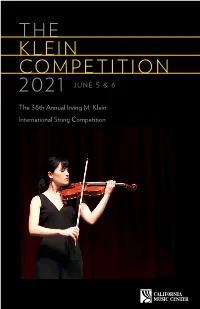

THE KLEIN COMPETITION 2021 JUNE 5 & 6 The 36th Annual Irving M. Klein International String Competition TABLE OF CONTENTS Board of Directors Dexter Lowry, President Katherine Cass, Vice President Lian Ophir, Treasurer Ruth Short, Secretary Susan Bates Richard Festinger Peter Gelfand 2 4 5 Kevin Jim Mitchell Sardou Klein Welcome The Visionary The Prizes Tessa Lark Stephanie Leung Marcy Straw, ex officio Lee-Lan Yip Board Emerita 6 7 8 Judith Preves Anderson The Judges/Judging The Mentor Commissioned Works 9 10 11 Competition Format Past Winners About California Music Center Marcy Straw, Executive Director Mitchell Sardou Klein, Artistic Director for the Klein Competition 12 18 22 californiamusiccenter.org [email protected] Artist Programs Artist Biographies Donor Appreciation 415.252.1122 On the cover: 21 25 violinist Gabrielle Després, First Prize winner 2020 In Memory Upcoming Performances On this page: cellist Jiaxun Yao, Second Prize winner 2020 WELCOME WELCOME Welcome to the 36th Annual This year’s distinguished jury includes: Charles Castleman (active violin Irving M. Klein International performer/pedagogue and professor at the University of Miami), Glenn String Competition! This is Dicterow (former New York Philharmonic concertmaster and faculty the second, and we hope the member at the USC Thornton School of Music), Karen Dreyfus (violist, last virtual Klein Competition Associate Professor at the USC Thornton School of Music and the weekend. We have every Manhattan School of Music), our composer, Sakari Dixon Vanderveer, expectation that next June Daniel Stewart (Music Director of the Santa Cruz Symphony and Wattis we will be back live, with Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra), Ian our devoted audience in Swensen (Chair of the Violin Faculty at the San Francisco Conservatory attendance, at the San of Music), and Barbara Day Turner (Music Director of the San José Francisco Conservatory. -

Extended Program Notes for a Thesis Recital Miroslav Daciċ Florida International University

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-25-2011 Extended program notes for a thesis recital Miroslav Daciċ Florida International University DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI14061583 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Daciċ, Miroslav, "Extended program notes for a thesis recital" (2011). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2485. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/2485 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida EXTENDED PROGRAM NOTES FOR A THESIS RECITAL A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC by Miroslav Dacic 2011 To: Dean Brian Schriner College of Architecture and the Arts This thesis, written by Miroslav Dacic, and entitled Extended Program Notes for a Thesis Recital, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. Joel Galand Jose Lopez Kemal Gekic, Major Professor Date of Defense: March 25, 2011 The thesis of Miroslav Dacic is approved. Dean Brian Schriner College of Architecture and the Arts Interim Dean Kevin O'Shea University Graduate School Florida International University~ 2011 • • 11 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS EXTENDED PROGRAM NOTES FOR A THESIS RECITAL by Miroslav Dacic Florida International University, 2011 Miami, Florida Professor Kemal Gekic, Major Professor The purpose of this thesis recital is to focus on an integral perforn1ance of Chopin's op.28 prelude cycle which consists of a CD of the recital and an analytical paper on the set. -

Wilhelm Friedemann Bach

Wilhelm Friedemann Bach COMPLETE ORGAN MUSIC Filippo Turri Wilhelm Friedemann Bach 1710-1784 The first son of Johann Sebastian and Maria Barbara Bach, Wilhelm Friedemann Complete Organ Music Bach (Weimar, 22 November 1710 – Berlin, 1 July 1784) lived a life that in many respects would fit in perfectly with the biography of a tormented artist of the Drei dreistimmigen Fugen Sieben Choralvorspiele F.38 romantic age. He studied under his father, showing early talent as an instrumentalist Three 3-part Fugues Seven Chorale Preludes F.38 (organist, harpsichordist, violinist) and composer, as well as considerable gifts as 1. Fugue in B flat F.34 2’56 15. I. Nun komm der a mathematician. Given his father’s Pythagorean passions, this latter aptitude is 2. Fugue in F F.33 5’22 Heiden Heiland 1’46 not really as surprising at it might at first seem, yet it is certainly true that Wilhelm 3. Fugue in C minor F.32 6’38 16. II. Christe, der du bist Tag Friedemann was versatile and his interests widespread. At the early age of 23 he was und Licht 2’15 appointed principal organist at the church of St. Sophia in Dresden, and in 1747 Acht dreistimmigen Fugen für Orgel 17. III. Jesu, meine Freude 3’59 became Musikdirektor and organist at the Church of Our Lady in Halle. On account oder Clavier F.31 18. IV. Durch Adams Fall is of his years in Halle, where he married Dorothea Elisabeth Georgi (1721-1791), he is Eight 3-part fugues for Organ ganz verderbt 3’35 often referred to as the “Halle” Bach. -

Rachmaninoff's Early Piano Works and the Traces of Chopin's Influence

Rachmaninoff’s Early Piano works and the Traces of Chopin’s Influence: The Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 & The Moments Musicaux, Op.16 A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Division of Keyboard Studies of the College-Conservatory of Music by Sanghie Lee P.D., Indiana University, 2011 B.M., M.M., Yonsei University, Korea, 2007 Committee Chair: Jonathan Kregor, Ph.D. Abstract This document examines two of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s early piano works, Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 (1892) and Moments Musicaux, Opus 16 (1896), as they relate to the piano works of Frédéric Chopin. The five short pieces that comprise Morceaux de Fantaisie and the six Moments Musicaux are reminiscent of many of Chopin’s piano works; even as the sets broadly build on his character genres such as the nocturne, barcarolle, etude, prelude, waltz, and berceuse, they also frequently are modeled on or reference specific Chopin pieces. This document identifies how Rachmaninoff’s sets specifically and generally show the influence of Chopin’s style and works, while exploring how Rachmaninoff used Chopin’s models to create and present his unique compositional identity. Through this investigation, performers can better understand Chopin’s influence on Rachmaninoff’s piano works, and therefore improve their interpretations of his music. ii Copyright © 2018 by Sanghie Lee All rights reserved iii Acknowledgements I cannot express my heartfelt gratitude enough to my dear teacher James Tocco, who gave me devoted guidance and inspirational teaching for years. -

The Devil's Interval by Jerry Tachoir

Sound Enhanced Hear the music example in the Members Only section of the PAS Web site at www.pas.org The Devil’s Interval BY JERRY TACHOIR he natural progression from consonance to dissonance and ii7 chords. In other words, Dm7 to G7 can now be A-flat m7 to resolution helps make music interesting and satisfying. G7, and both can resolve to either a C or a G-flat. Using the TMusic would be extremely bland without the use of disso- other dominant chord, D-flat (with the basic ii7 to V7 of A-flat nance. Imagine a world of parallel thirds and sixths and no dis- m7 to D-flat 7), we can substitute the other relative ii7 chord, sonance/resolution. creating the progression Dm7 to D-flat 7 which, again, can re- The prime interval requiring resolution is the tritone—an solve to either a C or a G-flat. augmented 4th or diminished 5th. Known in the early church Here are all the possibilities (Note: enharmonic spellings as the “Devil’s interval,” tritones were actually prohibited in of- were used to simplify the spelling of some chords—e.g., B in- ficial church music. Imagine Bach’s struggle to take music stead of C-flat): through its normal progression of tonic, subdominant, domi- nant, and back to tonic without the use of this interval. Dm7 G7 C Dm7 G7 Gb The tritone is the characteristic interval of all dominant bw chords, created by the “guide tones,” or the 3rd and 7th. The 4 ˙ ˙ w ˙ ˙ tritone interval can be resolved in two types of contrary motion: &4˙ ˙ w ˙ ˙ bbw one in which both notes move in by half steps, and one in which ˙ ˙ w ˙ ˙ b w both notes move out by half steps. -

Major and Minor Scales Half and Whole Steps

Dr. Barbara Murphy University of Tennessee School of Music MAJOR AND MINOR SCALES HALF AND WHOLE STEPS: half-step - two keys (and therefore notes/pitches) that are adjacent on the piano keyboard whole-step - two keys (and therefore notes/pitches) that have another key in between chromatic half-step -- a half step written as two of the same note with different accidentals (e.g., F-F#) diatonic half-step -- a half step that uses two different note names (e.g., F#-G) chromatic half step diatonic half step SCALES: A scale is a stepwise arrangement of notes/pitches contained within an octave. Major and minor scales contain seven notes or scale degrees. A scale degree is designated by an Arabic numeral with a cap (^) which indicate the position of the note within the scale. Each scale degree has a name and solfege syllable: SCALE DEGREE NAME SOLFEGE 1 tonic do 2 supertonic re 3 mediant mi 4 subdominant fa 5 dominant sol 6 submediant la 7 leading tone ti MAJOR SCALES: A major scale is a scale that has half steps (H) between scale degrees 3-4 and 7-8 and whole steps between all other pairs of notes. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 W W H W W W H TETRACHORDS: A tetrachord is a group of four notes in a scale. There are two tetrachords in the major scale, each with the same order half- and whole-steps (W-W-H). Therefore, a tetrachord consisting of W-W-H can be the top tetrachord or the bottom tetrachord of a major scale. -

Boris's Bells, by Way of Schubert and Others

Boris's Bells, By Way of Schubert and Others Mark DeVoto We define "bell chords" as different dominant-seventh chords whose roots are separated by multiples of interval 3, the minor third. The sobriquet derives from the most famous such pair of harmonies, the alternating D7 and AI? that constitute the entire harmonic substance of the first thirty-eight measures of scene 2 of the Prologue in Musorgsky's opera Boris Godunov (1874) (example O. Example 1: Paradigm of the Boris Godunov bell succession: AJ,7-D7. A~7 D7 '~~&gl n'IO D>: y 7 G: y7 The Boris bell chords are an early milestone in the history of nonfunctional harmony; yet the two harmonies, considered individually, are ofcourse abso lutely functional in classical contexts. This essay traces some ofthe historical antecedents of the bell chords as well as their developing descendants. Dominant Harmony The dominant-seventh chord is rightly recognized as the most unambiguous of the essential tonal resources in classical harmonic progression, and the V7-1 progression is the strongest means of moving harmony forward in immediate musical time. To put it another way, the expectation of tonic harmony to follow a dominant-seventh sonority is a principal component of forehearing; we assume, in our ordinary and long-tested experience oftonal music, that the tonic function will follow the dominant-seventh function and be fortified by it. So familiar is this everyday phenomenon that it hardly needs to be stated; we need mention it here only to assert the contrary case, namely, that the dominant-seventh function followed by something else introduces the element of the unexpected. -

The Use of the Polish Folk Music Elements and the Fantasy Elements in the Polish Fantasy on Original Themes In

THE USE OF THE POLISH FOLK MUSIC ELEMENTS AND THE FANTASY ELEMENTS IN THE POLISH FANTASY ON ORIGINAL THEMES IN G-SHARP MINOR FOR PIANO AND ORCHESTRA OPUS 19 BY IGNACY JAN PADEREWSKI Yun Jung Choi, B.A., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Adam Wodnicki, Major Professor Jeffrey Snider, Minor Professor Joseph Banowetz, Committee Member Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Choi, Yun Jung, The Use of the Polish Folk Music Elements and the Fantasy Elements in the Polish Fantasy on Original Themes in G-sharp Minor for Piano and Orchestra, Opus 19 by Ignacy Jan Paderewski. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2007, 105 pp., 5 tables, 65 examples, references, 97 titles. The primary purpose of this study is to address performance issues in the Polish Fantasy, Op. 19, by examining characteristics of Polish folk dances and how they are incorporated in this unique work by Paderewski. The study includes a comprehensive history of the fantasy in order to understand how Paderewski used various codified generic aspects of the solo piano fantasy, as well as those of the one-movement concerto introduced by nineteenth-century composers such as Weber and Liszt. Given that the Polish Fantasy, Op. 19, as well as most of Paderewski’s compositions, have been performed more frequently in the last twenty years, an analysis of the combination of the three characteristic aspects of the Polish Fantasy, Op.19 - Polish folk music, the generic rhetoric of a fantasy and the one- movement concerto - would aid scholars and performers alike in better understanding the composition’s engagement with various traditions and how best to make decisions about those traditions when approaching the work in a concert setting.