Notes on the Program Claude Debussy: Preludes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Xian, Qiao-Shuang, "Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études"" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2432. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2432 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. REDISCOVERING FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN’S TROIS NOUVELLES ÉTUDES A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Qiao-Shuang Xian B.M., Columbus State University, 1996 M.M., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF EXAMPLES ………………………………………………………………………. iii LIST OF FIGURES …………………………………………………………………………… v ABSTRACT …………………………………………………………………………………… vi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………….. 1 The Rise of Piano Methods …………………………………………………………….. 1 The Méthode des Méthodes de piano of 1840 -

The Form of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2011 The orF m of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites Daniel E. Prindle University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Part of the Composition Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Prindle, Daniel E., "The orF m of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites" (2011). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 636. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/636 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FORM OF THE PRELUDES TO BACH’S UNACCOMPANIED CELLO SUITES A Thesis Presented by DANIEL E. PRINDLE Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2011 Master of Music in Music Theory © Copyright by Daniel E. Prindle 2011 All Rights Reserved ii THE FORM OF THE PRELUDES TO BACH’S UNACCOMPANIED CELLO SUITES A Thesis Presented by DANIEL E. PRINDLE Approved as to style and content by: _____________________________________ Gary Karpinski, Chair _____________________________________ Miriam Whaples, Member _____________________________________ Brent Auerbach, Member ___________________________________ Jeffrey Cox, Department Head Department of Music and Dance iii DEDICATION To Michelle and Rhys. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to acknowledge the generous sacrifice made by my family. -

Extended Program Notes for a Thesis Recital Miroslav Daciċ Florida International University

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-25-2011 Extended program notes for a thesis recital Miroslav Daciċ Florida International University DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI14061583 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Daciċ, Miroslav, "Extended program notes for a thesis recital" (2011). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2485. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/2485 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida EXTENDED PROGRAM NOTES FOR A THESIS RECITAL A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC by Miroslav Dacic 2011 To: Dean Brian Schriner College of Architecture and the Arts This thesis, written by Miroslav Dacic, and entitled Extended Program Notes for a Thesis Recital, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. Joel Galand Jose Lopez Kemal Gekic, Major Professor Date of Defense: March 25, 2011 The thesis of Miroslav Dacic is approved. Dean Brian Schriner College of Architecture and the Arts Interim Dean Kevin O'Shea University Graduate School Florida International University~ 2011 • • 11 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS EXTENDED PROGRAM NOTES FOR A THESIS RECITAL by Miroslav Dacic Florida International University, 2011 Miami, Florida Professor Kemal Gekic, Major Professor The purpose of this thesis recital is to focus on an integral perforn1ance of Chopin's op.28 prelude cycle which consists of a CD of the recital and an analytical paper on the set. -

Rachmaninoff's Early Piano Works and the Traces of Chopin's Influence

Rachmaninoff’s Early Piano works and the Traces of Chopin’s Influence: The Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 & The Moments Musicaux, Op.16 A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Division of Keyboard Studies of the College-Conservatory of Music by Sanghie Lee P.D., Indiana University, 2011 B.M., M.M., Yonsei University, Korea, 2007 Committee Chair: Jonathan Kregor, Ph.D. Abstract This document examines two of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s early piano works, Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 (1892) and Moments Musicaux, Opus 16 (1896), as they relate to the piano works of Frédéric Chopin. The five short pieces that comprise Morceaux de Fantaisie and the six Moments Musicaux are reminiscent of many of Chopin’s piano works; even as the sets broadly build on his character genres such as the nocturne, barcarolle, etude, prelude, waltz, and berceuse, they also frequently are modeled on or reference specific Chopin pieces. This document identifies how Rachmaninoff’s sets specifically and generally show the influence of Chopin’s style and works, while exploring how Rachmaninoff used Chopin’s models to create and present his unique compositional identity. Through this investigation, performers can better understand Chopin’s influence on Rachmaninoff’s piano works, and therefore improve their interpretations of his music. ii Copyright © 2018 by Sanghie Lee All rights reserved iii Acknowledgements I cannot express my heartfelt gratitude enough to my dear teacher James Tocco, who gave me devoted guidance and inspirational teaching for years. -

The Use of the Polish Folk Music Elements and the Fantasy Elements in the Polish Fantasy on Original Themes In

THE USE OF THE POLISH FOLK MUSIC ELEMENTS AND THE FANTASY ELEMENTS IN THE POLISH FANTASY ON ORIGINAL THEMES IN G-SHARP MINOR FOR PIANO AND ORCHESTRA OPUS 19 BY IGNACY JAN PADEREWSKI Yun Jung Choi, B.A., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Adam Wodnicki, Major Professor Jeffrey Snider, Minor Professor Joseph Banowetz, Committee Member Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Choi, Yun Jung, The Use of the Polish Folk Music Elements and the Fantasy Elements in the Polish Fantasy on Original Themes in G-sharp Minor for Piano and Orchestra, Opus 19 by Ignacy Jan Paderewski. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2007, 105 pp., 5 tables, 65 examples, references, 97 titles. The primary purpose of this study is to address performance issues in the Polish Fantasy, Op. 19, by examining characteristics of Polish folk dances and how they are incorporated in this unique work by Paderewski. The study includes a comprehensive history of the fantasy in order to understand how Paderewski used various codified generic aspects of the solo piano fantasy, as well as those of the one-movement concerto introduced by nineteenth-century composers such as Weber and Liszt. Given that the Polish Fantasy, Op. 19, as well as most of Paderewski’s compositions, have been performed more frequently in the last twenty years, an analysis of the combination of the three characteristic aspects of the Polish Fantasy, Op.19 - Polish folk music, the generic rhetoric of a fantasy and the one- movement concerto - would aid scholars and performers alike in better understanding the composition’s engagement with various traditions and how best to make decisions about those traditions when approaching the work in a concert setting. -

An Annotated Catalogue of the Major Piano Works of Sergei Rachmaninoff Angela Glover

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2003 An Annotated Catalogue of the Major Piano Works of Sergei Rachmaninoff Angela Glover Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MUSIC AN ANNOTATED CATALOGUE OF THE MAJOR PIANO WORKS OF SERGEI RACHMANINOFF By ANGELA GLOVER A Treatise submitted to the School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2003 The members of the Committee approve the treatise of Angela Glover defended on April 8, 2003. ___________________________________ Professor James Streem Professor Directing Treatise ___________________________________ Professor Janice Harsanyi Outside Committee Member ___________________________________ Professor Carolyn Bridger Committee Member ___________________________________ Professor Thomas Wright Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract………………………………………………….............................................. iv INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………. 1 1. MORCEAUX DE FANTAISIE, OP.3…………………………………………….. 3 2. MOMENTS MUSICAUX, OP.16……………………………………………….... 10 3. PRELUDES……………………………………………………………………….. 17 4. ETUDES-TABLEAUX…………………………………………………………… 36 5. SONATAS………………………………………………………………………… 51 6. VARIATIONS…………………………………………………………………….. 58 BIBLIOGRAPHY…………………………………………………………………. -

The Preludes in Chinese Style

The Preludes in Chinese Style: Three Selected Piano Preludes from Ding Shan-de, Chen Ming-zhi and Zhang Shuai to Exemplify the Varieties of Chinese Piano Preludes D.M.A. DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jingbei Li, D.M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2019 D.M.A. Document Committee: Professor Steven M. Glaser, Advisor Dr. Arved Ashby Dr. Edward Bak Copyrighted by Jingbei Li, D.M.A 2019 ABSTRACT The piano was first introduced to China in the early part of the twentieth century. Perhaps as a result of this short history, European-derived styles and techniques influenced Chinese composers in developing their own compositional styles for the piano by combining European compositional forms and techniques with Chinese materials and approaches. In this document, my focus is on Chinese piano preludes and their development. Having performed the complete Debussy Preludes Book II on my final doctoral recital, I became interested in comprehensively exploring the genre for it has been utilized by many Chinese composers. This document will take a close look in the way that three modern Chinese composers have adapted their own compositional styles to the genre. Composers Ding Shan-de, Chen Ming-zhi, and Zhang Shuai, while prominent in their homeland, are relatively unknown outside China. The Three Piano Preludes by Ding Shan-de, The Piano Preludes and Fugues by Chen Ming-zhi and The Three Preludes for Piano by Zhang Shuai are three popular works which exhibit Chinese musical idioms and demonstrate the variety of approaches to the genre of the piano prelude bridging the twentieth century. -

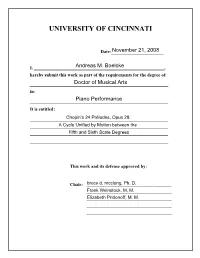

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Chopin’s 24 Préludes, Opus 28: A Cycle Unified by Motion between the Fifth and Sixth Scale Degrees A document submitted to the The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Keyboard Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2008 by Andreas Boelcke B.A., Missouri Western State University in Saint Joseph, 2002 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2005 Committee Chair: bruce d. mcclung, Ph.D. ii ABSTRACT Chopin’s twenty-four Préludes, Op. 28 stand out as revolutionary in history, for they are neither introductions to fugues, nor etude-like exercises as those preludes by other early nineteenth-century composers such as Johann Nepomuk Hummel, Johan Baptist Cramer, Friedrich Kalkbrenner, and Muzio Clementi. Instead they are the first instance of piano preludes as independent character pieces. This study shows, however, that Op. 28 is not just the beginning of the Romantic prelude tradition but forms a coherent large-scale composition unified by motion between the fifths and sixth scale degrees. After an overview of the compositional origins of Chopin’s Op. 28 and an outline of the history of keyboard preludes, the set will be compared to the contemporaneous ones by Hummel, Clementi, and Kalbrenner. The following chapter discusses previous theories of coherence in Chopin’s Préludes, including those by Jósef M. -

Changd75304.Pdf

Copyright by Chia-Lun Chang 2006 The Treatise Committee for Chia-Lun Chang Certifies that this is the approved version of the following treatise: FIVE PRELUDES OPUS 74 BY ALEXANDER SCRIABIN: THE MYSTIC CHORD AS BASIS FOR NEW MEANS OF HARMONIC PROGRESSION Committee: Elliott Antokoletz, Co-Supervisor Lita Guerra, Co-Supervisor Gregory Allen A. David Renner Rebecca A. Baltzer Reshma Babra Naidoo FIVE PRELUDES OPUS 74 BY ALEXANDER SCRIABIN: THE MYSTIC CHORD AS BASIS FOR NEW MEANS OF HARMONIC PROGRESSION by Chia-Lun Chang, B.A., M.M. Treatise Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts The University of Texas at Austin December, 2006 Dedication To Mom and Dad Acknowledgements I wish to express my sincere gratitude to my academic supervisor, Professor Elliott Antokoletz, for his intelligence, unfailing energy and his inexhaustible patience. This project would not have been possible without his invaluable guidance and assistance. My deepest appreciation goes to my piano teacher, Professor Lita Guerra, whose unconditional support and encouragement gave me strength and faith to complete the treatise. Acknowledgment is gratefully made to the publisher for the use of the musical examples. Credit is given to Alexander Scriabin: Five Preludes, Op. 74 [public domain]. Piano score originally published by the Izdatel’stvo Muzyka [Music Publishing House], Moscow, 1967, reprinted 1973 by Dover Publications, Inc. Minneola, N.Y. v FIVE PRELUDES OPUS 74 BY ALEXANDER SCRIABIN: THE MYSTIC CHORD AS BASIS FOR NEW MEANS OF HARMONIC PROGRESSION Publication No._____________ Chia-Lun Chang, D.M.A. -

Analysis of JS Bach's Wohltemperirtes Clavier

ELL DE'- .- >LEASE HANDLE WITH CAIIE University of Connecticut Libraries 3 ^153 DinS=lE3 a GAYLORD RG AUGENER'S EDITION. No. 9205 ANALYSIS OF J, S. BACH'S Wohltemperirtes Clavier (48 Preludes & Fugues) BY Dr. H. RIEMANN TRANSLATED FROM THE GERMAN BY J. S. SHEDLOCK, B.A. PART I. PRELUDES & FUGUES Nos. 1 to 24 FIFTH IMPRESSION AUGENER Ltd. LONDON MUSIC LiBRAKs ONIVERSITY OF OjHHliM^KH, STORRS. CONNtCTIuUT TO Prof. Dr. PHILIPP SPITTA THE ENTHUSIASTIC BIOGRAPHER OP J, S. BACH Printed in England AUGENER Ltd., 287 Acton Lane, London, W. 4. CONTENTS. (MKST PAKT.) Page Preface to German Edition , . e * • . I Preface to English Edition . ... Ill Tranblation of the same into German Xll Analysis of all the Preludes and Fugues of «he Well-tempered Clavier in the chromatic succession of keys; — No. I in C-major . , l ,, 2 ,, C-minor . 8 » 3 n Cjj-major 15 ^ 4 „ CJf-minor 23 „ 5 „ D-major 32 „ 6 „ D-minor 39 7 „ E|7-major 45 „ 8 „ Ei7-minor 54 „ 9 „ E- major 60 „ 10 „ E-minor 63 „ II „ F-major . 69 „ 12 „ F-minor 76 „ 13 „ Fft-major 82 „ 14 „ F^-minor 87 „ 15 „ G-major 94 „ 16 ,, G-minor 99 -, 17 „ AF-major 106 „ 18 „ Gjt-minor Ill „ 19 ,1 A -major 120 „ 20 „ A-minor . 128 „ 21 „ b1?. major 133 „ 22 „ Bt^-miuor . 138 „ 23 „ B-major 147 „ 24 „ B-niinor 154 PREFACE. The present analysis of J. S. Bach's "Wohl- temperirtes Clavier" may be regarded as a sequel to the "Catechism of Composition", and specially as a Guide to fugal composition by the help of the most wonderful master-pieces in this branch of musical art; for to students of composition good examples are far more profitable than abstract rules and vague pre- scripts. -

Interpreting Chopin – the Preludes, Op.28 by Angela Lear

Interpreting Chopin – The Preludes, Op.28 by Angela Lear Chopin's modest choice of title, Preludes, for his remarkable set of twenty-four miniature masterpieces has often prompted the question, "Preludes to what?" Historically, preludes for the keyboard appeared as early as the 15th century in the organ tablatures from Germany. The 'prelude' evolved from a variety of compositions related to the period and nationality of the composer. These ranged from relatively basic compositions of a cadentially harmonic design or improvisatory nature and those intended to serve as a preparation to the audience for compositions that followed, to extended highly decorated preludes displaying the virtuosity of the performer. The 'independent' short keyboard Prelude had been written by Bach, his Little Preludes, and later in the early 19th-century there were many similarly composed collections, including; Chaulieu's 24 Little Preludes (early 1820's), Hummel's Vorspiele Op.67 (1818), and those of Czerny, Kalkbrenner, Cramer, Clementi, Szymanowska, Moscheles, etc.. Chopin would no doubt have been familiar with many of these compositions. It is also relevant to mention Klengel's 1829 performance of his own Canons and Fugues in all Major and Minor Keys which drew Chopin's attention at the time. It was not unusual for Chopin to take from existing forms those elements, fundamental characteristics and genre titles he required in order to create compositions of supreme originality. His innovative genius knew no bounds and as the master-craftsman he idealised each genre to make it entirely his own unique art form - and the Preludes are no exception. He had previously composed an 'independent' Prelude in Ab major (dating from 1834 and published posthumously in 1918: Kobylanska K.1231-2). -

PRELUDES Opus 28

PRELUDES, O p u s 2 8 First-edition imprints First-edition imprints of a work by Chopin are shown below. The Collection’s scores for the work are described on the pages that follow. To go directly to a description, click the score’s imprint in the Bookmarks panel on the left. PRELUDES Opus 28 Paris: Catelin (560) 1839 Composed 1838–39 Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel (6088) 1839 Brown 107 London: Wessel (3098) (3099) 1839 Chominski & Turlo 166 PRELUDES, O p u s 2 8 Paris: Catelin (560) [= 1839] 28-Ca-1 M22.C54 P93 ———— Livre 1 (preludes 1–12) 24 | PRÉLUDES | POUR | le Piano, | dédiés à son ami | CAMILLE PLEYEL, | PAR | FRÉD. CHOPIN | f [handwritten “1e.r ”] Livre. « » Prix 7 . 50. | Divisés en deux Livres | PARIS, chez AD. CATELIN et CI.E Editeurs des Compositeurs réunis, Rue Grange Bateliére, N o. 26. | Londres, chez Wessel et C o. « Ad. C. (560) et C I.E » Leipzig, chez Breitkopf et Haertel. | Gravé par A. Vialon. 10 leaves (340 x 255 mm): pp. [i] engr title page, [ii, 1] blank, 2–17 engr music, [18] blank. caption title: p. 2, ‘F. CHOPIN. « » 24 PRÉLUDES.’. sub-caption: p. 2, ‘I.’; and so on through p. 16, ‘XII.’. footline: pp. 2–16, ‘1e.r Liv: « Ad e. C. (560) & Ci.e ’; p. 17, ‘1e.r Liv: Ade. CATELIN & Ci.e « Ade. C. (560) & Ci.e » 26. Rue Grange Batèliere.’. Livre 2 (preludes 13–24) The title page is identical to that of Livre 1, except for the handwritten volume number. 14 leaves (340 x 255 mm): pp.