Fathom 2019/2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Love Stories: Narrative Ethics and the Novel from Stowe to James

American Love Stories: Narrative Ethics and the Novel from Stowe to James By Ashley Carson Barnes A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Dorothy Hale, Chair Professor Samuel Otter Professor Dorri Beam Professor Robert Alter Fall 2012 1 Abstract American Love Stories: Narrative Ethics and the Novel from Stowe to James by Ashley Carson Barnes Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Berkeley Professor Dorothy Hale, Chair “American Love Stories” argues for the continuity between two traditions often taken to be antagonistic: the sentimental novel of the mid-nineteenth century and the high modernism of Henry James. This continuity emerges in the love stories tracked here, from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Elizabeth Stuart Phelps’s The Gates Ajar, through Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Blithedale Romance and Herman Melville’s Pierre, to Elizabeth Stoddard’s The Morgesons and James’s The Golden Bowl. In these love stories—the other side of the gothic tradition described by Leslie Fiedler—desire is performed rather than repressed, and the self is less a private container than a public exhibit. This literary-historical claim works in tandem with the dissertation’s argument for revising narrative ethics. The recent ethical turn in literary criticism understands literature as practically engaging the emotions, especially varieties of love, that shape our social lives. It figures reading as a love story in its own right: an encounter with a text that might grant us intimacy with an authorial persona or else spurn our desire to grasp its alterity. -

Spring 1986 Editor: the Cover Is the Work of Lydia Sparrow

'sReview Spring 1986 Editor: The cover is the work of Lydia Sparrow. J. Walter Sterling Managing Editor: Maria Coughlin Poetry Editor: Richard Freis Editorial Board: Eva Brann S. Richard Freis, Alumni representative Joe Sachs Cary Stickney Curtis A. Wilson Unsolicited articles, stories, and poems are welcome, but should be accom panied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope in each instance. Reasoned comments are also welcome. The St. John's Review (formerly The Col lege) is published by the Office of the Dean. St. John's College, Annapolis, Maryland 21404. William Dyal, Presi dent, Thomas Slakey, Dean. Published thrice yearly, in the winter, spring, and summer. For those not on the distribu tion list, subscriptions: $12.00 yearly, $24.00 for two years, or $36.00 for three years, paya,ble in advance. Address all correspondence to The St. John's Review, St. John's College, Annapolis, Maryland 21404. Volume XXXVII, Number 2 and 3 Spring 1986 ©1987 St. John's College; All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited. ISSN 0277-4720 Composition: Best Impressions, Inc. Printing: The John D. Lucas Printing Company Contents PART I WRITINGS PUBLISHED IN MEMORY OF WILLIAM O'GRADY 1 The Return of Odysseus Mary Hannah Jones 11 God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob Joe Sachs 21 On Beginning to Read Dante Cary Stickney 29 Chasing the Goat From the Sky Michael Littleton 37 The Miraculous Moonlight: Flannery O'Connor's The Artificial Nigger Robert S. Bart 49 The Shattering of the Natural Order E. A. Goerner 57 Through Phantasia to Philosophy Eva Brann 65 A Toast to the Republic Curtis Wilson 67 The Human Condition Geoffrey Harris PART II 71 The Homeric Simile and the Beginning of Philosophy Kurt Riezler 81 The Origin of Philosophy Jon Lenkowski 93 A Hero and a Statesman Douglas Allanbrook Part I Writings Published in Memory of William O'Grady THE ST. -

A Critical Study of the Novels of John Fowles

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 1986 A CRITICAL STUDY OF THE NOVELS OF JOHN FOWLES KATHERINE M. TARBOX University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation TARBOX, KATHERINE M., "A CRITICAL STUDY OF THE NOVELS OF JOHN FOWLES" (1986). Doctoral Dissertations. 1486. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/1486 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CRITICAL STUDY OF THE NOVELS OF JOHN FOWLES BY KATHERINE M. TARBOX B.A., Bloomfield College, 1972 M.A., State University of New York at Binghamton, 1976 DISSERTATION Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English May, 1986 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. This dissertation has been examined and approved. .a JL. Dissertation director, Carl Dawson Professor of English Michael DePorte, Professor of English Patroclnio Schwelckart, Professor of English Paul Brockelman, Professor of Philosophy Mara Wltzllng, of Art History Dd Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. I ALL RIGHTS RESERVED c. 1986 Katherine M. Tarbox Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. to the memory of my brother, Byron Milliken and to JT, my magus IV Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

2016 Film Festival Programme

TAKE THE FORM OF COMMODITIES, VANISHES THEREFORE, SO SOON AS WE COME TO OTHER FORMS OF PRODUCTION THE FORM OF COMMODITIES, VANISHES TAKE SURROUNDS THE PRODUCTS OF LABOUR AS LONG THEY OF COMMODITIES, ALL THE MAGIC AND NECROMANCY THAT THE WHOLE MYSTERY k k belfast Belfast Film Festival film festival 14th-23rd April 2016 16 OUR FUNDERS ACCOMMODATION OFFICIAL MEDIA PARTNER PARTNERS OFFICIAL DRINKS SPONSOR VENUE PARTNERS INTRODUCTION The 16th Belfast Film Festival like any self-loathing teenager – has attitude! It is packed with premieres, guests, documentaries, shorts and much more. This year we present our biggest programme ever, with more than 133 films and events from 30 countries around the world. We welcome as our special guest, a man who is arguably the greatest living British filmmaker, Terence Davies. Belfast Film Festival is delighted to be honouring Terence with our Outstanding Contribution to Cinema award. Programme highlights include Stephen Frears’ hilarious new feature starring Hugh Grant with Meryl Streep as ‘Florence Foster Jenkins’; the Oscar-nominated must-see Turkish film ‘Mustang’; a 6 hour marathon watch with ‘Arabian Nights’, the mastery of Alan Clarke; the brilliant Icelandic tale ‘Virgin Mountain’, and the 2016 Oscar Winner Son of Saul. We have an exciting celebration of the artistry of sound in film in partnership with SARC; films on 1916; discussions; music; fancy dress; film installations, and a plethora of new talent in our short film and NI Independents sections; And perhaps most exciting of all we have a programme of new film showcasing more female directors than ever before. Michele Devlin. -

Read Greyrock Review

GREYROCK REVIEW 2021 Greyrock Review is Colorado State University’s journal of undergradu- ate art and literature. Published annually in the spring through the English Department, Greyrock Review is a student-run publication. Submissions: Th e journal accepts submissions for art, poetry, creative Managing Editor nonfi ction, and fi ction each year in the fall from undergraduate Emily Byrne students of all majors at Colorado State University. Poetry Editor Sarahy Quintana Trejo Special thanks to the Lilla B. Morgan Memorial Endowment for the Arts for providing a grant to make this year’s publication possible. Th e Associate Poetry Editor Melissa Downs Lilla B. Morgan Memorial Endowment for the Arts provides grants to support art, music, humanities, literature, and the performing arts. Fiction Editor Mira Martin Cover Art by Samantha Homan Associate Fiction Editors Katie Harrigan Cover Design by Katrina Clasen Brendon Shepherd Logo Design by Renee Haptonstall © 2021 Greyrock Review Creative Non ction Editor Cody Cooke All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, in Associate Non ction Editor any form or by any means, without prior written consent from Aubrie Dickson Greyrock Review. Typesetter & Designer Katrina Clasen Greyrock Review Department of English Social Media Manager Katie Harrigan Colorado State University 359 Eddy Hall Graduate Advisor Carolyn Janecek Fort Collins, CO 80523 English.colostate.edu/greyrock/ Faculty Advisor Stephanie G’Schwind Printed in the United States. Sponsors Lilla B. Morgan Memorial Endowment CSU English Department POETRY FICTION Audrey Heffelfinger 8 Papa Maia Coen 13 City Lights Brynn McCall 10 beast / body Sydney James 45 Real Girl Maia Coen 23 Spider’s Silk Kate Breding 68 Miss A Kayla Henn 33 tears aren’t a woman’s only weapon PJ Farrar 35 conjecture, surmise, theorize (or: just wondering why) 80 The Kindly One Ethan Hanson Abigail Wolschon 44 A Revolution Poem 103 Cave Hunters Charlie Dillon 58 to all the Selves that i have been: No. -

Selected Poems of Post-Beat Poets Also by Vernon Frazer

Selected Poems of Post-Beat Poets Also by Vernon Frazer POETRY Bodied Tone (Otoliths 2007) Holiday Idylling (BlazeVox 2006) IMPROVISATIONS (Beneath the Underground 2005) Avenue Noir (xPress(ed) 2004) Moon Wards (Poetic Inhalation 2003) Amplitudes (Melquiades/Booksout 2002) Demolition Fedora (Potes & Poets 2000) Free Fall (Potes & Poets 1999) Sing Me One Song of Evolution (Beneath the Underground 1998) Demon Dance (Nude Beach 1995) A Slick Set of Wheels (Water Row 1987) FICTION Commercial Fiction (Beneath the Underground 2002) Relic’s Reunions (Beneath the Underground 2000) Stay Tuned to This Channel (Beneath the Underground 1999) RECORDINGS Song of Baobab (VFCI 1997) Slam! (Woodcrest 1991) Sex Queen of the Berlin Turnpike (Woodcrest 1988) ANTHOLOGIES Selected Poems by Post-Beat Poets, Editor (Shanghai Century Publishing 2007) 2: An Anthology of New Collaborative Poetry (Sugar Mule 2007) The Poetry Readings by American and Chinese Poets (Hebei Education Press 2004) THOMAS CHAPIN–ALIVE (Knitting Factory Works 2000) THE JAZZ VOICE (Knitting Factory Works 1995) Selected Poems of Post-Beat Poets edited by Vernon Frazer Copyright © 2008 by Vernon Frazer Originally published in Chinese by Shanghai Century Publications Beijing, China CONTENTS Acknowledgments 11 Preface 13 Lawrence Carradini 15 After The Talking 16 Flexible Head 18 Just Above Freezing 19 Out 21 And Again 22 A Second Look 23 Terra Cotta Pater 24 Erin Fly'n 25 Steve Dalachinsky 26 Post - Beat - Poets (We Are Credo #2) 27 Empire 29 something ( for Cooper-Moore ) 30 rear window 1 31 -

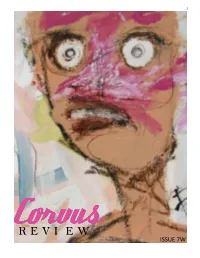

R E V I E W Issue 7W 2

1 R E V I E W ISSUE 7W 2 This issue of Corvus Review is dedicated to: Margaret “Marg” Josephine Pittman Feb 22, 1922-Feb. 13, 2017 EDITORS: Janine “Typing Tyrant” Mercer, EIC Luciana Fitzgerald, Fiction Editor COVER ART: C.F. Roberts Writer/Artist/Videographer/Provocateur/High -Functioning Autistic/Former Zine Publisher. Blog: http://cfrobertsuselessfilth.blogspot.com/ Art: http://cfrobertsuselessfilth.blogspot.com/ 3 4. R.Q. Flanagan 5. N. Sumislaski 6. T.L. Naught 8. A. Tipa 9. J. Riccio 11. D. Fagan 12. S.A. Ortiz 13. A. Cole 14. R.G. Foster 15. L. Suchenski 16. D. Tuvell 17. M. L. Johnson 18. S. Laudati 19. R. Nisbet 20. R. Hartwell N.F. 57. M.D. Laing 92. C. Valentza 23. M. Watson N.F. 62. S. Roberts 93. D.D. Vitucci 27. T. Smith N.F. 63. J. Hunter 96. J. Hickey 28. G. Vachon N.F. 67. N. Kovacs 99. J. Bradley 31. K. Shields 69. T. Rutkowski 100. S.F. Greenstein 32. J. Half-Pillow 70. B. Diamond 104. J. Mulhern 37. M. Wren 72. F. Miller 109. B.A. Varghese 38. D. Clark 79. K. Casey 113. K. Maruyama 39. P. Kauffmann 80. K. Hanson 119. K. Azhar 42. Z. Smith 82. J. Butler 120. Author Bio’s 44. J. Hill 83. R. Massoud 46. J. Gorman 86. M. Lee 51. B. Taylor 88. J. Rank 56. M.A. Ferro 4 On Taking a Complete Stranger to the Gynecologist Ryan Quinn Flanagan I have allergies and I have glow sticks and I have driven a complete stranger to the gynecologist, wondering about the sanitary nature of my passenger seat the whole time, playing it cool like Clint Eastwood with a cannon in my pants but soon feeling bad for the girl abandoned by family -

MCNAIR.Thesis.July 16.FINAL

THE HISTORY OF KAKAWANGWA by Kristen McNair A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida August 2012 THE mSTORY OF KAKAWANGW A by Kristen. MeN air This thesis was prepared under the direction of the candidate's thesis advisor, Professor Andrew Furman, Department of English, and has been approved by the members of her supervisory committee. It was submitted to the faculty of the Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters and was accepted in partial fulfillment for the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts. AndrewThriAdVisor Furman, Ph.D. Ayse 'r:t{tBU~ Johnnie Stover, Ph.D~ Heather Coltman, D .M.A. Interim Dean, The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts & Letters B!r7;ss":pr!---. Dean, Graduate College 11 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the professors who worked with me on this project: Dr. Andrew Furman, Ayse Papatya Bucak, and Dr. Johnnie Stover. Your feedback regarding my writing and my novel has been invaluable. Thank you for the encouragement and for requiring my very best. To mom, Tory, my siblings, and extended family and friends, you encouraged me to embrace my identity as a storyteller. Thanks to Robert Olen Butler, Melvin Sterne, Paul Shepherd, and Elizabeth Stuckey- French for teaching me how to write fiction in the first place. Thanks to my loving husband and daughter, for allowing me to ignore the world and write this novel. -

The Bear Went Over the Mountain

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-21-2004 The Bear Went Over the Mountain Sonja Mongar University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Mongar, Sonja, "The Bear Went Over the Mountain" (2004). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 76. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/76 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE BEAR WENT OVER THE MOUNTAIN A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing by Sonja S. Mongar B.A. University of North Florida, 1994 M.A. University of Central Florida, 2001 May 2004 Copyright 2004, Sonja S. Mongar ii DEDICATION For those who come after us: Dakota, Connor, Eric Jr., Ross, Tylor, Joey, Clarence and Hillary iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Melvin, mi media naranja, has been with me during this entire project, from listening to every painful revelation to spending hours, even days figuring out how to layout text and meet format requirements. -

Fore Majeure and Other Stories

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Theses UMSL Graduate Works 4-19-2010 Fore Majeure and Other Stories Jennifer Megan Nord University of Missouri-St. Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://irl.umsl.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Nord, Jennifer Megan, "Fore Majeure and Other Stories" (2010). Theses. 94. https://irl.umsl.edu/thesis/94 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the UMSL Graduate Works at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Force Majeure and Other Stories by JENNIFER MEGAN NORD B.A., English, University of Missouri – St. Louis, 2002 B.A. Psychology, University of Missouri – St. Louis, 2002 A THESIS Submitted to the Graduate School of the UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI- ST. LOUIS In partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF FINE ARTS in CREATIVE WRITING with an emphasis in Fiction May, 2010 Advisory Committee John Dalton, M.F.A. Chairperson Mary Troy, M.F.A. Steve Schreiner, Ph.D., M.F.A. Abstract Force Majeure and Other Stories explores the imperfect way people often make life- altering decisions. Many times, this results from circumstance — an unexpected situation requiring an immediate decision presents itself — but we also often bring the need for such decisions upon ourselves, when our dissatisfaction with the banality of everyday life leads to the desire to pursue an imagined, and many times idealized, alternate reality. This collection of short stories explores the factors that shape our decisions — from inertia to the strength of emotional ties. -

Thesis (943.4Kb)

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2017 Penetralia Nelson, Brandon Nelson, B. (2017). Penetralia (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/27282 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/3576 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Penetralia by Brandon Nelson A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN ENGLISH CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY, 2017 © Brandon Nelson 2017 Abstract Penetralia is a short fiction collection that occupies the fissures between the minds and bodies of its protagonists. Each story involves an uncanny disruption of identity that results in personal, social, and sexual convulsion and collapse. The convulsions are many: a man finds wisdom in silence when he is numbed and unable to speak during a tooth extraction, a woman uses cuddle parties to escape her anxiety and obsessive rituals, Marlene Dietrich converses casually with a marketer licensing her image posthumously, a confused revolution strikes its first blow after a fertility clinic refuses to inseminate across racial lines, a renowned writer plagiarizes from a schizophrenic homeless man, and a stand-up comedienne listens for echoes of herself from the other side of the spotlight. -

00:00:05 Stuart Host and the Lesson Is, Watch This Movieee! [Laughs.] 00:00:08 Music Music Light, Up-Tempo, Electric Guitar with Synth Instruments

00:00:00 Dan Host On this episode we discuss—Deadly Lessons! 00:00:05 Stuart Host And the lesson is, watch this movieee! [Laughs.] 00:00:08 Music Music Light, up-tempo, electric guitar with synth instruments. 00:00:35 Dan Host Hey, everyone, and welcome to The Flop House. I’m Dan McCoy. 00:00:38 Stuart Host Oh hey there, Dan McCoy, it’s me—Stuart Wellington! Your friend! 00:00:41 Elliott Host I’m Elliott Kalan! I also fall into the category of “friend.” Not just to Dan, but also to Stuart! Three friends are we. Yes, friends are us. [Dan laughs.] 00:00:50 Stuart Host And that’s what this is. This is a podcast where three friends are friends and they talk about friend stuff. 00:00:54 Crosstalk Crosstalk Elliott and Dan: Mm-hm. [Laughs.] Dan: So, friends— Stuart: In particular— 00:00:58 Stuart Host The way that friends sometimes watch movies and then talk about it. What did we do this week, Dan, on the Friendcast? 00:01:03 Elliott Host Welcome to the Friend House! 00:01:05 Dan Host Well, we—during September, at the Friend House, we celebrate Smalltember. 00:01:11 Elliott Host Smallvember. 00:01:12 Crosstalk Crosstalk Dan: Which is a made-up holiday month where we watch— [Laughs.] Okay. Good point. Stuart: All holidays are made up. [Elliott laughs.] Elliott: Uh, there’s a lot of religious people who will be very unhappy with you saying that, Stuart. 00:01:23 Stuart Host Oh, burn! They can come find me at Dan’s apartment! [Dan laughs.] 00:01:27 Crosstalk Crosstalk Elliott: I mean, you do have a— Dan: Wait— 00:01:28 Elliott Host Stuart, you have a public business that people can go to, to talk to you face-to-face.