Interaction of the Gospel and Culture in Bengal T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alexander Duff Pioneer of Missionary Education Alexand Er Duff a T Th I Rty Alexander Duff Pioneer of Missionary Education

ALEXANDER DUFF PIONEER OF MISSIONARY EDUCATION ALEXAND ER DUFF A T TH I RTY ALEXANDER DUFF PIONEER OF MISSIONARY EDUCATION By WILLIAM PATON ACTING SECRETARY OF THB INDIA NATIONAL MISSIONARY COUNCIL LATE MISSIONARY SECRETARY OF THE STUDENT CHRISTIAN MOVEMENT JOINT• AUTHOR OF "THE HIGHWAY OF GOD" AND AUTHOR OF "SOCIAL IDEALS IN INDIA, 11 ETC. WNDON STUDENT CHRISTIAN MOVEMENT 32 RUSSELL SQUARE, W.C.l 1923 Made atul Printed in Great Britain by Turnbwll 6' Spears, Edinburrlt EDITORIAL NOTE THIS volume is the second of a uniform series of new missionary biographies. The series makes no pretence of adding new facts to those already known. The aim rather is to give to the world of to-day a fresh interpretation and a richer understanding of the life and work of great missionaries. A group of unusually able writers are collaborating, and three volumes will be issued each year. The enterprise is being undertaken by the United Council for Missionary Education, for whom the series is published by the Student Christian Move ment. K. M. U.C.M.E. A. E. C. 2 EATON GATE S.W.l 6 TO DAVID AND JAMES AUTHOR'S PREFACE SoME apology is needed for the appearance of a new sketch of the life of Alexander Duff, especially as the present writer cannot lay claim to any special sources of information which were not available when the earlier biographies were written. The reader will not find in this book fresh light on Duff, except in so far as the course of events in itself proves a man's work and makes clear its strength and weakness. -

Aspects of Indian Modernity: a Personal Perspective

ASPECTS OF INDIAN MODERNITY: A PERSONAL PERSPECTIVE MOHAN RAMANAN University of Hyderabad, India [email protected] 75 I There are two Indias. One is called Bharat, after a legendary King. This represents a traditional culture strongly rooted in religion. The other is India, the creation of a modern set of circumstances. It has to do with British rule and the modernities set in motion by that phenomenon. India as a nation is very much a creation of the encounter between an ancient people and a western discourse. The British unified the geographical space we call India in a manner never done before. Only Asoka the Great and Akbar the Great had brought large parts of the Indian sub- continent under their control, but their empires were not as potent or as organized as the British Empire. The British gave India communications, railways, the telegraph and telephones; they organized their knowledge of India systematically by surveying the landscape, categorizing the flora and fauna and by dividing the population into castes and religious groupings. Edward Said has shown in his well- known general studies of the colonial enterprise how this accumulation of knowledge is a way of establishing power. In India the British engaged themselves in this knowledge accumulation to give themselves an Empire and a free market and a site to work their experiments in social engineering. This command of the land also translated into command of the languages of the people. British scholars like G.U. Pope and C.P. Brown, to name only two, miscelánea: a journal of english and american studies 34 (2006): pp. -

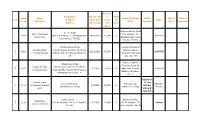

Comp. Sl. No Name S/D/W/O Designation & Office Address Date of First Application (Receving) Basic Pay / Pay in Pay Band Type

Basic Pay Designation Date of First / Type Comp. Name Name & Address Roster Date of Date of Sl. No. & Office Application Pay in of Status Sl. No S/D/W/O D.D.O. Category Birth Retirement Address (Receving) Pay Flat Band Accounts Officer, 9D & Gr. - II Sister Smt. Anita Biswas B.G. Hospital , 57, 1 1879 9D & B.G. Hospital , 57, Beleghata Main 28/12/2012 21,140 A ALLOTTED Sri Salil Dey Beleghata Main Road, Road, Kolkata - 700 010 Kolkata - 700 010 District Fishery Officer Assistant Director of Bikash Mandal O/O the Deputy Director of Fisheries, Fisheries, Kolkata 2 1891 31/12/2012 22,500 A ALLOTTED Lt. Joydev Mandal Kolkata Zone, 9A, Esplanade East, Kol - Zone, 9A, Esplanade 69 East , Kol - 69 Asstt. Director of Fishery Extn. Officer Fisheries, South 24 Swapan Kr. Saha O/O The Asstt. Director of Fisheries 3 1907 1/1/2013 17,020 A Pgns. New Treasury ALLOTTED Lt. Basanta Saha South 24 Pgs., Alipore, New Treasury Building (6th Floor), Building (6th Floor), Kol - 27 Kol - 27 Eligible for Samapti Garai 'A' Type Assistant Professor Principal, Lady Allotted '' 4 1915 Sri Narayan Chandra 2/1/2013 20,970 A flats but Lady Brabourne College Brabourne College B'' Type Garai willing 'B' Type Flat Staff Nurse Gr. - II Accounts Officer, Lipika Saha 5 1930 S.S.K.M. Hospital , 244, A.J.C. Bose Rd. , 4/1/2013 16,380 A S.S.K.M. Hospital , 244, Allotted Sanjit Kumar Saha Kol -20 A.J.C. Bose Rd. , Kol -20 Basic Pay Designation Date of First / Type Comp. -

Rosinka Chaudhuri Name

Curriculum Vitae : Rosinka Chaudhuri Name: Rosinka Chaudhuri Institutional Affiliation: Director and Professor of Cultural Studies, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta. Last Educational Qualification: Name of University Dates Degree Class University of Oxford 1990-96 D. Phil. Ph.D. Research and Teaching Experience Research - Inaugural Mellon Professor of the Global South at the University of Oxford, 2017-18. - Visiting Senior Research Fellow at the India Institute, King’s College, London, 8 May – 8 June 2016. - Visiting Fellow, Delhi University, 31 March – 4 April 2014. - Charles Wallace Fellow, Centre of South Asian Studies, University of Cambridge, 2005. - Visiting Fellow at the Centre of South Asian Studies, Columbia University, 2002. - Junior Research Fellowship from the University Grants Commission, University of Poona, 1989. - Research fellowship from the American Studies Research Centre, Hyderabad, 1990. 2 Teaching - Co-ordinating and teaching M. Phil. Course at the CSSSC called ‘Introduction to Modern Social Thought’. - Co-teaching two M. Phil. Courses at the CSSSC called ‘Readings in Philosophy: Things, Commodities, Consumptions’, and ‘Research Methods’. Publications Books 1. The Literary Thing: History, Poetry and the Making of a Modern Cultural Sphere (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2013; Oxford: Peter Lang, 2014). 2. Freedom and Beef Steaks: Colonial Calcutta Culture (Delhi: Orient Blackswan, 2012). 3. Gentlemen Poets in Colonial Bengal: Emergent Nationalism and the Orientalist Project, (Calcutta: Seagull Books, 2002). Edited Books 1. An Acre of Green Grass: English Writings of Buddhadeva Bose (forthcoming in June 2018 from Oxford University Press, New Delhi). 2. A History of Indian Poetry in English (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016). 3. The Indian Postcolonial: A Critical Reader, co-edited with Elleke Boehmer, (London: Routledge, 2010). -

'Grand and Capacious Gothic Churches': Pluralism and Victorian

Tyndale Bulletin 43.1 (1992) 139-154. ‘GRAND AND CAPACIOUS GOTHIC CHURCHES’: PLURALISM AND VICTORIAN MISSIONARIES Peter Williams Nothing is easier than to set the nineteenth century missionary movement up as a resource for negative models of missionary work. Thus its missionaries can easily be presented as unreflective imperialists—the bible in one hand, with the flag of their country in the other; as culturally insensitive imagining that no objective was higher than replicating European and American value systems in previously pagan settings; as narrowly evangelistic without any concern for a fully-orbed Gospel able to take account of social needs; as uncomprehendingly hostile to every religious system they met which was not Christian, indeed which was not evangelical Christian. There is obviously some truth in all of these assessments and it would not be difficult to assemble apparently supportive evidence. It will be argued however that there was a much stronger awareness of the issues than we often credit; that theologically the insights were often quite profound; that weaknesses there undoubtedly were but that these related less to an absence of theology than to a disputed theology. In brief Victorian missionaries provide not an example of a generation which thought little or which thought simplistically about mission strategy but rather one where the thinking, at any rate of some of its some most significant figures, was unexpectedly profound. If that is so, then it makes them somewhat more disturbing. It is not then that they lacked sophistication but rather that they very imperfectly implemented a quite profound analysis. They did not for example fail to move from mission to Church because they ignored the question—indeed they provided quite detailed analysis of how that end could be achieved. -

Landscaping India: from Colony to Postcolony

Syracuse University SURFACE English - Dissertations College of Arts and Sciences 8-2013 Landscaping India: From Colony to Postcolony Sandeep Banerjee Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/eng_etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, Geography Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Banerjee, Sandeep, "Landscaping India: From Colony to Postcolony" (2013). English - Dissertations. 65. https://surface.syr.edu/eng_etd/65 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in English - Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT Landscaping India investigates the use of landscapes in colonial and anti-colonial representations of India from the mid-nineteenth to the early-twentieth centuries. It examines literary and cultural texts in addition to, and along with, “non-literary” documents such as departmental and census reports published by the British Indian government, popular geography texts and text-books, travel guides, private journals, and newspaper reportage to develop a wider interpretative context for literary and cultural analysis of colonialism in South Asia. Drawing of materialist theorizations of “landscape” developed in the disciplines of geography, literary and cultural studies, and art history, Landscaping India examines the colonial landscape as a product of colonial hegemony, as well as a process of constructing, maintaining and challenging it. In so doing, it illuminates the conditions of possibility for, and the historico-geographical processes that structure, the production of the Indian nation. -

Written'', in the Shahbazgarhi Text of A£Olca's Rock-Edicts (Above, 1913, P

VARENDRA 97 I avail myself of this opportunity for a correction of my remarks on the participle nipista, " written'', in the Shahbazgarhi text of A£olca's rock-edicts (above, 1913, p. 654). It must not be derived from the Sanskrit nish- pishta, " ground ", but rather from nipishta, " written ", whicli occurs repeatedly in the inscriptions of the Achse- menidan kings of Persia; see Professor Tolman's Ancient Persian Lexicon, New York, 1908, p. 111. The word is still living in the modern Persian {J^>y, " to write". As the Shahbazgarhi version is the only one in which the Indian likhita, " written ", is replaced by nipista, would it be too hazardous to assume that the latter is a foreign word which was imported from Iran along with the KharoshthI alphabet ? And may pustaka, " a book ",— a word for which no satisfactory etymology is found in Sanskrit—be connected with it ? E. HULTZSCH. VARENDRA The Varendra Anusandhana Samiti (Research Society) was started in the year 1910, in the district of Rajshahi in Northern Bengal, chiefly through the exertions of Kumar Sarat Kumar Roy, M.A., of Dighapatiya in that district, with the object of carrying on antiquarian research in the tract of country called in Sanskrit literature Varendra, and in modern colloquial language " the Barind ". This is a tract of comparatively high land, which includes portions of the Malda, Rajshahi, Dinajpur, Rangpur, and Bogra Districts in the Rajshahi Division, with a stiff soil of reddish clayey loam, distinguishing it from the remainder of those districts, the soil of which is sandy alluvium of recent formation. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Conversion in the Pluralistic Religious Context of India: a Missiological Study

Conversion in the pluralistic religious context of India: a Missiological study Rev Joel Thattupurakal Mathai BTh, BD, MTh 0000-0001-6197-8748 Thesis submitted for the degree Philosophiae Doctor in Missiology at the Potchefstroom Campus of the North-West University in co-operation with Greenwich School of Theology Promoter: Dr TG Curtis Co-Promoter: Dr JJF Kruger April 2017 Abstract Conversion to Christianity has become a very controversial issue in the current religious and political debate in India. This is due to the foreign image of the church and to its past colonial nexus. In addition, the evangelistic effort of different church traditions based on particular view of conversion, which is the product of its different historical periods shaped by peculiar constellation of events and creeds and therefore not absolute- has become a stumbling block to the church‘s mission as one view of conversion is argued against the another view of conversion in an attempt to show what constitutes real conversion. This results in competitions, cultural obliteration and kaum (closed) mentality of the church. Therefore, the purpose of the dissertation is to show a common biblical understanding of conversion which could serve as a basis for the discourse on the nature of the Indian church and its place in society, as well as the renewal of church life in contemporary India by taking into consideration the missiological challenges (religious pluralism, contextualization, syncretism and cultural challenges) that the church in India is facing in the context of conversion. The dissertation arrives at a theological understanding of conversion in the Indian context and its discussion includes: the multiple religious belonging of Hindu Christians; the dual identity of Hindu Christians; the meaning of baptism and the issue of church membership in Indian context. -

Name of DDO/Hoo ADDRESS-1 ADDRESS CITY PIN SECTION REF

Name of DDO/HoO ADDRESS-1 ADDRESS CITY PIN SECTION REF. NO. BARCODE DATE THE SUPDT OF POLICE (ADMIN),SPL INTELLIGENCE COUNTER INSURGENCY FORCE ,W B,307,GARIA GROUP MAIN ROAD KOLKATA 700084 FUND IX/OUT/33 ew484941046in 12-11-2020 1 BENGAL GIRL'S BN- NCC 149 BLCK G NEW ALIPUR KOLKATA 0 0 KOLKATA 700053 FD XIV/D-325 ew460012316in 04-12-2020 2N BENAL. GIRLS BN. NCC 149, BLOCKG NEW ALIPORE KOL-53 0 NEW ALIPUR 700053 FD XIV/D-267 ew003044527in 27-11-2020 4 BENGAL TECH AIR SAQ NCC JADAVPUR LIMIVERSITY CAMPUS KOLKATA 0 0 KOLKATA 700032 FD XIV/D-313 ew460011823in 04-12-2020 4 BENGAL TECH.,AIR SQN.NCC JADAVPUR UNIVERSITY CAMPUS, KOLKATA 700036 FUND-VII/2019-20/OUT/468 EW460018693IN 26-11-2020 6 BENGAL BATTALION NCC DUTTAPARA ROAD 0 0 N.24 PGS 743235 FD XIV/D-249 ew020929090in 27-11-2020 A.C.J.M. KALYANI NADIA 0 NADIA 741235 FD XII/D-204 EW020931725IN 17-12-2020 A.O & D.D.O, DIR.OF MINES & MINERAL 4, CAMAC STREET,2ND FL., KOLKATA 700016 FUND-XIV/JAL/19-20/OUT/30 ew484927906in 14-10-2020 A.O & D.D.O, O/O THE DIST.CONTROLLER (F&S) KARNAJORA, RAIGANJ U/DINAJPUR 733130 FUDN-VII/19-20/OUT/649 EW020926425IN 23-12-2020 A.O & DDU. DIR.OF MINES & MINERALS, 4 CAMAC STREET,2ND FL., KOLKATA 700016 FUND-IV/2019-20/OUT/107 EW484937157IN 02-11-2020 STATISTICS, JT.ADMN.BULDS.,BLOCK-HC-7,SECTOR- A.O & E.O DY.SECY.,DEPTT.OF PLANNING & III, KOLKATA 700106 FUND-VII/2019-20/OUT/470 EW460018716IN 26-11-2020 A.O & EX-OFFICIO DY.SECY., P.W DEPTT. -

Setting the Stage: a Materialist Semiotic Analysis Of

SETTING THE STAGE: A MATERIALIST SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF CONTEMPORARY BENGALI GROUP THEATRE FROM KOLKATA, INDIA by ARNAB BANERJI (Under the Direction of Farley Richmond) ABSTRACT This dissertation studies select performance examples from various group theatre companies in Kolkata, India during a fieldwork conducted in Kolkata between August 2012 and July 2013 using the materialist semiotic performance analysis. Research into Bengali group theatre has overlooked the effect of the conditions of production and reception on meaning making in theatre. Extant research focuses on the history of the group theatre, individuals, groups, and the socially conscious and political nature of this theatre. The unique nature of this theatre culture (or any other theatre culture) can only be understood fully if the conditions within which such theatre is produced and received studied along with the performance event itself. This dissertation is an attempt to fill this lacuna in Bengali group theatre scholarship. Materialist semiotic performance analysis serves as the theoretical framework for this study. The materialist semiotic performance analysis is a theoretical tool that examines the theatre event by locating it within definite material conditions of production and reception like organization, funding, training, availability of spaces and the public discourse on theatre. The data presented in this dissertation was gathered in Kolkata using: auto-ethnography, participant observation, sample survey, and archival research. The conditions of production and reception are each examined and presented in isolation followed by case studies. The case studies bring the elements studied in the preceding section together to demonstrate how they function together in a performance event. The studies represent the vast array of theatre in Kolkata and allow the findings from the second part of the dissertation to be tested across a variety of conditions of production and reception. -

The Black Hole of Empire

Th e Black Hole of Empire Th e Black Hole of Empire History of a Global Practice of Power Partha Chatterjee Princeton University Press Princeton and Oxford Copyright © 2012 by Princeton University Press Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW press.princeton.edu All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chatterjee, Partha, 1947- Th e black hole of empire : history of a global practice of power / Partha Chatterjee. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-691-15200-4 (hardcover : alk. paper)— ISBN 978-0-691-15201-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Bengal (India)—Colonization—History—18th century. 2. Black Hole Incident, Calcutta, India, 1756. 3. East India Company—History—18th century. 4. Imperialism—History. 5. Europe—Colonies—History. I. Title. DS465.C53 2011 954'.14029—dc23 2011028355 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available Th is book has been composed in Adobe Caslon Pro Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To the amazing surgeons and physicians who have kept me alive and working This page intentionally left blank Contents List of Illustrations ix Preface xi Chapter One Outrage in Calcutta 1 Th e Travels of a Monument—Old Fort William—A New Nawab—Th e Fall