Iucn Technical Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Walk on the Wild Side

SCAPES Island Trail your chauffeur; when asked to overtake, he regards you with bewildered incomprehension: “Overtake?” Balinese shiftlessness and cerebral inertia exasperate, particularly the anguished Japanese management with their brisk exactitude at newly-launched Hoshinoya. All that invigorates Bali is the ‘Chinese circus’. Certain resort lobbies, Ricky Utomo of the Bvlgari Resort chuckles, “are like a midnight sale” pulsating with Chinese tourists in voluble haberdashery, high-heeled, almost reeling into lotus ponds they hazard selfies on. The Bvlgari, whose imperious walls and august prices discourage the Chinese, say they had to terminate afternoon tea packages (another Balinese phenomenon) — can’t have Chinese tourists assail their precipiced parapets for selfies. The Chinese wed in Bali. Indians honeymoon there. That said, the isle inspires little romance. In the Viceroy’s gazebo, overlooking Ubud’s verdure, a honeymooning Indian girl, exuding from her décolleté, contuses her anatomy à la Bollywood starlet, but her husband keeps romancing his iPhone while a Chinese man bandies a soft toy to entertain his wife who shuts tight her eyes in disdain as Mum watches on in wonderment. When untoward circumstances remove us to remote and neglected West Bali National Park, where alone on the island you spot deer, two varieties, extraordinarily drinking salt water, we stumble upon Bali’s most enthralling hideaway and meet Bali’s savviest man, general manager Gusti at Plataran Menjangan (an eco-luxury resort in a destination unbothered about -

From the Jungles of Sumatra and the Beaches of Bali to the Surf Breaks of Lombok, Sumba and Sumbawa, Discover the Best of Indonesia

INDONESIAThe Insiders' Guide From the jungles of Sumatra and the beaches of Bali to the surf breaks of Lombok, Sumba and Sumbawa, discover the best of Indonesia. Welcome! Whether you’re searching for secluded surf breaks, mountainous terrain and rainforest hikes, or looking for a cultural surprise, you’ve come to the right place. Indonesia has more than 18,000 islands to discover, more than 250 religions (only six of which are recognised), thousands of adventure activities, as well as fantastic food. Skip the luxury, packaged tours and make your own way around Indonesia with our Insider’s tips. & Overview Contents MALAYSIA KALIMANTAN SULAWESI Kalimantan Sumatra & SUMATRA WEST PAPUA Jakarta Komodo JAVA Bali Lombok Flores EAST TIMOR West Papua West Contents Overview 2 West Papua 23 10 Unique Experiences A Nomad's Story 27 in Indonesia 3 Central Indonesia Where to Stay 5 Java and Central Indonesia 31 Getting Around 7 Java 32 & Java Indonesian Food 9 Bali 34 Cultural Etiquette 1 1 Nusa & Gili Islands 36 Sustainable Travel 13 Lombok 38 Safety and Scams 15 Sulawesi 40 Visa and Vaccinations 17 Flores and Komodo 42 Insurance Tips Sumatra and Kalimantan 18 Essential Insurance Tips 44 Sumatra 19 Our Contributors & Other Guides 47 Kalimantan 21 Need an Insurance Quote? 48 Cover image: Stocksy/Marko Milovanović Stocksy/Marko image: Cover 2 Take a jungle trek in 10 Unique Experiences Gunung Leuser National in Indonesia Park, Sumatra Go to page 20 iStock/rosieyoung27 iStock/South_agency & Overview Contents Kalimantan Sumatra & Hike to the top of Mt. -

Mapping a Policy-Making Process the Case of Komodo National Park, Indonesia

THESIS REPORT Mapping a Policy-making Process The case of Komodo National Park, Indonesia Novalga Aniswara MSc Tourism, Society & Environment Wageningen University and Research A Master’s thesis Mapping a policy-making process: the case of Komodo National Park, Indonesia Novalga Aniswara 941117015020 Thesis Code: GEO-80436 Supervisor: prof.dr. Edward H. Huijbens Examiner: dr. ir. Martijn Duineveld Wageningen University and Research Department of Environmental Science Cultural Geography Chair Group Master of Science in Tourism, Society and Environment i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Tourism has been an inseparable aspect of my life, starting with having a passion for travelling until I decided to take a big step to study about it back when I was in vocational high school. I would say, learning tourism was one of the best decisions I have ever made in my life considering opportunities and experiences which I encountered on the process. I could recall that four years ago, I was saying to myself that finishing bachelor would be my last academic-related goal in my life. However, today, I know that I was wrong. With the fact that the world and the industry are progressing and I raise my self-awareness that I know nothing, here I am today taking my words back and as I am heading towards the final chapter from one of the most exciting journeys in my life – pursuing a master degree in Wageningen, the Netherlands. Never say never. In completing this thesis, I received countless assistances and helps from people that I would like to mention. Firstly, I would not be at this point in my life without the blessing and prayers from my parents, grandma, and family. -

Hemi Kingi by Brian Sheppard 9 Workshop Reflections by Brian Sheppard 11

WORLD HERITAGE MANAGERS WORKSHOP PROCEEDINGS OF THE WORLD HERITAGE MANAGERS WORKSHOP Tongariro National Park, New Zealand 26–30 October 2000 Contents/Introduction 1 WORLD HERITAGE MANAGERS WORKSHOP Cover: Ngatoroirangi, a tohunga and navigator of the Arawa canoe, depicted rising from the crater to tower over the three sacred mountains of Tongariro National Park—Tongariro (foreground), Ngauruhoe, and Ruapehu (background). Photo montage: Department of Conservation, Turangi This report was prepared for publication by DOC Science Publishing, Science & Research Unit, Science Technology and Information Services, Department of Conservation, Wellington; design and layout by Ian Mackenzie. © Copyright October 2001, New Zealand Department of Conservation ISBN 0–478–22125–8 Published by: DOC Science Publishing, Science & Research Unit Science and Technical Centre Department of Conservation PO Box 10-420 Wellington, New Zealand Email: [email protected] Search our catalogue at http://www.doc.govt.nz 2 World Heritage Managers Workshop—Tongariro, 26–30 October 2000 WORLD HERITAGE MANAGERS WORKSHOP CONTENTS He Kupu Whakataki—Foreword by Tumu Te Heuheu 7 Hemi Kingi by Brian Sheppard 9 Workshop reflections by Brian Sheppard 11 EVALUATING WORLD HERITAGE MANAGEMENT 13 KEYNOTE SPEAKERS Performance management and evaluation 15 Terry Bailey, Projects Manager, Kakadu National Park, NT, Australia Managing our World Heritage 25 Hugh Logan, Director General, Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand Tracking the fate of New Zealand’s natural -

Unraveling the Complexity of Human–Tiger Conflicts in the Leuser

Animal Conservation. Print ISSN 1367-9430 Unraveling the complexity of human–tiger conflicts in the Leuser Ecosystem, Sumatra M. I. Lubis1,2 , W. Pusparini1,4, S. A. Prabowo3, W. Marthy1, Tarmizi1, N. Andayani1 & M. Linkie1 1 Wildlife Conservation Society, Indonesia Program, Bogor, Indonesia 2 Asian School of the Environment,Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, Singapore 3 Natural Resource Conservation Agencies (BKSDA), Banda Aceh, Aceh Province, Indonesia 4 Wildlife Conservation Research Unit and Interdisciplinary Center for Conservation Science (ICCS), Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK Keywords Abstract human–tiger conflict; large carnivore; livestock; Panthera; poaching; research- Conserving large carnivores that live in close proximity to people depends on a implementation gap; retaliatory killing. variety of socio-economic, political and biological factors. These include local tol- erance toward potentially dangerous animals, efficacy of human–carnivore conflict Correspondence mitigation schemes, and identifying and then addressing the underlying causes of Muhammad I. Lubis, Asian School of the conflict. The Leuser Ecosystem is the largest contiguous forest habitat for the criti- Environment, Nanyang Technological cally endangered Sumatran tiger. Its extensive forest edge is abutted by farming University, Singapore. communities and we predict that spatial variation in human–tiger conflict (HTC) Email: [email protected] would be a function of habitat conversion, livestock abundance, and poaching of tiger and its wild prey. To investigate which of these potential drivers of conflict, Editor: Julie Young as well as other biophysical factors, best explain the observed patterns, we used Associate Editor: Zhongqiu Li resource selection function (RSF) technique to develop a predictive spatially expli- cit model of HTC. -

Singapore U Bali U Borneo Java U Borobudur U Komodo

distinguished travel for more than 35 years u u Singapore Bali Borneo Java u Borobudur u Komodo INDONESIA THAILAND a voyage aboard the Bangkok CAMBODIA Kumai BORNEO Exclusively Chartered Siem Reap South Angkor Wat China Sea Five-Star Small Ship Tanjung Puting National Park Java Sea INDONESIA Le Lapérouse SINGAPORE Indian Semarang Ocean BALI MOYO JAVA ISLAND KOMODO Borobudur Badas Temple Prambanan Temple UNESCO World Heritage Site Denpasar Cruise Itinerary BALI Komodo SUMBAWA Air Routing National Park Land Routing September 23 to October 8, 2021 Singapore u Bali u Sumbawa u Semarang Kumai u Moyo Island u Komodo Island xperience the spectacular landscapes, tropical E 1 Depart the U.S. or Canada biodiversity and vast cultural treasures of Indonesia and 2 Cross the International Date Line Singapore on this comprehensive, 16-day journey 3 Arrive in Singapore featuring four nights in Five-Star hotels and an eight-night 4-5 Singapore/Fly to Bali, Indonesia 6 Denpasar, Bali cruise round trip Bali aboard the exclusively chartered, 7 Ubud/Benoa/Embark Le Lapérouse Five-Star Le Lapérouse. Discover Singapore’s compelling 8 Cruising the Java Sea to Java ethnic tableau, Bali’s authentic cultural traditions and 9 Semarang, Java (Borobudur and Prambanan Temples) 10 Cruising the Java Sea to Borneo breathtaking scenery, and the UNESCO-inscribed 11 Kumai, Borneo/Tanjung Puting National Park temples of Borobudur and Prambanan. Embark on a 12 Cruising the Java Sea to Sumbawa river cruise in Borneo to observe the world’s largest 13 Badas, Sumbawa/Moyo Island 14 Komodo Island (Komodo National Park) population of orangutans and visit Komodo Island 15 Denpasar, Bali/Disembark ship/Depart Bali/ to see its fabled dragons. -

A Global Overview of Protected Areas on the World Heritage List of Particular Importance for Biodiversity

A GLOBAL OVERVIEW OF PROTECTED AREAS ON THE WORLD HERITAGE LIST OF PARTICULAR IMPORTANCE FOR BIODIVERSITY A contribution to the Global Theme Study of World Heritage Natural Sites Text and Tables compiled by Gemma Smith and Janina Jakubowska Maps compiled by Ian May UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre Cambridge, UK November 2000 Disclaimer: The contents of this report and associated maps do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP-WCMC or contributory organisations. The designations employed and the presentations do not imply the expressions of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP-WCMC or contributory organisations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or its authority, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION 1.0 OVERVIEW......................................................................................................................................................1 2.0 ISSUES TO CONSIDER....................................................................................................................................1 3.0 WHAT IS BIODIVERSITY?..............................................................................................................................2 4.0 ASSESSMENT METHODOLOGY......................................................................................................................3 5.0 CURRENT WORLD HERITAGE SITES............................................................................................................4 -

5- Informe ASEAN- Centre-1.Pdf

ASEAN at the Centre An ASEAN for All Spotlight on • ASEAN Youth Camp • ASEAN Day 2005 • The ASEAN Charter • Visit ASEAN Pass • ASEAN Heritage Parks Global Partnerships ASEAN Youth Camp hen dancer Anucha Sumaman, 24, set foot in Brunei Darussalam for the 2006 ASEAN Youth Camp (AYC) in January 2006, his total of ASEAN countries visited rose to an impressive seven. But he was an W exception. Many of his fellow camp-mates had only averaged two. For some, like writer Ha Ngoc Anh, 23, and sculptor Su Su Hlaing, 19, the AYC marked their first visit to another ASEAN country. Since 2000, the AYC has given young persons a chance to build friendships and have first hand experiences in another ASEAN country. A project of the ASEAN Committee on Culture and Information, the AYC aims to build a stronger regional identity among ASEAN’s youth, focusing on the arts to raise awareness of Southeast Asia’s history and heritage. So for twelve days in January, fifty young persons came together to learn, discuss and dabble in artistic collaborations. The theme of the 2006 AYC, “ADHESION: Water and the Arts”, was chosen to reflect the role of the sea and waterways in shaping the civilisations and cultures in ASEAN. Learning and bonding continued over visits to places like Kampung Air. Post-camp, most participants wanted ASEAN to provide more opportunities for young people to interact and get to know more about ASEAN and one another. As visual artist Willy Himawan, 23, put it, “there are many talented young people who could not join the camp but have great ideas Youthful Observations on ASEAN to help ASEAN fulfill its aims.” “ASEAN countries cooperate well.” Sharlene Teo, 18, writer With 60 percent of ASEAN’s population under the age of thirty, young people will play a critical role in ASEAN’s community-building efforts. -

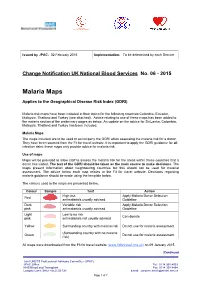

Change Notification No 06 2015

Northern Ireland BLOOD TRANSFUSION SERVICE Issued by JPAC: 02 February 2015 Implementation: To be determined by each Service Change Notification UK National Blood Services No. 06 - 2015 Malaria Maps Applies to the Geographical Disease Risk Index (GDRI) Malaria risk maps have been included in their topics for the following countries Colombia, Ecuador, Malaysia, Thailand and Turkey (see attached). Advice relating to use of these maps has been added to the malaria section of the preliminary pages as below. An update on the advice for Sri Lanka, Colombia, Malaysia, Thailand,and Turkey has been included. Malaria Maps The maps included are to be used to accompany the GDRI when assessing the malaria risk for a donor. They have been sourced from the Fit for travel website. It is important to apply the GDRI guidance for all infection risks; these maps only provide advice for malaria risk. Use of maps Maps will be provided to allow staff to assess the malaria risk for the areas within these countries that a donor has visited. The text of the GDRI should be taken as the main source to make decisions. The maps present information about neighbouring countries but this should not be used for malarial assessment. The advice below each map relates to the Fit for travel website. Decisions regarding malaria guidance should be made using the template below. The colours used in the maps are presented below. Colour Sample Text Action High risk Apply Malaria Donor Selection Red antimalarials usually advised Guideline Dark Variable risk Apply Malaria Donor -

Lorentz National Park Indonesia

LORENTZ NATIONAL PARK INDONESIA Lorentz National Park is the largest protected area in southeast Asia and one of the world’s last great wildernesses. It is the only tropical protected area to incorporate a continuous transect from snowcap to sea, and include wide lowland wetlands. The mountains result from the collision of two continental plates and have a complex geology with glacially sculpted peaks. The lowland is continually being extended by shoreline accretion. The site has the highest biodiversity in New Guinea and a high level of endemism. Threats to the site: road building, associated with forest die-back in the highlands, and increased logging and poaching in the lowlands. COUNTRY Indonesia NAME Lorentz National Park NATURAL WORLD HERITAGE SITE 1999: Inscribed on the World Heritage List under Natural Criteria viii, ix and x. STATEMENT OF OUTSTANDING UNIVERSAL VALUE [pending] The UNESCO World Heritage Committee issued the following statement at the time of inscription: Justification for Inscription The site is the largest protected area in Southeast Asia (2.35 mil. ha.) and the only protected area in the world which incorporates a continuous, intact transect from snow cap to tropical marine environment, including extensive lowland wetlands. Located at the meeting point of two colliding continental plates, the area has a complex geology with on-going mountain formation as well as major sculpting by glaciation and shoreline accretion which has formed much of the lowland areas. These processes have led to a high level of endemism and the area supports the highest level of biodiversity in the region. The area also contains fossil sites that record the evolution of life on New Guinea. -

The Gunung Leuser National Park Published by YAYASAN ORANGUTAN SUMATERA LESTARI- ORANGUTAN INFORMATION CENTRE (YOSL-OIC) Medan, Indonesia

Guidebook to The Gunung Leuser National Park Published by YAYASAN ORANGUTAN SUMATERA LESTARI- ORANGUTAN INFORMATION CENTRE (YOSL-OIC) Medan, Indonesia c 2009 by YOSL-OIC All rights reserved published in 2009 Suggested citation : Orangutan Information Centre (2009) Guidebook to The Gunung Leuser National Park. Medan. Indonesia ISBN 978-602-95312-0-6 Front cover photos : Sumatran Orangutan (Djuna Ivereigh), Rhinoceros Hornbill (Johan de Jong), Gunung Leuser National Park Forest (Adriano Almeira) Back cover photos : GLNP forest (Madeleine Hardus) The Orangutan Information Centre (OIC) is dedicated to the conservation of Sumatran orangutans (Pongo abelii) and their forest homes. Our grassroots projects in Sumatra work with local communities living alongside orangutan habitat. The OIC plants trees, visits schools and villages, and provides training to help local people work towards a more sustainable future. We are a local NGO staffed by Indonesian university graduates, believing that Sumatran people are best suited to have an impact in and help Sumatra. Phone / Fax: +62 61 4147142 Email: [email protected] Website: www.orangutancentre.org Acknowledgements Thanks are owed to many people who have been involved in the compilation and publication of this guidebook. First, our particular thanks go to James Thorn who spearheaded the writing and editing of this guidebook. David Dellatore and Helen Buckland from the Sumatran Orangutan Society also contributed; their patience and time during the reviewing and editing process reflects the professional expertise of this publication. We would like to thank to Suer Suryadi from the UNESCO Jakarta office, who has provided us with invaluable feedback, insights and suggestions for the improvement of this text. -

To Download the First Issue of the Hornbill Natural History & Conservation

IUCN HSG Hornbill Natural History and Conservation Volume 1, Number 1 Hornbill Specialist Group | January 2020 I PB IUCN HSG The IUCN SSC HSG is hosted by: Cover Photograph: Displaying pair of Von der Decken’s Hornbills. © Margaret F. Kinnaird II PB IUCN HSG Contents Foreword 1 Research articles Hornbill density estimates and fruit availability in a lowland tropical rainforest site of Leuser Landscape, Indonesia: preliminary data towards long-term monitoring 2 Ardiantiono, Karyadi, Muhammad Isa, Abdul Khaliq Hasibuan, Isma Kusara, Arwin, Ibrahim, Supriadi, and William Marthy Genetic monogamy in Von der Decken’s and Northern Red-billed hornbills 12 Margaret F. Kinnaird and Timothy G. O’Brien Long-term monitoring of nesting behavior and nesting habitat of four sympatric hornbill species in a Sumatran lowland tropical rainforest of Bukit Barisan Selatan National Park 17 Marsya C. Sibarani, Laji Utoyo, Ricky Danang Pratama, Meidita Aulia Danus, Rahman Sudrajat, Fahrudin Surahmat, and William Marthy Notes from the field Sighting records of hornbills in western Brunei Darussalam 30 Bosco Pui Lok Chan Trumpeter hornbill (Bycanistes bucinator) bill colouration 35 Hugh Chittenden Unusually low nest of Rufous-necked hornbill in Bhutan 39 Kinley, Dimple Thapa and Dorji Wangmo Flocking of hornbills observed in Tongbiguan Nature Reserve, Yunnan, China 42 Xi Zheng, Li-Xiang Zhang, Zheng-Hua Yang, and Bosco Pui Lok Chan Hornbill news Update from the Helmeted Hornbill Working Group 45 Anuj Jain and Jessica Lee IUCN HSG Update and Activities 48 Aparajita Datta and Lucy Kemp III PB IUCN HSG Foreword We are delighted and super pleased to an- We are very grateful for the time and effort put nounce the publication of the first issue of in by our Editorial Board in bringing out the ‘Hornbill Natural History and Conservation’.