Idps Rebuilding Lives Amid a Delicate Peace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

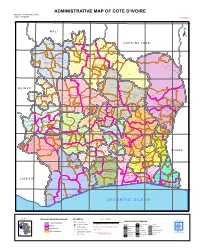

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP of COTE D'ivoire Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'ivoire 2Nd Edition

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF COTE D'IVOIRE Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'IVOIRE 2nd Edition 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W 11°0'0"N 11°0'0"N M A L I Papara Débété ! !. Zanasso ! Diamankani ! TENGRELA [! ± San Koronani Kimbirila-Nord ! Toumoukoro Kanakono ! ! ! ! ! !. Ouelli Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona ! ! Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko ! ! B U R K I N A F A S O !. Kouban Bougou ! Blésségué ! Sokoro ! Niéllé Tahara Tiogo !. ! ! Katogo Mahalé ! ! ! Solognougo Ouara Diawala Tienny ! Tiorotiérié ! ! !. Kaouara Sananférédougou ! ! Sanhala Sandrégué Nambingué Goulia ! ! ! 10°0'0"N Tindara Minigan !. ! Kaloa !. ! M'Bengué N'dénou !. ! Ouangolodougou 10°0'0"N !. ! Tounvré Baya Fengolo ! ! Poungbé !. Kouto ! Samantiguila Kaniasso Monogo Nakélé ! ! Mamougoula ! !. !. ! Manadoun Kouroumba !.Gbon !.Kasséré Katiali ! ! ! !. Banankoro ! Landiougou Pitiengomon Doropo Dabadougou-Mafélé !. Kolia ! Tougbo Gogo ! Kimbirila Sud Nambonkaha ! ! ! ! Dembasso ! Tiasso DENGUELE REGION ! Samango ! SAVANES REGION ! ! Danoa Ngoloblasso Fononvogo ! Siansoba Taoura ! SODEFEL Varalé ! Nganon ! ! ! Madiani Niofouin Niofouin Gbéléban !. !. Village A Nyamoin !. Dabadougou Sinémentiali ! FERKESSEDOUGOU Téhini ! ! Koni ! Lafokpokaha !. Angai Tiémé ! ! [! Ouango-Fitini ! Lataha !. Village B ! !. Bodonon ! ! Seydougou ODIENNE BOUNDIALI Ponondougou Nangakaha ! ! Sokoro 1 Kokoun [! ! ! M'bengué-Bougou !. ! Séguétiélé ! Nangoukaha Balékaha /" Siempurgo ! ! Village C !. ! ! Koumbala Lingoho ! Bouko Koumbolokoro Nazinékaha Kounzié ! ! KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Togoniéré ! Sirana -

République De Cote D'ivoire

R é p u b l i q u e d e C o t e d ' I v o i r e REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D'IVOIRE C a r t e A d m i n i s t r a t i v e Carte N° ADM0001 AFRIQUE OCHA-CI 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W Débété Papara MALI (! Zanasso Diamankani TENGRELA ! BURKINA FASO San Toumoukoro Koronani Kanakono Ouelli (! Kimbirila-Nord Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko (! Bougou Sokoro Blésségu é Niéllé (! Tiogo Tahara Katogo Solo gnougo Mahalé Diawala Ouara (! Tiorotiérié Kaouara Tienn y Sandrégué Sanan férédougou Sanhala Nambingué Goulia N ! Tindara N " ( Kalo a " 0 0 ' M'Bengué ' Minigan ! 0 ( 0 ° (! ° 0 N'd énou 0 1 Ouangolodougou 1 SAVANES (! Fengolo Tounvré Baya Kouto Poungb é (! Nakélé Gbon Kasséré SamantiguilaKaniasso Mo nogo (! (! Mamo ugoula (! (! Banankoro Katiali Doropo Manadoun Kouroumba (! Landiougou Kolia (! Pitiengomon Tougbo Gogo Nambonkaha Dabadougou-Mafélé Tiasso Kimbirila Sud Dembasso Ngoloblasso Nganon Danoa Samango Fononvogo Varalé DENGUELE Taoura SODEFEL Siansoba Niofouin Madiani (! Téhini Nyamoin (! (! Koni Sinémentiali FERKESSEDOUGOU Angai Gbéléban Dabadougou (! ! Lafokpokaha Ouango-Fitini (! Bodonon Lataha Nangakaha Tiémé Villag e BSokoro 1 (! BOUNDIALI Ponond ougou Siemp urgo Koumbala ! M'b engué-Bougou (! Seydougou ODIENNE Kokoun Séguétiélé Balékaha (! Villag e C ! Nangou kaha Togoniéré Bouko Kounzié Lingoho Koumbolokoro KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Koulokaha Pign on ! Nazinékaha Sikolo Diogo Sirana Ouazomon Noguirdo uo Panzaran i Foro Dokaha Pouan Loyérikaha Karakoro Kagbolodougou Odia Dasso ungboho (! Séguélon Tioroniaradougou -

Cote D'ivoire Operational Plan Report FY 2013

Approved Cote d'Ivoire Operational Plan Report FY 2013 Note: Italicized sections of narrative text indicate that the content was not submitted in the Lite COP year, but was derived from the previous Full COP year. This includes data in Technical Area Narratives, and Mechanism Overview and Budget Code narratives from continued mechanisms. Custom Page 1 of 354 FACTS Info v3.8.12.2 2014-01-14 08:08 EST Approved Operating Unit Overview OU Executive Summary Country Context Almost two years after the Ouattara administration came into office, Côte d'Ivoire is moving toward stability and growth, putting behind it more than 10 years of civil unrest that divided the country, impoverished the population, decimated health and social services. President Alassane Ouattara’s administration achieved a number of early successes in organizing national legislative elections, originating a new national development strategy, and reinvigorating the investment climate. The government’s efforts to foster economic growth, increase foreign investment, and improve infrastructure are producing results. Following a contraction of 4.7% in 2011, GDP rebounded remarkably, with growth of 8.5% in 2012 and initial IMF forecasts anticipating 8% growth in 2013. Only limited progress, however, has been achieved on national reconciliation efforts, accountability for crimes committed during the crisis years, and security sector reform. About half the population of 22 million survives on less than $2 a day; a similar proportion lives in rural areas with high illiteracy rates and poor access to services. According to the National Poverty Reduction Strategy (2009), the poverty rate worsened from 10% in 1985 to 48.9% in 2008. -

Ivory Coast: Administrative Structure

INFORMATION PAPER Ivory Coast – Administrative Structure The administrative structure of Ivory Coast1 was revised in September 2011. The new structure, which consists of 14 districts (2 autonomous districts and 12 regular districts) at first-order (ADM1) level, is as follows: ADM1 – 14 districts (2 autonomous districts and 12 regular districts) ADM2 – 31 regions (fra: région) ADM3 – 95 departments (fra: départment) ADM4 – 498 sub-prefectures (fra: sous-préfecture) Details of the ADM1s and ADM2s are provided on the next page. A map showing the administrative divisions can be found here: http://www.gouv.ci/doc/1333118154nouveau_decoupage_administrative_ci.pdf The previous structure, consisting of 19 regions at first-order level, was reorganised as follows: 1. The cities of Abidjan and Yamoussoukro were split from their regions (Lagunes and Lacs, respectively) to form autonomous districts. 2. The northern regions of Denguélé, Savanes, Vallée du Bandama, and Zanzan were re- designated as districts with no change in territory. 3. The old Agnéby and Lagunes regions, excluding Abidjan (see no. 1), merged to form Lagunes district. 4. Bafing and Worodougou regions merged to form Woroba district. 5. The department of Fresco was transferred from Sud-Bandama to Bas-Sassandra region to form Bas-Sassandra district; the remainder of Sud-Bandama region merged with Fromager to form Gôh-Djiboua district. 6. Dix-Huit Montagnes (18 Montagnes) and Moyen-Cavally regions merged to form Montagnes district. 7. Haut-Sassandra and Marahoué regions merged to form Sassandra-Marahoué district. 8. N'zi-Comoé and Lacs regions, excluding Yamoussoukro (see no. 1), merged to form Lacs district. 9. Moyen-Comoé and Sud-Comoé regions merged to form Comoé district. -

Cote D'ivoire

UNAIDS 2014 | REFERENCE CÔTE D’IVOIRE DEVELOPING SUBNATIONAL ESTIMATES OF HIV PREVALENCE AND THE NUMBER OF PEOPLE LIVING WITH HIV UNAIDS / JC2665E (English original, September 2014) Copyright © 2014. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). All rights reserved. Publications produced by UNAIDS can be obtained from the UNAIDS Information Production Unit. Reproduction of graphs, charts, maps and partial text is granted for educational, not-for-profit and commercial purposes as long as proper credit is granted to UNAIDS: UNAIDS + year. For photos, credit must appear as: UNAIDS/name of photographer + year. Reproduction permission or translation-related requests—whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution—should be addressed to the Information Production Unit by e-mail at: [email protected]. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNAIDS concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. UNAIDS does not warrant that the information published in this publication is complete and correct and shall not be liable for any damages incurred as a result of its use. METHODOLOGY NOTE Developing subnational estimates of HIV prevalence and the number of people living with HIV from survey data Introduction prevR Significant geographic variation in HIV Applying the prevR method to generate maps incidence and prevalence, as well as of estimates of the number of people living programme implementation, has been with HIV (aged 15–49 and 15 and older) and observed between and within countries. -

Côte D'ivoire, 2009

CÔTE D’IVOIRE: Land tensions are a major obstacle to durable solutions A profile of the internal displacement situation 30 December, 2009 This Internal Displacement Profile is automatically generated from the online IDP database of the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). It includes an overview of the internal displacement situation in the country prepared by the IDMC, followed by a compilation of excerpts from relevant reports by a variety of different sources. All headlines as well as the bullet point summaries at the beginning of each chapter were added by the IDMC to facilitate navigation through the Profile. Where dates in brackets are added to headlines, they indicate the publication date of the most recent source used in the respective chapter. The views expressed in the reports compiled in this Profile are not necessarily shared by the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. The Profile is also available online at www.internal-displacement.org. About the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, established in 1998 by the Norwegian Refugee Council, is the leading international body monitoring conflict-induced internal displacement worldwide. Through its work, the Centre contributes to improving national and international capacities to protect and assist the millions of people around the globe who have been displaced within their own country as a result of conflicts or human rights violations. At the request of the United Nations, the Geneva-based Centre runs an online database providing comprehensive information and analysis on internal displacement in some 50 countries. Based on its monitoring and data collection activities, the Centre advocates for durable solutions to the plight of the internally displaced in line with international standards. -

Côte D'ivoire

CÔTE D'IV OIRE - Reference Map Bagoe M A L I Dabélé B U R K I N A F A S O Banfora Manankoro Tingréla Niangoloko Gaoua Kimbirila Bolona Niélé Sankarani Kabangoué Mbengué Kaouara Zaguinaso Wa Nafadougou Boundiou Duangolodougou Samatigila Monongo Sépénédiokaha Bobanié DENGUELE Kimbirila Tiébila Morokodougou Varalé Badandougou Odoro Ferkessédougou Boundiali Bodonon Danoa Tarato Odienné Tiéme Koumbala Sikolo Niénesso Guémou Katiéré Korhogo Nasian Bouna Kébi Kanhasso SAVANES Kouroukouna Bou Blanc G U I N E A Bako Bandama Noumouso ZANZAN M araho Black Volta Niamotou u e C Ô T E D ' I V O I R E Banandje Niakaramandougou Koutouba Fadyadougou Lambira Beyla Koro Tienba Gonbodougou Kakpin Kani BAFING WORODOUGOU VALLEE DU BANDAMA Dépingo Laoudi-Ba Wongé Dabakala Touba Banzi Dagbaso Karpélé Dwalla Katiola Fouena Sorotona Nandala Bondoukou Séguéla Boukoro Tinbé Foungouésso Adohosou Aboua-Nguessankro Gombélé Soko Dioulassoba Koumahiri Nzérékoré Tevui Tanda Bouaké Bouroukro Goulaonfla Iréfla Lac de Bangofla Kossou Mbahiakro Ouaté Yéalé DIX-HUIT MONTAGNES Molonoublé Konézra M'Bahiacro Man Vavoua Danané Blaneu Sénikro Koun Sunyani Sanniquellie Bogouiné HAUT N'ZI COMOE Mbouédio Daoukro Bangolo SASSANDRA Niando Bouaflé LACS Bocanda Daloa Koitienkro Lolobo Bendékro Gregbe MARAHOUE Duékoué Aoussoukro Andé Abengourou Cavally Guézon Maigbé I YAMOUSSOUKRO Guibobli Banhiei Anikro Kotobi Tapéguhé MOYEN G H A N A Keibli Guiglo Oumé Dimbokro Attakro COMOE Issia MOYEN-CAVALLY FROMAGER Diégonéfla AGNEBY Zagne Gagnoa Pakobo Mbrimbo Tano Zwedru Kéibli Dibokin Barouyo -

Globalsign State List 1.9 WIP.Xlsx

GS States v1.8 AD 07 Andorra la Vella AD 02 Canillo AD 03 Encamp AD 08 Escaldes‐Engordany AD 04 La Massana AD 05 Ordino AD Principat d'Andorra AD 06 Sant Julià de Lòria AE AJ ‘Ajmān Ajman AE AZ Abū Z̧aby Abu Dhabi AE FU Al Fujayrah Fujairah AE SH Ash Shāriqah Sharjah AE DU Dubayy Dubai AE RK Ra’s al Khaymah Ras‐Al‐Khaimah, Ras Al Khaimah, Ras al‐Khaimah AE UQ Umm al Qaywayn AF BDS Badakhshān AF BDG Bādghīs AF BGL Baghlān AF BAL Balkh AF BAM Bāmyān AF DAY Dāykundī AF FRA Farāh AF FYB Fāryāb AF GHA Ghaznī AF GHO Ghōr AF HEL Helmand AF HER Herāt AF JOW Jowzjān AF KAB Kābul Kabul AF KAN Kandahār AF KAP Kāpīsā AF KHO Khōst AF KNR Kunar AF KDZ Kunduz AF LAG Laghmān AF LOG Lōgar AF NAN Nangarhār AF NIM Nīmrōz AF NUR Nūristān AF PIA Paktīā AF PKA Paktīkā AF PAN Panjshayr AF PAR Parwān AF SAM Samangān AF SAR Sar‐e Pul AF TAK Takhār AF URU Uruzgān AF WAR Wardak AF ZAB Zābul AG Antigua y Barbuda AG 10 Barbuda AG 11 Redonda AG 03 Saint George AG 04 Saint John's St John's, St. John's AG 05 Saint Mary AG 06 Saint Paul AG 07 Saint Peter AG 08 Saint Philip AL BR Berat AL BU Bulqizë AL Central Albania AL DL Delvinë AL DV Devoll AL DI Dibër AL DR Durrës AL EL Elbasan AL FR Fier AL GJ Gjirokastër AL GR Gramsh AL HA Has AL KA Kavajë AL ER Kolonjë AL KO Korçë AL KR Krujë AL KC Kuçovë AL KU Kukës AL KB Kurbin AL LE Lezhë AL LB Librazhd AL LU Lushnjë AL MM Malësi e Madhe AL MK Mallakastër AL MT Mat AL MR Mirditë AL PQ Peqin AL PR Përmet AL PG Pogradec AL PU Pukë AL SR Sarandë AL SH Shkodër AL SK Skrapar AL TE Tepelenë AL TR Tiranë AL TP Tropojë AL VL Vlorë -

Country Code Country Name Postal Code Formatting AF

Country Code Country Name Postal Code Formatting AF Afghanistan 9999 AX Aland Islands 99999 AL Albania 9999 DZ Algeria 99999 AS American Samoa 99999 AD Andorra AO Angola AI Anguilla AA-9999 AQ Antarctica 9999 AG Antigua and Barbuda AR Argentina A9999AAA AM Armenia 9999 AW Aruba AU Australia 9999 AT Austria 9999 AZ Azerbaijan AA 9999 BS Bahamas BH Bahrain 9999 BD Bangladesh 9999 BB Barbados AA99999 BY Belarus 999999 BE Belgium 9999 BZ Belize BJ Benin BM Bermuda AA 99 BT Bhutan 99999 BO Bolivia BQ Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba BA Bosnia and Herzegovina 99999 BW Botswana BV Bouvet Island BR Brazil 99999-999 IO British Indian Ocean Territory AA9A 9AA BN Brunei Darussalam AA9999 BG Bulgaria 9999 BF Burkina Faso BI Burundi KH Cambodia 99999 CM Cameroon CA Canada A9A 9A9 CV Cape Verde 9999 KY Cayman Islands AA9-9999 CF Central African Republic TD Chad CL Chile 9999999 CN China 999999 CX Christmas Island 9999 CC Cocos (Keeling) Islands 9999 A9 CO Colombia 999999 KM Comoros CG Congo CD Congo, DR CK Cook Islands CR Costa Rica 99999 HR Croatia 99999 CU Cuba 99999 CW Curacao CY Cyprus 9999 CZ Czech Republic 999 99 DK Denmark 9999 DJ Djibouti DM Dominica DO Dominican Republic 99999 EC Ecuador 999999 EG Egypt 99999 SV El Salvador 9999 GQ Equatorial Guinea ER Eritrea EE Estonia 99999 ET Ethiopia 9999 FK Falkland Islands AAAA 9AA FO Faroe Islands 999 FJ Fiji FI Finland 99999 FR France 99999 GF French Guiana 99999 PF French Polynesia 99999 TF French Southern Territories GA Gabon GM Gambia GE Georgia 9999 DE Germany 99999 GH Ghana GI Gibraltar AA99 9AA