Editor, Captain Scott B. Murray Editorial Assistant, Mr. Charles J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visual Smalltalk Enterprise ™ ™

Visual Smalltalk Enterprise ™ ™ Language Reference P46-0201-00 Copyright © 1999–2000 Cincom Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. Copyright © 1999–2000 Seagull Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. This product contains copyrighted third-party software. Part Number: P46-0201-00 Software Release 3.2 This document is subject to change without notice. RESTRICTED RIGHTS LEGEND: Use, duplication, or disclosure by the Government is subject to restrictions as set forth in subparagraph (c)(1)(ii) of the Rights in Technical Data and Computer Software clause at DFARS 252.227-7013. Trademark acknowledgments: CINCOM, CINCOM SYSTEMS, and the Cincom logo are registered trademarks of Cincom Systems, Inc. Visual Smalltalk is a trademark of Cincom Systems, Inc., its subsidiaries, or successors and are registered in the United States and other countries. Microsoft Windows is a registered trademark of Microsoft, Inc. Win32 is a trademark of Microsoft, Inc. OS/2 is a registered trademark of IBM Corporation. Other product names mentioned herein are used for identification purposes only, and may be trademarks of their respective companies. The following copyright notices apply to software that accompanies this documentation: Visual Smalltalk is furnished under a license and may not be used, copied, disclosed, and/or distributed except in accordance with the terms of said license. No class names, hierarchies, or protocols may be copied for implementation in other systems. This manual set and online system documentation copyright © 1999–2000 by Cincom Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of it may be copied, photocopied, reproduced, translated, or reduced to any electronic medium or machine-readable form without prior written consent from Cincom. -

Focal Point Custom Chart Plugin Reference Manual

Focal Point® Custom Chart Plugin Reference Manual 7.3.0 Publication information Trademarks December 2018 The following are trademarks or registered trademarks of UNICOM Systems, Inc. in the United States and/or other Information in this publication is subject to change. jurisdictions worldwide: Focal Point, UNICOM, Changes will be published in new editions or technical UNICOM Systems. newsletters. Documentation set The documentation relating to this product includes: ■ Focal Point Custom Chart Plugin Reference Manual Copyright notice Focal Point® (the Programs and associated materials) is a proprietary product of UNICOM Systems, Inc. – a division of UNICOM Global. The Programs have been provided pursuant to License Agreement containing restrictions on their use. The programs and associated materials contain valuable trade secrets and proprietary information of UNICOM Systems, Inc. and are protected by United States Federal and non-United States copyright laws. The Programs and associated materials may not be reproduced, copied, changed, stored, disclosed to third parties, and distributed in any form or media (including but not limited to copies on magnetic media) without the express prior written permission of UNICOM Systems, Inc., UNICOM Plaza Suite 310, 15535 San Fernando Mission Blvd., Mission Hills, CA 91345 USA. Focal Point® © Copyright 1997-2018 All Rights Reserved. UNICOM Systems, Inc. – a division of UNICOM Global. No part of this Program may be reproduced in any form or by electronic means, including the use of information storage and retrieval systems, without the express prior written consent and authorization of UNICOM Systems, Inc. No part of this manual may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without prior written permission from UNICOM Systems, Inc. -

Nested Class Modularity in Squeak/Smalltalk

Springer, Nested Class Modularity in Squeak/Smalltalk Nested Class Modularity in Squeak/Smalltalk Modularität mit geschachtelten Klassen in Squeak/Smalltalk by Matthias Springer A thesis submitted to the Hasso Plattner Institute at the University of Potsdam, Germany in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in ITSystems Engineering Supervisor Prof. Dr. Robert Hirschfeld Software Architecture Group Hasso Plattner Institute University of Potsdam, Germany August 17, 2015 Abstract We present the concept, the implementation, and an evaluation of Matriona, a module system for and written in Squeak/Smalltalk. Matriona is inspired by Newspeak and based on class nesting: classes are members of other classes, similarly to class instance variables. Top-level classes (modules) are globals and nested classes can be accessed using message sends to the corresponding enclosing class. Class nesting effec- tively establishes a global and hierarchical namespace, and allows for modular decomposition, resulting in better understandability, if applied properly. Classes can be parameterized, allowing for external configuration of classes, a form of dependency management. Furthermore, parameterized classes go hand in hand with mixin modularity. Mixins are a form of inter-class code reuse and based on single inheritance. We show how Matriona can be used to solve the problem of duplicate classes in different modules, to provide a versioning and dependency management mech- anism, and to improve understandability through hierarchical decomposition. v Zusammenfassung Diese Arbeit beschreibt das Konzept, die Implementierung und die Evaluierung von Matriona, einem Modulsystem für und entwickelt in Squeak/Smalltalk. Ma- triona ist an Newspeak angelehnt und basiert auf geschachtelten Klassen: Klassen, die, wie zum Beispiel auch klassenseitige Instanzvariablen, zu anderen Klassen gehören. -

Windowbuilder Pro/V 3.1

Cincom WindowBuilder Pro/V 3.1 P46-0208-00 Software to Simplify Our Complex World ® Copyright © 1999–2000 Cincom Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. Copyright © 1999–2000 Seagull Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. This product contains copyrighted third-party software. Part Number: P46-0208-00 Software Release 3.2 This document is subject to change without notice. RESTRICTED RIGHTS LEGEND: Use, duplication, or disclosure by the Government is subject to restrictions as set forth in subparagraph (c)(1)(ii) of the Rights in Technical Data and Computer Software clause at DFARS 252.227-7013. Trademark acknowledgments: CINCOM, CINCOM SYSTEMS, and the Cincom logo are registered trademarks of Cincom Systems, Inc. Visual Smalltalk is a trademark of Cincom Systems, Inc., its subsidiaries, or successors and are registered in the United States and other countries. Microsoft Windows is a registered trademark of Microsoft, Inc. Win32 is a trademark of Microsoft, Inc. OS/2 is a registered trademark of IBM Corporation. Other product names mentioned herein are used for identification purposes only, and may be trademarks of their respective companies. The following copyright notices apply to software that accompanies this documentation: Visual Smalltalk is furnished under a license and may not be used, copied, disclosed, and/or distributed except in accordance with the terms of said license. No class names, hierarchies, or protocols may be copied for implementation in other systems. This manual set and online system documentation copyright © 1999–2000 by Cincom Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of it may be copied, photocopied, reproduced, translated, or reduced to any electronic medium or machine-readable form without prior written consent from Cincom. -

Visualworks® Environment

Cincom Smalltalk DATA SHEET Cincom Smalltalk VisualWorks ® Environment Cincom Smalltalk is a pure, object-oriented application development suite for software developers who need to build applications quickly and efficiently. Cincom Smalltalk™ The Cincom Smalltalk product suite consists of two environments: VisualWorks and ObjectStudio ®. VisualWorks is an enterprise-class VisualWorks Environment application development and delivery platform used by world-class The VisualWorks suite is the companies in areas such as semiconductor manufacture, shipping, financial premier Smalltalk platform for risk management, insurance, banking, government, education and building instantly portable server, healthcare. web-based and client/server applications. VisualWorks is VisualWorks portable across a wide range of platforms: VisualWorks includes components for any type of work your team might contemplate: Web Applications, WS* (Web Services), SNMP Connectivity Windows (2000/XP/200x/Vista/CE and superior development tools. VisualWorks now includes best-of-breed • ARM and x86) tools like the Refactoring Browser and the Professional Debugger Package, Mac OS X PowerPC and Intel fully integrated with the product. VisualWorks is ready for integration with • Linux (x86/SPARC/PPC) other leading applications and services, with support for Web Services, • HPUX CORBA, COM and common internet protocols. • AIX VisualWorks has support for all major internet protocols including SOAP, • Solaris (SPARC/x86) • WSDL and UDDI. Additionally, VisualWorks supports interoperability standards such as SNMP and MQS, allowing Smalltalk applications to VisualWorks ® has full 64-bit support seamlessly plug into an enterprise infrastructure an important feature for IS on Linux (x86-64) and Solaris — shops that need to integrate multiple applications from multiple sources. (SPARC/x86-64). This generation of Smalltalk also stands as the best way to interoperate with Highlights the existing and competing standards of .NET and J2EE. -

Expanding the Visualworks Image

Expanding the VisualWorks Image After you install VisualWorks, the base Image (to be found in the subdirectory image in the installation directory1) contains packages or bundles with the standard classes that are needed for application development, along with those that contain the program code for the development environment. The subdirectory contributed contains several enhancements that are delivered with VisualWorks. Among these are • Frameworks for the most diverse programming tasks (for example, SUnitToo, a later version of SUnit2) • Components to access various database systems • Free versions of third-part software • Much more These enhancements are in the form of parcels. Stated somewhat simply, parcels are pack- ages that have been “exported” from an Image. You can use the menu item Package → Publish as Parcel to export a package as a parcel. This creates two files: <package-name>.pst <package-name>.pcl The file with the .pst extension contains the Smalltalk source code. The file with the .pcl extension contains the program translated into byte code. You can use the Parcel Manager, which is started by clicking the menu item System → Parcel Manager in the Launcher, to integrate parcels into one’s own Image. The Parcel Manager presents three views of the parcels from the contributed directory. 1See Fig. 5.1. 2See Chap. 15. © Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden 2015 419 J. Brauer, Programming Smalltalk – Object-Orientation from the Beginning, DOI 10.1007/978-3-658-06823-3 420 Expanding the VisualWorks Image Fig. A.1 The Parcel Manager 1. The parcels are grouped by theme in the Suggestions tab. In Fig. A.1, the parcel SunitTool(s) has been selected from the Popular directory (see Chap. -

Backing by Cincom

Cincom Smalltalk™ The perfect solution for delivering applications on time and under budget. Cincom SmalltalkTM Deliver Perfect Applications at the Speed of Thought Cincom Smalltalk is a cross-platform development Current Release Products and Services technology that helps developers quickly and efficiently build applications—from classic client/server systems to For four decades a market-leading development highly scalable web applications. language and in its second decade under Cincom leadership, Cincom Smalltalk is a rich set of application Cincom Smalltalk’s frameworks give you tactical and development environments and tools. Cincom Smalltalk strategic advantages over Java, Ruby, PHP, Eclipse, is ideally suited for users who need to build custom and Visual Studio, helping you develop software with applications to support complex, rapidly changing unparalleled productivity and fast reaction time, so you business requirements to meet urgent time-to-market deliver perfect applications at the speed of thought. needs. • ObjectStudio combines a native Windows environment with access to the extensive VisualWorks libraries. Cincom Smalltalk’s Value to You ObjectStudio delivers perfect Windows applications faster with a modeling tool that simplifies development ® With any of Cincom Smalltalk’s frameworks—ObjectStudio and design, and a mapping tool that simplifies storage ® for native Windows applications, VisualWorks for cross- and retrieval of data from the relational database, TM platform development, or Web Velocity for web enhances deployment, and speeds delivery time and applications—you get unparalleled productivity and fast ROI. ObjectStudio 8 is the first and only Smalltalk reaction time to changing business realities for tactical environment to receive Microsoft’s Vista certification. and strategic advantages over your competition. -

International Smalltalk Conference 2006

(DRAFT) International Smalltalk Conference - Prague 2006 International Smalltalk Conference 2006 Editor Dr. Wolfgang Demeuter DRAFT of Proceedings This document contains the versions submitted to the conference and that have been selected for the conference to be held in Prague from the 2 Sept – 8 Sept 2006. This is not the final version of the articles. PLEASE DO NOT DISTRIBUTE. (DRAFT) International Smalltalk Conference - Prague 2006 (DRAFT) International Smalltalk Conference - Prague 2006 International Smalltalk conference 2006 program committee Wolfgang De Meuter (PC Chair), Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium Dave Simmons, Smallscript Corporation, USA Noury Bouraqadi, Ecole des Mines de Douai, France Nathanael Schaerli, Google R&D, Zurich, Switzerland Andrew Black, Portland State University, USA Serge Stinckwich, Université de Caen, France Joseph Pelrine, MetaProg GmbH, Switzerland Alan Knight, Cincom, USA Thomas Kuehne, Technische Universität Darmstadt, Germany, Christophe Roche, Université de Savoie, France, Maja D'Hondt, Université des Sciences et Technologies de Lille, France, Maximo Prieto, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Argentina Brian Foote University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, USA Dave Thomas, Bedarra Research Labs, USA Gilad Bracha, SUN Java Software, USA Serge Demeyer, Universiteit Antwerpen, Belgium Pierre Cointe, Ecole de Mines de Nantes, France Michel Tillman, Real Software, Belgium, Tudor Girba, Universität Bern, Switzerland (DRAFT) International Smalltalk Conference - Prague 2006 Table of Contents Aspects, -

Trouble Tracker Operations Manual --

-- -- Trouble Tracker Operations Manual -- -- TO ORDER COPIES OF THIS DOCUMENT CALL: AT&T Customer Information Center 1 800 432-6600 In Canada: 1 800 255-1242 WRITE: AT&T Customer Information Center 2855 North Franklin Road P.O. Box 19901 Indianapolis, IN 46219 ORDER: Document No. AT&T 585-225-703, Comcode 107257859 Issue 3, March 1994 For more information about AT&T documents, see Business Communications Systems Publications Catalog (555-000-010). TRADEMARK NOTICE ACCULINK, ACCUMASTER, DATAKIT, Dataphone, DEFINITY, DIMENSION, and StarKeeper are registered trademarks of AT&T. AUDIX is a trademark of AT&T. UNIX is a registered trademark of UNIX System Laboratories, a subsidiary of AT&T, in the U.S. and other countries. DEC is a registered trademark of Digital Equipment Corporation. IBM and NetView are registered trademarks of International Business Machines Corporation. INFORMIX is a registered trademark of Informix Software, Inc. 1-2-3 and Lotus are registered trademarks of the Lotus Development Corporation. Microsoft, MS, MS-DOS, and Excel are registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation. Windows is a trademark of Microsoft Corporation. Net/MASTER is a trademark of CINCOM Systems, Inc. Silent Knight is a registered trademark of Weycross, Inc. EXCEL is a copyrighted software owned by Microsoft Corporation. MLINK is a copyrighted software owned by Corporate Microsystems, Inc. Pixie is a copyrighted software owned by Zenographics, Inc. NOTICE While reasonable efforts were made to ensure that the information in this document was complete and accurate at the time of printing, AT&T can assume no responsibility for any errors. Changes or corrections to the information contained in this document may be incorporated into future reissues. -

12Thesug Conference Conference

Monday, September 6 Room 211 9:00 Registration and Coffee 10.30 Welcome 11:00 Keynote: Dan Ingalls 12:30 Lunch 14:00 Research Track 15:30 Coffee break 16:00 Research Track Coffee break Evening ESUG General assembly Tuesday, September 7 Room 211 9:00 Alan Knight: Object-Relational Persistence in Smalltalk 9:30 Janko Mivsek: Smalltalk Web frameworks: a comparison of Aida/Web and Seaside ththth 10:00 Martin Kobetic: Cryptography for Smalltalkers 11121222 ESUG Conference 10:30 Coffee break 11:00 Frank Lesser: LSW - Vision-Smalltalk 11:30 Claus Gittinger: Smalltalk/X 12:00 Thomas Brey: Smalltalk-based Speech User Interfaces Köthen ( (AnhaltAnhaltAnhalt)))) ––– Germany 12:30 Lunch 14:00 Andrew Black: Abstract Interpretation for Dummies: September 5 to 112222,, 2004 Program Analysis without Tears 14:30 Maurice Rabb: Microlingua: A Tiny Real-Time Smalltalk Marten Feldtmann: Smalltalk on a Windows CE 15:00 15:30 Coffee break 16:00 ESUG Innovation Awards Demos Sponsored by: Founding GSUG 19:00 University Jazz with Gottfried Böttger in Villa Endraß, Köthen, Bärteichpromenade 28 sponsored by Anhalt University and Georg Heeg Georg Heeg eK Dortmund – Köthen – Zürich Friday, September 10 Wednesday, September 8 Room 211 Technical Track Room 241 Teachers day Room 211 9:00 Christian Haider: Migration from VSE to VW with Pollock 9:00 Keynote: Avi Bryant (Room 211) 9:30 Georg Gollmann : Gemstone 10:30 Coffee break 10:00 A.v.Os and T. Verwaart: A Smalltalk-based system for 11:00 Petr Stepanek : 11:00 Marcus Denker + Markus Gälli dynamic multi-context information processing GemStone vs. (German): Short Intro of Squeak 10:30 Coffee break Relational and the German Squeak 11:00 John McIntosh: Smalltalk Garbage Collectors Databases Association Squeak e.V . -

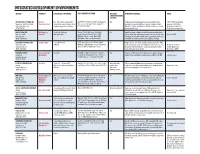

Integrated Development Environments

INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT ENVIRONMENTS VENDOR PRODUCT LANGUAGES SUPPORTED DEPLOYMENT PLATFORM INCLUDES OTHER KEY FEATURES PRICE CODE-VERSIONING SYSTEM? ACTIVESTATE SOFTWARE INC. Komodo Perl, PHP, Python, Ruby, XSLT; Any PHP, Perl, Python or Ruby-based applica- Yes Fully-integrated XSLT support, including an XSLT editor, $295; $495 bundled with Vancouver, British Columbia Professional 3.5.3 customizable context-aware editor tion server; client applications supported debugger and code intelligence. Komodo installs on Linux, one year of ActivePerl www.activestate.com supports many other languages through GUI builder Mac OS X, Solaris and Windows; all four platforms are includ- Profesional or ActiveTcl (778) 786-1114 ed with each license Professional subscription service BEA SYSTEMS INC. BEA Workshop Java, SOA, J2EE and Support for debugging and deployment Yes AppXRay creates a database of all the artifacts and their hierar- San Jose, Calif. Studio 3.0 Web applications requires Apache Jakarta Tomcat, BEA chy of relationships and interdependencies; benefits include code Starts at $899 www.bea.com WebLogic Server, Caucho Resin, IBM completion that reaches multiple levels, page variable names and (408) 570-8000 WebSphere, JBoss or Mortbay Jetty their fields, real-time consistency and validation checking BORLAND SOFTWARE CORP. Jbuilder 2006 Java J2EE 1.4 and J2EE application servers, including BEA Yes Eclipse-based; JSF, Struts and Web Services designers, UML Cupertino, Calif. JDK 5.0 WebLogic, IBM WebSphere, Sybase EAServer, code visualization, -

EGYPTIAN NATIONAL STI NETWORK USAID Contract NEB-0016-C-00

// DATABASE SOFTWARE SELECTION FOR THE EGYPTIAN NATIONAL STI NETWORK Vladimir Slamecka USAID Contract NEB-0016-C-00-2092-00 June 1q84 Georgia Institute of Technology Atlanta, Georgia Academy of Scienti f4 Research and Technology CaLro, Egypt ABSTRACT The study reports on the evaluation and selection of information/data management boftware for the Egyptian National Scientific and Technical (STI) Network. The network consists of sectorally oriented information service nodes (ISNs), each having a responsibility for the development and maintenance of public databases of Egyptian information and data. The report elaborates on the differences between information retrieval and database management (DBMS) systems, and concludes that while the Egyptian databases are likely to contain both unstructured text and structured numeric data, the former are likely to receive initial emphasis. From this premise the report lists the mandatory and desirable specifications of the database software. The evaluation methodology was comprised of an extensive, two-year survey of available commercial software and its evaluation against the mandatory specifications. The strategy of selecting a software package includec;, in the order of preference, a) a "universal" DBMS capable of handling both text and data types; b) a relational DBMS expandable to handling full-text retrieval; and c) an IR softwa:e system. After studying nearly 100 software packages it was concluded that no "universal" DBHS and no relational DBMS on the market meet the constraints and demands of the National STI Network of Egypt. The recommended software is the recently introduced mini/micro version of BRS/SEARCH, a full-text information management software package from BRS, Inc.