Identifying Handmade Lace Identification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lacemaking? No Way! You Have to Buy a Bunch of Equipme

Lacis Have you ever heard this (or said it): “Lacemaking? No way! You have to buy a bunch of equipment, learn a thousand stitches, and it takes a month of eyestrain to produce just an inch of lace!” How about this? “Handmade lace isn’t worth it; it tears up too easily, and it can’t be washed.” Or the Kiss of Death: “Lace isn’t appropriate to my time period.” Nonsense! What would you say if I told you that, for less than $20, and a weekend’s work, even a child can produce lace that is attractive and versatile, can survive repeated trips through the washing machine, and is appropriate for at least late 12th century through end of Period? Lacis is that lace. Lacis (also known as darned netting, filet lace, mezzo mandolino, and Filet Italien) is one of the oldest known lacemaking techniques. Examples of the netting itself – which even the most hardened Viking would recognize as simple fishnet -- has been found in ancient Egyptian tombs. Fine netting, delicately darned, have been found in sites dating back to the earliest days of the 14th century. It is mentioned specifically in the Ancrin Riwle (a novice nun’s ‘handbook,’ c. 1301), wherein the novice is admonished not to spend all her time netting, but to turn her hand to charitable works. Figure 1 pattern for bookmark Lacis is simply a net, such as fishnet, that has patterns darned into it. It comes in two basic categories, which categorize the kind of net used. Mondano is classic fishnet, a knotted netting where a shuttle and mesh gauge is used to make link loops together to form the net. -

Bobbin Lace You Need a Pattern Known As a Pricking

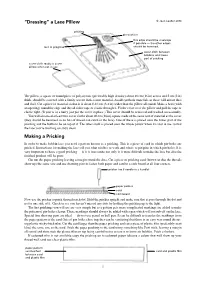

“Dressing” a Lace Pillow © Jean Leader 2014 pricking pin-cushion this edge should be a selvage if possible — the other edges lace in progress should be hemmed. cover cloth between bobbins and lower part of pricking cover cloth ready to cover pillow when not in use The pillow, a square or round piece of polystyrene (preferably high density) about 40 cm (16 in) across and 5 cm (2 in) thick, should be covered with a firmly woven dark cotton material. Avoid synthetic materials as these will attract dust and fluff. Cut a piece of material so that it is about 8-10 cm (3-4 in) wider than the pillow all round. Make a hem (with an opening) round the edge and thread either tape or elastic through it. Fit the cover over the pillow and pull the tape or elastic tight. (If you’re in a hurry just pin the cover in place.) This cover should be removed and washed occasionally. You will also need at least two cover cloths about 40 cm (16 in) square made of the same sort of material as the cover (they should be hemmed so no bits of thread can catch in the lace). One of these is placed over the lower part of the pricking and the bobbins lie on top of it. The other cloth is placed over the whole pillow when it is not in use so that the lace you’re working on stays clean. Making a Pricking In order to make bobbin lace you need a pattern known as a pricking. -

Bobbinwork Basics by Jill Danklefsen

SPECIAL CLASSROOM EDITION BOBBINWORK BASICS BY JILL DANKLEFSEN obbinwork is a technique that places heavy decorative 4. The type of stitch chosen as well as the type of “bobbin yarn” Bthreads on the surface of the fabric, sewn as machine-fed selected will dictate how loose the tension needs to be adjusted decorative stitches or as freemotion stitches. Typically, these on the bobbin case. threads, yarns, and cords are too large to fit through the eye of the sewing machine needle. So, in order to achieve a “stitched 5. Remember the rule of tension adjustment --“Righty, Tighty -- look”, you sew with the heavy decorative thread wound onto a Lefty, Loosey” bobbin and placed in the bobbin case of the machine. 6. Use a “construction quality” thread on the “topside” of your machine, as the needle tension will usually be increased. Think of the top thread as literally pulling the “bobbin yarn” into place to form the stitch pattern. 7. Bobbins can be wound by hand or by machine. Whenever possible, wind the bobbin using the bobbin winder mechanism on the machine. This will properly tension the “bobbin yarn” for a better stitch quality. 8. Bobbinwork can be sewn with the Feed dogs up or down. If stitching freemotion, a layer of additional stabilizer or the use of a machine embroidery hoop may be necessary. 9. Select the proper presser foot for the particular bobbinwork YARNS AND THREADS SUITABLE FOR BOBBINWORK technique being sewn. When working with the heavier “bobbin yarns”, the stitches produced will be thicker. Consider selecting • Yarns (thinner types, often a foot with a large indentation underneath it, such as Foot used for knitting machines) #20/#20C.This foot will ride over the stitching much better. -

Catalogue of the Famous Blackborne Museum Collection of Laces

'hladchorvS' The Famous Blackbome Collection The American Art Galleries Madison Square South New York j J ( o # I -legislation. BLACKB ORNE LA CE SALE. Metropolitan Museum Anxious to Acquire Rare Collection. ' The sale of laces by order of Vitail Benguiat at the American Art Galleries began j-esterday afternoon with low prices ranging from .$2 up. The sale will be continued to-day and to-morrow, when the famous Blackborne collection mil be sold, the entire 600 odd pieces In one lot. This collection, which was be- gun by the father of Arthur Blackborne In IS-W and ^ contmued by the son, shows the course of lace making for over 4(Xi ye^rs. It is valued at from .?40,fX)0 to $oO,0()0. It is a museum collection, and the Metropolitan Art Museum of this city would like to acciuire it, but hasnt the funds available. ' " With the addition of these laces the Metropolitan would probably have the finest collection of laces in the world," said the museum's lace authority, who has been studying the Blackborne laces since the collection opened, yesterday. " and there would be enough of much of it for the Washington and" Boston Mu- seums as well as our own. We have now a collection of lace that is probablv pqual to that of any in the world, "though other museums have better examples of some pieces than we have." Yesterday's sale brought SI. .350. ' ""• « mmov ON FREE VIEW AT THE AMERICAN ART GALLERIES MADISON SQUARE SOUTH, NEW YORK FROM SATURDAY, DECEMBER FIFTH UNTIL THE DATE OF SALE, INCLUSIVE THE FAMOUS ARTHUR BLACKBORNE COLLECTION TO BE SOLD ON THURSDAY, FRIDAY AND SATURDAY AFTERNOONS December 10th, 11th and 12th BEGINNING EACH AFTERNOON AT 2.30 o'CLOCK CATALOGUE OF THE FAMOUS BLACKBORNE Museum Collection of Laces BEAUTIFUL OLD TEXTILES HISTORICAL COSTUMES ANTIQUE JEWELRY AND FANS EXTRAORDINARY REGAL LACES RICH EMBROIDERIES ECCLESIASTICAL VESTMENTS AND OTHER INTERESTING OBJECTS OWNED BY AND TO BE SOLD BY ORDER OF MR. -

Powerhouse Museum Lace Collection: Glossary of Terms Used in the Documentation – Blue Files and Collection Notebooks

Book Appendix Glossary 12-02 Powerhouse Museum Lace Collection: Glossary of terms used in the documentation – Blue files and collection notebooks. Rosemary Shepherd: 1983 to 2003 The following references were used in the documentation. For needle laces: Therese de Dillmont, The Complete Encyclopaedia of Needlework, Running Press reprint, Philadelphia, 1971 For bobbin laces: Bridget M Cook and Geraldine Stott, The Book of Bobbin Lace Stitches, A H & A W Reed, Sydney, 1980 The principal historical reference: Santina Levey, Lace a History, Victoria and Albert Museum and W H Maney, Leeds, 1983 In compiling the glossary reference was also made to Alexandra Stillwell’s Illustrated dictionary of lacemaking, Cassell, London 1996 General lace and lacemaking terms A border, flounce or edging is a length of lace with one shaped edge (headside) and one straight edge (footside). The headside shaping may be as insignificant as a straight or undulating line of picots, or as pronounced as deep ‘van Dyke’ scallops. ‘Border’ is used for laces to 100mm and ‘flounce’ for laces wider than 100 mm and these are the terms used in the documentation of the Powerhouse collection. The term ‘lace edging’ is often used elsewhere instead of border, for very narrow laces. An insertion is usually a length of lace with two straight edges (footsides) which are stitched directly onto the mounting fabric, the fabric then being cut away behind the lace. Ocasionally lace insertions are shaped (for example, square or triangular motifs for use on household linen) in which case they are entirely enclosed by a footside. See also ‘panel’ and ‘engrelure’ A lace panel is usually has finished edges, enclosing a specially designed motif. -

Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Identification

Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace DATS in partnership with the V&A DATS DRESS AND TEXTILE SPECIALISTS 1 Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Text copyright © Jeremy Farrell, 2007 Image copyrights as specified in each section. This information pack has been produced to accompany a one-day workshop of the same name held at The Museum of Costume and Textiles, Nottingham on 21st February 2008. The workshop is one of three produced in collaboration between DATS and the V&A, funded by the Renaissance Subject Specialist Network Implementation Grant Programme, administered by the MLA. The purpose of the workshops is to enable participants to improve the documentation and interpretation of collections and make them accessible to the widest audiences. Participants will have the chance to study objects at first hand to help increase their confidence in identifying textile materials and techniques. This information pack is intended as a means of sharing the knowledge communicated in the workshops with colleagues and the public. Other workshops / information packs in the series: Identifying Textile Types and Weaves 1750 -1950 Identifying Printed Textiles in Dress 1740-1890 Front cover image: Detail of a triangular shawl of white cotton Pusher lace made by William Vickers of Nottingham, 1870. The Pusher machine cannot put in the outline which has to be put in by hand or by embroidering machine. The outline here was put in by hand by a woman in Youlgreave, Derbyshire. (NCM 1912-13 © Nottingham City Museums) 2 Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Contents Page 1. List of illustrations 1 2. Introduction 3 3. The main types of hand and machine lace 5 4. -

Needle Arts 3 11628.Qxd

NEEDLE ARTS 3 PACK 11628 • 20 DESIGNS NX670 Flowered Hat Pins NX671 Handmade With Love By NX672 Sewing Bobbin Machine NX673 Rotary Cutter 2.11 X 3.89 in. 3.10 X 2.80 in. 2.49 X 2.50 in. 3.89 X 1.74 in. 53.59 X 98.81 mm 78.74 X 71.12 mm 63.25 X 63.50 mm 98.81 X 44.20 mm 4,587 St. 11,536 St. 10,818 St. 10,690 St. NX674 Dressmaker’s Shears NX675 Thread NX676 Sewing Border NX677 Tracing Wheel 3.89 X 1.88 in. 2.88 X 3.89 in. 5.00 X 2.19 in. 3.46 X 1.74 in. 98.81 X 47.75 mm 73.15 X 98.81 mm 127.00 X 55.63 mm 87.88 X 44.20 mm 7,892 St. 15,420 St. 16,465 St. 3,282 St. NX678 Sewing Angel NX679 Tomato Pincushion NX680 Measuring Tape NX681 Sewing Kit 3.76 X 3.21 in. 3.59 X 3.76 in. 3.69 X 1.78 in. 3.89 X 3.67 in. 95.50 X 81.53 mm 91.19 X 95.50 mm 93.73 X 45.21 mm 98.81 X 93.22 mm 20,593 St. 16,556 St. 8,410 St. 22,777 St. NX682 Iron & Ironing Board NX683 Sewing Machine Needle NX684 Needle Thread NX685 Embroidery Scissors 3.79 X 1.40 in. 1.57 X 2.89 in. 1.57 X 3.10 in. 3.00 X 2.58 in. -

The Oak Interior, 24 & 25 April 2013, Chester

Bonhams New House 150 Christleton Road Chester CH3 5TD +44 (0) 1244 313936 +44 (0) 1244 340028 fax 21122 The Oak Interior, 24 & 25 April 2013, Chester 2013, April 24 & 25 The Oak Interior including The E. Hopwell Collection Wednesday 24 April 2013 at 10am Thursday 25 April 2013 at 10am Chester The Oak Interior including The E. Hopwell Collection, Pewter and Textiles Wednesday 24 April 2013 at 10am Thursday 25 April 2013 at 10am Chester Bonhams Enquiries Sale Number: 21122 Please see back of catalogue New House for important notice to bidders 150 Christleton Road Day I Catalogue: £20 (£25 by post) Chester CH3 5TD Pewter Illustrations bonhams.com David Houlston Customer Services Back cover: Lot 496 +44 (0) 1244 353 119 Monday to Friday 8.30am to 6pm Inside front cover: Lot 265 Viewing [email protected] +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Inside back cover: Lot 289 Friday 19 April 10am to 4pm Sunday 21 April 11am to 2pm The E. Hopwell Collection of Monday 22 April 10am to 4pm Metalware & Treen Tuesday 23 April 10am to 4pm Megan Wheeler Wednesday 24 April 8.30am to 4pm +44 (0) 1244 353 127 Thursday 25 April 8.30am to 9.45am [email protected] Bids Textiles +44 (0) 20 7447 7448 Claire Browne +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax +44 (0) 1564 732 969 To bid via the internet [email protected] please visit www.bonhams.com Day II Please note that bids should be Furniture submitted no later than 24 hours David Houlston before the sale. -

The Lacenews Chanel on Youtube October 2011 Update

The LaceNews Chanel on YouTube October 2011 Update http://www.youtube.com/user/lacenews Bobbinlace Instruction - 1 (A-H) 1 1 Preparing bobbins for lace making achimwasp 10/14/2007 music 2 2 dentelle.mpg AlainB13 10/19/2010 silent 3 3 signet.ogv AlainB13 4/23/2011 silent 4 4 napperon.ogv AlainB13 4/24/2011 silent 5 5 Evolution d'un dessin technique d'une dentelle aux fuseaux AlainB13 6/9/2011 silent 6 6 il primo videotombolo alikingdogs 9/23/2008 Italian 7 7 1 video imparaticcio alikingdogs 11/14/2008 Italian 8 8 2 video imparaticcio punto tela alikingdogs 11/20/2008 Italian 9 9 imparaticcio mezzo punto alikingdogs 11/20/2008 Italian 10 10 Bolillos, Anaiencajes Hojas de guipur Blancaflor2776 4/20/2008 Spanish/Catalan 11 11 Bolillos, hojas de guipur Blancaflor2776 4/20/2008 silent 12 12 Bolillos, encaje 3 pares Blancaflor2776 6/26/2009 silent 13 13 Bobbin Lacemaking BobbinLacer 8/6/2008 English 14 14 Preparing Bobbins for Lace making BobbinLacer 8/19/2008 English 15 15 Update on Flower Project BobbinLacer 8/19/2008 English 16 16 Cómo hacer el medio punto - Encaje de bolillos canalsapeando 10/5/2011 Spanish 17 17 Cómo hacer el punto entero o punto de lienzo - Encaje de bolillos canalsapeando 10/5/2011 Spanish 18 18 Conceptos básicos - Encaje de bolillos canalsapeando 10/5/2011 Spanish 19 19 Materiales necesarios - Encaje de bolillos canalsapeando 10/5/2011 Spanish 20 20 Merletto a fuselli - Introduzione storica (I) casacenina 4/19/2011 Italian 21 21 Merletto a Fuselli - Corso: il movimento dei fuselli (III) casacenina 5/2/2011 Italian 22 -

Fashion in Paris; the Various Phases of Feminine Taste and Aesthetics from 1797 to 1897

EX LIBRIS Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration GIVEN BY The Hospital Book and News Socle IN 1900 FASHION IN PARIS THE VARIOUS PHASES OF FEMININE TASTE AND ESTHETICS FROM 1797 TO 1897=^ By OCTAVE UZANNE ^ from the French by LADY MARY LOYD ^ WITH ONE HUNDRED HAND- COLOURED PLATES fc? TWO HUNDRED AND FIFTY TEXT ILLUSTRATIONS BY FRANCOIS COURBOIN LONDON : WILLIAM HEINEMANN NEW YORK: CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS MDCCCXCVIII (pr V All rights reserved CHAP. PAGE I. The Close of the Eighteenth Century ... i Licentiousness of Dress and Habits under the Directory of the Nineteenth II. The Dawn Century . 23 The Fair Sex in the Tear VIII First Empire III. Under the ...... +5 Feminine Splendour in Court and City IV. Dress, Drawing - rooms, and Society under the Restoration ....... 65 1815-1825 V. The Fair Parisian in 1830 ..... 85 Manners, Customs, and Refme?nent of the Belles of the Romantic Period VI. Fashion and Fashion's Votaries, from 1840 to 1850 103 VII. Fashion's Panorama in 1850 . 115 The Tapageuses and the Myst'erieuses in under VIII. Life Paris the Second Empire . .127 Leaders of the Gay World, and Cocodettes IX. The Fair Sex and Fashions in General from 1870 till 1880 ....... 147 X. The Parisian, as She is . .165 Her Psychology, Her Tastes, Her Dress MM. kmmi X<3 INTRODUCTION he compilation of a complete bibliography, even the most concise, of the works devoted to the subject of Costume, T and to the incessant changes of Fashion at every period, and in every country, in the world, would be a considerable undertaking—a work worthy of such learning as dwelt in the monasteries of the sixteenth century. -

The Lure of Lace

Bobbin lace, probably Italian, from the mid to second half of the 16th century. 55cm x 3cm. Value £175. A border of bobbin lace. Honiton c1630. 106cm x 9cm. Value £500. Machine lace edging of parrots. Early 20th century. 25cm x 6cm. Border of bobbin lace, Flemish, c1660. 99cm x 8cm. Value £280. From the Jane Page Collection. The Lure of Lace by Brenda Greysmith Initially produced as a luxury for the wealthy, lace was made by hand for centuries in Europe and introduced into England about four hundred years ago. It was not until the industrialisation of the nineteenth century, that it became available to a less well-heeled Border of densely patterned needle lace, Dutch, mid 17th century. audience while still retaining immense charm. Throughout its long 58cm x 6cm. Value £480. history lace has been made in diverse materials. Linen, wool, gold and silver, silk and horsehair were all utilised before cotton came into use after 1820. Colours included white and ecru, black and polychrome, although the dyes used for these caused the thread to rot over time and little now remains. Hand-made lace was produced by two distinct methods. Bobbin lace is a miniature form of weaving made with numerous threads each wound onto a small handle of bone or wood. Needle lace is created with a needle and a single thread. The pattern is fastened to a backing fabric, foundation threads are couched down along the lines of the design and the motifs are then filled in with rows of buttonhole stitches. Among the many varieties of English bobbin lace are the Machine lace imitating Bedfordshire lace. -

Techniques Represented in Each Pattern

(updated) November 12, 2020 Dear Customer: Thank you for requesting information about my lace instruction and supply business. If you have any questions about the supplies listed on the following pages, let me use my 36 years of lacemaking experience to help you in your selections. My stock is expanding and changing daily, so if you don't see something you want please ask. It would be my pleasure to send promotional materials on any of the items you have questions about. Call us at (607) 277-0498 or visit our web page at: http://www.vansciverbobbinlace.com We would be delighted to hear from you at our email address [email protected]. All our orders go two day priority service. Feel free to telephone, email ([email protected]) or mail in your order. Orders for supplies will be filled immediately and will include a free catalogue update. Please include an 8% ($7.50 minimum to 1 lb., $10.50 over 1 lbs.-$12.00 maximum except for pillows and stands which are shipped at cost) of the total order to cover postage and packaging. New York State residents add sales tax applicable to your locality. Payment is by check, money order or credit card (VISA, MASTERCARD, DISCOVER) in US dollars. If you are looking for a teacher keep me in mind! I teach courses at all levels in Torchon, Bedfordshire, Lester, Honiton, Bucks Point lace, Russian and more! I am happy to tailor workshops to suit your needs. Check for scheduled workshops on the page facing the order form.