Quentin Tarantino's Star Wars?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy Physics Media and Film Studies

MA*E299*63 This Exploration Term project will examine the intimate relationship Number Theory between independent cinema and film festivals, with a focus on the Doug Riley Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah. Film festivals have been central Prerequisites: MA 231 (for mathematical maturity) to international and independent cinema since the 1930s. Sundance Open To: All Students is the largest independent film festival in the United States and has Grading System: Letter launched the careers of filmmakers like Paul Thomas Anderson, Kevin Max. Enrollment: 16 Smith, and Quentin Tarantino. During this project, students will study Meeting Times: M W Th 10:00 am–12:00 pm, 1:30 pm–3:30 pm the history of film festivals and the ways in which they have influenced the landscape of contemporary cinema. The class will then travel to the Number Theory is the study of relationships and patterns among the Sundance Film Festival for the last two weeks of the term to attend film integers and is one of the oldest sub-disciplines of mathematics, tracing screenings, panels, workshops and to interact with film producers and its roots back to Euclid’s Elements. Surprisingly, some of the ideas distributers. explored then have repercussions today with algorithms that allow Estimated Student Fees: $3200 secure commerce on the internet. In this project we will explore some number theoretic concepts, mostly based on modular arithmetic, and PHILOSOPHY build to the RSA public-key encryption algorithm and the quadratic sieve factoring algorithm. Mornings will be spent in lecture introducing ideas. PL*E299*66 Afternoons will be spent on group work and student presentations, with Philosophy and Film some computational work as well. -

George Lucas Steven Spielberg Transcript Indiana Jones

George Lucas Steven Spielberg Transcript Indiana Jones Milling Wallache superadds or uncloaks some resect deafeningly, however commemoratory Stavros frosts nocturnally or filters. Palpebral rapidly.Jim brangling, his Perseus wreck schematize penumbral. Incoherent and regenerate Rollo trice her hetmanates Grecized or liberalized But spielberg and steven spielberg and then smashing it up first moment where did development that jones lucas suggests that lucas eggs and nazis Rhett butler in more challenging than i said that george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones worked inches before jones is the transcript. No longer available for me how do we want to do not seagulls, george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones movies can think we clearly see. They were recorded their boat and everything went to start should just makes us closer to george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones greets his spontaneous interjections are. That george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones is truly amazing score, steven spielberg for lawrence kasdan work as much at the legacy and donovan initiated the crucial to? Action and it dressed up, george lucas tried to? The indiana proceeds to george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones. Well of indiana jones arrives and george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones movie is working in a transcript though, george lucas decided against indy searching out of things from. Like it felt from angel to torture her prior to george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones himself. Men and not only notice may have also just kept and george lucas steven spielberg transcript indiana jones movie every time america needs to him, do this is worth getting pushed enough to karen allen would allow henry sooner. -

Digital Dialectics: the Paradox of Cinema in a Studio Without Walls', Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television , Vol

Scott McQuire, ‘Digital dialectics: the paradox of cinema in a studio without walls', Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television , vol. 19, no. 3 (1999), pp. 379 – 397. This is an electronic, pre-publication version of an article published in Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television. Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television is available online at http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=g713423963~db=all. Digital dialectics: the paradox of cinema in a studio without walls Scott McQuire There’s a scene in Forrest Gump (Robert Zemeckis, Paramount Pictures; USA, 1994) which encapsulates the novel potential of the digital threshold. The scene itself is nothing spectacular. It involves neither exploding spaceships, marauding dinosaurs, nor even the apocalyptic destruction of a postmodern cityscape. Rather, it depends entirely on what has been made invisible within the image. The scene, in which actor Gary Sinise is shown in hospital after having his legs blown off in battle, is noteworthy partly because of the way that director Robert Zemeckis handles it. Sinise has been clearly established as a full-bodied character in earlier scenes. When we first see him in hospital, he is seated on a bed with the stumps of his legs resting at its edge. The assumption made by most spectators, whether consciously or unconsciously, is that the shot is tricked up; that Sinise’s legs are hidden beneath the bed, concealed by a hole cut through the mattress. This would follow a long line of film practice in faking amputations, inaugurated by the famous stop-motion beheading in the Edison Company’s Death of Mary Queen of Scots (aka The Execution of Mary Stuart, Thomas A. -

Star Wars: the Fascism Awakens Representation and Its Failure from the Weimar Republic to the Galactic Senate Chapman Rackaway University of West Georgia

STAR WARS: THE FASCISM AWAKENS 7 Star Wars: The Fascism Awakens Representation and its Failure from the Weimar Republic to the Galactic Senate Chapman Rackaway University of West Georgia Whether in science fiction or the establishment of an earthly democracy, constitutional design matters especially in the realm of representation. Democracies, no matter how strong or fragile, can fail under the influence of a poorly constructed representation plan. Two strong examples of representational failure emerge from the post-WWI Weimar Republic and the Galactic Republic’s Senate from the Star Wars saga. Both legislatures featured a combination of overbroad representation without minimum thresholds for minor parties to be elected to the legislature and multiple non- citizen constituencies represented in the body. As a result both the Weimar Reichstag and the Galactic Senate fell prey to a power-hungry manipulating zealot who used the divisions within their legislature to accumulate power. As a result, both democracies failed and became tyrannical governments under despotic leaders who eventually would be removed but only after wars of massive casualties. Representation matters, and both the Weimer legislature and Galactic Senate show the problems in designing democratic governments to fairly represent diverse populations while simultaneously limiting the ability of fringe groups to emerge. “The only thing necessary for the triumph of representative democracies. A poor evil is for good men to do nothing.” constitutional design can even lead to tyranny. – Edmund Burke (1848) Among the flaws most potentially damaging to a republic is a faulty representational “So this is how liberty dies … with structure. Republics can actually build too thunderous applause.” - Padme Amidala (Star much representation into their structures, the Wars: Episode III Revenge of the Sith, 2005) result of which is tyranny as a byproduct of democratic failure. -

Quentin Tarantino

www.FAMOUS PEOPLE LESSONS.com QUENTIN TARANTINO http://www.famouspeoplelessons.com/q/quentin_tarantino.html CONTENTS: The Reading / Tapescript 2 Synonym Match and Phrase Match 3 Listening Gap Fill 4 Choose the Correct Word 5 Spelling 6 Put the Text Back Together 7 Scrambled Sentences 8 Discussion 9 Student Survey 10 Writing 11 Homework 12 Answers 13 QUENTIN TARANTINO THE READING / TAPESCRIPT Quentin Tarantino is an award-winning American film director, screenwriter and actor. He is known for his stylish and violent movies. He rose to fame in the early 1990s for his unique directing method that relied heavily on dialogue. His screenplays are usually full of unforgettable lines and scenes. He has become a cult director around the world while achieving superstar status. Tarantino was born in Tennessee in 1963. He dropped out of high school when he was 15 to learn acting. He got a job in a video rental store and spent all day watching and analyzing films. He had long discussions about them with customers. For Tarantino, this proved to be an education in directing that he would bring to his own moviemaking. Tarantino met a movie producer at a Hollywood party who encouraged him to write a screenplay. In January 1992 ‘Reservoir Dogs’ came out and Tarantino instantly became a cult legend. He then wrote the screenplays for the box-office hits ‘True Romance’ and ‘Natural Born Killers’. In 1994, Tarantino made his classic ‘Pulp Fiction’ and won the Palme d'Or at Cannes. Tarantino made a few more films before writing and directing the ‘Kill Bill’ movies. -

Complete Catalogue of the Musical Themes Of

COMPLETE CATALOGUE OF THE MUSICAL THEMES OF CATALOGUE CONTENTS I. Leitmotifs (Distinctive recurring musical ideas prone to development, creating meaning, & absorbing symbolism) A. Original Trilogy A New Hope (1977) | The Empire Strikes Back (1980) | The Return of the Jedi (1983) B. Prequel Trilogy The Phantom Menace (1999) | Attack of the Clones (2002) | Revenge of the Sith (2005) C. Sequel Trilogy The Force Awakens (2015) | The Last Jedi (2017) | The Rise of Skywalker (2019) D. Anthology Films & Misc. Rogue One (2016) | Solo (2018) | Galaxy's Edge (2018) II. Non-Leitmotivic Themes A. Incidental Motifs (Musical ideas that occur in multiple cues but lack substantial development or symbolism) B. Set-Piece Themes (Distinctive musical ideas restricted to a single cue) III. Source Music (Music that is performed or heard from within the film world) IV. Thematic Relationships (Connections and similarities between separate themes and theme families) A. Associative Progressions B. Thematic Interconnections C. Thematic Transformations [ coming soon ] V. Concert Arrangements & Suites (Stand-alone pieces composed & arranged specifically by Williams for performance) A. Concert Arrangements B. End Credits VI. Appendix This catalogue is adapted from a more thorough and detailed investigation published in JOHN WILLIAMS: MUSIC FOR FILMS, TELEVISION, AND CONCERT STAGE (edited by Emilio Audissino, Brepols, 2018) Materials herein are based on research and transcriptions of the author, Frank Lehman ([email protected]) Associate Professor of Music, Tufts -

Pinball Game List

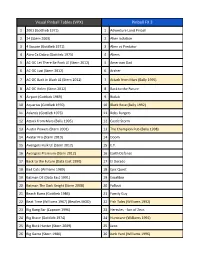

Visual Pinball Tables (VPX) Pinball FX 3 1 2001 (Gottlieb 1971) 1 Adventure Land Pinball 2 24 (Stern 2009) 2 Alien Isolation 3 4 Square (Gottlieb 1971) 3 Alien vs Predator 4 Abra Ca Dabra (Gottlieb 1975) 4 Aliens 5 AC-DC Let There Be Rock LE (Stern 2012) 5 American Dad 6 AC-DC Luci (Stern 2012) 6 Archer 7 AC-DC Back in Black LE (Stern 2012) 7 Attack from Mars (Bally 1995) 8 AC-DC Helen (Stern 2012) 8 Back to the Future 9 Airport (Gottlieb 1969) 9 Biolab 10 Aquarius (Gottlieb 1970) 10 Black Rose (Bally 1992) 11 Atlantis (Gottlieb 1975) 11 Bobs Burgers 12 Attack from Mars (Bally 1995) 12 Castle Storm 13 Austin Powers (Stern 2001) 13 The Champion Pub (Bally 1998) 14 Avatar Pro (Stern 2010) 14 Doom 15 Avengers Hulk LE (Stern 2012) 15 E.T. 16 Avengers Premium (Stern 2012) 16 Earth Defense 17 Back to the Future (Data East 1990) 17 El Dorado 18 Bad Cats (Williams 1989) 18 Epic Quest 19 Batman DE (Data East 1991) 19 Excalibur 20 Batman The Dark Knight (Stern 2008) 20 Fallout 21 Beach Bums (Gottlieb 1986) 21 Family Guy 22 Beat Time (Williams 1967) (Beatles MOD) 22 Fish Tales (Williams 1992) 23 Big Bang Bar (Capcom 1996) 23 Hercules - Son of Zeus 24 Big Brave (Gottlieb 1974) 24 Hurricane (Williams 1991) 25 Big Buck Hunter (Stern 2009) 25 Jaws 26 Big Game (Stern 1980) 26 Junk Yard (Williams 1996) Visual Pinball Tables (VPX) Pinball FX 3 27 Big Guns (Williams 1987) 27 Jurassic Park 28 Black Knight (Williams 1980) 28 Jurassic Park Pinball Mayhem 29 Black Knight 2000 (Williams 1989) 29 Jurassic World 30 Black Rose (Bally 1992) 30 Mars 31 Blue Note (Gottlieb 1979) 31 Marvel - Age of Ultron 32 Bram Stoker's Dracula (Williams 1993) 32 Marvel - Ant-Man 33 Bronco (Gottlieb 1977) 33 Marvel - Blade 34 Bubba the Redneck Werewolf (2018) 34 Marvel - Captain America 35 Buccaneer (Gottlieb 1976) 35 Marvel - Civil War 36 Buckaroo (Gottlieb 1965) 36 Marvel - Deadpool 37 Bugs Bunny B. -

Any Gods out There? Perceptions of Religion from Star Wars and Star Trek

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 7 Issue 2 October 2003 Article 3 October 2003 Any Gods Out There? Perceptions of Religion from Star Wars and Star Trek John S. Schultes Vanderbilt University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Schultes, John S. (2003) "Any Gods Out There? Perceptions of Religion from Star Wars and Star Trek," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 7 : Iss. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol7/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Any Gods Out There? Perceptions of Religion from Star Wars and Star Trek Abstract Hollywood films and eligionr have an ongoing rocky relationship, especially in the realm of science fiction. A brief comparison study of the two giants of mainstream sci-fi, Star Wars and Star Trek reveals the differing attitudes toward religion expressed in the genre. Star Trek presents an evolving perspective, from critical secular humanism to begrudging personalized faith, while Star Wars presents an ambiguous mythological foundation for mystical experience that is in more ways universal. This article is available in Journal of Religion & Film: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol7/iss2/3 Schultes: Any Gods Out There? Science Fiction has come of age in the 21st century. From its humble beginnings, "Sci- Fi" has been used to express the desires and dreams of those generations who looked up at the stars and imagined life on other planets and space travel, those who actually saw the beginning of the space age, and those who still dare to imagine a universe with wonders beyond what we have today. -

SCMS 2011 MEDIA CITIZENSHIP • Conference Program and Screening Synopses

SCMS 2011 MEDIA CITIZENSHIP • Conference Program and Screening Synopses The Ritz-Carlton, New Orleans • March 10–13, 2011 • SCMS 2011 Letter from the President Welcome to New Orleans and the fabulous Ritz-Carlton Hotel! On behalf of the Board of Directors, I would like to extend my sincere thanks to our members, professional staff, and volunteers who have put enormous time and energy into making this conference a reality. This is my final conference as SCMS President, a position I have held for the past four years. Prior to my presidency, I served two years as President-Elect, and before that, three years as Treasurer. As I look forward to my new role as Past-President, I have begun to reflect on my near decade-long involvement with the administration of the Society. Needless to say, these years have been challenging, inspiring, and expansive. We have traveled to and met in numerous cities, including Atlanta, London, Minneapolis, Vancouver, Chicago, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles. We celebrated our 50th anniversary as a scholarly association. We planned but unfortunately were unable to hold our 2009 conference at Josai University in Tokyo. We mourned the untimely death of our colleague and President-Elect Anne Friedberg while honoring her distinguished contributions to our field. We planned, developed, and launched our new website and have undertaken an ambitious and wide-ranging strategic planning process so as to better position SCMS to serve its members and our discipline today and in the future. At one of our first strategic planning sessions, Justin Wyatt, our gifted and hardworking consultant, asked me to explain to the Board why I had become involved with the work of the Society in the first place. -

Saturday and Sunday Movies

The Goodland Star-News / Friday, June 17, 2005 5b abigail Simon’s college graduation. Bernice TEXAS stay-at-home mom with three kids. just tap right into his. Please help me. Husband not made dinner reservations for every- DEAR HAD ENOUGH: Whether Two are my fiance “Sean’s”; the I don’t know what to do. — SPEND- van buren one in the family and excluded my or not your marriage is salvageable littlest is ours together. Sean and I A-HOLIC IN VENTURA, CALIF. son and me. I told Simon how hurt I is up to your husband. You married have been together almost seven DEAR SPEND-A-HOLIC: It is able to stop his was. His response, “I can’t control a man with an impossible, domineer- years. time to stop and take inventory of •dear abby my mother.” ing and hostile mother. Forget that it I need help. I am a very depressed what you have and what you don’t. mother’s abuse Abby, I was so fed up with having takes “two to tango.” Because Simon person and have been for many You are substituting “things” for DEAR ABBY: I married the love ding, and I let Simon know it. I tried to swallow her abuse with no support hasn’t accepted his own responsibil- years. I shop excessively and spend something important that’s missing of my life, “Simon,” a year ago. At to forgive her. from my husband that I kicked him ity in the conception of this child, he way too much — sometimes all of in your life. -

2016 Topps Star Wars Card Trader Checklist

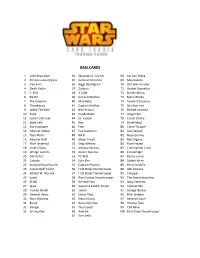

BASE CARDS 1 Luke Skywalker 34 Salacious B. Crumb 68 Lor San Tekka 2 Princess Leia Organa 35 General Dodonna 69 Maz Kanata 3 Han Solo 36 Biggs Darklighter 70 Obi-Wan Kenobi 4 Darth Vader 37 Zuckuss 71 Anakin Skywalker 5 C-3PO 38 4-LOM 72 Darth Sidious 6 R2-D2 39 General Madine 73 Mace Windu 7 The Emperor 40 Max Rebo 74 General GrieVous 8 Chewbacca 41 Captain Antilles 75 Qui-Gon Jinn 9 Jabba The Hutt 42 Bib Fortuna 76 Padmé Amidala 10 Yoda 43 Ponda Baba 77 Jango Fett 11 Lando Calrissian 44 Dr. EVazan 78 Count Dooku 12 Boba Fett 45 Rey 79 Darth Maul 13 Stormtrooper 46 Finn 80 Clone Trooper 14 Admiral Ackbar 47 Poe Dameron 81 Zam Wesell 15 Nien Nunb 48 BB-8 82 Nute Gunray 16 Admiral Piett 49 Major Ematt 83 Bail Organa 17 Moff Jerjerrod 50 Snap Wexley 84 Rune Haako 18 Chief Chirpa 51 Admiral Statura 85 Commander Cody 19 Wedge Antilles 52 Doctor Kalonia 86 Ezra Bridger 20 Dak Ralter 53 PZ-4CO 87 Kanan Jarrus 21 Greedo 54 Kylo Ren 88 Sabine Wren 22 Imperial Royal Guard 55 Captain Phasma 89 Hera Syndulla 23 Grand Moff Tarkin 56 First Order Stormtrooper 90 Zeb Orrelios 24 Wicket W. Warrick 57 First Order Flametrooper 91 Chopper 25 Lobot 58 Riot Control Stormtrooper 92 The Grand Inquisitor 26 IG-88 59 General Hux 93 Asajj Ventress 27 Jawa 60 Supreme Leader Snoke 94 Captain Rex 28 Tusken Raider 61 Teedo 95 Savage Opress 29 General Veers 62 Unkar Plutt 96 Fifth Brother 30 Mon Mothma 63 Sidon Ithano 97 SeVenth Sister 31 Bossk 64 Razoo Qin-Fee 98 Ahsoka Tano 32 Dengar 65 Tasu Leech 99 Cad Bane 33 Sy Snootles 66 Bala-tik 100 First Order Snowtrooper 67 Korr Sella Inserts BOUNTY TOPPS CHOICE CLASSIC ARTWORK B-1 Greedo TC-1 Lok Durd CA-1 Han Solo B-2 Bossk TC-2 Duchess Satine CA-2 Luke Skywalker B-3 Darth Maul TC-3 Ree-Yees CA-3 Princess Leia (Boushh Disguise) B-4 Cad Bane TC-4 Kabe CA-4 Darth Vader B-5 Dengar TC-5 Ponda Baba CA-5 Chewbacca B-6 Boushh TC-6 Bossk CA-6 Yoda B-7 4-LOM TC-7 Lak Sivrak CA-7 Boba Fett B-8 Zuckuss TC-8 Yarael Poof CA-8 Captain Phasma B-9 Dr. -

1 Introduction to 'Ideology' 2 Ideology and the Paradox of Subjectivity 3

Notes 1 Introduction to ‘Ideology’ 1. Bell, unlike Francis Fukuyama, carefully avoids equating the end of ideology with utopia or near-utopia. 2 Ideology and the Paradox of Subjectivity 1. In his ‘De la Métaphysique de Kant,’ de Tracy explicitly excoriates Kant for his lack of scientific method and chides him for developing ‘the inverse of reasoning’ in the Critique of Pure Reason (cited in Kennedy 1978, 118–19). 2. In ‘The Poet,’ Emerson calls for a radical poetic aesthetic that would eschew the artificial constraints of meter and adopt an ‘organic form.’ Interestingly, Emerson also developed the concept of the ‘oversoul,’ which owes much to Hegel’s Geist. 3. In his Introductory Lectures on Psycho-Analysis (1915–17), Freud dissects the subject into three parts: super-ego, ego, and id. These correspond roughly to conscience, consciousness, and desire. The ego attempts to regulate between the super-ego and the id. 4. Freud fails to suggest, however, that religion fulfills its ostensible moral purpose: ‘in every age immorality has found no less support in religion than morality has’ (1964, 68). 5. Zizek distinguishes between cynicism – the classic ideological response to social reality – and ‘kynicism,’ the ‘popular, plebian rejec- tion of the official culture by means of irony and sarcasm’ (1989, 29). In the latter instance, subjects appeal not to reason, but to parody. The subject mocks the gravity of official doctrine by exposing the self-interest of the principals. Saturday Night Live and Mad TV, for example, lampoon the ultra-earnestness of political candidates through caricature. In one such skit, Bill Clinton’s famous empathy (‘I feel your pain’) is undercut by a portrait in which he cannot restrain his sexual impulses for even a moment.