The Rhetoric of Alex Salmond and the 2014 Scottish Independence Referendum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spice Briefing

MSPs BY CONSTITUENCY AND REGION Scottish SESSION 1 Parliament This Fact Sheet provides a list of all Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) who served during the first parliamentary session, Fact sheet 12 May 1999-31 March 2003, arranged alphabetically by the constituency or region that they represented. Each person in Scotland is represented by 8 MSPs – 1 constituency MSPs: Historical MSP and 7 regional MSPs. A region is a larger area which covers a Series number of constituencies. 30 March 2007 This Fact Sheet is divided into 2 parts. The first section, ‘MSPs by constituency’, lists the Scottish Parliament constituencies in alphabetical order with the MSP’s name, the party the MSP was elected to represent and the corresponding region. The second section, ‘MSPs by region’, lists the 8 political regions of Scotland in alphabetical order. It includes the name and party of the MSPs elected to represent each region. Abbreviations used: Con Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party Green Scottish Green Party Lab Scottish Labour LD Scottish Liberal Democrats SNP Scottish National Party SSP Scottish Socialist Party 1 MSPs BY CONSTITUENCY: SESSION 1 Constituency MSP Region Aberdeen Central Lewis Macdonald (Lab) North East Scotland Aberdeen North Elaine Thomson (Lab) North East Scotland Aberdeen South Nicol Stephen (LD) North East Scotland Airdrie and Shotts Karen Whitefield (Lab) Central Scotland Angus Andrew Welsh (SNP) North East Scotland Argyll and Bute George Lyon (LD) Highlands & Islands Ayr John Scott (Con)1 South of Scotland Ayr Ian -

I Bitterly Regret the Day I Comgromised the Unity of My Party by Admitting

Scottish Government Yearbook 1990 FACTIONS, TENDENCIES AND CONSENSUS IN THE SNP IN THE 1980s James Mitchell I bitterly regret the day I comgromised the unity of my party by admitting the second member.< A work written over a decade ago maintained that there had been limited study of factional politics<2l. This is most certainly the case as far as the Scottish National Party is concerned. Indeed, little has been written on the party itself, with the plethora of books and articles which were published in the 1970s focussing on the National movement rather than the party. During the 1980s journalistic accounts tended to see debates and disagreements in the SNP along left-right lines. The recent history of the party provides an important case study of factional politics. The discussion highlights the position of the '79 Group, a left-wing grouping established in the summer of 1979 which was finally outlawed by the party (with all other organised factions) at party conference in 1982. The context of its emergence, its place within the SNP and the reaction it provoked are outlined. Discussion then follows of the reasons for the development of unity in the context of the foregoing discussion of tendencies and factions. Definitions of factions range from anthropological conceptions relating to attachment to a personality to conceptions of more ideologically based groupings within liberal democratic parties<3l. Rose drew a distinction between parliamentary party factions and tendencies. The former are consciously organised groupings with a membership based in Parliament and a measure of discipline and cohesion. The latter were identified as a stable set of attitudes rather than a group of politicians but not self-consciously organised<4l. -

1 Justice Committee Petition PE1370

Justice Committee Petition PE1370: Justice for Megrahi Written submission from Justice for Megrahi Ex-Scottish Government Ministers: Political Consequences of Public Statements On 28th June 2011 the Public Petitions Committee referred the Justice for Megrahi (JfM ) petition PE1370 to the Justice Committee for consideration. Its terms were as follows. ‘Calling on the Scottish Parliament to urge the Scottish Government to open an independent inquiry into the 2001 Kamp van Zeist conviction of Abdelbaset Ali Mohmed al-Megrahi for the bombing of Pan Am flight 103 in December 1988.’ The petition was first heard by the Justice Committee on 8th November 2011. On 6th June, 2013, as part of its consideration, the Justice Committee wrote to Kenny MacAskill MSP, then Cabinet Secretary for Justice, asking for the Government’s comments on our request for a public enquiry. In his reply of 24th June 2013, while acknowledging, that under the Inquiries Act 2005, the Scottish Ministers had the power to establish an inquiry, he concluded: ‘Any conclusions reached by an inquiry would not have any effect on either upholding or overturning the conviction as it is appropriately a court of law that has this power. In addition to the matters noted above, we would also note that Lockerbie remains a live on-going criminal investigation. In light of the above, the Scottish Government has no plans to institute an independent inquiry into the conviction of Mr Al-Megrahi.’ At this time Alex Salmond was the First Minister and with Mr MacAskill was intimately involved in the release of Mr Megrahi on 20th August 2009, a decision which caused worldwide controversy. -

Written Submission from Peter Murrell, Chief Executive, Scottish National Party, Dated 9 December, Following the Evidence Session on 8 December 2020

Written submission from Peter Murrell, Chief Executive, Scottish National Party, dated 9 December, following the evidence session on 8 December 2020 I undertook yesterday to forward Committee members the text of the email sent by Nicola Sturgeon on 27 August 2018. The email was sent to all members of the Scottish National Party, and the text is appended herewith. In addition, I've noticed some commentary this morning about what I said yesterday in response to questions about WhatsApp groups. I do not use WhatsApp. There are several messaging apps on my phone that I don’t use. This includes profiles on Facebook Messenger, LinkedIn, Instagram, Slack, Skype, and WhatsApp, none of which I use. I use my phone to make calls and to send emails and texts. Twitter is the only social media platform I’m active on. I trust the appended text and the above clarification is helpful to members. Best Peter PETER MURRELL Chief Executive Scottish National Party A statement from Nicola Sturgeon In recent days, calls have been made for the SNP to suspend Alex Salmond’s membership of the Party. As SNP leader, it is important that I set out the reasons for the Party’s current position as clearly as I can. The SNP, like all organisations, must act in accordance with due process. In this case, unlike in some previous cases, the investigation into complaints about Alex Salmond has not been conducted by the SNP and no complaints have been received by the Party. Also, for legal reasons, the limited information I have about the Scottish Government investigation cannot at this stage be shared with the Party. -

Report of the Committee on the Scottish Government Handling of Harassment Complaints

Published 23 March 2021 SP Paper 997 1st Report 2021 (Session 5) Committee on the Scottish Government Handling of Harassment Complaints Report of the Committee on the Scottish Government Handling of Harassment Complaints Published in Scotland by the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body. All documents are available on the Scottish For information on the Scottish Parliament contact Parliament website at: Public Information on: http://www.parliament.scot/abouttheparliament/ Telephone: 0131 348 5000 91279.aspx Textphone: 0800 092 7100 Email: [email protected] © Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliament Corporate Body The Scottish Parliament's copyright policy can be found on the website — www.parliament.scot Committee on the Scottish Government Handling of Harassment Complaints Report of the Committee on the Scottish Government Handling of Harassment Complaints, 1st Report 2021 (Session 5) Committee on the Scottish Government Handling of Harassment Complaints To consider and report on the actions of the First Minister, Scottish Government officials and special advisers in dealing with complaints about Alex Salmond, former First Minister, considered under the Scottish Government’s “Handling of harassment complaints involving current or former ministers” procedure and actions in relation to the Scottish Ministerial Code. [email protected] Committee on the Scottish Government Handling of Harassment Complaints Report of the Committee on the Scottish Government Handling of Harassment Complaints, 1st Report 2021 (Session 5) Committee -

Pdf, 649.7 Kb

Stands Scotland where she did? Scotland’s Journey back to statehood Joanna Cherry QC MP Wales Governance Centre Annual Lecture 27 November 2020 Noswaith dda. Thank you for inviting me to give this lecture. My pleasure at being asked has been tempered slightly by not getting the added bonus of a visit to Cardiff and Wales. But I hope that’s something that can be addressed when this pandemic is over or at least under control. And it’s great to be speaking at the end of a week when finally, there is light at the end of the tunnel thanks to the vaccines. My last trip to Wales was to give the fraternal address at the Plaid Cymru Spring 2018 conference in Llangollen. I greatly enjoyed the warmth and hospitality of my welcome. My only regret was that I was shamed by Liz Saville Roberts announcing to the whole conference that on the road trip up from London I and her other Scottish passenger had marred her usually healthy living habits by introducing her to the delights of Greggs pasties at one of the service station stops. It’s a great honour to be asked to give this speech. Since my election as an MP in 2015 I have benefited from the work of the centre and it’s been my pleasure to share platforms and select committee evidence sessions with Professors Richard Wynn Jones, Laura McAllister and Jo Hunt and to renew my acquaintance with Professor Daniel Wincott whom I first a long time ago when we were teenagers and he dated my best friend. -

The Brookings Institution

1 SCOTLAND-2013/04/09 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION SCOTLAND AS A GOOD GLOBAL CITIZEN: A DISCUSSION WITH FIRST MINISTER ALEX SALMOND Washington, D.C. Tuesday, April 9, 2013 PARTICIPANTS: Introduction: MARTIN INDYK Vice President and Director Foreign Policy The Brookings Institution Moderator: FIONA HILL Senior Fellow and Director Center on the United States and Europe The Brookings Institution Featured Speaker: ALEX SALMOND First Minister of Scotland * * * * * ANDERSON COURT REPORTING 706 Duke Street, Suite 100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Phone (703) 519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190 2 SCOTLAND-2013/04/09 P R O C E E D I N G S MR. INDYK: Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. Welcome to Brookings. I'm Martin Indyk, the Director of the Foreign Policy Program at Brookings, and we're delighted to have you here for a special event hosted by Center on the U.S. and Europe at Brookings. In an historic referendum set for autumn of next year, the people of Scotland will vote to determine if Scotland should become an independent country. And that decision will carry with it potentially far-reaching economic, legal, political, and security consequences for the United Kingdom. Needless to say, the debate about Scottish independence will be watched closely in Washington as well. And so we are delighted to have the opportunity to host the Right Honorable Alex Salmond, the first Minister of Scotland, to speak about the Scottish independence. He has been First Minister since 2007. Before that, he has had a distinguished parliamentary career. He was elected member of the UK parliament in 1987, served there until 2010. -

Survey Report

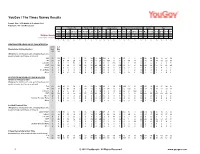

YouGov / The Times Survey Results Sample Size: 1100 Adults in Scotland (16+) Fieldwork: 4th - 8th March 2021 Vote in 2019 EU Ref 2016 Indy Ref Voting intention Holyrood Voting intention Gender Age Total Con Lab Lib Dem SNP Remain Leave Yes No Con Lab Lib Dem SNP Con Lab Lib Dem SNP Male Female 18-24 25-49 50-64 65+ Weighted Sample 1100 205 152 78 366 568 283 415 514 176 145 42 418 182 145 52 438 529 571 143 435 274 249 Unweighted Sample 1100 226 157 82 416 602 277 395 504 191 143 47 434 199 148 54 456 522 578 145 433 287 235 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % WESTMINSTER HEADLINE VOTING INTENTION 6-10 4-8 Westminster Voting Intention Nov Mar '20 '21 [Weighted by likelihood to vote, excluding those who would not vote, don't know, or refused] Con 19 23 84 7 8 1 17 40 4 40 100 0 0 0 93 6 3 0 25 20 12 16 27 32 Lab 17 17 5 64 20 5 19 16 8 27 0 100 0 0 3 88 11 2 16 18 18 15 20 19 Lib Dem 4 5 1 4 52 1 5 5 2 8 0 0 100 0 2 1 78 1 4 6 3 6 4 5 SNP 53 50 3 18 17 90 56 32 83 20 0 0 0 100 0 2 4 95 48 52 57 57 46 40 Green 3 3 0 6 3 2 3 0 1 2 0 0 0 0 0 2 2 2 3 3 6 4 1 2 Brexit Party 3 1 5 1 0 0 1 4 2 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 3 0 0 2 2 1 Other 1 1 2 0 0 0 0 2 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 1 3 1 0 1 HOLYROOD HEADLINE VOTING INTENTION Holyrood Voting Intention [Weighted by likelihood to vote, excluding those who would not vote, don't know, or refused] Con 19 22 80 6 18 1 18 38 4 39 93 3 10 0 100 0 0 0 25 19 13 17 24 31 Lab 15 17 10 59 15 4 17 18 8 26 5 87 4 1 0 100 0 0 17 16 14 14 20 18 Lib Dem 6 6 2 6 47 1 5 6 1 10 1 3 78 0 0 0 100 0 5 7 4 5 8 6 SNP 56 52 3 -

Members of Parliament from All Political Parties Support a Reduction in Tourism VAT

MP SUPPORTER LIST, AUTUMN/WINTER 2016-2017 Members of Parliament from all political parties support a reduction in tourism VAT Name Type Party Name Type Party Mr Alun Cairns MP Conservative Mr George Howarth MP Labour Mr Andrew Bingham MP Conservative Mr Gerald Jones MP Labour Mr Andrew Bridgen MP Conservative Mr Gordon Marsden MP Labour Mr Andrew Turner MP Conservative Mr Ian Austin MP Labour Ms Anne-Marie Morris MP Conservative Ms Jessica Morden MP Labour Mr Ben Howlett MP Conservative Mr Jim Cunningham MP Labour Mr Byron Davies MP Conservative Mr Jim Dowd MP Labour Ms Caroline Ansell MP Conservative Ms Jo Stevens MP Labour Mrs Caroline Spelman MP Conservative Mr Justin Madders MP Labour Ms Charlotte Leslie MP Conservative Ms Kate Hoey MP Labour Mr Chris Davies MP Conservative Ms Mary Glindon MP Labour Mr Christopher Pincher MP Conservative Mr Paul Flynn MP Labour Mr Conor Burns MP Conservative Mr Robert Flello MP Labour Mr Craig Williams MP Conservative Mr Roger Godsiff MP Labour Mr Craig Tracey MP Conservative Mr Ronnie Campbell MP Labour Mr David Nuttall MP Conservative Mr Stephen Hepburn MP Labour Mr David Jones MP Conservative Mr Steve Rotheram MP Labour Mr David Davis MP Conservative Mr Steven Kinnock MP Labour Mr David Morris MP Conservative Mr Tom Blenkinsop MP Labour Mr Geoffrey Cox MP Conservative Mr Virendra Sharma MP Labour Mr Geoffrey Clifton-Brown MP Conservative Ms Yasmin Qureshi MP Labour Mr George Freeman MP Conservative Mr Alistair Carmichael MP Liberal Democrat Sir Gerald Howarth MP Conservative Mr Greg Mulholland -

(Notification of Withdrawal) Bill

1 House of Commons NOTICES OF AMENDMENTS given up to and including Friday 27 January 2017 New Amendments handed in are marked thus Amendments which will comply with the required notice period at their next appearance Amendments tabled since the last publication: 18-41 and NC53 to NC97 COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE HOUSE EUROPEAN UNION (NOTIFICATION OF WITHDRAWAL) BILL NOTE This document includes all amendments tabled to date and includes any withdrawn amendments at the end. The amendments have been arranged in accordance with the European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Bill Programme Motion to be proposed by Secretary David Davis. NEW CLAUSES AND NEW SCHEDULES RELATING TO PARLIAMENTARY SCRUTINY OF THE PROCESS FOR THE UNITED KINGDOM’S WITHDRAWAL FROM THE EUROPEAN UNION Jeremy Corbyn Mr Nicholas Brown Keir Starmer Paul Blomfield Jenny Chapman Matthew Pennycook Mr Graham Allen Ian Murray Ann Clwyd Valerie Vaz Heidi Alexander Stephen Timms NC3 To move the following Clause— 2 Committee of the whole House: 27 January 2017 European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Bill, continued “Parliamentary oversight of negotiations Before issuing any notification under Article 50(2) of the Treaty on European Union the Prime Minister shall give an undertaking to— (a) lay before each House of Parliament periodic reports, at intervals of no more than two months on the progress of the negotiations under Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union; (b) lay before each House of Parliament as soon as reasonably practicable a copy in English of any document which the European Council or the European Commission has provided to the European Parliament or any committee of the European Parliament relating to the negotiations; (c) make arrangements for Parliamentary scrutiny of confidential documents.” Member’s explanatory statement This new clause establishes powers through which the UK Parliament can scrutinise the UK Government throughout the negotiations. -

Plaid Cymru and the SNP in Government

What does it mean to be ‘normal’? Plaid Cymru and the SNP in Government Craig McAngus School of Government and Public Policy University of Strathclyde McCance Building 16 Richmond Street Glasgow G1 1QX [email protected] Paper prepared for the Annual Conference of the Political Studies Association, Cardiff, 25 th -27 th March 2013 Abstract Autonomist parties have been described as having shifted from ‘niche to normal’. Governmental participation has further compounded this process and led to these parties facing the same ‘hard choices’ as other parties in government. However, the assumption that autonomist parties can now be described as ‘normal’ fails to address the residual ‘niche’ characteristics which will have an effect on the party’s governmental participation due to the existence of important ‘primary goals’. Taking a qualitative, comparative case study approach using semi-structured interview and documentary data, this paper will examine Plaid Cymru and the SNP in government. This paper argues that, although both parties can indeed be described as ‘normal’, the degree to which their ‘niche’ characteristics affect the interaction between policy, office and vote-seeking behaviour varies. Indeed, while the SNP were able to somewhat ‘detach’ their ‘primary goals’ from their government profile, Plaid Cymru’s ability to formulate an effective vote-seeking strategy was severely hampered by policy-seeking considerations. The paper concludes by suggesting that the ‘niche to normal’ framework requires two additional qualifications. Firstly, the idea that autonomist parties shift from ‘niche’ to ‘normal’ is too simplistic and that it is more helpful to examine how ‘niche’ characteristics interact with and affect ‘normal’ party status. -

15 May 2018 Nicola Sturgeon MSP First Minister of Scotland Leader of the Scottish National Party Dear First Minister, RE

62 Britton Street London, EC1M 5UY United Kingdom T +44 (0)203 422 4321 @privacyint www.privacyinternational.org 15 May 2018 Nicola Sturgeon MSP First Minister of Scotland Leader of the Scottish National Party Dear First Minister, RE: Self-regulation of voter targeting by political parties We are all concerned by the misuse of people’s data by technology giants and data analytics companies. At Privacy International, we work across the world to expose and minimize the democratic impact of such practices. Consequently, with the UK Data Protection Bill, we urged parliamentarians, through all the stages to delete the wide exemption, open to abuse, that allows political parties to process personal data ‘revealing political opinions’ for the purposes of their political activities. To no avail – this provision stays in the Bill. The recent revelations regarding misuse of our data by Cambridge Analytica, facilitated by Facebook has shown that our concerns are justified and the problem is systemic. Cambridge Analytica and Facebook are not alone. The use of data analytics in the political arena needs to be strictly regulated. Personal data that might not have previously revealed political opinions can now be used to infer such opinions (primarily through profiling). Failure to act can lead to political manipulation and risks undermining trust in the democratic process. We believe the Scottish National Party shares this concern. As Brendan O’Hara MP stated “… the days of the unregulated, self-policing, digital Wild-West, wherein giant tech companies and shadowy political organisations can harvest, manipulate, trade in and profit from the personal data of millions of innocent, unsuspecting people, could be coming to an end”.