Ungoverned Spaces: the Challenges of Governing Tribal Societies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Db List for 04-02-2020(Tuesday)

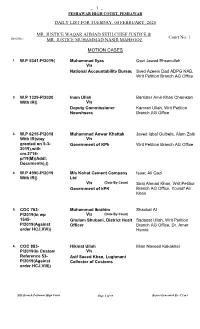

_ 1 _ PESHAWAR HIGH COURT, PESHAWAR DAILY LIST FOR TUESDAY, 04 FEBRUARY, 2020 MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH,CHIEF JUSTICE & Court No: 1 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE MUHAMMAD NASIR MAHFOOZ MOTION CASES 1. W.P 5341-P/2019() Muhammad Ilyas Qazi Jawad Ehsanullah V/s National Accountability Bureau Syed Azeem Dad ADPG NAB, Writ Petition Branch AG Office 2. W.P 1329-P/2020 Inam Ullah Barrister Amir Khan Chamkani With IR() V/s Deputy Commissioner Kamran Ullah, Writ Petition Nowshsera Branch AG Office 3. W.P 6215-P/2018 Muhammad Anwar Khattak Javed Iqbal Gulbela, Alam Zaib With IR(stay V/s granted on 5-3- Government of KPk Writ Petition Branch AG Office 2019),with cm.2715- p/19(M)(Addl: Documents),() 4. W.P 4990-P/2019 M/s Kohat Cement Company Isaac Ali Qazi With IR() Ltd V/s (Date By Court) Siraj Ahmad Khan, Writ Petition Government of kPK Branch AG Office, Yousaf Ali Khan 5. COC 763- Muhammad Ibrahim Shaukat Ali P/2019(in wp V/s (Date By Court) 1545- Ghulam Shubani, District Health Sadaqat Ullah, Writ Petition P/2019(Against Officer Branch AG Office, Dr. Amer order HCJ,XVI)) Hamid 6. COC 883- Hikmat Ullah Mian Naveed Kakakhel P/2019(in Custom V/s Reference 53- Asif Saeed Khan, Lughmani P/2019(Against Collector of Customs order HCJ,VIII)) MIS Branch,Peshawar High Court Page 1 of 88 Report Generated By: C f m i s _ 2 _ DAILY LIST FOR TUESDAY, 04 FEBRUARY, 2020 MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH,CHIEF JUSTICE & Court No: 1 BEFORE:- MR. -

Resettlement Policy Framework

Khyber Pass Economic Corridor (KPEC) Project (Component II- Economic Corridor Development) Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Resettlement Policy Framework Public Disclosure Authorized Peshawar Public Disclosure Authorized March 2020 RPF for Khyber Pass Economic Corridor Project (Component II) List of Acronyms ADB Asian Development Bank AH Affected household AI Access to Information APA Assistant Political Agent ARAP Abbreviated Resettlement Action Plan BHU Basic Health Unit BIZ Bara Industrial Zone C&W Communication and Works (Department) CAREC Central Asian Regional Economic Cooperation CAS Compulsory acquisition surcharge CBN Cost of Basic Needs CBO Community based organization CETP Combined Effluent Treatment Plant CoI Corridor of Influence CPEC China Pakistan Economic Corridor CR Complaint register DPD Deputy Project Director EMP Environmental Management Plan EPA Environmental Protection Agency ERRP Emergency Road Recovery Project ERRRP Emergency Rural Road Recovery Project ESMP Environmental and Social Management Plan FATA Federally Administered Tribal Areas FBR Federal Bureau of Revenue FCR Frontier Crimes Regulations FDA FATA Development Authority FIDIC International Federation of Consulting Engineers FUCP FATA Urban Centers Project FR Frontier Region GeoLoMaP Geo-Referenced Local Master Plan GoKP Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa GM General Manager GoP Government of Pakistan GRC Grievances Redressal Committee GRM Grievances Redressal Mechanism IDP Internally displaced people IMA Independent Monitoring Agency -

08 July 2021, Is Enclosed at Annex A

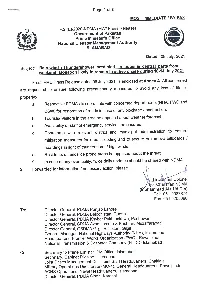

Page 1 of3 MOST IMMEDIATE/BY FAX F.2 (E)/2020-NDMA (MW/ Press Release) Government of Pakistan Prime Minister's Office National Disaster Management Authority ISLAMABAD NDMA Dated: 08 July, 2021 Subject: Rain-wind / Thundershower predicted in upper & central parts from weekend (Monsoon likely to remain in active phase during 10-14 July 2021 concerned Fresh PMD Press Release dated 08 July 2021, is enclosed at Annex A. All measures to avoid any loss of life or are requested to ensure following precautionary property: FWO and a. Respective PDMAs to coordinate with concerned departments (NHA, obstruction. C&W) for restoration of roads in case of any blockage/ . Tourists/Visitors in the area be apprised about weather forecast C. Availability of staff of emergency services be ensured. Coordinate with relevant district and municipal administration to ensure d. mitigation measures for urban flooding and to secure or remove billboards/ hoardings in light of thunderstorm/ high winds the threat. e. Residents of landslide prone areas be apprised about In case of any eventuality, twice daily updates should be shared with NDMA. f. 2 Forwarded for information / necessary action, please. Lieutenant Colonel For Chainman NDMA (Muhammad Ala Ud Din) Tel: 051-9087874 Fax: 051 9205086 To Director General, PDMA Punjab Lahore Director General, PDMA Balochistan, Quetta Director General, PDMA Khyber Pukhtunkhwa, Peshawar Director General, SDMA Azad Jammu & Kashmir, Muzaffarabad Director General, GBDMA Gilgit Baltistan, Gilgit General Manager, National Highways Authority -

Politics of Nawwab Gurmani

Politics of Accession in the Undivided India: A Case Study of Nawwab Mushtaq Gurmani’s Role in the Accession of the Bahawalpur State to Pakistan Pir Bukhsh Soomro ∗ Before analyzing the role of Mushtaq Ahmad Gurmani in the affairs of Bahawalpur, it will be appropriate to briefly outline the origins of the state, one of the oldest in the region. After the death of Al-Mustansar Bi’llah, the caliph of Egypt, his descendants for four generations from Sultan Yasin to Shah Muzammil remained in Egypt. But Shah Muzammil’s son Sultan Ahmad II left the country between l366-70 in the reign of Abu al- Fath Mumtadid Bi’llah Abu Bakr, the sixth ‘Abbasid caliph of Egypt, 1 and came to Sind. 2 He was succeeded by his son, Abu Nasir, followed by Abu Qahir 3 and Amir Muhammad Channi. Channi was a very competent person. When Prince Murad Bakhsh, son of the Mughal emperor Akbar, came to Multan, 4 he appreciated his services, and awarded him the mansab of “Panj Hazari”5 and bestowed on him a large jagir . Channi was survived by his two sons, Muhammad Mahdi and Da’ud Khan. Mahdi died ∗ Lecturer in History, Government Post-Graduate College for Boys, Dera Ghazi Khan. 1 Punjab States Gazetteers , Vol. XXXVI, A. Bahawalpur State 1904 (Lahore: Civil Military Gazette, 1908), p.48. 2 Ibid . 3 Ibid . 4 Ibid ., p.49. 5 Ibid . 102 Pakistan Journal of History & Culture, Vol.XXV/2 (2004) after a short reign, and confusion and conflict followed. The two claimants to the jagir were Kalhora, son of Muhammad Mahdi Khan and Amir Da’ud Khan I. -

Living Under Drones Death, Injury, and Trauma to Civilians from US Drone Practices in Pakistan

Fall 08 September 2012 Living Under Drones Death, Injury, and Trauma to Civilians From US Drone Practices in Pakistan International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clinic Stanford Law School Global Justice Clinic http://livingunderdrones.org/ NYU School of Law Cover Photo: Roof of the home of Faheem Qureshi, a then 14-year old victim of a January 23, 2009 drone strike (the first during President Obama’s administration), in Zeraki, North Waziristan, Pakistan. Photo supplied by Faheem Qureshi to our research team. Suggested Citation: INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS AND CONFLICT RESOLUTION CLINIC (STANFORD LAW SCHOOL) AND GLOBAL JUSTICE CLINIC (NYU SCHOOL OF LAW), LIVING UNDER DRONES: DEATH, INJURY, AND TRAUMA TO CIVILIANS FROM US DRONE PRACTICES IN PAKISTAN (September, 2012) TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I ABOUT THE AUTHORS III EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS V INTRODUCTION 1 METHODOLOGY 2 CHALLENGES 4 CHAPTER 1: BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT 7 DRONES: AN OVERVIEW 8 DRONES AND TARGETED KILLING AS A RESPONSE TO 9/11 10 PRESIDENT OBAMA’S ESCALATION OF THE DRONE PROGRAM 12 “PERSONALITY STRIKES” AND SO-CALLED “SIGNATURE STRIKES” 12 WHO MAKES THE CALL? 13 PAKISTAN’S DIVIDED ROLE 15 CONFLICT, ARMED NON-STATE GROUPS, AND MILITARY FORCES IN NORTHWEST PAKISTAN 17 UNDERSTANDING THE TARGET: FATA IN CONTEXT 20 PASHTUN CULTURE AND SOCIAL NORMS 22 GOVERNANCE 23 ECONOMY AND HOUSEHOLDS 25 ACCESSING FATA 26 CHAPTER 2: NUMBERS 29 TERMINOLOGY 30 UNDERREPORTING OF CIVILIAN CASUALTIES BY US GOVERNMENT SOURCES 32 CONFLICTING MEDIA REPORTS 35 OTHER CONSIDERATIONS -

Europe Report, Nr. 153: Pan-Albanianism

PAN-ALBANIANISM: HOW BIG A THREAT TO BALKAN STABILITY? 25 February 2004 Europe Report N°153 Tirana/Brussels TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 A. THE BURDENS OF HISTORY...................................................................................................2 B. AFTER THE FALL: CHAOS AND NEW ASPIRATIONS................................................................4 II. THE RISE AND FALL OF THE ANA......................................................................... 7 III. ALBANIA: THE VIEW FROM TIRANA.................................................................. 11 IV. KOSOVO: INTERNAL DIVISIONS ......................................................................... 14 V. MACEDONIA: SHOULD WE STAY OR SHOULD WE GO? ............................... 17 VI. MONTENEGRO, SOUTHERN SERBIA AND GREECE....................................... 20 A. ALL QUIET ON THE WESTERN FRONT?................................................................................20 B. THE PRESEVO VALLEY IN SOUTHERN SERBIA....................................................................22 C. THE GREEK QUESTION........................................................................................................24 VII. EMIGRES, IDENTITY AND THE POWER OF DEMOGRAPHICS ................... 25 A. THE DIASPORA: POLITICS AND CRIME.................................................................................25 -

Dr Javed Iqbal Introduction IPRI Journal XI, No. 1 (Winter 2011): 77-95

An Overview of BritishIPRI JournalAdministrativeXI, no. Set-up 1 (Winter and Strategy 2011): 77-95 77 AN OVERVIEW OF BRITISH ADMINISTRATIVE SET-UP AND STRATEGY IN THE KHYBER 1849-1947 ∗ Dr Javed Iqbal Abstract British rule in the Indo-Pakistan Subcontinent, particularly its effective control and administration in the tribal belt along the Pak-Afghan border, is a fascinating story of administrative genius and pragmatism of some of the finest British officers of the time. The unruly land that could not be conquered or permanently subjugated by warriors and conquerors like Alexander, Changez Khan and Nadir Shah, these men from Europe controlled and administered with unmatched efficiency. An overview of the British administrative set-up and strategy in Khyber Agency during the years 1849-1947 would help in assessing British strengths and weaknesses and give greater insight into their political and military strategy. The study of the colonial system in the tribal belt would be helpful for administrators and policy makers in Pakistan in making governance of the tribal areas more efficient and effective particularly at a turbulent time like the present. Introduction ome facts of history have been so romanticized that it would be hard to know fact from fiction. British advent into the Indo-Pakistan S subcontinent and their north-western expansion right up to the hard and inhospitable hills on the Western Frontier of Pakistan is a story that would look unbelievable today if one were to imagine the wildness of the territory in those times. The most fascinating aspect of the British rule in the Indian Subcontinent is their dealing with the fierce and warlike tribesmen of the northwest frontier and keeping their land under their effective control till the very end of their rule in India. -

Deforestation in the Princely State of Dir on the North-West Frontier and the Imperial Strategy of British India

Central Asia Journal No. 86, Summer 2020 CONSERVATION OR IMPLICIT DESTRUCTION: DEFORESTATION IN THE PRINCELY STATE OF DIR ON THE NORTH-WEST FRONTIER AND THE IMPERIAL STRATEGY OF BRITISH INDIA Saeeda & Khalil ur Rehman Abstract The Czarist Empire during the nineteenth century emerged on the scene as a Eurasian colonial power challenging British supremacy, especially in Central Asia. The trans-continental Russian expansion and the ensuing influence were on the march as a result of the increase in the territory controlled by Imperial Russia. Inevitably, the Russian advances in the Caucasus and Central Asia were increasingly perceived by the British as a strategic threat to the interests of the British Indian Empire. These geo- political and geo-strategic developments enhanced the importance of Afghanistan in the British perception as a first line of defense against the advancing Russians and the threat of presumed invasion of British India. Moreover, a mix of these developments also had an impact on the British strategic perception that now viewed the defense of the North-West Frontier as a vital interest for the security of British India. The strategic imperative was to deter the Czarist Empire from having any direct contact with the conquered subjects, especially the North Indian Muslims. An operational expression of this policy gradually unfolded when the Princely State of Dir was loosely incorporated, but quite not settled, into the formal framework of the imperial structure of British India. The elements of this bilateral arrangement included the supply of arms and ammunition, subsidies and formal agreements regarding governance of the state. These agreements created enough time and space for the British to pursue colonial interests in Ph.D. -

“TELLING the STORY” Sources of Tension in Afghanistan & Pakistan: a Regional Perspective (2011-2016)

“TELLING THE STORY” Sources of Tension in Afghanistan & Pakistan: A Regional Perspective (2011-2016) Emma Hooper (ed.) This monograph has been produced with the financial assistance of the Norway Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not reflect the position of the Ministry. © 2016 CIDOB This monograph has been produced with the financial assistance of the Norway Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not reflect the position of the Ministry. CIDOB edicions Elisabets, 12 08001 Barcelona Tel.: 933 026 495 www.cidob.org [email protected] D.L.: B 17561 - 2016 Barcelona, September 2016 CONTENTS CONTRIBUTOR BIOGRAPHIES 5 FOREWORD 11 Tine Mørch Smith INTRODUCTION 13 Emma Hooper CHAPTER ONE: MAPPING THE SOURCES OF TENSION WITH REGIONAL DIMENSIONS 17 Sources of Tension in Afghanistan & Pakistan: A Regional Perspective .......... 19 Zahid Hussain Mapping the Sources of Tension and the Interests of Regional Powers in Afghanistan and Pakistan ............................................................................................. 35 Emma Hooper & Juan Garrigues CHAPTER TWO: KEY PHENOMENA: THE TALIBAN, REFUGEES , & THE BRAIN DRAIN, GOVERNANCE 57 THE TALIBAN Preamble: Third Party Roles and Insurgencies in South Asia ............................... 61 Moeed Yusuf The Pakistan Taliban Movement: An Appraisal ......................................................... 65 Michael Semple The Taliban Movement in Afghanistan ....................................................................... -

The Kingdom of Afghanistan: a Historical Sketch George Passman Tate

University of Nebraska Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Digitized Books 1-1-1911 The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch George Passman Tate Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tate, George Passman The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch, with an introductory note by Sir Henry Mortimer Durand. Bombay: "Times of India" Offices, 1911. 224 p., maps This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tate, G,P. The kfn&ean sf Af&mistan, DATE DUE I Mil 7 (7'8 DEDICATED, BY PERMISSION, HIS EXCELLENCY BARON HARDINGE OF PENSHURST. VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, .a- . (/. BY m HIS OBEDIENT, SERVANT THE AUTHOR. il.IEmtev 01 the Asiniic Society, Be?zg-nl, S?~rueyof I~din. dafhor of 'I Seisinqz : A Menzoir on the FJisio~y,Topo~rcrphj~, A7zliquiiies, (112d Peo$Ie of the Cozi?zt~y''; The F/.o?zlic7,.~ of Baluchisia'nn : Travels on ihe Border.? of Pe~szk n?zd Akhnnistnn " ; " ICalnf : A lMe??zoir on t7ze Cozl7~try and Fnrrzily of the Ahntadsai Khn7zs of Iinlnt" ; 4 ec. \ViTkI AN INrPR<dl>kJCTOl2Y NO'FE PRINTED BY BENNETT COLEMAN & Co., Xc. PUBLISHED AT THE " TIMES OF INDIA" OFFTCES, BOMBAY & C.1LCUTT-4, LONDON AGENCY : gg, SI-IOE LANE, E.C. -

Taliban and Anti-Taliban

Taliban and Anti-Taliban Taliban and Anti-Taliban By Farhat Taj Taliban and Anti-Taliban, by Farhat Taj This book first published 2011 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2011 by Farhat Taj All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-2960-9, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-2960-1 Dedicated to the People of FATA TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ...................................................................................... ix Preface........................................................................................................ xi A Note on Methodology...........................................................................xiii List of Abbreviations................................................................................. xv Chapter One................................................................................................. 1 Deconstructing Some Myths about FATA Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 33 Lashkars and Anti-Taliban Lashkars in Pakhtun Culture Chapter Three ........................................................................................... -

Afghan Women at the Crossroads: Agents of Peace—Or Its Victims?

AFGHAN WOMEN AT THE CROSSROADS: AGENTS OF PEACE—OR ITS VICTIMS? ORZALA ASHRAF NEMAT A CENTURY FOUNDATION REPORT The Century Foundation Headquarters: 41 East 70th Street, New York, New York 10021 D 212.535.4441 D.C.: 1333 H Street, N.W., 10th floor, Washington, D.C. 20005 D 202.387.0400 THE CENTURY FOUNDATION PROJECT ON AFGHANISTAN IN ITS REGIONAL AND MULTILATERAL DIMENSIONS This paper is one of a series commissioned by The Century Foundation as part of its project on Afghanistan in its regional and multilateral dimensions. This initiative is examining ways in which the international community may take greater collective responsibility for effectively assisting Afghanistan’s transition from a war-ridden failed state to a fragile but reasonably peaceful one. The program adds an internationalist and multilateral lens to the policy debate on Afghanistan both in the United States and globally, engaging the representatives of governments, international nongovernmental organizations, and the United Nations in the exploration of policy options toward Afghanistan and the other states in the region. At the center of the project is a task force of American and international figures who have had significant governmental, nongovernmental, or UN experience in the region, co-chaired by Lakhdar Brahimi and Thomas Pickering, respectively former UN special representative for Afghanistan and former U.S. undersecretary of state for political affairs. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors. Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the views of The Century Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before Congress.