Who Killed Buddy Holly ?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senior Musical Theater Recital Assisted by Ms

THE BELHAVEN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC Dr. Stephen W. Sachs, Chair presents Joy Kenyon Senior Musical Theater Recital assisted by Ms. Maggie McLinden, Accompanist Belhaven University Percussion Ensemble Women’s Chorus, Scott Foreman, Daniel Bravo James Kenyon, & Jessica Ziegelbauer Monday, April 13, 2015 • 7:30 p.m. Belhaven University Center for the Arts • Concert Hall There will be a reception after the program. Please come and greet the performers. Please refrain from the use of all flash and still photography during the concert Please turn off all cell phones and electronics. PROGRAM Just Leave Everything To Me from Hello Dolly Jerry Herman • b. 1931 100 Easy Ways To Lose a Man from Wonderful Town Leonard Bernstein • 1918 - 1990 Betty Comden • 1917 - 2006 Adolph Green • 1914 - 2002 Joy Kenyon, Soprano; Ms. Maggie McLinden, Accompanist The Man I Love from Lady, Be Good! George Gershwin • 1898 - 1937 Ira Gershwin • 1896 - 1983 Love is Here To Stay from The Goldwyn Follies Embraceable You from Girl Crazy Joy Kenyon, Soprano; Ms. Maggie McLinden, Accompanist; Scott Foreman, Bass Guitar; Daniel Bravo, Percussion Steam Heat (Music from The Pajama Game) Choreography by Mrs. Kellis McSparrin Oldenburg Dancer: Joy Kenyon He Lives in You (reprise) from The Lion King Mark Mancina • b. 1957 Jay Rifkin & Lebo M. • b. 1964 arr. Dr. Owen Rockwell Joy Kenyon, Soprano; Belhaven University Percussion Ensemble; Maddi Jolley, Brooke Kressin, Grace Anna Randall, Mariah Taylor, Elizabeth Walczak, Rachel Walczak, Evangeline Wilds, Julie Wolfe & Jessica Ziegelbauer INTERMISSION The Glamorous Life from A Little Night Music Stephen Sondheim • b. 1930 Sweet Liberty from Jane Eyre Paul Gordon • b. -

First Unitarian Universalist Society of Burlington, Vermont Order of Service September 13, 2020

First Unitarian Universalist Society of Burlington, Vermont Order of Service September 13, 2020 “Waters mingled, like our common humanity.” - Kayle Rice Prelude Polka Dots and Moonbeams Sam Whitesell Jimmy Van Heusen & Johnny Burke; arr. Sam Whitesell Welcome Judy Brook Chime Chalice “We kindle this chalice flame to remind ourselves of the light of truth, the warmth of community, and the fire of commitment.” Call to Worship “River Call” by Manish Mishra-Marzetti Rev. Patricia Hart Opening Song Come, Come, Whoever You Are Penny & Adele deRosset Meditation Spoken Words Joys & Sorrows Silence Reflection Offering Introduction Today’s offering will be shared with the Virtual Run/Walk for JUMP on September 26, the annual fundraising event for the Joint Urban Ministry Project. JUMP’s mission is to promote the physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being of people by providing spiritual care, direct assistance to meet basic needs, and advocacy. jumpvt.org Offertory Improvisation Sam Whitesell Offering Dedication “With gratitude, we dedicate these gifts in the service of our mission to inspire spiritual growth, care for each other and our community, seek truth, and act for justice.” Anthem Blue Boat Home FUUSB Choir Homily “Where Water Communion Came From” Water Communion Hymn #368 Now Let Us Sing Chalice Extinguishing “We extinguish this flame, but not the light of truth, the warmth of community, or the fire of commitment. These we carry in our hearts and share with the world until we are together again.” Benediction “All Rivers Run to the Sea” by Kayle Rice, adap. Erika Reif Postlude Waves Roll By Sam Whitesell TODAY’S WORSHIP CREATORS Developmental Senior Minister Rev. -

Jay Richardson Brushes Away Snow That's Drifted Around

When popular Beaumont deejay J.P. Richardson died on Feb. 3, 1959, with Buddy Holly and Ritchie Valens, he left behind more than ‘Chantilly Lace’ … he left a briefcase of songs never sung, a widow, a daughter and unborn son, and a vision of a brave new rock world By RON FRANSCELL Feb. 3, 2005 CLEAR LAKE, IOWA –Jay Richardson brushes away snow that’s drifted around the corpse-cold granite monument outside the Surf ballroom, the last place his dead father ever sang a song. Four words are uncovered: Their music lives on. But it’s just a headstone homily in this place where they say the music died. A sharp wind slices off the lake under a steel-gray sky. It’s the dead of winter and almost nothing looks alive here. The ballroom – a rock ‘n’ roll shrine that might not even exist today except for three tragic deaths – is locked up for the weekend. Skeletal trees reach their bony fingers toward a low and frozen quilt of clouds. A tattered flag’s halyard thunks against its cold, hollow pole like a broken church bell. And not a word is spoken. Richardson bows his head, as if to pray. This is a holy place to him. “I wish I hadn’t done that,” he says after a moment. Is he still haunted by the plane crash that killed a father he never knew? Can a memory be a memory if it’s only a dream? Why does it hurt him to touch this stone? “Cuz now my damn hand is cold,” Richardson says, smiling against the wind. -

Charles Mcpherson Leader Entry by Michael Fitzgerald

Charles McPherson Leader Entry by Michael Fitzgerald Generated on Sun, Oct 02, 2011 Date: November 20, 1964 Location: Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ Label: Prestige Charles McPherson (ldr), Charles McPherson (as), Carmell Jones (t), Barry Harris (p), Nelson Boyd (b), Albert 'Tootie' Heath (d) a. a-01 Hot House - 7:43 (Tadd Dameron) Prestige LP 12": PR 7359 — Bebop Revisited! b. a-02 Nostalgia - 5:24 (Theodore 'Fats' Navarro) Prestige LP 12": PR 7359 — Bebop Revisited! c. a-03 Passport [tune Y] - 6:55 (Charlie Parker) Prestige LP 12": PR 7359 — Bebop Revisited! d. b-01 Wail - 6:04 (Bud Powell) Prestige LP 12": PR 7359 — Bebop Revisited! e. b-02 Embraceable You - 7:39 (George Gershwin, Ira Gershwin) Prestige LP 12": PR 7359 — Bebop Revisited! f. b-03 Si Si - 5:50 (Charlie Parker) Prestige LP 12": PR 7359 — Bebop Revisited! g. If I Loved You - 6:17 (Richard Rodgers, Oscar Hammerstein II) All titles on: Original Jazz Classics CD: OJCCD 710-2 — Bebop Revisited! (1992) Carmell Jones (t) on a-d, f-g. Passport listed as "Variations On A Blues By Bird". This is the rarer of the two Parker compositions titled "Passport". Date: August 6, 1965 Location: Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ Label: Prestige Charles McPherson (ldr), Charles McPherson (as), Clifford Jordan (ts), Barry Harris (p), George Tucker (b), Alan Dawson (d) a. a-01 Eronel - 7:03 (Thelonious Monk, Sadik Hakim, Sahib Shihab) b. a-02 In A Sentimental Mood - 7:57 (Duke Ellington, Manny Kurtz, Irving Mills) c. a-03 Chasin' The Bird - 7:08 (Charlie Parker) d. -

Title Composer Lyricist Arranger Cover Artist Publisher Date Notes Sabbath Chimes (Reverie) F

Title Composer Lyricist Arranger Cover artist Publisher Date Notes Sabbath Chimes (Reverie) F. Henri Klickmann Harold Rossiter Music Co. 1913 Sack Waltz, The John A. Metcalf Starmer Eclipse Pub. Co. [1924] Sadie O'Brady Billy Lindemann Billy Lindemann Broadway Music Corp. 1924 Sadie, The Princess of Tenement Row Frederick V. Bowers Chas. Horwitz J.B. Eddy Jos. W. Stern & Co. 1903 Sail Along, Silv'ry Moon Percy Wenrich Harry Tobias Joy Music Inc 1942 Sail on to Ceylon Herman Paley Edward Madden Starmer Jerome R. Remick & Co. 1916 Sailin' Away on the Henry Clay Egbert Van Alstyne Gus Kahn Starmer Jerome H. Remick & Co. 1917 Sailin' Away on the Henry Clay Egbert Van Alstyne Gus Kahn Starmer Jerome H. Remick & Co. 1917 Sailing Down the Chesapeake Bay George Botsford Jean C. Havez Starmer Jerome H. Remick & Co. 1913 Sailing Home Walter G. Samuels Walter G. Samuels IM Merman Words and Music Inc. 1937 Saint Louis Blues W.C. Handy W.C. Handy NA Tivick Handy Bros. Music Co. Inc. 1914 Includes ukulele arrangement Saint Louis Blues W.C. Handy W.C. Handy Barbelle Handy Bros. Music Co. Inc. 1942 Sakes Alive (March and Two-Step) Stephen Howard G.L. Lansing M. Witmark & Sons 1903 Banjo solo Sally in our Alley Henry Carey Henry Carey Starmer Armstronf Music Publishing Co. 1902 Sally Lou Hugo Frey Hugo Frey Robbins-Engel Inc. 1924 De Sylva Brown and Henderson Sally of My Dreams William Kernell William Kernell Joseph M. Weiss Inc. 1928 Sally Won't You Come Back? Dave Stamper Gene Buck Harms Inc. -

12.4 Radio Days Song List

BIG BAND SONG LIST Laughter to raise a nation’s spirits. Music to stir a nation’s soul. Lorie Carpenter-Niska • Sheridan Zuther Kurt Niska • Michael Swedberg • Terrence Niska A Five By Design Production I’ve Got A Gal In Kalamazoo ..........................Mack Gordon & Harry Warren Big Noise From Winnetka .Bob Haggart, Ray Bauduc, Gil Rodin & Bob Crosby I’ll Never Smile Again ..............................................................Ruth Lowe Three Little Fishies .............................................................. Saxie Dowell Mairzy Doats .............................Milton Drake, Al Hoffman & Jerry Livingston Personality ........................................... Jimmy Van Heusen & Johnny Burke Managua Nicaragua ....................................... Albert Gamse & Irving Fields Opus One...................................................................................Sy Oliver Moonlight In Vermont............................... John Blackburn & Karl Seussdorf Juke Box Saturday Night ..................................Al Stillman & Paul McGrane Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy .................................. Don Raye & Hughie Prince INTERMISSION A-Tisket, A-Tasket ...................................... Van Alexander & Ella Fitzgerald Roodle Dee Doo ......................................Jimmy McHugh & Harold Adamson Halo Shampoo .......................................................................... Joe Rines The Trolley Song............................................... Ralph Blane & Hugh Martin Let’s Remember Pearl Harbor -

Stars Over Clear Lake D Loretta Ellsworth

Stars Over Clear Lake d Loretta Ellsworth Thomas Dunne Books St. Martin's Press New York 053-66526_ch00_5P.indd iii 2/20/17 6:56 AM This is a work of fi ction. All of the characters, organ izations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fi ctitiously. thomas dunne books. An imprint of St. Martin’s Press. stars over clear lake. Copyright © 2017 by Loretta Ellsworth. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of Amer i ca. For information, address St. Martin’s Press, 175 Fifth Ave nue, New York, N.Y. 10010. www . thomasdunnebooks . com www . stmartins . com Title-page photo courtesy of freeimages.com The Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data is available upon request. ISBN 978-1-250-09703-3 (hardcover) ISBN 978-1-250-09704-0 (e-book) Our books may be purchased in bulk for promotional, educational, or business use. Please contact your local bookseller or the Macmillan Corporate and Premium Sales Department at 1-800-221-7945, extension 5442, or by e-mail at MacmillanSpecialMarkets@macmillan. com. First Edition: May 2017 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 053-66526_ch00_5P.indd iv 2/20/17 6:56 AM One d 2007 haven’t been inside this place in fi fty years,” I say softly as I pause in Ifront of the sand-colored brick building. The outside of the Surf Ballroom hasn’t changed from when it opened in 1948, its rounded roof making it look like a roller derby from the outside. -

Rock Hall and Surf Ballroom Announce 50 Winters Later Tribute

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Laurie Lietz, Surf Ballroom & Museum, (641) 357-6151, [email protected] Margaret Thresher, Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum, (216) 515-1215, [email protected] The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Surf Ballroom & Museum Announce Concert Lineup for 50 Winters Later Tribute Weeklong series of events to be announced soon CLEAR LAKE (December 11, 2008) – The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum, along with the Surf Ballroom & Museum, will honor the 50 th anniversary of the Winter Dance Party with a weeklong series of events beginning on Wednesday, January 28 that will culminate in a tribute concert at the Surf Ballroom where Buddy Holly , J.P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson and Ritchie Valens played their final concert. The tribute will feature an all-star lineup including Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductee Graham Nash, Tommy Allsup, the Crickets, Bobby Vee, Los Lobos, Los Lonely Boys, Joe Ely and Wanda Jackson . SIRIUS XM Radio host Bruce “Cousin Brucie” Morrow will be the emcee and Sandra Boynton and Sir Tim Rice will participate in the tribute portion of the concert. Additional artists will be announced in the coming weeks. The 50 Winters Later tribute concert will take place the evening of Monday, February 2 at the Surf Ballroom in Clear Lake, Iowa. General admission tickets will go on sale this Monday, December 15 for $85. They can be purchased at www.50winterslater.com or by calling the Surf Ballroom’s box office at (641) 357-6151. A limited number of $1,000 VIP packages are available. -

His Debut Album the Way I'm Made

SPECIAL EDITION Pages 12 - 26 Volume 71 No. 6June 12, 2000 BLINK182 goes triple platinum - Page 2 $3.00 ($2.80 plus .20 GST) Publication Mail Registration No. 08141 his debut albumThe Way I'm Made Includes "Horseshoes" . www adamgregory com 2 - RPM - Monday June 12, 2000 tribute Unforgettable. Verve/Universal release newDenzal Sinclaire album As Densil Pinnock, he released two previous Hot on the heels of the enormous international vocalist -pianist," notes Ken Druker, label manager albums, I Waited For You and Mona Lisa, appeared success of BC native Diana Krall, Verve Records is for Verve. in numerous stage productions and starred in his Mill111111111111111111111 offering the new release, titled I Found Love, from Sinclaire is a graduate of McGill University, own Bravo! television special. He also received the Vancouver native Denzal Sinclaire, formerly known obtaining a Bachelor of Music Degree in jazz Jazz Report male jazz vocalist award three years as Densil Pinnock. performance. Having performed at various festivals running (1994-97). The album, recorded in Vancouver, is an all - throughout Europe and North America, Sinclaire has I Found Love was released to retail on May Canadian production, featuring three original tracks performed with the likes of Jimmy Heath, Richard 23. Sinclair is slated to perform at the Vancouver written by Sinclaire and longtime collaborator Bill Wyans and Campbell Ryga. In April of this year he East Cultural Centre (June 27) and the Montreal Coon. The songs highlight Sinclaire's strong tenor portrayed Nat King Cole in the acclaimed musical International Jazz Festival (July 6). vocals and Coon's arrangements. -

"A" - You're Adorable (The Alphabet Song) 1948 Buddy Kaye Fred Wise Sidney Lippman 1 Piano Solo | Twelfth 12Th Street Rag 1914 Euday L

Box Title Year Lyricist if known Composer if known Creator3 Notes # "A" - You're Adorable (The Alphabet Song) 1948 Buddy Kaye Fred Wise Sidney Lippman 1 piano solo | Twelfth 12th Street Rag 1914 Euday L. Bowman Street Rag 1 3rd Man Theme, The (The Harry Lime piano solo | The Theme) 1949 Anton Karas Third Man 1 A, E, I, O, U: The Dance Step Language Song 1937 Louis Vecchio 1 Aba Daba Honeymoon, The 1914 Arthur Fields Walter Donovan 1 Abide With Me 1901 John Wiegand 1 Abilene 1963 John D. Loudermilk Lester Brown 1 About a Quarter to Nine 1935 Al Dubin Harry Warren 1 About Face 1948 Sam Lerner Gerald Marks 1 Abraham 1931 Bob MacGimsey 1 Abraham 1942 Irving Berlin 1 Abraham, Martin and John 1968 Dick Holler 1 Absence Makes the Heart Grow Fonder (For Somebody Else) 1929 Lewis Harry Warren Young 1 Absent 1927 John W. Metcalf 1 Acabaste! (Bolero-Son) 1944 Al Stewart Anselmo Sacasas Castro Valencia Jose Pafumy 1 Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive 1944 Johnny Mercer Harold Arlen 1 Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive 1944 Johnny Mercer Harold Arlen 1 Accidents Will Happen 1950 Johnny Burke James Van Huesen 1 According to the Moonlight 1935 Jack Yellen Joseph Meyer Herb Magidson 1 Ace In the Hole, The 1909 James Dempsey George Mitchell 1 Acquaint Now Thyself With Him 1960 Michael Head 1 Acres of Diamonds 1959 Arthur Smith 1 Across the Alley From the Alamo 1947 Joe Greene 1 Across the Blue Aegean Sea 1935 Anna Moody Gena Branscombe 1 Across the Bridge of Dreams 1927 Gus Kahn Joe Burke 1 Across the Wide Missouri (A-Roll A-Roll A-Ree) 1951 Ervin Drake Jimmy Shirl 1 Adele 1913 Paul Herve Jean Briquet Edward Paulton Adolph Philipp 1 Adeste Fideles (Portuguese Hymn) 1901 Jas. -

IMAGINATION-Jimmy Van Heusen/Johnny Burke 4/4

IMAGINATION-Jimmy Van Heusen/Johnny Burke 4/4 Do you re-member Don Quixote? Or the Bulping-ton of Blup? The things they thought of can't compare with the things my mind makes up. Imagin-ation is funny, it makes a cloudy day sunny It makes a bee think of honey, just as I think of you Imagin-ation is crazy, your whole per-spective gets hazy Starts you asking a daisy, what to do, what to do Have you ever felt a gentle touch, and then a kiss, and then and then Find it's only your im-agin -ation a-gain? Oh, well, p.2. Imagination Imagin-ation is silly, you go a-round willy nilly For ex-ample I go a-round wanting you And yet, I can't im-agine that you want me too Yet I can't im-agine that you want me too IMAGINATION-Jimmy Van Heusen/Johnny Burke 4/4 E7 Am D9 Bm7 Bdim G6 Do you re-member Don Quixote? Or the Bulping-ton of Blup? E7 Am D9 Am7b5 G6 C#dim D7 D7b9 G7 G7#5 The things they thought of can't compare with the things my mind makes up. C C#dim Dm7 D#dim C Em7b5 A7b9 A7 Imagin-ation is funny, it makes a cloudy day sunny Dm A7#5 Dm7 G9#5 Em7 A7b9 Dm7 G7 It makes a bee think of honey, just as I think of you G7#5 C C#dim Dm7 D#dim C Em7b5 A7b9 A7 Imagin-ation is crazy, your whole per-spective gets hazy Dm A7#5 Dm7 G9#5 C CMA7 Gm7 C9 F#7b5 Starts you asking a daisy, what to do, what to do FMA7 F#m7b5 B7 Em7 A7 Bbdim Have you ever felt a gentle touch, and then a kiss, and then and then Bm7 Em7 Am7 D7 Dm7 G7#5 Find it's only your im-agin-ation a-gain? Oh, well, C C#dim Dm7 D#dim C Em7b5 A7b9 A7 Imagin-ation is silly, you go a-round willy nilly Dm A7#5 Dm7 Bm7b5 E7#5 E7b5 A7b9 For ex-ample I go a-round wanting you A7#5 A7 Dm7 G7sus G7b9 C6 Em7b5 And yet, I can't im-agine that you want me too A7#5 A7 Dm7 G7sus G7b9 C6 Bb6 B6 C6 Yet I can't im-agine that you want me too . -

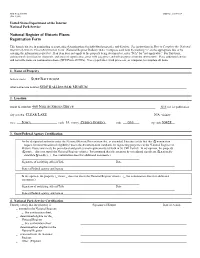

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" on the appropriate line or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name SURF BALLROOM other names/site number SURF BALLROOM & MUSEUM 2. Location street & number 460 NORTH SHORE DRIVE N/A not for publication city or town CLEAR LAKE N/A vicinity state IOWA code IA county CERRO GORDO code 033 zip code 50428 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this (X nomination _ request for determination of eligibility) meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property (X meets _ does not meet) the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant (X nationally _ statewide X locally).