The Sinking of the Troop Transport, H.M.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Chili Feed and Heritage Fair

WWI Razzle-Dazzle Odd Fellows Cabins Tricked German Subs Get Needed TLC After heavy losses of ships in the Historicorps in cooperation with North Atlantic during World War DCHS complete critical first phases I, British planners razzle-dazzled of stabilization work needed to save German U-boat commanders. the four cabins. See Page 2 See Page 3 The Homesteader Deschutes County Historical Society Newsletter – November 2017 ANNUAL CHILI FEED AND HERITAGE FAIR It’s time for the Annual Chili Feed and Heritage Fair, last winter, who doesn’t want to win one of those? November 10-11 at the Deschutes Historical Museum. Last year we launched a small genealogy research Millie’s Chili with Rastovich Farms Barley Beef can’t table—this year, with support from the Deschutes be beat—a family tradition that has helped support the Cultural Coalition, we are expanding our genealogy museum for over thirty years. A special time to visit session to a full two-day Heritage Fair designed to jump the museum and catch up with other members and start your genealogy research. volunteers. The Bake Sale features tasty treats from our members, homemade jams and jellies, and things you Our featured presenter is Lisa McCullough, a genetic can’t find anywhere else. The Raffle is lining up great genealogy researcher and lecturer. Commercials local staycations, nights on the town, the ever fought promise ancestral discoveries through simple DNA tests—swab your cheek and send it off, but what are over table at History Pub and—a snow blower! After -- continued on page 4 The Homesteader: Volume 43; No. -

United States Navy and World War I: 1914–1922

Cover: During World War I, convoys carried almost two million men to Europe. In this 1920 oil painting “A Fast Convoy” by Burnell Poole, the destroyer USS Allen (DD-66) is shown escorting USS Leviathan (SP-1326). Throughout the course of the war, Leviathan transported more than 98,000 troops. Naval History and Heritage Command 1 United States Navy and World War I: 1914–1922 Frank A. Blazich Jr., PhD Naval History and Heritage Command Introduction This document is intended to provide readers with a chronological progression of the activities of the United States Navy and its involvement with World War I as an outside observer, active participant, and victor engaged in the war’s lingering effects in the postwar period. The document is not a comprehensive timeline of every action, policy decision, or ship movement. What is provided is a glimpse into how the 20th century’s first global conflict influenced the Navy and its evolution throughout the conflict and the immediate aftermath. The source base is predominately composed of the published records of the Navy and the primary materials gathered under the supervision of Captain Dudley Knox in the Historical Section in the Office of Naval Records and Library. A thorough chronology remains to be written on the Navy’s actions in regard to World War I. The nationality of all vessels, unless otherwise listed, is the United States. All errors and omissions are solely those of the author. Table of Contents 1914..................................................................................................................................................1 -

September 2017

The Saltire September 2017 Welcome! . to this, the September edition of The Saltire - the newsletter of the Saint Andrew Society of Western Australia. This is the quiet time of year for the Society, with many of our members taking off to the northern hemisphere, visiting friends and family in Scotland and elsewhere, or just ‘visiting the sites’. It's for the latter reason that I find myself sitting writing this in a hotel in San Franciso at 4:30am, wondering if my body-clock is ever going to be the same again! (We left Perth at 6:15am on a Monday morning and were in our hotel in SF by lunch time the same day – how does that work?!) There being less Society business to write about, I intend to include some material of a more general nature in this edition, which I hope you might find interesting. In this edition: • Society business since the last Saltire. • Upcoming events. • ‘Tommy’s Honour’. • Patrick Grant – the portrait of a rebel. • The ‘Tuscania’ – an Islay ship-wreck. Page 1 of 19 The Saltire September 2017 Society Business Weekend Away Since the Chieftain’s Ceilidh in May, there has only been one event, which was the ‘Weekend Away’. Last year’s event was held in the somewhat tired surroundings of the old El Caballo Blanco resort in the hills east of Perth. This year, we travelled further afield, to Quindanning, a 'one horse town' (actually, a 'three house town'!) a little to the south of the enormous gold mining operation around Boddington. While it’s a bit of a hike down to Quindanning, the effort was worth it. -

An Analysis of the United States and United Kingdom Smallpox Epidemics (1901–5) – the Special Relationship That Tested Public Health Strategies for Disease Control

Med. Hist. (2020), vol. 64(1), pp. 1–31. c The Author 2019. Published by Cambridge University Press 2019 This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:10.1017/mdh.2019.74 An Analysis of the United States and United Kingdom Smallpox Epidemics (1901–5) – The Special Relationship that Tested Public Health Strategies for Disease Control BERNARD BRABIN 1,2,3 * 1Clinical Division, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, Pembroke Place, Liverpool, L3 5QA, UK 2Institute of Infection and Global Health, University of Liverpool, UK 3Global Child Health Group, Academic Medical Centre, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands Abstract: At the end of the nineteenth century, the northern port of Liverpool had become the second largest in the United Kingdom. Fast transatlantic steamers to Boston and other American ports exploited this route, increasing the risk of maritime disease epidemics. The 1901–3 epidemic in Liverpool was the last serious smallpox outbreak in Liverpool and was probably seeded from these maritime contacts, which introduced a milder form of the disease that was more difficult to trace because of its long incubation period and occurrence of undiagnosed cases. The characteristics of these epidemics in Boston and Liverpool are described and compared with outbreaks in New York, Glasgow and London between 1900 and 1903. Public health control strategies, notably medical inspection, quarantine and vaccination, differed between the two countries and in both settings were inconsistently applied, often for commercial reasons or due to public unpopularity. -

Cairy, Scott OH732

Thomas Doherty Papers and Photographs Transcript of an Oral History Interview with SCOTT A. CAIRY Officer, National Guard, 32 nd Infantry Division, WWI; Officer, Wisconsin State Guard, World War II. 1979 Wisconsin Veterans Museum Madison, Wisconsin OH 732 1 OH 732 Cairy, Scott A., (1889-1986). Oral History Interview, 1979. Master Copy: 1 sound cassette (ca. 50 min.), analog, 1 7/8 ips, mono. Safety Master Copy: 1 sound cassette (ca. 50 min.), analog, 1 7/8 ips, mono. Transcript: 0.1 linear ft. (1 folder). Military Papers: 0.1 linear ft. (1 folder). Abstract: Scott A. Cairy, an Andrew, Iowa native, discusses his career with the 32 nd Infantry Division and Wisconsin National Guard, including service in France in World War I and stateside during World War II. Cairy talks about organizing a National Guard unit for Platteville (Wisconsin) after the declaration of war in 1917: calling the adjutant general, enlisting over two hundred men, being commissioned as a 1 st lieutenant, mobilizing at Camp Douglas (Wisconsin), and training at Camp MacArthur (Texas), where the 32 nd Division was organized. He tells of getting orders for his regiment to sail overseas on the SS Tuscania , having his orders changed to the SS Orduna instead, seeing the destruction at Halifax Harbor the day after the explosive collision of two ships, riding to Liverpool in a convoy, and hearing the Tuscania had been sunk. Cairy details the tough training at Camp Coëtquidan (Brittany, France) before leaving for the Front. He speaks of his first battle in Alsace Lorraine, commanding a group of machine guns, a forced march to Chateau-Thierry, and being gassed directly after their arrival. -

Overnight When the War Came to Islay

OVERNIGHT WHEN THE WAR CAME TO ISLAY 161861 Overnight.indd 1 23/04/2018 14:34 Tuscania flag and graves 161861 Overnight.indd 2 23/04/2018 14:34 OVERNIGHT WHEN THE WAR CAME TO ISLAY 1 QUEEN OF THE HEBRIDES 2 CALM BEFORE THE STORM 3 AT SEA 4 A VERY DISTRESSFUL DAY FOR EVERYBODY 5 THE WORST CONVOY DISASTER OF THE WAR 6 LOSS MADE VISIBLE 161861 Overnight.indd 1 23/04/2018 14:34 161861 Overnight.indd 2 23/04/2018 14:34 Extract from James MacTaggart’s diary showing the impact of the Otranto disaster Extract from James MacTaggart’s diary showing the impact of the Otranto disaster 161861 Overnight.indd 3 23/04/2018 14:34 QUEEN OF THE HEBRIDES Islay is known as the Queen of the Hebrides - perhaps due to its former political prominence in the 12th Century when the Lords of the Isles resided there, or maybe simply for its beauty and its softer, greener appearance than its northern counterparts Mull and Skye. Certainly on a sunny summer’s day, sheltered from the wind by a whitewashed croft wall with the sparkling sea beyond, one could be convinced it was an Aegean island or a patch of heaven. 4 OVERNIGHT 161861 Overnight.indd 4 23/04/2018 14:34 The southernmost of the Inner Hebrides islands, Islay is the fifth largest Scottish island with a landmass of 239 square miles and a coastline of 130 miles. It is about 25 miles long and 15 miles wide at its longest and broadest points. -

Armistice Day: Remember the Centennial

ARMISTICE DAY: REMEMBER THE CENTENNIAL PLUS Explore North Texas’ WWI Heritage I Historic Victory Parade Photos WWI Veteran Headstones ISSN 0890-7595 Vol. 56, No. III thc.texas.gov [email protected] TEXAS HISTORICAL COMMISSION John L. Nau, III Chair John W. Crain Vice Chair Gilbert E. “Pete” Peterson Secretary Earl Broussard, Jr. David A. Gravelle James “Jim” Bruseth Chief Justice Wallace B. Jefferson (ret.) Monica P. Burdette Laurie E. Limbacher Garrett Kieran Donnelly Catherine McKnight Renee Rupa Dutia Tom Perini Lilia Marisa Garcia Daisy Sloan White Mark Wolfe Executive Director Medallion STAFF Chris Florance Division Director Andy Rhodes Managing Editor Judy Jensen Sr. Graphic Design Coordinator thc.texas.gov Real places telling the real stories of Texas texastimetravel.com The Texas Heritage Trails Program’s travel resource texashistoricsites.com The THC’s 22 state historic properties thcfriends.org Friends of the Texas Historical Commission Our Mission To protect and preserve the state’s historic and prehistoric resources for the use, education, enjoyment, and economic benefit of present and future generations. The Medallion is published quarterly by the Texas Historical Commission. Address correspondence to: Managing Editor, The Medallion, P.O. Box 12276, Austin, TX 78711-2276. Portions of the newsletter that are not copyrighted or reprinted from other sources may be reprinted with permission. Contributions for the support of this publication are gratefully accepted. For information about alternate formats of this publication, contact the THC at 512-463-6255. The Medallion is financed in part by a grant from the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. -

Texas and the Great War Travel Guide

Credit: Wikimedia Commons In the 1916 presidential election, Woodrow Wilson In many ways, World War I is a forgotten war, campaigned on “He Kept Us Out of War.” While the Great overshadowed by the major conflicts that preceded and War raged abroad, this slogan reassured Americans that followed it. But its impact was profound. It normalized their boys would not be shipped off to the killing fields of airplanes in skies and made death by machine gun, poison Europe. But on April 6, 1917, just a month after Wilson’s gas, or artillery the new normal for soldiers. It catalyzed second inauguration, the U.S. found itself joining the fight reform movements, invigorated marginalized groups, that in just three years had brought powerful empires to and strained America’s commitment to the protection of their knees. civil liberties within its own borders. It did all this while turning the U.S. into a creditor nation for the first time The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria- in its history, and granting it a new—albeit temporary— Hungary by Serbian separatists was the spark that ignited importance on the international stage. The U.S., and a bold, the war. It was fueled by an ongoing arms race, rising modern new world, had finally arrived. nationalism, and decades of resentment and competition between powerful European nations. Dozens of nations and Texas was at the forefront of much of this change. colonial territories eventually aligned themselves behind Thousands of its residents, along with new migrants from one of two opposing power blocs: the Triple Entente (or the rest of the U.S. -

Report and Recommendations of the Scottish

REFLECTIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE SCOTTISH COMMEMORATIONS PANEL WW100 SCOTLAND REPORT 2019 Contents Foreword Page 5 Summary of Recommendations Page 6 Chapter One The Panel and its Purpose Page 7 Chapter Two The Commemorative Programme Page 9 Chapter Three Partnerships Page 11 Chapter Four The use of Social Media Page 13 Chapter Five WHAT DO WE LEARN FROM ALL TH1S? Page 14 Annex A Panel Purpose and Objectives Page 16 Annex B The Scottish Commemorations Panel (SCP) Page 17 Annex C The Scottish Commemorative Programme Page 19 Annex D Historic Document booklets Page 22 3 Foreword Since being appointed to serve in early 2013 the Scottish Commemorations Panel has, throughout the commemorative period, been asking of themselves and of others the telling strapline question of “WHAT DO WE LEARN FROM ALL TH1S?” As the WW100 Scotland commemorations draw to a close – with the presentation of Certificates to Primary and Secondary schools the length and breadth of Scotland, and the laying up of a WW100 Scotland Time Capsule to be opened on 4 August 2114 and the concluding WW100 Scotland Exhibition and Art Installation in the Scottish Parliament – our thoughts have inevitably and inexorably turned to asking the question “WHAT DO WE LEARN FROM ALL TH1S?” We trust that this report, comprising 44 meetings and the organisation of 17 major events here in Scotland and overseas, alongside the supervision and encouragement of countless others across Scotland, will prove of encouragement and benefit to our successors in forthcoming commemorative events and years. Perhaps 3 main themes have emerged and sustained us in our work on behalf of those ‘who for our tomorrow gave their today’. -

Eastford Historical Society Off To

EASTFORD HISTORICAL SOCIETY QUARTERLY Vol. 42 No. 4 December 2018 OFF TO WAR United States Enters World War 1 By Toni Doubleday “He kept us out of war” was President Wilson’s popular World War I Stories of Notable Interest Involving Eastford campaign slogan in the 1916 election and largely the senti- Soldiers and Citizens ment of most American citizens, i.e., to stay out of what many thought of as a European conflict. With the sinking Charles Barrington registered in Eastford on June 4, 1917 of the Lusitania and 2 days thereafter the sinking of the as required by Congress. Thereafter both Charles and his Housatonic, both with many American lives lost, pressure friend Edwin Lewis left Connecticut heading west on mo- was mounting for our country to reconsider its stance on torcycles to visit Charles’ sister in California. Another staying out of World War I. An apology from Germany account of their travels tells us that both boys had an op- for the sinking of the Lusitania and a change in that coun- portunity to work in the state of Washington. Before leav- try’s unrestricted policy on attacking ships, further delayed ing, Charles failed to notify the local draft board of his making a decision to join forces with the United Kingdom. new address. On July 28th he Finally, after remaining neutral for three years, the United was ordered by the local exemp- States, provoked by Germany’s resumption of unrestricted tion board to report in Putnam U boat warfare on sea going vessels, officially entered the for a physical exam. -

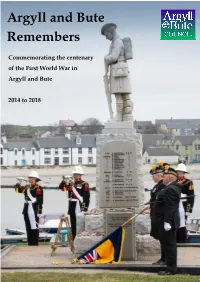

Argyll and Bute Remembers

Argyll and Bute Remembers Commemorating the centenary of the First World War in Argyll and Bute 2014 to 2018 1 Foreword—Provost of Argyll and Introduction—HM Lord- Bute, Councillor Len Scoullar Lieutenant of Argyll and Bute, Patrick Stewart One hundred years ago, when war broke out in It has been an honour and a privilege to chair the 1914, the people of Argyll and Bute were World War 1 Commemoration Steering Group steadfast and determined in their response— since its inception in 2013, created with the aim whether it was sending husbands, fathers and of co-ordinating World War 1 commemoration sons to serve the country on those dark and activities across Argyll and Bute during the four- distant battlefields, ensuring the vital agricultural year centenary period. and other domestic contributions continued, or Over this four-year period, the group has worked responding to tragedies which brought the war in partnership with Argyll and Bute Council and a to Argyll’s very shores. myriad of local people and groups. During the four-year centenary period, our The commemoration activities in which the people have been equally determined to ensure group has been involved have included very per- that Argyll and Bute remembers— not only for sonal family tributes—such as the four Victoria this special time of commemoration but in the Cross commemorative paving stone ceremonies, future, too. where family members gathered to reflect on Enclosed in this booklet you will find just some the bravery of their forefathers. They have been examples and stories of how Argyll and Bute educational—look at the exhibitions outlining remembers—from key annual events across the Argyll’s contributions to the war effort, and the area to school projects, and much more besides. -

![The American Legion Magazine [Volume 23, No. 3 (September 1937)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4905/the-american-legion-magazine-volume-23-no-3-september-1937-10164905.webp)

The American Legion Magazine [Volume 23, No. 3 (September 1937)]

SEPTEMBER- 1937 Nineteenth National Convention • New York September 20-23 Copyright 1937, Liggett & Myers Tobacco Co. — We ll B e SeeingYou By D I A City of New York is proud New York is itself a city of superla- United States and that here Washing- THEand happy to welcome The tives. We New Yorkers who have at- ton took the oath of office for the American Legion on the occa- tended national conventions of the Presidency under the Constitution sion of its Nineteenth Annual Legion are certain that our fellow whose century and a half of existence National Convention. We invite all townsmen are going to learn a good we are celebrating this year. Some Legionnaires, Forty and Eighters, deal about the Legion that they can- of the places you should visit will be Auxiliares and Sons of the Legion to not possibly know now. That march fisted in the booklet you will receive come along and partake of Father up Fifth Avenue will itself make when you register. Along with the Knickerbocker's hospitality. We sure history. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Mu- will try to give you a good time. seum of Natural History, Aquarium, The cosmopolitan character of New \\ 7"HILE you are with us you will Parks, our City Hall, and other points " York City has been stressed for a * come under the scrutiny of men of interest acclaimed by world travel- century or more, and it is our boast and women whose opinions, expressed ers, I would like to extend to you a that nobody that comes to us need be in syndicated newspaper articles, in special invitation to visit the Museum lonesome.