Latin America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Jewish Yearbook

JEWISH STATISTICS 277 JEWISH STATISTICS The statistics of Jews in the world rest largely upon estimates. In Russia, Austria-Hungary, Germany, and a few other countries, official figures are obtainable. In the main, however, the num- bers given are based upon estimates repeated and added to by one statistical authority after another. For the statistics given below various authorities have been consulted, among them the " Statesman's Year Book" for 1910, the English " Jewish Year Book " for 5670-71, " The Jewish Ency- clopedia," Jildische Statistik, and the Alliance Israelite Uni- verselle reports. THE UNITED STATES ESTIMATES As the census of the United States has, in accordance with the spirit of American institutions, taken no heed of the religious convictions of American citizens, whether native-born or natural- ized, all statements concerning the number of Jews living in this country are based upon estimates. The Jewish population was estimated— In 1818 by Mordecai M. Noah at 3,000 In 1824 by Solomon Etting at 6,000 In 1826 by Isaac C. Harby at 6,000 In 1840 by the American Almanac at 15,000 In 1848 by M. A. Berk at 50,000 In 1880 by Wm. B. Hackenburg at 230,257 In 1888 by Isaac Markens at 400,000 In 1897 by David Sulzberger at 937,800 In 1905 by "The Jewish Encyclopedia" at 1,508,435 In 1907 by " The American Jewish Year Book " at 1,777,185 In 1910 by " The American Je\rish Year Book" at 2,044,762 DISTRIBUTION The following table by States presents two sets of estimates. -

Vanity Fair Songlist

VANITY FAIR SONGLIST Popular Jazz Almost Like Being In Love Natalie Cole The Boy From New York City Manhattan Transfer Come Fly With Me Michael Buble’ How Sweet It Is Michael Buble’ It Had To Be You Harry Connick, Jr. La Vie En Rose Edith Piaf L-O-V-E Natalie Cole The More I See You Michael Buble’ Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien Edith Piaf Paper Moon Natalie Cole Route 66 Natalie Cole Sway The Pussycat Dolls Jazz Standards, Swing Ain’t That A Kick In The Head Dean Martin Basin Street Blues Louis Armstrong Fever Peggy Lee Fly Me To The Moon Frank Sinatra In The Mood Glen Miller Mack The Knife Bobby Darin Moonlight In Vermont Frank Sinatra New York New York Frank Sinatra Satin Doll Duke Ellington The Way You Look Tonight Frank Sinatra Take The “A” Train Duke Ellington Latin, Latin Jazz, Latin Pop, Latin Rock, World Music The Girl From Ipanema Astrud Gilberto Hips Don’t Lie Shakira/Wyclef Jean La Bamba Los Lobos The Miami Sound Machine Medley Miami Sound Machine Conga/Rhythm Is Gonna Get You/Get On Your Feet Mi Tierra Gloria Estefan Perfidia Linda Ronstadt Suavecito Malo Oldies A Hard Day’s Night The Beatles A Little Less Conversation Elvis Presley All Shook Up Elvis Presley At The Hop Danny & The Juniors Bandstand Boogie Barry Manilow Bo Diddley Bo Diddley Book Of Love The Monotones Brown-Eyed Girl Van Morrison Build Me Up Buttercup The Foundations Can’t Help Falling In Love Elvis Can’t Take My Eyes Off Of You Frankie Valli Chantilly Lace The Big Bopper Charlie Brown The Coasters Devil With A Blue Dress Mitch Ryder Don’t Be Cruel Elvis Presley Fun, Fun, Fun The Beach Boys Good Golly Miss Molly Little Richard Great Balls Of Fire Jerry Lee Lewis Happy Together The Turtles Hound Dog Elvis Presley I Saw Her Standing There The Beatles I Say A Little Prayer For You Dionne Warwick It’s My Party Lesley Gore It’s Not Unusual Tom Jones Jailhouse Rock Elvis Presley Johnny B. -

Jewish Out-Marriage: Mexico and Venezuela

International Roundtable on Intermarriage – Brandeis University, December 18, 2003 Jewish Out-Marriage: Mexico and Venezuela Sergio DellaPergola The Avraham Harman Institute of Contemporary Jewry The Hebrew University of Jerusalem and The Jewish People Policy Planning Institute Background This chapter deals with recent Jewish family developments in some Spanish speaking countries in the central areas of the American continent. While not the largest in size, during the second half of the 20th century these communities have represented remarkably successful examples of richly structured, attractive and resilient Jewish communities. The Latin American model of Jewish community organization developed in the context of relatively poor and highly polarized societies where social-class stratification often overlapped with differentials between the descendants of native civilizations and the descendants of settlers from Western European countries—primarily Spain. Throughout most of the 20th century the general political context of these societies was characterized by considerable concentrations of central presidential power within a state structure often formally organized in a federal format. Mexico and Venezuela featured a comparatively more stable political environment than other countries in Latin America. Mexico and Venezuela, the main focus of this paper, provide examples of Jewish populations generated by initially small international migration during the first half of the 20th century, and subsequent growth through further immigration and natural increase. Around the year 2000, the Jewish population was estimated at about 40,000 in Mexico, mostly concentrated in Mexico City, and 15,000 to 18,000 in Venezuela, mostly in Caracas. For many decades, Jews from Central and Eastern Europe constituted the preponderant element from the point of view of population size and internal power within these communities. -

Session of the Zionist General Council

SESSION OF THE ZIONIST GENERAL COUNCIL THIRD SESSION AFTER THE 26TH ZIONIST CONGRESS JERUSALEM JANUARY 8-15, 1967 Addresses,; Debates, Resolutions Published by the ORGANIZATION DEPARTMENT OF THE ZIONIST EXECUTIVE JERUSALEM AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE n Library י»B I 3 u s t SESSION OF THE ZIONIST GENERAL COUNCIL THIRD SESSION AFTER THE 26TH ZIONIST CONGRESS JERUSALEM JANUARY 8-15, 1966 Addresses, Debates, Resolutions Published by the ORGANIZATION DEPARTMENT OF THE ZIONIST EXECUTIVE JERUSALEM iii THE THIRD SESSION of the Zionist General Council after the Twenty-sixth Zionist Congress was held in Jerusalem on 8-15 January, 1967. The inaugural meeting was held in the Binyanei Ha'umah in the presence of the President of the State and Mrs. Shazar, the Prime Minister, the Speaker of the Knesset, Cabinet Ministers, the Chief Justice, Judges of the Supreme Court, the State Comptroller, visitors from abroad, public dignitaries and a large and representative gathering which filled the entire hall. The meeting was opened by Mr. Jacob Tsur, Chair- man of the Zionist General Council, who paid homage to Israel's Nobel Prize Laureate, the writer S.Y, Agnon, and read the message Mr. Agnon had sent to the gathering. Mr. Tsur also congratulated the poetess and writer, Nellie Zaks. The speaker then went on to discuss the gravity of the time for both the State of Israel and the Zionist Move- ment, and called upon citizens in this country and Zionists throughout the world to stand shoulder to shoulder to over- come the crisis. Professor Andre Chouraqui, Deputy Mayor of the City of Jerusalem, welcomed the delegates on behalf of the City. -

Cantemos a Coro

Cancionero Navideño Que la alegría, salud y paz reine en tu hogar en esta Navidad. Celebremos con la esperanza de un nuevo porvenir para todos. ¡Felicidades! 2 Índice de Canciones Bombas Puertorriqueñas COVID-19 3 Jardinero de cariño 18 De tierras lejanas 4 El Jolgorio 19 Levántate 4 Popurrí de Navidad 19 Si no me dan de beber 4 Traigo la salsa 20 Alegre vengo 5 Aires de Navidad 20 Caminan las nubes 5 Cantemos a coro 21 Cantares de Navidad 6 Casitas de las montaña 21 Pobre lechón 6 La escalera 22 El asalto 6 El cheque es bueno 22 El Santo Nombre de Jesús 7 Tu eres la causante de las penas mías 23 De la montaña venimos 7 Cuando las mujeres 23 Saludos, saludos 8 No quieren parranda, No quieren cantar 24 Venid pastores 8 Una noche en Borinquen / Desilución 24 A la zarandela 8 Canto a Borinquen 25 Alegría 9 Bombas 26 El fuá 9 Temporal 27 Noche de Paz 10 Cortaron a Elena 27 Feliz Navidad 10 Son Borinqueño 28 Venimos desde lejos 10 Medley de despedida 28 El Coquí 11 Dame la mano paloma 29 Mi Burrito Sabanero 11 Santa María 30 El Cardenalito 12 La suegra 30 A quién no le gusta eso 12 Asómate al balcón 31 Alegres venimos 12 Arbolito, arbolito 13 El ramillete 13 Parranda del sopón 13 El Lechón 14 Hermoso Bouquet 14 Los Peces en el Río 14 Niño Jesús 15 Yo me tomo el ron 15 Amanecer Borincano 16 La Botellita 16 Dónde vas María 17 Villancico Yaucano 17 Traigo esta trulla 18 3 Bombas Puertorriqueñas COVID-19 Compositor: Puerto Rico Public Health Trust Con la mascarilla bien puesta voy a celebrar la voy a utilizar de escudo para protegerme y a nadie -

Descendants of the Anusim (Crypto-Jews) in Contemporary Mexico

Descendants of the Anusim (Crypto-Jews) in Contemporary Mexico Slightly updated version of a Thesis for the degree of “Doctor of Philosophy” by Schulamith Chava Halevy Hebrew University 2009 © Schulamith C. Halevy 2009-2011 This work was carried out under the supervision of Professor Yom Tov Assis and Professor Shalom Sabar To my beloved Berthas In Memoriam CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................7 1.1 THE PROBLEM.................................................................................................................7 1.2 NUEVO LEÓN ............................................................................................................ 11 1.2.1 The Original Settlement ...................................................................................12 1.2.2 A Sephardic Presence ........................................................................................14 1.2.3 Local Archives.......................................................................................................15 1.3 THE CARVAJAL TRAGEDY ....................................................................................... 15 1.4 THE MEXICAN INQUISITION ............................................................................. 17 1.4.1 José Toribio Medina and Alfonso Toro.......................................................17 1.4.2 Seymour Liebman ...............................................................................................18 1.5 CRYPTO‐JUDAISM -

How They Lived to Tell 1939-1945 Edith Ruina

How They Lived to Tell 1939-1945 Together members of a Jewish youth group fled from Poland to Slovakia, Austria, Hungary, Romania and Palestine Edith Ruina Including selections from the written Recollection of Rut Judenherc, interviews and testimonies of other survivors. © Edith Ruina May 24, 2005 all rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Published 2005 Mixed Media Memoirs LLC Book design by Jason Davis [email protected] Green Bay,Wisconsin CONTENTS Acknowledgment ..............................................................................v Chapter 1 Introduction ......................................................................1 Chapter 2 1939-1942 ......................................................................9 1. The People in this Story 2. The Situation of Jews in Poland Chapter 3 1939-1942 Poland..........................................................55 Before and After the German Occupation Chapter 4 1943 Poland ..................................................................87 Many Perished—Few Escaped Chapter 5 1943-44 Austria............................................................123 Chapter 6 1944 Hungary..............................................................155 Surviving in Hungary Chapter 7 1944-1945 ..................................................................205 Romania en route to Palestine Chapter 8 Palestine ......................................................................219 They Lived to Tell v Chapter 9 ....................................................................................235 -

Jewish Behavior During the Holocaust

VICTIMS’ POLITICS: JEWISH BEHAVIOR DURING THE HOLOCAUST by Evgeny Finkel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Political Science) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN–MADISON 2012 Date of final oral examination: 07/12/12 The dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Yoshiko M. Herrera, Associate Professor, Political Science Scott G. Gehlbach, Professor, Political Science Andrew Kydd, Associate Professor, Political Science Nadav G. Shelef, Assistant Professor, Political Science Scott Straus, Professor, International Studies © Copyright by Evgeny Finkel 2012 All Rights Reserved i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation could not have been written without the encouragement, support and help of many people to whom I am grateful and feel intellectually, personally, and emotionally indebted. Throughout the whole period of my graduate studies Yoshiko Herrera has been the advisor most comparativists can only dream of. Her endless enthusiasm for this project, razor- sharp comments, constant encouragement to think broadly, theoretically, and not to fear uncharted grounds were exactly what I needed. Nadav Shelef has been extremely generous with his time, support, advice, and encouragement since my first day in graduate school. I always knew that a couple of hours after I sent him a chapter, there would be a detailed, careful, thoughtful, constructive, and critical (when needed) reaction to it waiting in my inbox. This awareness has made the process of writing a dissertation much less frustrating then it could have been. In the future, if I am able to do for my students even a half of what Nadav has done for me, I will consider myself an excellent teacher and mentor. -

פרשת במדבר Parshat B’Midbar

There’s a Place for Me at CBD! פרשת במדבר Parshat B’midbar 5 Sivan, 5775 / May 23, 2015 Triennial Cycle Year II: Numbers 2:1-3:13 Ḥumash Etz Ḥayim, page 774 Haftarah Hosea 2:1-22 1. (2:1-31) The organization and order of the Israelite camp. 2. (2:32-34) The total enrollment of the Israelites, except for the Levites: 603,550. 3. (3:1-13) The special enrollment of the Levites, their tasks, and the story of how they received their special role in place of the first-born sons. Receptionist/Front Desk 408.257.3333 Philip R. Ohriner, Senior Rabbi [email protected] 408.366.9104 Leslie Alexander, Rabbi [email protected] 408.366.9105 Tanya Lorien, Director, Operations [email protected] 408.366.9107 Barbara Biran, Director, Ritual [email protected] 408.366.9106 Monica Hernandez, Member Accounts Associate [email protected] 408.366.9108 Lynn Crocker, Mkt. and Comm. Associate [email protected] 408.366.9102 Jillian Cosgrave, Front Office Associate [email protected] 408.366.9110 Iris Bendahan, Director, Jewish Education Program [email protected] 408.366.9116 Andrea Ammerman, School Admin. Assistant [email protected] 408.366.9101 Irene Swedroe, JET (Jewish Education for Teens) [email protected] Candle lighting time for Friday, May 22, 2015, 7:57 p.m. Volunteers Needed nd Abrahamic Alliance Dinner for the Homeless Friday, May 22 This is a unique opportunity where, along with likeminded Muslims 10:00am Talmud Study (P-3A) and Christians, we will prepare a meal and serve it to more than 200 11:15am Spiritual Ethics Discussion Group (P-3A) homeless people. -

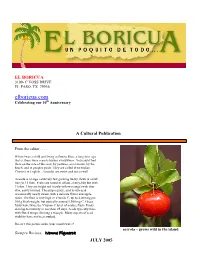

Elboricua.Com Celebrating Our 10Th Anniversary

EL BORICUA 3109- C VOSS DRIVE EL PASO, TX 79936 elboricua.com Celebrating our 10th Anniversary A Cultural Publication From the editor . When I was a child and living in Puerto Rico, a long time ago that is, there were acerola bushes everywhere. You could find them on the side of the road, by pastures, en el monte, by the beach, and in peoples yards. They are called West Indian Cherries in English. Acerolas are sweet and tart as well. Acerola is a large, relatively fast growing bushy shrub or small tree (to 15 feet). Fruits are round to oblate, cherry-like but with 3 lobes. They are bright red (rarely yellow-orange) with thin skin, easily bruised. The pulp is juicy, acid to sub-acid occasionally nearly sweet, with a delicate flavor and apple notes. The fruit is very high in Vitamin C, up to 4,000 mg per 100 g fresh weight, but typically around 1,500 mg C. Green fruits have twice the Vitamin C level of mature fruits. Fruits develop to maturity in less than 25 days. Seeds typically three with fluted wings, forming a triangle. Many aspects of seed viability have not been studied. Doesn’t this picture make your mouth water? acerola – grows wild in the island Siempre Boricua, Ivonne Figueroa JULY 2005 JULY 2005 EL BORICUA PAGE 2 EL BORICUA is Published by: - Editors and Contributors - BORICUA PUBLICATIONS El Paso, TX 79936 ©1995-2005 Boricua Publications All articles are the property of Boricua Publications or the property of its authors. Javier Figueroa -El Paso , TX Publisher Ivonne Figueroa - El Paso, TX Carmen Santos de Curran Executive Editor & Gen. -

Rejecting Hatred: Fifty Years of Catholic Dialogue with Jews and Muslims Since Nostra Aetate

Rejecting Hatred: Fifty Years of Catholic Dialogue with Jews and Muslims since Nostra Aetate The Reverend Patrick J. Ryan, S.J. Laurence J. McGinley Professor of Religion and Society Fordham University RESPONDENTS Professor Magda Teter, Ph.D. Shvidler Chair in Judaic Studies, Fordham University Professor Hussein Rashid, Ph.D. Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y. TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 10, 2015 | LINCOLN CENTER CAMPUS WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 11, 2015 | ROSE HILL CAMPUS This lecture was previously published in Origins 45 (January 7, 2016): 531-39. Rejecting Hatred: Fifty Years of Catholic Dialogue with Jews and Muslims since Nostra Aetate The Reverend Patrick J. Ryan, S.J. Laurence J. McGinley Professor of Religion and Society Fordham University A cousin of my father, a big Irishman named Tom Ryan, was ordained a priest in Rome in 1938. After his ordination he studied there for some years and made a mark for himself as one proficient not only in Latin and canon law but also in Italian. Working for the Secretariat of State, which supervises the papal diplomatic corps, Tom was eventually assigned in 1943 to Istanbul to become Secretary to the Apostolic Delegate to the Catholic bishops in Greece and Turkey. Monsignor Ryan, as he was by that time, worked very well with the Italian Apostolic Delegate, Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli, better known in later life as Pope John XXIII. Roncalli liked Tom and wrote home to his family in Italy in 1943 that his new Irish secretary “comes from good farming stock like ourselves” and also “speaks Italian just like us.”1 1 Ryan worked for Roncalli from July 1943 to late November 1944, even teaching him some English, until Ryan was eventually transferred to Cairo and Roncalli shortly afterwards to newly liberated France, where he became the Papal Nuncio and dean of the diplomatic corps.2 Bishop Ryan, as he later became, looked back on those months in Istanbul with some nostalgia. -

PDF on Heaven and Earth: Pope Francis on Faith, Family, and The

[PDF] On Heaven And Earth: Pope Francis On Faith, Family, And The Church In The Twenty-First Century Abraham Skorka, Jorge Mario Bergoglio - pdf download free book Free Download On Heaven And Earth: Pope Francis On Faith, Family, And The Church In The Twenty-First Century Full Popular Abraham Skorka, Jorge Mario Bergoglio, I Was So Mad On Heaven And Earth: Pope Francis On Faith, Family, And The Church In The Twenty-First Century Abraham Skorka, Jorge Mario Bergoglio Ebook Download, On Heaven And Earth: Pope Francis On Faith, Family, And The Church In The Twenty-First Century Free Read Online, PDF On Heaven And Earth: Pope Francis On Faith, Family, And The Church In The Twenty-First Century Full Collection, full book On Heaven And Earth: Pope Francis On Faith, Family, And The Church In The Twenty-First Century, online free On Heaven And Earth: Pope Francis On Faith, Family, And The Church In The Twenty-First Century, Download Online On Heaven And Earth: Pope Francis On Faith, Family, And The Church In The Twenty-First Century Book, On Heaven And Earth: Pope Francis On Faith, Family, And The Church In The Twenty-First Century Abraham Skorka, Jorge Mario Bergoglio pdf, the book On Heaven And Earth: Pope Francis On Faith, Family, And The Church In The Twenty-First Century, Download On Heaven And Earth: Pope Francis On Faith, Family, And The Church In The Twenty-First Century Online Free, Read On Heaven And Earth: Pope Francis On Faith, Family, And The Church In The Twenty-First Century Online Free, Read Best Book On Heaven And Earth: Pope