The Joys of Teaching Literature, Vol 4, 2013-14

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oscar-Winning 'Slumdog Millionaire:' a Boost for India's Global Image?

ISAS Brief No. 98 – Date: 27 February 2009 469A Bukit Timah Road #07-01, Tower Block, Singapore 259770 Tel: 6516 6179 / 6516 4239 Fax: 6776 7505 / 6314 5447 Email: [email protected] Website: www.isas.nus.edu.sg Oscar-winning ‘Slumdog Millionaire’: A Boost for India’s Global Image? Bibek Debroy∗ Culture is difficult to define. This is more so in a large and heterogeneous country like India, where there is no common language and religion. There are sub-cultures within the country. Joseph Nye’s ‘soft power’ expression draws on a country’s cross-border cultural influences and is one enunciated with the American context in mind. Almost tautologically, soft power implies the existence of a relatively large country and the term is, therefore, now also being used for China and India. In the Indian case, most instances of practice of soft power are linked to language and literature (including Indians writing in English), music, dance, cuisine, fashion, entertainment and even sport, and there is no denying that this kind of cross-border influence has been increasing over time, with some trigger provided by the diaspora. The film and television industry’s influence is no less important. In the last few years, India has produced the largest number of feature films in the world, with 1,164 films produced in 2007. The United States came second with 453, Japan third with 407 and China fourth with 402. Ticket sales are higher for Bollywood than for Hollywood, though revenue figures are much higher for the latter. Indian film production is usually equated with Hindi-language Bollywood, often described as the largest film-producing centre in the world. -

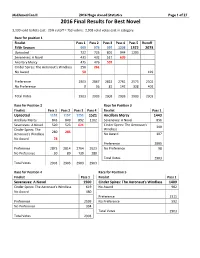

2016 Statistics Document

MidAmeriCon II 2016 Hugo Award Statistics Page 1 of 27 2016 Final Results for Best Novel 3,130 valid ballots cast. 25% cutoff = 753 voters. 2,903 valid votes cast in category. Race for position 1 Finalist Pass 1 Pass 2 Pass 3 Pass 4 Pass 5 Runoff Fifth Season 969 973 997 1208 1372 2073 Uprooted 722 725 801 944 1203 Seveneves: A Novel 431 432 517 609 Ancillary Mercy 475 476 507 Cinder Spires: The Aeronaut's Windlass 256 261 No Award 50 429 Preference 2903 2867 2822 2761 2575 2502 No Preference 0 36 81 142 328 401 Total Votes 2903 2903 2903 2903 2903 2903 Race for Position 2 Race for Position 3 Finalist Pass 1 Pass 2 Pass 3 Pass 4 Finalist Pass 1 Uprooted 1152 1157 1251 1521 Ancillary Mercy 1443 Ancillary Mercy 843 849 892 1102 Seveneves: A Novel 856 Seveneves: A Novel 520 523 621 Cinder Spires: The Aeronaut's 399 Cinder Spires: The Windlass 280 285 Aeronaut's Windlass No Award 107 No Award 78 Preference 2805 Preference 2873 2814 2764 2623 No Preference 98 No Preference 30 89 139 280 Total Votes 2903 Total Votes 2903 2903 2903 2903 Race for Position 4 Race for Position 5 Finalist Pass 1 Finalist Pass 1 Seveneves: A Novel 1500 Cinder Spires: The Aeronaut's Windlass 1409 Cinder Spires: The Aeronaut's Windlass 619 No Award 902 No Award 480 Preference 2311 Preference 2599 No Preference 592 No Preference 304 Total Votes 2903 Total Votes 2903 MidAmeriCon II 2016 Hugo Award Statistics Page 2 of 27 2016 Final Results for Best Novella 3,130 valid ballots cast. -

Diamonds-Are-Forever-Worksheet

Pre-Intermediate Level Worksheet Diamonds Are Forever Ian Fleming A Before Reading 1 Ian Fleming wrote Diamonds Are Forever. What do you know about his life? Match the questions 1–8 to the answers a–h. 1 When was Ian Fleming born? a Dr No 2 What was his first job? b 1964 3 What was his second job? c 1929 4 When did he go to Moscow? d a soldier 5 When did he finish his first book? e 1908 6 What was the title of his first novel? f Casino Royale 7 Which book was the first to be made into a film? g a journalist 8 When did he die? h 1952 Read ‘A Note About The Author’ at the beginning of the book to check your answers. 2 The hero of the story is James Bond. What James Bond films do you know? And what do you know about his appearance, character and lifestyle? Write your ideas in the boxes below. Films Appearance Character Lifestyle Macmillan Readers Diamonds Are Forever 1 This page has beenbeen downloadeddownloaded fromfrom www.macmillanenglish.com.www.macmillanenglish.com. ItIt isis photocopiable,photocopiable, but but all all copies copies must must be be complete complete pages. pages. © Macmillan PublishersPublishers LimitedLimited 2009.2013. Published by Macmillan Heinemann ELT. Heinemann is a registered trademark of Pearson Education, used under licence. Pre-Intermediate Level Worksheet 3 Look at the pictures of the characters on page 6 of the book. Which people do you think are ‘good’ and which are ‘bad’? Check your answers as you read. -

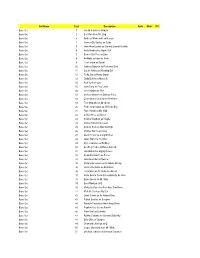

Set Name Card Description Auto Mem #'D Base Set 1 Harold Sakata As Oddjob Base Set 2 Bert Kwouk As Mr

Set Name Card Description Auto Mem #'d Base Set 1 Harold Sakata as Oddjob Base Set 2 Bert Kwouk as Mr. Ling Base Set 3 Andreas Wisniewski as Necros Base Set 4 Carmen Du Sautoy as Saida Base Set 5 John Rhys-Davies as General Leonid Pushkin Base Set 6 Andy Bradford as Agent 009 Base Set 7 Benicio Del Toro as Dario Base Set 8 Art Malik as Kamran Shah Base Set 9 Lola Larson as Bambi Base Set 10 Anthony Dawson as Professor Dent Base Set 11 Carole Ashby as Whistling Girl Base Set 12 Ricky Jay as Henry Gupta Base Set 13 Emily Bolton as Manuela Base Set 14 Rick Yune as Zao Base Set 15 John Terry as Felix Leiter Base Set 16 Joie Vejjajiva as Cha Base Set 17 Michael Madsen as Damian Falco Base Set 18 Colin Salmon as Charles Robinson Base Set 19 Teru Shimada as Mr. Osato Base Set 20 Pedro Armendariz as Ali Kerim Bey Base Set 21 Putter Smith as Mr. Kidd Base Set 22 Clifford Price as Bullion Base Set 23 Kristina Wayborn as Magda Base Set 24 Marne Maitland as Lazar Base Set 25 Andrew Scott as Max Denbigh Base Set 26 Charles Dance as Claus Base Set 27 Glenn Foster as Craig Mitchell Base Set 28 Julius Harris as Tee Hee Base Set 29 Marc Lawrence as Rodney Base Set 30 Geoffrey Holder as Baron Samedi Base Set 31 Lisa Guiraut as Gypsy Dancer Base Set 32 Alejandro Bracho as Perez Base Set 33 John Kitzmiller as Quarrel Base Set 34 Marguerite Lewars as Annabele Chung Base Set 35 Herve Villechaize as Nick Nack Base Set 36 Lois Chiles as Dr. -

1 Dr. No, 1962 #2 from Russia with Love, 1963

1111//2277//22001155 LLiissttoof fAAlll lJJaammees sBBoonnd dMMoov viieess Search Site: Search Follow usus on on Twitter Like usus on on Facebook Lists Top 10s Characters Cast Gadgets Movies Quotes More List of All James Bond Movies The complete list of official James Bond films, made by EON Productions. Beginning with Sean Connery, and going through George Lazenby, Roger Moore, Timothy Dalton, Pierce Brosnan and Daniel Craig. Have you ever wondered how many James Bond movies there are? The new film, Spectre, will be released October 2015. #1 Dr. No, 1962 James Bond: Sean Connery Bond Girl: Honey Ryder Director: Terence Young Running Time: 110 Minutes Synopsis: Dr. No was the first 007 film produced by EON Productions. Bond is sent to Jamaica to investigate the death of MI6 agent John Strangways. He finds his way to Crab Key island, where the mysterious Dr. No awaits. ##22 From Russia With Love, 1963 James Bond: Sean Connery Bond Girl: Tatiana Romanova Director: Terence Young Running Time: 115 Minutes Synopsis: When MI6 gets a chance to get their hands on a Lektor decoder, Bond is sent to Turkey to seduce the beautiful Tatiana, and bring back the machine. With the help of Kerim Bey, Bond escapes on the Orient Express, but might not make it off alive. hhttttpp::////wwwwww..000077jjaammeess..ccoomm//aarrttiicclleess//lliisstt__ooff__jjaammeess__bboonndd__mmoovviieess..pphhpp 11//44 1111//2277//22001155 LLiissttoof fAAlll lJJaammees sBBoonnd dMMoov viieess #3 Goldfinger, 1964 James Bond: Sean Connery Bond Girl: Pussy Galore Director: Guy Hamilton Running Time: 110 Minutes Synopsis: The Bank of England has detected an unauthorized leakage of gold from the country, and Bond is sent to investigate. -

Catalogue XV 116 Rare Works of Speculative Fiction

Catalogue XV 116 Rare Works Of Speculative Fiction About Catalogue XV Welcome to our 15th catalogue. It seems to be turning into an annual thing, given it was a year since our last catalogue. Well, we have 116 works of speculative fiction. Some real rarities in here, and some books that we’ve had before. There’s no real theme, beyond speculative fiction, so expect a wide range from early taproot texts to modern science fiction. Enjoy. About Us We are sellers of rare books specialising in speculative fiction. Our company was established in 2010 and we are based in Yorkshire in the UK. We are members of ILAB, the A.B.A. and the P.B.F.A. To Order You can order via telephone at +44(0) 7557 652 609, online at www.hyraxia.com, email us or click the links. All orders are shipped for free worldwide. Tracking will be provided for the more expensive items. You can return the books within 30 days of receipt for whatever reason as long as they’re in the same condition as upon receipt. Payment is required in advance except where a previous relationship has been established. Colleagues – the usual arrangement applies. Please bear in mind that by the time you’ve read this some of the books may have sold. All images belong to Hyraxia Books. You can use them, just ask us and we’ll give you a hi-res copy. Please mention this catalogue when ordering. • Toft Cottage, 1 Beverley Road, Hutton Cranswick, UK • +44 (0) 7557 652 609 • • [email protected] • www.hyraxia.com • Aldiss, Brian - The Helliconia Trilogy [comprising] Spring, Summer and Winter [7966] London, Jonathan Cape, 1982-1985. -

SYBAMMC Corporate Communication & Public

SYBAMMC_Corporate Communication & Public Relations_Sem III_odd Sem 1) Appropriation of a person’s name or likeness for commercial or trade purposes without permission is ____and may be a violation of a person’s right to publicity a) Libel b) Copyright c) Slander d) Invasion of privacy 2) Public relations is a deliberate, planned and sustained effort to establish and maintain mutual understanding between an organization and its______ a) Media b) Economy c) Publics d) Society 3) ____are the two most important public relations tools for maintaining good stockholder relations. a) Annual reports & stockholder meetings b) Annual reports & press release c) House journals & stock holder meetings d) Newsletter & house journals 4) ______is the oldest form of public relations. a) Two-way asymmetrical b) Two-way symmetrical c) Press agentry d) Public information 5) ____are the two most important public relations tools for maintaining good stockholder relations. e) Annual reports & stockholder meetings f) Annual reports & press release g) House journals & stock holder meetings h) Newsletter & house journals 6) ______acts as watchdog for society. a) Management b) Technology c) Employees d) Media 7) A company that is “responsibly addressing _____of key publics and communities’ increase the public admiration of the organizations. a) Technological concerns b) Information sharing c) Profit sharing d) Environmental concerns 8) ________is a commanding force in managing the attitude of the general public towards organizations. a) Management b) Employees c) Technology d) Media 9) _____messages helps make lasting impact and favourable impression of an organizations and its products on stakeholders. a) Consistent b) Inconsistent c) Incoherent d) Irrational 10) Corporate communication is ___in nature a) Simple b) Complex c) Plain d) Symmetric 11) Shareholders, board members and employees are______stakeholders. -

A Queer Analysis of the James Bond Canon

MALE BONDING: A QUEER ANALYSIS OF THE JAMES BOND CANON by Grant C. Hester A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL May 2019 Copyright 2019 by Grant C. Hester ii MALE BONDING: A QUEER ANALYSIS OF THE JAMES BOND CANON by Grant C. Hester This dissertation was prepared under the direction of the candidate's dissertation advisor, Dr. Jane Caputi, Center for Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, Communication, and Multimedia and has been approved by the members of his supervisory committee. It was submitted to the faculty of the Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters and was accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Khaled Sobhan, Ph.D. Interim Dean, Graduate College iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Jane Caputi for guiding me through this process. She was truly there from this paper’s incubation as it was in her Sex, Violence, and Hollywood class where the idea that James Bond could be repressing his homosexuality first revealed itself to me. She encouraged the exploration and was an unbelievable sounding board every step to fruition. Stephen Charbonneau has also been an invaluable resource. Frankly, he changed the way I look at film. His door has always been open and he has given honest feedback and good advice. Oliver Buckton possesses a knowledge of James Bond that is unparalleled. I marvel at how he retains such information. -

MPPSC PRELIMS the Only Comprehensive “CURRENT AFFAIRS” Magazine of “MADHYA PRADESH”In “ENGLISH MEDIUM”

MPPSC PRELIMS The Only Comprehensive “CURRENT AFFAIRS” Magazine of “MADHYA PRADESH”in “ENGLISH MEDIUM” National International MADHYA CURRENT Economy PRADESH MP Budget Current Affairs AFFAIRS MP Eco Survey MONTHLY Books-Authors Science Tech Personalities & Environment Sports OCTOBER 2020 Contact us: mppscadda.com [email protected] Call - 8368182233 WhatsApp - 7982862964 Telegram - t.me/mppscadda OCTOBER 2020 (CURRENT AFFAIRS) 1 MADHYA PRADESH NEWS Best wishes on International day of Older Persons Chief Minister Shri Shivraj Singh Chouhan has extended his best wishes on the International Day of Older Persons. He said that the elderly or senior persons have life experiences. They have the capacity to resolve many complicated problems. The biggest thing is that our elders have the qualities of patience, humility, ability, decision making and above all, the acquired knowledge that can give a direction to the society. Our youth must respect the elders. Their teachings must be imbibed in our lives. Chief Minister said that the elders are our heritage. Many legal provisions have been made for their honour and protection. Chief Minister has extended his best wishes to all senior citizens and elders on Senior Citizens day. Photos telling the story of Corona period Chief Minister Shri Shivraj Singh Chouhan today awarded the winners of the state level photo contest based on Covid-19 in a programme organized at Manas Bhawan and congratulated the photographers. Also inaugurated an exhibition of photographs clicked by press photographers of the state during the Corona period. Chief Minister Shri Chouhan said that the creativity of the photographers during Covid-19 crisis is apparent in this exhibition. -

CSAP Daily-CA 15-16-10-2020

CIVIL SERVICES ACHIEVERS' POINT, GUWAHATI THE ASSAM TRIBUNE ANALYSIS Date – 15 & 16 October 2020 (For Preliminary and Mains Examination) As per New Pattern of APSC (Also useful for UPSC and other State Level Government Examinations) Join our Regular/Online Classes. For details contact 8811877068 CIVIL SERVICES ACHIEVERS' POINT, GUWAHATI ANSWERS to MCQs of 14-10-2020 1. (b) Louis Gluck 2. (c) World Bank 3. (c) Stockholm Convention 4. (c) Mauritius 5. (d) All Join our Regular/Online Classes. For details contact 8811877068 CIVIL SERVICES ACHIEVERS' POINT, GUWAHATI MCQs of 16-10-2020 1. Which country has partnered with 2. Which state has launched the Mukhya Mantri Meghalaya for setting up “ centre of Saur Swarojgar Yojana? Excellence” on high value vegetables? a) Bihar b) Uttarakhand a) France c) Uttar Pradesh b) Israel d) Jharkhand c) Singapore d) South Korea Join our Regular/Online Classes. For details contact 8811877068 CIVIL SERVICES ACHIEVERS' POINT, GUWAHATI 3. Which of the following has been 4. Which Bank has inked MoU with NABARD for awarded the Nobel peace Prize 2020? extending credit support to the agricultural a) World Food Programme organizations various projects? b) United Nations High commissioner for a) State bank of India Refugees b) Punjab National Bank c) Jacinda Ardern c) World Bank d) Greta Thunberg d) Asian Development bank Join our Regular/Online Classes. For details contact 8811877068 CIVIL SERVICES ACHIEVERS' POINT, GUWAHATI 5. What causes Crimean- Congo hemorrhagic fever? a) Food Contamination b) Tick- borne virus (Nairovirus) c) Zoonosis d) Fecal- oral Join our Regular/Online Classes. For details contact 8811877068 CIVIL SERVICES ACHIEVERS' POINT, GUWAHATI CONTENTS Nepal re-elected to UN human rights council WPI rises to 1.32 percent Cabinet okays new STAR project Great Barrier Reef has lost more than half of its corals in past 3 decades:study NRL, GAIL sign Pipeline Right to Use sharing pact India to gift submarine to Myanmar Bhanu Athaiya no more Join our Regular/Online Classes. -

Download File

ArtConnect corrected_Layout 3 6/24/2013 5:29 PM Page 43 The poster of Zabak (1961) directed by Homi Wadia. Out of Sight: Archiving Hidden Histories of Practice Debashree Mukherjee All photographs courtesy Priya Paul Our understanding of Indian cinema would remain incomplete until we acknowledged its supporting cast of hairdressers, poster painters, costume designers, still photographers, makeup artists and numerous other specialists invisible to the public eye. In January 2013, Debashree Mukherjee curated an exhibition of Hindi film memorabilia titled ‘Maya Mahal’, which featured artefacts from the private collection of Priya Paul, Chairperson of Apeejay Surrendra Park Hotels. In this essay, Mukherjee uses examples from the collection to point to hidden histories of work and practice, and to give us a fragmented view of low-budget films, lost genres and the wage-workers who mark each film with their individual skills. ArtConnect corrected_Layout 3 6/24/2013 5:29 PM Page 44 ArtConnect: The IFA Magazine, Volume 7, Number 1 eterodox in its scope and the elemental contract of cinema range, Priya Paul’s itself: to deliver sensory excitement, Hcollection of film voyeuristic delight and magical memorabilia represents an eccentric worlds. Thus, the exhibition mix of films. There are archives larger showcased genres, practitioners and than this, there are archives that are aesthetics that are often forgotten in more systematic, but the pleasure of a bid to celebrate auteurs and ‘classics’. serendipity springs from This is an alternative history of juxtaposition, not from order and Hindi cinema—one that is decidedly expanse. Comprising approximately excessive, melodramatic, even 5,000 paper artefacts, the Priya Paul utopian. -

Unit-2 Silent Era to Talkies, Cinema in Later Decades

Bachelor of Arts (Honors) in Journalism& Mass Communication (BJMC) BJMC-6 HISTORY OF THE MEDIA Block - 4 VISUAL MEDIA UNIT-1 EARLY YEARS OF PHOTOGRAPHY, LITHOGRAPHY AND CINEMA UNIT-2 SILENT ERA TO TALKIES, CINEMA IN LATER DECADES UNIT-3 COMING OF TELEVISION AND STATE’S DEVELOPMENT AGENDA UNIT-4 ARRIVAL OF TRANSNATIONAL TELEVISION; FORMATION OF PRASAR BHARATI The Course follows the UGC prescribed syllabus for BA(Honors) Journalism under Choice Based Credit System (CBCS). Course Writer Course Editor Dr. Narsingh Majhi Dr. Sudarshan Yadav Assistant Professor Assistant Professor Journalism and Mass Communication Dept. of Mass Communication, Sri Sri University, Cuttack Central University of Jharkhand Material Production Dr. Manas Ranjan Pujari Registrar Odisha State Open University, Sambalpur (CC) OSOU, JUNE 2020. VISUAL MEDIA is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licences/by-sa/4.0 Printedby: UNIT-1EARLY YEARS OF PHOTOGRAPHY, LITHOGRAPHY AND CINEMA Unit Structure 1.1. Learning Objective 1.2. Introduction 1.3. Evolution of Photography 1.4. History of Lithography 1.5. Evolution of Cinema 1.6. Check Your Progress 1.1.LEARNING OBJECTIVE After completing this unit, learners should be able to understand: the technological development of photography; the history and development of printing; and the development of the motion picture industry and technology. 1.2.INTRODUCTION Learners as you are aware that we are going to discuss the technological development of photography, lithography and motion picture. In the present times, the human society is very hard to think if the invention of photography hasn‘t been materialized. It is hard to imagine the world without photography.