Paleo Newsletter 6(2)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agate Fossil Beds National Monument: a Proposal

a frMrfxteaC Tincted Sfatei. 'Hattattat 'Pa'16, Service Cover: FOSSIL SLAB FROM THE AGATE QUARRIES Courtesy University of Nebraska State Museum ANCIENT LIFE AT THE AGATE SITE Illustration by Charles R. Knight Courtesy Chicago Natural History Museum PROPOSED AGATE FOSSIL BEDS NATIONAL MONUMENT NEBRASKA August 1963 Department of the Interior National Park Service Midwest Region Omaha, Nebraska Created in I8U9, the Department of the Interior— America's Department of Natural Resources—is concerned with the management, conservation, and development of the Nation's water, wildlife, mineral, forest, and park and recreational resources. It also has major responsibilities for Indian and Territorial affairs. As the Nation's principal conservation agency, the Department works to assure that nonrenewable re sources are developed and used wisely, that park and recreational resources make their full contri bution to the progress, prosperity, and security of the United States—now and in the future. CONTENTS Page Introduction 1 The Setting 3 Geologic History 7 Fossil Collecting History 23 The Cook Family - Early Pioneers of the West 29 Significance 33 Suitability 35 Feasibility 38 Conclusions and Recommendations 39 Proposed Development and Use kl The Proposed Area and Its Administration k6 Acknowledgements k7 Bibliography kQ Fifteen Million Years Ago in Western Nebraska From an illustration by Erwin Christinas Courtesy Natural History Magazine INTRODUCTION The Agate Springs Fossil Quarries site located in Sioux County, Nebraska, is world renowned for its rich concentrations of the fossil remains of mammals that lived fifteen million years ago. A study of this site was made by the Midwest Region, National Park Service in the fall of i960, and a preliminary report prepared. -

Origin and Beyond

EVOLUTION ORIGIN ANDBEYOND Gould, who alerted him to the fact the Galapagos finches ORIGIN AND BEYOND were distinct but closely related species. Darwin investigated ALFRED RUSSEL WALLACE (1823–1913) the breeding and artificial selection of domesticated animals, and learned about species, time, and the fossil record from despite the inspiration and wealth of data he had gathered during his years aboard the Alfred Russel Wallace was a school teacher and naturalist who gave up teaching the anatomist Richard Owen, who had worked on many of to earn his living as a professional collector of exotic plants and animals from beagle, darwin took many years to formulate his theory and ready it for publication – Darwin’s vertebrate specimens and, in 1842, had “invented” the tropics. He collected extensively in South America, and from 1854 in the so long, in fact, that he was almost beaten to publication. nevertheless, when it dinosaurs as a separate category of reptiles. islands of the Malay archipelago. From these experiences, Wallace realized By 1842, Darwin’s evolutionary ideas were sufficiently emerged, darwin’s work had a profound effect. that species exist in variant advanced for him to produce a 35-page sketch and, by forms and that changes in 1844, a 250-page synthesis, a copy of which he sent in 1847 the environment could lead During a long life, Charles After his five-year round the world voyage, Darwin arrived Darwin saw himself largely as a geologist, and published to the botanist, Joseph Dalton Hooker. This trusted friend to the loss of any ill-adapted Darwin wrote numerous back at the family home in Shrewsbury on 5 October 1836. -

Mcabee Fossil Site Assessment

1 McAbee Fossil Site Assessment Final Report July 30, 2007 Revised August 5, 2007 Further revised October 24, 2008 Contract CCLAL08009 by Mark V. H. Wilson, Ph.D. Edmonton, Alberta, Canada Phone 780 435 6501; email [email protected] 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary ..............................................................................................................................................................3 McAbee Fossil Site Assessment ..........................................................................................................................................4 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................................4 Geological Context ...........................................................................................................................................................8 Claim Use and Impact ....................................................................................................................................................10 Quality, Abundance, and Importance of the Fossils from McAbee ............................................................................11 Sale and Private Use of Fossils from McAbee..............................................................................................................12 Educational Use of Fossils from McAbee.....................................................................................................................13 -

Fossil Plantsplants Colorado

National Park Service Florissant Fossil Beds U.S. Department of the Interior Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument Fossil PlantsPlants Colorado More than 130 plant species have been described from Florissant. These are represented by leaves, fruits, flowers, seeds, wood, and pollen, yet the only fossils most visitors see are the stumps of ancient redwood trees. Why is this? Fossilization is a complex process that can be affected by a number of factors, and multiple forms of fossilization took place during Eocene Florissant. How were the fossil plants preserved? Most of the plant diversity at Florissant comes from the abundance of plants preserved in shale. The volcanic mudflow that preserved the redwood stumps was very high-energy, meaning that only the most durable plant parts, such as trunks, cones, and seeds, survived the flow intact. More Species like Sequoia (redwood, left) were preserved delicate plant parts like leaves frequently because they lived in wet valley bottoms near the and flowers were preserved lake. Pine (above left), mountain mahogany (above center), poorly or not at all. and oak (above right), which are seen less frequently as Delicate plant parts were deposited at the bottom of Lake Floris- fossils, lived on more distant hillsides. sant, a low-energy, low-oxygen environment. Their fine features are The abundance of certain species also plays a role in how preserved in paper shale, a very fine grained rock produced by the often they are preserved. Fagopsis longifolia, the most deposition of volcanic ash and a kind of microscopic algae called common fossil plant found at Florissant, is an understory tree diatoms. -

Agate Fossil Beds

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers National Park Service 1980 Agate Fossil Beds Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natlpark "Agate Fossil Beds" (1980). U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers. 160. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natlpark/160 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the National Park Service at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Agate Fossil Beds cap. tfs*Af Clemson Universit A *?* jfcti *JpRPP* - - - . Agate Fossil Beds Agate Fossil Beds National Monument Nebraska Produced by the Division of Publications National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. 1980 — — The National Park Handbook Series National Park Handbooks, compact introductions to the great natural and historic places adminis- tered by the National Park Service, are designed to promote understanding and enjoyment of the parks. Each is intended to be informative reading and a useful guide before, during, and after a park visit. More than 100 titles are in print. This is Handbook 107. You may purchase the handbooks through the mail by writing to Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington DC 20402. About This Book What was life like in North America 21 million years ago? Agate Fossil Beds provides a glimpse of that time, long before the arrival of man, when now-extinct creatures roamed the land which we know today as Nebraska. -

Characterization of Hydraulic Properties Of

Final Report for Award No. DE-FG03-94ER14462 1 Structural Heterogeneities and Paleo Fluid Flow in an Analog Sandstone Reservoir 2001-2004 By David Pollard and Atilla Aydin Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences Stanford University Stanford, California DOE, BES, and Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences Division Final Report for Award No. DE-FG03-94ER14462 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................................................2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.........................................................................................................................................3 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ...............................................................................................................4 GEOLOGIC AND STRUCTURAL SETTING .....................................................................................................................4 Regional Geology.................................................................................................................................................4 Principal Structural Elements of the Aztec Sandstone.........................................................................................5 SUMMARY RESULTS FROM THE GRANT PERIOD ........................................................................................6 1. CHEMICAL CHARACTERIZATION OF COLORED ALTERATION BANDS AND PALEO FLUID FLOW .................................6 2. CHARACTERIZING -

A Review of Paleobotanical Studies of the Early Eocene Okanagan (Okanogan) Highlands Floras of British Columbia, Canada and Washington, USA

Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences A review of paleobotanical studies of the Early Eocene Okanagan (Okanogan) Highlands floras of British Columbia, Canada and Washington, USA. Journal: Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Manuscript ID cjes-2015-0177.R1 Manuscript Type: Review Date Submitted by the Author: 02-Feb-2016 Complete List of Authors: Greenwood, David R.; Brandon University, Dept. of Biology Pigg, KathleenDraft B.; School of Life Sciences, Basinger, James F.; Dept of Geological Sciences DeVore, Melanie L.; Dept of Biological and Environmental Science, Keyword: Eocene, paleobotany, Okanagan Highlands, history, palynology https://mc06.manuscriptcentral.com/cjes-pubs Page 1 of 70 Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 1 A review of paleobotanical studies of the Early Eocene Okanagan (Okanogan) 2 Highlands floras of British Columbia, Canada and Washington, USA. 3 4 David R. Greenwood, Kathleen B. Pigg, James F. Basinger, and Melanie L. DeVore 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Draft 12 David R. Greenwood , Department of Biology, Brandon University, J.R. Brodie Science 13 Centre, 270-18th Street, Brandon, MB R7A 6A9, Canada; 14 Kathleen B. Pigg , School of Life Sciences, Arizona State University, PO Box 874501, 15 Tempe, AZ 85287-4501, USA [email protected]; 16 James F. Basinger , Department of Geological Sciences, University of Saskatchewan, 17 Saskatoon, SK S7N 5E2, Canada; 18 Melanie L. DeVore , Department of Biological & Environmental Sciences, Georgia 19 College & State University, 135 Herty Hall, Milledgeville, GA 31061 USA 20 21 22 23 Corresponding author: David R. Greenwood (email: [email protected]) 1 https://mc06.manuscriptcentral.com/cjes-pubs Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Page 2 of 70 24 A review of paleobotanical studies of the Early Eocene Okanagan (Okanogan) 25 Highlands floras of British Columbia, Canada and Washington, USA. -

Washington Geology, V. 23, No. 3, September 1995

w V 0 WASHINGTON w VOL. 23, NO. 3 SEPTEMBER 1995 G EOLOG"I • INSIDE THIS ISSUE 1 Early Tertiary flowers, fruits. and seeds of Washington State and adjacent areas, p. 3 WASHINGTON STATE DEPARTMENTOF 1 Selected additions to the library of the Division of Geology and Earth Resources, p. 18 Natural Resources Jennifer M . Belcher - Co mmissio ner of Public Lands Kaleen Cottingham - Supervisor WASHINGTON Crown Jewel Project Reaches Milestone GEOLOGY Vol. 23, No. 3 Raymond Lasmanis, State Geologist September 1995 Washington Department of Natural Resources Division of Geology and Earth Resources Washi11g1011 Ceologr (ISSN 1058-2134) is published four times PO Box 47007, Olympia, WA 98504-7007 each year hy (he Washington State Department or Natural Resources, Division of Geology and Earth Resources. Thi~ puh lication is free upon request. The Division al so publishes b1il lc tins. information circulars. reports or investigations. geologic maps. and open -file reports. /\ li~t o r these publications will he A rter a lengthy evaluation process under the National Envi sent upon rcquc~l. ronment Policy Act (NEPA) and the State Environment Policy Act (SEPA), on June 30, 1995, the Draft Environmental Tm DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES pac t Statement. Crown Jewel Mine, Okanogan County, Wash ington, was issued by the lead agencies, U.S. Department of Raymo nd Lasmanis. Sr,11e Ge,,J,,,;i.<1 J. Eric Schuster. /1,1 l'i.1t1111t S rate Geolo,;isr Agriculture Forest ServiL:e allll the Washington State Deparr W1lli:1m S . Lingley, Jr., Ax,,i.<1111, t Stare G,•,,/o,;isr ment of Ecology. -

Aplodontid, Sciurid, Castorid, Zapodid and Geomyoid Rodents of the Rodent Hill Locality, Cypress Hills Formation, Southwest Saskatchewan

APLODONTID, SCIURID, CASTORID, ZAPODID AND GEOMYOID RODENTS OF THE RODENT HILL LOCALITY, CYPRESS HILLS FORMATION, SOUTHWEST SASKATCHEWAN A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in the Department of Geological Sciences University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Sean D. Bell © Copyright Sean D. Bell, December 2004. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Master’s degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the libraries of the University of Saskatchewan may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department of Geological Sciences or the Dean of the College of Graduate Studies and Research. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Geological Sciences 114 Science Place University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5E2 i ABSTRACT The Rodent Hill Locality is a fossil-bearing site that is part of the Cypress Hills Formation, and is located roughly 15 km northwest of the town of Eastend, Saskatchewan. -

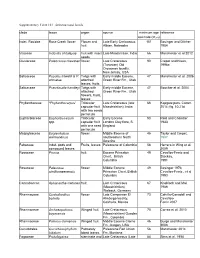

Supplementary Table 10.1. Selected Rosid Fossils Clade Taxon Organ Source Minimum Age Reference Estimate (Mya) Indet

Supplementary Table 10.1. Selected rosid fossils clade taxon organ source minimum age reference estimate (Mya) Indet. Rosidae Rose Creek flower Flower and Late Early Cretaceous 101 Basinger and Dilcher fruit Albian, Nebraska 1984 Vitaceae Indovitis chitaleyae fruit with intact Late Maastrictian, India 66 Manchester et al 2012 seeds Clusiaceae Paleoclusia chevalieri flower Late Cretaceous 90 Crepet and Nixon, (Turonian) Old 1998a Crossman locality, New Jersey, USA Salicaceae Populus tidwellii & P. Twigs with Early middle Eocene, 47 Manchester et al. 2006 wilmatae attached Green River Fm., Utah leaves, fruits Salicaceae Pseudosalix handleyi Twigs with Early middle Eocene, 47 Boucher et al. 2004 attached Green River Fm., Utah flowers, fruits, leaves Phyllanthaceae “Phyllanthocarpus” Trilocular Late Cretaceous (late 66 Kapgate pers. Comm. capsular fruit Maastrichtian), India 2014; fig. 10.21d with two seeds per locule Euphorbiaceae Euphorbiocarpon Trilocular Early Eocene 50 Reid and Chandler spp. capsular fruit London Clay flora, S. 1933 with one seed England per locule Malpighiaceae Eoglandulosa flower Middle Eocene of 45 Taylor and Crepet, warmanensis southeastern North 1987 America Fabaceae Indet. pods and Fruits, leaves Paleocene of Colombia 58 Herrera in Wing et al. compound leaves 2009 Rosaceae Prunus fruit Eocene Princeton 49 Cevallos-Ferriz and Chert, British Stockey, Columbia 1991 Rosaceae Paleorosa flower Middle Eocene 49 Basinger 1976; similkameenensis Princeton Chert, British Cevallos-Ferriz , et al Columbia 1993 Cannabaceae Aphananthe cretacea fruit Late Cretaceous 67 Knobloch and Mai (Maastrichtian) 1986 Walbeck, Germany Rhamnaceae Coahuilanthus flower Late Campanian El 73 Calvillo-Canadell and belinda Almácigo locality, Cevallos- Coahuila, Mexico Ferriz 2007 Rhamnaceae Archaeopaliurus Winged fruit Late Cretaceous 70 Correa et al. -

Cranial Morphology of the Oligocene Beaver Capacikala Gradatus from the John Day Basin and Comments on the Genus

Palaeontologia Electronica palaeo-electronica.org Cranial morphology of the Oligocene beaver Capacikala gradatus from the John Day Basin and comments on the genus Clara Stefen ABSTRACT The cranial morphology of the small Oligocene beaver Capacikala gradatus is described on the basis of a well preserved, nearly complete skull and partial mandibles from the John Day Formation, John Day Fossil Beds, Oregon, USA. The only nearly complete skull known so far from the same area as the type specimen is described here in detail. This is especially appropriate as the type specimen comes from an unknown locality within the John Day Formation and is only a fragmentary skull. The newly described specimen was found between dated marker beds, so that it can be no older than 28.7 Ma, nor younger than 27.89 Ma. Although Capacikala had been named 50 years ago (MacDonald, 1963), it is still not well known. Morphological comparisons are made to other mentioned or illustrated specimens of Capacikala, Palaeocastor and recent Castor; there are similarities and differences to both genera. The findings of the skull is discussed in comparison to the description of the genera Capacikala and Palaeocastor and some characters are revised. A phylogenetic analysis with few selected castorid species was performed, but resulted in poorly supported trees. How- ever, a complete revision of beaver phylogeny and of the characters used is beyond the scope of the paper. Clara Stefen. Senckenberg Naturhistorische Sammlungen Dresden, Museum of Zoology, Königsbrücker Landstrasse 159, 01109 Dresden, Germany, [email protected] KEY WORDS: Castoridae; Palaeocastorinae; skull; Tertiary INTRODUCTION Fremd et al., 1994; Hunt and Stepleton, 2004; Samuels and Zancanella, 2011). -

Retallack and Samuels 2020 John

Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ujvp20 Paleosol-based inference of niches for Oligocene and early miocene fossils from the John Day Formation of Oregon Gregory J. Retallack & Joshua X. Samuels To cite this article: Gregory J. Retallack & Joshua X. Samuels (2020): Paleosol-based inference of niches for Oligocene and early miocene fossils from the John Day Formation of Oregon, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2019.1761823 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2019.1761823 View supplementary material Published online: 16 Jun 2020. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ujvp20 Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology e1761823 (17 pages) © by the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2019.1761823 ARTICLE PALEOSOL-BASED INFERENCE OF NICHES FOR OLIGOCENE AND EARLY MIOCENE FOSSILS FROM THE JOHN DAY FORMATION OF OREGON GREGORY J. RETALLACK*,1 and JOSHUA X. SAMUELS2 1Department of Earth Sciences, University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon 97403, U.S.A., [email protected]; 2Department of Geosciences, East Tennessee State University, Johnson City, Tennessee 37614, U.S.A., [email protected] ABSTRACT—Over the past decade, we recorded exact locations of in situ fossils and measured calcareous nodules in paleosols of the Oligocene and lower Miocene (Whitneyan–Arikareean) John Day Formation of Oregon. These data enable precise biostratigraphy within an astronomical time scale of Milankovitch obliquity cycles and also provide mean annual precipitation and vegetation for each species.