Unit 1 Snake Biology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queen Snake, Regina Septemvittata

Queen Snake, Regina septemvittata Status: State: Endangered Federal: Not listed Identification This slender snake can reach lengths of 16-24 in. (41-61 cm) when fully grown. The dorsal (or upper) surface of a queen snake is a solid, grayish-brown color. A yellow band is present on the lower half of the body and extends from the snake’s chin to its tail. The belly of the snake is a white to yellow color with four characteristic stripes that make for easy identification. Of these four stripes, the two outer stripes are visibly thicker than the inner pair. Queen snakes have keeled scales and an © Rudolf G. Arndt anal plate that is divided. Habitat This species is highly aquatic and a very adept swimmer. Authorities report that swiftly flowing creeks, brooks and streams are the preferred habitat for queen snakes (Wright and Wright 1957). But finding them along the edges of more slowly flowing rivers and streams, and sometimes lakes, is not uncommon in some states. The queen snake’s diet (see below) always keeps it close to water, where it can sometimes be seen with just its head above the surface of the water. On occasion, a lucky observer might find these snakes basking in high numbers along the banks of streams and even hanging from streamside vegetation (Golden, personal observation). Such aggregations are probably unlikely in New Jersey, however. The best strategy for finding this species in the state would be to look under flat rocks and other debris along the banks of the Delaware River and its tributaries. -

Venomous Snakes in Pennsylvania the First Question Most People Ask When They See a Snake Is “Is That Snake Poisonous?” Technically, No Snake Is Poisonous

Venomous Snakes in Pennsylvania The first question most people ask when they see a snake is “Is that snake poisonous?” Technically, no snake is poisonous. A plant or animal that is poisonous is toxic when eaten or absorbed through the skin. A snake’s venom is injected, so snakes are classified as venomous or nonvenomous. In Pennsylvania, we have only three species of venomous snakes. They all belong to the pit viper Nostril family. A snake that is a pit viper has a deep pit on each side of its head that it uses to detect the warmth of nearby prey. This helps the snake locate food, especially when hunting in the darkness of night. These Pit pits can be seen between the eyes and nostrils. In Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania Snakes all of our venomous Checklist snakes have slit-like A complete list of Pennsylvania’s pupils that are 21 species of snakes. similar to a cat’s eye. Venomous Nonvenomous Copperhead (venomous) Nonvenomous snakes Eastern Garter Snake have round pupils, like a human eye. Eastern Hognose Snake Eastern Massasauga (venomous) Venomous If you find a shedded snake Eastern Milk Snake skin, look at the scales on the Eastern Rat Snake underside. If they are in a single Eastern Ribbon Snake Eastern Smooth Earth Snake row all the way to the tip of its Eastern Worm Snake tail, it came from a venomous snake. Kirtland’s Snake If the scales split into a double row Mountain Earth Snake at the tail, the shedded skin is from a Northern Black Racer Nonvenomous nonvenomous snake. -

Veterans Park Herpetological Report Manning 2015

To Whom It May Concern, The information in this document is the summary of a series of volunteer reptile and amphibian observations conducted in Hamilton Veteran’s Park in Mercer County, NJ. The document has been prepared for the Township of Hamilton. The results presented are from field observations and data collected in 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015. The data from the first three years was taken informally during morning and evening walks with family. The data from 2015 was taken for a volunteer reptile and amphibian survey performed upon the request of the Township of Hamilton, Mercer County, NJ. This information is presented voluntarily for use in conservation endeavors. General Profile: Hamilton Veteran’s Park is a 350‐acre park managed by the Township of Hamilton in Mercer County, New Jersey. The park features a diversity of habitats within its boundaries, including a field which was the site of a former farm, a wetlands meadow, a smaller upland meadow, several patches of deciduous forest, a man‐made lake, temporary and permanent wetlands, an intermittent stream, and several permanent streams. The park is located on the physiographic province known as the inner coastal plain. Comments on General Fauna: The Veteran’s Park property provides a variety of habitats for native fauna to flourish. Healthy numbers of invertebrates have been observed during the survey. Checking under logs and other cover debris reveals a multitude of native decomposers, such as ants, earthworms, slugs, centipedes, harvestmen, and others. Ticks are occasionally seen in the fields, however most of those observed were dog ticks. -

WHO Guidance on Management of Snakebites

GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF SNAKEBITES 2nd Edition GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF SNAKEBITES 2nd Edition 1. 2. 3. 4. ISBN 978-92-9022- © World Health Organization 2016 2nd Edition All rights reserved. Requests for publications, or for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications, whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution, can be obtained from Publishing and Sales, World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia, Indraprastha Estate, Mahatma Gandhi Marg, New Delhi-110 002, India (fax: +91-11-23370197; e-mail: publications@ searo.who.int). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use. -

Effect of Ethanol on Thermoregulation in the Goldfish, Carassius Auratus

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1986 Effect of ethanol on thermoregulation in the goldfish, Carassius auratus Candace Sharon O'Connor Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Biology Commons, and the Physiology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation O'Connor, Candace Sharon, "Effect of ethanol on thermoregulation in the goldfish, Carassius auratus" (1986). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3703. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.5587 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS of Candace Sharon O'Connor for the Master of Science in Biology presented May 16, 1986. Title: Effect of Ethanol on Thermoregulation in the Goldfish, Carassius auratus. APPROVED BY MEMBERS OF THE TIIBSIS COMMITTEE: Leonard Simpson In an attempt to elucidate the mechanism by which ethanol affects vertebrate thermoregulation, the effect of ethanol on temperature selection was studied in the goldfish, Carassius auratus. Ethanol was administered to 10 to 15 g fish by mixing it in the water of a temperature gradient. The dose response curve was very steep between 0.5% (v/v) ethanol (no response) and 0.7% (significant lowering of selected temperature in treated fish). Fish were exposed to concentrations of ethanol as high as 1.7%, at which concentration most experimental fish lost their ability to swim upright in the water. -

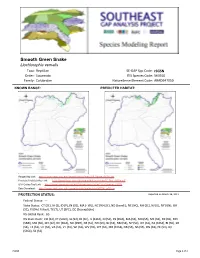

Smooth Green Snake

Smooth Green Snake Liochlorophis vernalis Taxa: Reptilian SE-GAP Spp Code: rSGSN Order: Squamata ITIS Species Code: 563910 Family: Colubridae NatureServe Element Code: ARADB47010 KNOWN RANGE: PREDICTED HABITAT: P:\Proj1\SEGap P:\Proj1\SEGap Range Map Link: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/maps/SE_Range_rSGSN.pdf Predicted Habitat Map Link: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/maps/SE_Dist_rSGSN.pdf GAP Online Tool Link: http://www.gapserve.ncsu.edu/segap/segap/index2.php?species=rSGSN Data Download: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/region/vert/rSGSN_se00.zip PROTECTION STATUS: Reported on March 14, 2011 Federal Status: --- State Status: CT (SC), IA (S), ID (P), IN (SE), MA (- WL), NC (W4,SC), ND (Level I), NE (NC), NH (SC), NJ (U), NY (GN), OH (SC), RI (Not Listed), TX (T), UT (SPC), QC (Susceptible) NS Global Rank: G5 NS State Rank: CO (S4), CT (S3S4), IA (S3), ID (SH), IL (S3S4), IN (S2), KS (SNA), MA (S5), MD (S5), ME (S5), MI (S5), MN (SNR), MO (SX), MT (S2), NC (SNA), ND (SNR), NE (S1), NH (S3), NJ (S3), NM (S4), NY (S4), OH (S4), PA (S3S4), RI (S5), SD (S4), TX (S1), UT (S2), VA (S3), VT (S3), WI (S4), WV (S5), WY (S2), MB (S3S4), NB (S5), NS (S5), ON (S4), PE (S3), QC (S3S4), SK (S3) rSGSN Page 1 of 4 SUMMARY OF PREDICTED HABITAT BY MANAGMENT AND GAP PROTECTION STATUS: US FWS US Forest Service Tenn. Valley Author. US DOD/ACOE ha % ha % ha % ha % Status 1 0.0 0 17.6 < 1 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 2 0.0 0 1,117.9 < 1 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 3 0.0 0 6,972.8 1 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 4 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Total 0.0 0 8,108.3 2 0.0 0 0.0 0 US Dept. -

Reptiles A. Cladistics 1. Many Groups of Organisms

Reptiles A. Cladistics 1. Many groups of organisms are “polyphyletic” a. This means that the group combines 2 or more lineages - example=fish 2. Cladistics follows only pure lineages going back in time - example Osteichthys B. Reptile Classifiecation - looks like a polyphyletic group 1. Dry skin - no loss of water through skin like amphibians 2. Aminotic egg - an egg that can survive on dry land - in contrast with the amphibian egg C. Mammals and Birds are derived from different lineages of reptiles (We will see below) D. Stem Reptiles 1. Different lineages based on the temporal region of their skulls - number of holes (or bars) a. These holes are necessary to accommodate large jaw muscles b. Anapsid Skull - no holes in temporal - jaws can move fast, but with little force 1. Muscles that move the jaw are small 2. There is no good paleotological evidence for the transition between amphibians and reptiles - no fossil intermediates a. Fossil amphibians have lots of dermal bones in skull b. Amphibians have no temporal openings in skull 1. (Aside) both fossil amphibians and primitive reptiles have a parietal “eye” that senses light and dark (“third” eye in middle of head) c. Reptile skull is higher than amphibian to accomodate larger jaw muscles d. Of the modern reptiles only turtles are anapsids 2. Diapsid Skull - has holes in the temporal region a. Diapsid reptiles gave rise to lizards and snakes - they have a diapsid skull 1. Also Tuatara, crocodiles, dinosaurs and pterydactyls Reptiles b. One group of diapsids also had a pre-orbital hole in the skull in front of eye - this hole is still preserved in the birds - this anatomy suggests strongly that the birds are derived from the diapsid reptiles 3. -

Serpent Symbols and Salvation in the Ancient Near East and the Book of Mormon

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 10 Number 2 Article 8 7-31-2001 Serpent Symbols and Salvation in the Ancient Near East and the Book of Mormon Andrew C. Skinner Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Skinner, Andrew C. (2001) "Serpent Symbols and Salvation in the Ancient Near East and the Book of Mormon," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 10 : No. 2 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol10/iss2/8 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Serpent Symbols and Salvation in the Ancient Near East and the Book of Mormon Author(s) Andrew C. Skinner Reference Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 10/2 (2001): 42–55, 70–71. ISSN 1065-9366 (print), 2168-3158 (online) Abstract The serpent is often used to represent one of two things: Christ or Satan. This article synthesizes evi- dence from Egypt, Mesopotamia, Phoenicia, Greece, and Jerusalem to explain the reason for this duality. Many scholars suggest that the symbol of the serpent was used anciently to represent Jesus Christ but that Satan distorted the symbol, thereby creating this para- dox. The dual nature of the serpent is incorporated into the Old Testament, the New Testament, and the Book of Mormon. erpent ymbols & SSalvation in the ancient near east and the book of mormon andrew c. -

Distribution of the Queen Snake (Regina Septemvittata) in Arkansas Johnathan W

Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science Volume 61 Article 17 2007 Distribution of the Queen Snake (Regina septemvittata) in Arkansas Johnathan W. Stanley Arkansas State University, [email protected] Stanley E. Trauth Arkansas State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas Part of the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Stanley, Johnathan W. and Trauth, Stanley E. (2007) "Distribution of the Queen Snake (Regina septemvittata) in Arkansas," Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science: Vol. 61 , Article 17. Available at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol61/iss1/17 This article is available for use under the Creative Commons license: Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-ND 4.0). Users are able to read, download, copy, print, distribute, search, link to the full texts of these articles, or use them for any other lawful purpose, without asking prior permission from the publisher or the author. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science, Vol. 61 [2007], Art. 17 -I Distribution of the Queen Snake (Regina septemvittata) in Arkansas llinOiS./ JONATHAN W. STANLEyl,2 AND STANLEY E. TRAUTH1 ~orgia. lDepartment ofBiological Sciences, Arkansas State University, PO Box 599, State University, AR 72467-0599 rabbi! NOods /. torrespondence: [email protected] I [MS , i ~rslty. I Abstract.-We documented the distribution ofthe queen snake, Regina septemvittata, in northern Arkansas during the 2005 and 2006 activity seasons. -

Ostrich Production Systems Part I: a Review

11111111111,- 1SSN 0254-6019 Ostrich production systems Food and Agriculture Organization of 111160mmi the United Natiorp str. ro ucti s ct1rns Part A review by Dr M.M. ,,hanawany International Consultant Part II Case studies by Dr John Dingle FAO Visiting Scientist Food and , Agriculture Organization of the ' United , Nations Ot,i1 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. M-21 ISBN 92-5-104300-0 Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders. Applications for such permission, with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction, should be addressed to the Director, Information Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Viale dells Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy. C) FAO 1999 Contents PART I - PRODUCTION SYSTEMS INTRODUCTION Chapter 1 ORIGIN AND EVOLUTION OF THE OSTRICH 5 Classification of the ostrich in the animal kingdom 5 Geographical distribution of ratites 8 Ostrich subspecies 10 The North -

Morphology, Phylogeny, and Evolution of Diadectidae (Cotylosauria: Diadectomorpha)

Morphology, Phylogeny, and Evolution of Diadectidae (Cotylosauria: Diadectomorpha) by Richard Kissel A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of doctor of philosophy Graduate Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology University of Toronto © Copyright by Richard Kissel 2010 Morphology, Phylogeny, and Evolution of Diadectidae (Cotylosauria: Diadectomorpha) Richard Kissel Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology University of Toronto 2010 Abstract Based on dental, cranial, and postcranial anatomy, members of the Permo-Carboniferous clade Diadectidae are generally regarded as the earliest tetrapods capable of processing high-fiber plant material; presented here is a review of diadectid morphology, phylogeny, taxonomy, and paleozoogeography. Phylogenetic analyses support the monophyly of Diadectidae within Diadectomorpha, the sister-group to Amniota, with Limnoscelis as the sister-taxon to Tseajaia + Diadectidae. Analysis of diadectid interrelationships of all known taxa for which adequate specimens and information are known—the first of its kind conducted—positions Ambedus pusillus as the sister-taxon to all other forms, with Diadectes sanmiguelensis, Orobates pabsti, Desmatodon hesperis, Diadectes absitus, and (Diadectes sideropelicus + Diadectes tenuitectes + Diasparactus zenos) representing progressively more derived taxa in a series of nested clades. In light of these results, it is recommended herein that the species Diadectes sanmiguelensis be referred to the new genus -

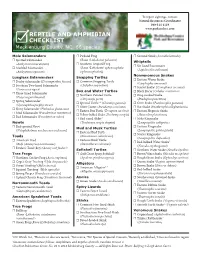

Checklist Reptile and Amphibian

To report sightings, contact: Natural Resources Coordinator 980-314-1119 www.parkandrec.com REPTILE AND AMPHIBIAN CHECKLIST Mecklenburg County, NC: 66 species Mole Salamanders ☐ Pickerel Frog ☐ Ground Skink (Scincella lateralis) ☐ Spotted Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) palustris) Whiptails (Ambystoma maculatum) ☐ Southern Leopard Frog ☐ Six-lined Racerunner ☐ Marbled Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) sphenocephala (Aspidoscelis sexlineata) (Ambystoma opacum) (sphenocephalus)) Nonvenomous Snakes Lungless Salamanders Snapping Turtles ☐ Eastern Worm Snake ☐ Dusky Salamander (Desmognathus fuscus) ☐ Common Snapping Turtle (Carphophis amoenus) ☐ Southern Two-lined Salamander (Chelydra serpentina) ☐ Scarlet Snake1 (Cemophora coccinea) (Eurycea cirrigera) Box and Water Turtles ☐ Black Racer (Coluber constrictor) ☐ Three-lined Salamander ☐ Northern Painted Turtle ☐ Ring-necked Snake (Eurycea guttolineata) (Chrysemys picta) (Diadophis punctatus) ☐ Spring Salamander ☐ Spotted Turtle2, 6 (Clemmys guttata) ☐ Corn Snake (Pantherophis guttatus) (Gyrinophilus porphyriticus) ☐ River Cooter (Pseudemys concinna) ☐ Rat Snake (Pantherophis alleghaniensis) ☐ Slimy Salamander (Plethodon glutinosus) ☐ Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina) ☐ Eastern Hognose Snake ☐ Mud Salamander (Pseudotriton montanus) ☐ Yellow-bellied Slider (Trachemys scripta) (Heterodon platirhinos) ☐ Red Salamander (Pseudotriton ruber) ☐ Red-eared Slider3 ☐ Mole Kingsnake Newts (Trachemys scripta elegans) (Lampropeltis calligaster) ☐ Red-spotted Newt Mud and Musk Turtles ☐ Eastern Kingsnake