The Strategy and Translation Challenges Behind Proverb and Idiom Twisting in NCIS Damien Villers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

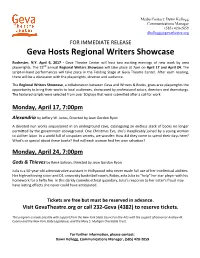

Geva Hosts Regional Writers Showcase

Media Contact: Dawn Kellogg Communications Manager (585) 420-2059 [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Geva Hosts Regional Writers Showcase Rochester, N.Y. April 6, 2017 - Geva Theatre Center will host two exciting evenings of new work by area playwrights. The 22nd annual Regional Writers Showcase will take place at 7pm on April 17 and April 24. The script-in-hand performances will take place in the Fielding Stage at Geva Theatre Center. After each reading, there will be a discussion with the playwrights, director and audience. The Regional Writers Showcase, a collaboration between Geva and Writers & Books, gives area playwrights the opportunity to bring their works to local audiences, showcased by professional actors, directors and dramaturgs. The featured scripts were selected from over 50 plays that were submitted after a call for work. Monday, April 17, 7:00pm Alexandria by Jeffery W. Jones, Directed by Jean Gordon Ryon A devoted nun works sequestered in an underground cave, cataloguing an endless stack of books no longer permitted by the government aboveground. One Christmas Eve, she’s inexplicably joined by a young woman to aid her labor. In a world full of unspoken secrets, we wonder: How did they come to spend their days here? What’s so special about these books? And will each woman find her own salvation? Monday, April 24, 7:00pm Gods & Thieves by René Solivan, Directed by Jean Gordon Ryon Julia is a 50-year-old administrative assistant in Hollywood who never made full use of her intellectual abilities. Her high-achieving sister and D1 university basketball coach, Robin, asks Julia to “help” her star player with his homework for a hefty fee. -

Girl Power Margulies Star in “Dietland” Mon.-Fri

FINAL-1 Sat, Jun 23, 2018 5:15:18 PM Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment for the week of June 30 - July 6, 2018 HARTNETT’S ALL SOFT CLOTH CAR WASH $ 00 OFF 3ANY CAR WASH! EXPIRES 7/31/18 BUMPER SPECIALISTSHartnett's Car Wash H1artnett x 5` Auto Body, Inc. COLLISION REPAIR SPECIALISTS & APPRAISERS MA R.S. #2313 R. ALAN HARTNETT LIC. #2037 DANA F. HARTNETT LIC. #9482 15 WATER STREET DANVERS (Exit 23, Rte. 128) TEL. (978) 774-2474 FAX (978) 750-4663 Joy Nash and Julianna Open 7 Days Girl power Margulies star in “Dietland” Mon.-Fri. 8-7, Sat. 8-6, Sun. 8-4 ** Gift Certificates Available ** Choosing the right OLD FASHIONED SERVICE Attorney is no accident FREE REGISTRY SERVICE Free Consultation PERSONAL INJURYCLAIMS • Automobile Accident Victims • Work Accidents • Slip &Fall • Motorcycle &Pedestrian Accidents John Doyle Forlizzi• Wrongfu Lawl Death Office INSURANCEDoyle Insurance AGENCY • Dog Attacks • Injuries2 x to 3 Children Voted #1 1 x 3 With 35 years experience on the North Insurance Shore we have aproven record of recovery Agency No Fee Unless Successful Plum (Joy Nash, “Twin Peaks: The Return”) struggles to come to terms with the truth The LawOffice of about who she really is in a new episode of “Dietland,” airing Monday, July 2, on AMC. STEPHEN M. FORLIZZI Based on the acclaimed novel of the same name, the freshman series follows an over- Auto • Homeowners weight magazine writer who becomes entangled in a feminist revolution. Julianna 978.739.4898 Business • Life Insurance Harthorne Office Park •Suite 106 www.ForlizziLaw.com Margulies (“The Good Wife”) co-stars as Plum’s boss, ambitious magazine editor Kitty 978-777-6344 491 Maple Street, Danvers, MA 01923 [email protected] Montgomery. -

May 2009 $.25 Captured by Pirates!

May 2009 $.25 School News p. 3 National News p. 1,3 Captured By Pirates! By Hannah Williams Students of Month p. 5-8 8th Grade Profile p. 4 On the night of April 8, 2009, Captain Richard Phillips’ Top Ten List p. 1 cargo ship, the Maersk Alabama, was attacked by four pirates in Mystery Teacher p. 4 the northwestern area of the The Question p. 2 Indian Ocean. Piracy has been a problem off the coast of Somalia Movie Review p. 2 since the beginning of Somalia’s civil war in the 1990’s. Top Ten Roller Coasters Advice p. 3 Phillips saw first By Alexa Johnson TV Show Review p. 4 hand how brutal piracy can be. He was taken as a hostage and 10. Superman - Ride of In Ten Years.... p. 9 - 14 calls the whole ordeal, “surreal”. Steel (NY) Although the 19 crew members 9. Son of Beast and himself were very prepared for a pirate attack, the four pirates 8. Goliath ended up getting Phillips alone in 7. Urchen Five the emergency lifeboat. Two days 6. Superman–The Escape after he was captured, Phillips 5. Oblivion made an escape attempt by 4. The Beast pushing one of his captors aside, 3. Superman – Ride of and simply jumping overboard. As he was trying to swim to Steel (New England) safety, his attempt was foiled by 2. Top Thrill Dragster one of the pirates shooting at him. and the number one He just decided to swim back to roller coaster is the boat. 1. Millenium Force Then, finally on April 12, the US Navy destroyer, the USS Bainbridge, launched a rescue operation authorized by the president. -

Alumni Relations Provides a Vehicle to Further Engage Graduates Who Have a Vested Interest in Our Local Schools

▌INVOLVEMENT Broadening Community-Based Support Alumni Relations provides a vehicle to further engage graduates who have a vested interest in our local schools. It allows us to utilize successful graduates as role models and provides a venue for alumni to build relationships with other classmates. Behind every great Miamian there’s a teacher. Senator Bob Graham (Miami Senior High, Class of 1955) salutes his most inspiring teacher, Lamar Louise Curry Miami-Dade County Public Schools alumni.dadeschools.net Miami-Dade County Public Schools Alumni Hall of Fame Inaugural Inductees A panel of community leaders met May 11, 2011 to select the first inductees into the District’s new Alumni Hall of Fame. The panel chose by consensus the following alumni in established categories: Arts & Entertainment Andy Garcia Actor Miami Beach Senior High School (Class of 1974) Nautilus Junior High School Biscayne Elementary School Business Jeffrey Preston Bezos Founder & CEO, Amazon.com Miami Palmetto Senior High School (Class of 1982) Public Service Bob Graham Former Florida Governor Former U.S. Senator Miami Senior High School Science, Technology, Engineering & Math Wendy Chung, M.D., Ph.D. Molecular Geneticist Assistant Professor for Pediatrics, Columbia University Medical Center Westinghouse Science Prize Winner Miami Killian Senior High School (Class of 1986) Glades Middle School Kenwood Elementary School Sports Andre Dawson Major League Baseball Hall of Famer Southwest Miami Senior High School (Class of 1972) South Miami Junior High School Singular Achievement Dr. Dorothy Jenkins Fields Historian, Preservationist, retired M-DCPS Librarian Booker T. Washington High School (Class of 1960) Phillis Wheatley Elementary School Miami-Dade County Public Schools Alumni Hall of Fame Inaugural Inductees In addition to naming an inductee in each established category, the panel also chose to award a special citation to the four M-DCPS alumni who have flown in space as U.S. -

Once a Hero Free Download

ONCE A HERO FREE DOWNLOAD Elizabeth Moon | 416 pages | 01 Apr 1998 | Baen Books | 9780671878719 | English | Riverdale, United States Once a Hero Cote de Pablo. The Evolution of Armie Hammer. She and Barin begin going to psychiatric care. It's amazing. Not to mention state troopers, metro cops and NCIS' finest Photos Add Image. The main focus is on dedicated women, courageous and competent. It's even better when it's obvious that the author knows his or her science but DOES NOT ram it down our throats in the form of pages and pages of science lectures and ''l I enjoy a good SciFi Once a Hero especially one that features a woman who is strong and can take things in stride, learning along the way, etc. Also crossing over is a detective character called Gumshoe Robert Forsterwho's looking out for Justice. Episodes Seasons. This book has it all! Runtime: 60 min 5 episodes. Was this review helpful to you? Kirk speaks to Spock in preparing the eulogy. I did enjoy the story for the story's sake. Add to Wishlist. Sign In. Esmay is a great character, and I thoroughly enjoyed most of this book. Uh-oh, it looks like your Internet Explorer is out of date. Ducky says that the girl recently came from China. Rape was involved, but not described in Once a Hero. I'm looking forward to reading the next book in the series. I love, love, love this book. She transfers to "command track" and becomes intimate with Barin. I thought it worked quite well; there's not a lot of genre innovation here, so it's all about how Moon chooses to put the well-known pieces together. -

NCIS Star Cote De Pablo Loves Her Boyfriend for Being a Bad Influence

NCIS Star Cote de Pablo Loves Her Boyfriend for Being a Bad Influence NCIS actress Cote de Pablo loves her boyfriend, despite their opposite personalities, according to People. “I’m in a long-term relationship with [actor] Diego Serrano, and I’m very happy,” said the actress. “He’s the worst influence that I have ever had in my life, and I love him for it.” De Pablo, 31, elaborated, saying, “Every once in a while, he turns to me and goes, ‘Live a little.’ I’ll have chicken with broccoli and he’s like, ‘What about the chocolate cake?’ If it weren’t for him, I’d be the most boring person in Los Angeles…we balance each other.” What are the benefits of having the opposite personality of your partner? Cupid’s Advice: While many feel that two people need to have similar personalities in order to make a relationship work, the old cliché “opposites attract” does have some merit. Here are some reasons: 1. It’s exciting: While it’s possible to have fun with a partner who has the same interests as you, true thrill often springs from the excitement you get from stepping out of your comfort zone. 2. You can learn new things: If you like shopping and your partner enjoys hiking, then the two of you can learn a lot from each other. You may discover a love of nature and your partner may begin to appreciate the indoors. You can encourage each other to be open-minded. 3. You become well-rounded: By dating people different than yourself, you gain more points of view and life experience than you would gain by staying only with what you already know.. -

E-Score Celebrity Special Report Data Through Third Quarter 2009

E-Score Celebrity Special Report Data through Third Quarter 2009 Prepared for: E-Score Celebrity Clients www.epollresearch.com - 877-MY E-POLL Market Research Table of Contents E-Score Celebrity Methodology……………………………………………….….……..3 Celebrities with Highest Appeal By Age Group………...……………………………..….4 Celebrities with Biggest Gains and Declines in Appeal…………………………………..7 Up & Comers – Low Awareness, High Appeal, and Talented.………….………………..10 Blockbuster Movie Actor/Actress Gains and Declines By Age Group.…………………....12 Most Appealing Reality TV Show Host By Age Group……………………...……………..14 About E-Score Celebrity & E-Poll Market Research …………..……………………...….17 Contact Information………………………………………………………………...…..20 2 www.epollresearch.com - 877-MY EPOLL Market Research E-Score Celebrity: Methodology The E-Score Celebrity database includes more than 4,800 celebrities, athletes, and newsmakers Methodology • E-Poll panel members receive survey invitations via email • Respondents age 13+, total completed surveys per wave = 1,100 • Stratified sample - representative of the general population by age, gender, region • Unique sample, fielded on a weekly basis • Length of survey limited to 25 names • Name only / Image only evaluation of awareness • Six point appeal scale • More than 40 attributes + open ends Please Note: Throughout this report… • Only celebrities with at least 16% awareness are referenced, except in the case of the “Up and Comers” list which includes celebrities with awareness between 6% and 15% and the “Blockbuster Movie Actor/Actress -

The Glam Squad: Profiles of CSI's Lauren Lee Smith

PhotograPhy by Cliff liPson • styling by angelique o’neil CBS’ MOST STUNNING CRIME FIGHTERS— LAUREN LEE SMITH OF CSI, COTE DE PAblO OF NCIS AND EVA LA RUE OF CSI: MIAmi— TRADE THEIR BADGES FOR A DAY IN THE CALIFORNIA SUN. by Jim ColuCCi They hunt down stray hairs and other crime scene clues. They dissect dead bodies. Sometimes, they even rough up rogue gunmen. And all the while, they look darn good. These are the lady crime fighters of CBS. With beauty as their special weapon, Cote de Pablo, lauren lee smith and eva la rue can stun any adversary into submission—and us viewers as well. At our photo shoot in Laguna Beach, Calif., Watch! asked these stars from NCIS, CSI and CSI: Miami, respectively, to trade in their firearms for mascara wands.e ffectively disarmed, the three sirens of the small screen revealed the secrets behind their pulchritudinous power. GLAM 42 June 2009 Watch! FdCW0609_42-53_Glam Squad.indd 42 4/7/09 2:44:55 PMSQUAD GLAM SQUFdCW0609_42-53_Glam Squad.indd 43 AD4/7/09 11:36:15 AM 44 June 2009 Watch! FdCW0609_42-53_Glam Squad.indd 44 4/7/09 11:37:44 AM CSI AIRS THURSDAYS AT 9 P.M. ET/PT ON CBS. LAUREN LEE SMITH or Lauren Lee Smith, the with each role, the chameleon-like actress fresh-faced actress behind has sported a different look. “For every major CSI’s newest investigator project, I try to change as much as possible. Riley Adams, a high-style I’m surprised that I actually have hair on my photo shoot can be a welcome head right now, because it’s been every color change. -

2011 NLMC Network Diversity Narrative

NLMC National Latino Media Council 2011 NLMC Network Diversity Narrative Two years ago the National Latino Media Council (NLMC) celebrated the 10th anniversary of the signing of the historic Memoranda of Understanding between the Multi-Ethnic Media Coalition1 and the top television broadcast networks: ABC, NBC, CBS and FOX. This is the 10th anniversary of the Diversity Report Cards. This ten year partnership has produced tangible and incremental results, but we seem to have reached a plateau. The networks want to reach the burgeoning Latino audience, but they have yet to understand just how to do so. According to the 2010 Census, Latinos are 16% of the U.S. population, representing $1 trillion in purchasing power annually. During the 2009-2010 television season, the Nielsen Company identified 12.9 million U.S. Latino TV households; approximately 65% of these households watch English media. As the Latino population continues to grow, the networks’ diversity performance remains inadequate. In the next decade, NLMC will identify and encourage the systematic change needed to weave more Latinos into the networks’ fabric. The network executives understand that Latinos represent a considerable audience, yet they struggle to create shows with which Latinos can connect. NLMC grades the networks on creative executives because it is essential that Latinos be part of the decision-making teams that green light programs. Without more Latinos creative executives, writers, producers and directors, television shows are less likely to succeed in attracting the Latino audience. There is much work to be done in the area of adding diversity to the ranks of working writers in Hollywood. -

Entertainment &

CALENDAR DININGPUZZLES ENTERTAINMENT & www.southernheatingandac.biz/ March 27 - April 2, 2020 TV $10.00 OFF any service call one per customer. 910-738-70002105-A EAST ELIZABETHTOWN RD THE ROBESONIAN CARDINAL HEART AND VASCULAR PLLC Suriya Jayawardena MD. FACC. FSCAI Boards Certified Physician Heart Disease, Leg Pain due to poor circulation, Varicose Veins, Obesity, Erectile Dysfunction and Allergy clinic. All insurances accepted. Same week appointments. Friendly Staff. Testing done in the same office. Plan for Healthy Life Style 4380 Fayetteville Rd. • Lumberton, NC 28358 Tele: 919-718-0414 • Fax: 919-718-0280 • Hours of Operation: 8am-5pm Monday-Friday 2 Entertainment • TV Friday, March 27, 2020 | Robesonian Page 2 — Saturday, March 28, 2020 — The Robesonian Special delivery: PBS presents the ninth season of ‘Call the Midwife’ By Rachel Jones natus house team up to serve local ness and steady hand have helped It’s no secret that the “Call the galized abortion by licensed practi- and the sometimes fraught doctor- TV Media families in the fictional area of many of the sisters, midwives and Midwife” series has effects that tioners in certain areas of the U.K. in nurse relationship. Could there be a Poplar, London. townspeople through difficult reach far beyond entertainment. The the hopes of ending the dangerous, chance for romance as well? BS’s hit series “Call the Mid- Among the team of midwives is times. characters’ positive perspectives and often fatal, back-alley proce- The first episode of the new sea- Pwife” reminds us that there is a the newly sober Trixie Franklin The show is based on the Mid- and empathetic attitudes have dures that were common before son features a diphtheria outbreak time to be born, a time to die and a (Helen George, “The Three Muske- wife Trilogy, a memoir collection shined a light on female struggles that time. -

Florida Legislature Approves Budget, Ends Annual Session

EUSTIS SOFTBALL FALLS IN REGIONAL FINAL, SPORTS B1 LEESBURG, FLORIDA Sunday, May 4, 2014 www.dailycommercial.com GROVELAND: New city manager wants more OKLAHOMA: Lawmakers say they great ideas from residents, employees, A3 won’t abandon death penalty, A6 State budget includes goodies for local programs LIVI STANFORD | Staff Writer from the state bud- [email protected] get, which will aid pro- grams in the commu- The Florida Legisla- nity. ture passed a $77 bil- Lake Technical Col- lion budget Friday that includes $3 mil- lege, Lifestream Be- lion for construction havioral Center and of a new science lab at the South Lake Re- the Lake-Sumter State gional Water Initiative College South Lake also will receive fund- Campus to jump start ing. a magnet school for But the magnet the highest perform- school is one of the ing students in south largest projects in the Lake. county. Lake-Sumter State “It is going to be a College, South Lake real benefit for our Hospital, the Lake community and all the County School District students in the mag- STEVE CANNON / AP and University of Cen- net program and those Senate president Don Gaetz, R-Niceville, talks with house speaker Will Weatherford on the phone as he prepares to bang tral Florida have come students in dual en- the gavel to end the session on Friday in Tallahassee. together and will give rollment,” Lake Coun- final approval in the ty School Board Vice coming weeks to the Chairman Tod Howard school. It would serve said. “It is going to be a Florida Legislature approves 100 high-performing part of the future eco- students in the ninth nomic development grade, who would take for south Lake Coun- budget, ends annual session two years of advanced ty.” placement classes, fol- Sasheika Tomlinson, director of marking GARY FINEOUT aimed at overhauling lowed by dual-enroll- Associated Press the child-welfare sys- ment at LSSC and two and college relations years at the University for the LSSC, said the lush with cash, tem. -

Sydney Program Guide

Firefox http://prtten04.networkten.com.au:7778/pls/DWHPROD/Program_Repor... SYDNEY PROGRAM GUIDE Sunday 29th August 2021 06:00 am Home Shopping (Rpt) Home Shopping 06:30 am Home Shopping (Rpt) Home Shopping 07:00 am Home Shopping (Rpt) Home Shopping 07:30 am Key Of David PG The Key of David, a religious program, covers important issues of today with a unique perspective. 08:00 am Bondi Rescue (Rpt) CC PG WS Bondi Rescue follows the work of elite lifeguards in charge at the world's busiest beach. With people's lives literally in their hands, these lifeguards ensure safety is their number one priority. 08:30 am Reel Action (Rpt) CC G Mountain Trout Fishing takes you to some amazingly diverse locations. Guesty and Jack Nolan wet a line with the “Trout Father” Paul Sheather near Ebor casting lures for energetic rainbow trout. 09:00 am Snap Happy (Rpt) CC G If you like photography then you'll love Snap Happy. This show will inspire and equip you to become a better photographer. 09:30 am Escape Fishing With ET (Rpt) CC PG Escape with former Rugby League Legend "ET" Andrew Ettingshausen as he travels Australia and the Pacific, hunting out all types of species of fish, while sharing his knowledge on how to catch them. 10:00 am Roads Less Travelled (Rpt) CC An Australian Road Trip Series exploring those hidden gems that only the locals know about. Tour some of the lesser known roads exploring unique locations amidst Australia's natural beauty. 10:30 am Bondi Rescue (Rpt) CC PG WS Sexual References, Bondi Rescue follows the work of elite lifeguards in charge at the world's Mild Coarse Language busiest beach.