Outside the Lines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yankee Stadium and the Politics of New York

The Diamond in the Bronx: Yankee Stadium and The Politics of New York NEIL J. SULLIVAN OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS THE DIAMOND IN THE BRONX This page intentionally left blank THE DIAMOND IN THE BRONX yankee stadium and the politics of new york N EIL J. SULLIVAN 1 3 Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paolo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Copyright © 2001 by Oxford University Press Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available. ISBN 0-19-512360-3 135798642 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper For Carol Murray and In loving memory of Tom Murray This page intentionally left blank Contents acknowledgments ix introduction xi 1 opening day 1 2 tammany baseball 11 3 the crowd 35 4 the ruppert era 57 5 selling the stadium 77 6 the race factor 97 7 cbs and the stadium deal 117 8 the city and its stadium 145 9 the stadium game in new york 163 10 stadium welfare, politics, 179 and the public interest notes 199 index 213 This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgments This idea for this book was the product of countless conversations about baseball and politics with many friends over many years. -

Christy Mathewson Was a Great Pitcher, a Great Competitor and a Great Soul

“Christy Mathewson was a great pitcher, a great competitor and a great soul. Both in spirit and in inspiration he was greater than his game. For he was something more than a great pitcher. He was The West Ranch High School Baseball and Theatre Programs one of those rare characters who appealed to millions through a in association with The Mathewson Foundation magnetic personality attached to clean honesty and undying loyalty present to a cause.” — Grantland Rice, sportswriter and friend “We need real heroes, heroes of the heart that we can emulate. Eddie Frierson We need the heroes in ourselves. I believe that is what this show you’ve come to see is all about. In Christy Mathewson’s words, in “Give your friends names they can live up to. Throw your BEST pitches in the ‘pinch.’ Be humble, and gentle, and kind.” Matty is a much-needed force today, and I believe we are lucky to have had him. I hope you will want to come back. I do. And I continue to reap the spirit of Christy Mathewson.” “MATTY” — Kerrigan Mahan, Director of “MATTY” “A lively visit with a fascinating man ... A perfect pitch! Pure virtuosity!” — Clive Barnes, NEW YORK POST “A magnificent trip back in time!” — Keith Olbermann, FOX SPORTS “You’ll be amazed at Matty, his contemporaries, and the dramatic baseball events of their time.” — Bob Costas, NBC SPORTS “One of the year’s ten best plays!” — NATIONAL PUBLIC RADIO “Catches the spirit of the times -- which includes, of course, the present -- with great spirit and theatricality!” -– Ira Berkow, NEW YORK TIMES “Remarkable! This show is as memorable as an exciting World Series game and it wakes up the echoes about why we love An Evening With Christy Mathewson baseball. -

Oklahoma Redhawks (W-L Record: 74-70)

At El SEATTLE MARINERS MINOR LEAGUE REPORT Games of August 31, 2018 5 YESTERDAY’S RESULT CURRENT FIRST HALF OVERALL WINNER/LOSER/SAVE at El Paso 7, Tacoma 6 64-72, 3rd, -16.0 --- --- L-Higgins (1-1) Arkansas 5, at Springfield 3 35-31, 2nd, -2.0 35-35, T1st, +1.0* 70-66, 2nd, -1.0 W-Walker (5-1)/S-Festa (20) Modesto 3, at San Jose 1 31-36, T2nd, -1.0 30-40, 4th, -14.0 61-76, 3rd, -15.0 W-Boches (1-0)/S-Kober (2) Quad Cities 6, at Clinton 1 28-39, 7th, -16.0 39-31, T2nd, -1.0 67-70, 6th, -11.0 L-Moyers (4-2) Everett 9, at Vancouver 3 15-19, 4th, -4.5 20-18, 1st, +0.5* 35-37, 3rd, -4.5 W-Brown (2-4) AZL Mariners 8-19, 5th, -11.0 8-19, 6th, -9.5 16-38, 6th, -20.5 END OF SEASON DSL Mariners 40-32, 2nd, -13.0 --- --- END OF SEASON CURRENT LEAGUE STANDINGS Pacific Coast League Standings (Northern Division): Northwest League Standings (Northern Division): W L PCT GB Home Away Div Streak L10 W L PCT GB Home Away Div Streak L10 Fresno Grizzlies 80 56 .588 - 41-28 39-28 26-22 W2 8-2 Spokane Indians 20 15 .571 - 11-5 9-10 9-6 W2 7-3 Reno Aces 69 68 .504 11.5 37-30 32-38 23-25 L1 3-7 Vancouver Canadians 20 15 .571 - 11-8 9-7 6-9 L2 5-5 Tacoma Rainiers 64 72 .471 16.0 34-36 30-36 24-24 L6 3-7 Tri-City Dust Devils 16 18 .471 3.5 7-11 9-7 7-7 L2 5-5 Sacramento River Cats 54 83 .394 26.5 27-43 27-40 23-25 L2 4-6 Everett AquaSox 15 19 .441 4.5 9-7 6-12 7-7 W2 4-6 Texas League Standings (North Division): Arizona League Standings (Western Division): W L PCT GB Home Away Div Streak L10 W L PCT GB Home Away Div Streak L10 Tulsa Drillers 37 29 .561 - 23-14 -

Chicago Tribune: Baseball World Lauds Jerome

Baseball world lauds Jerome Holtzman -- chicagotribune.com Page 1 of 3 www.chicagotribune.com/sports/chi-22-holtzman-baseballjul22,0,5941045.story chicagotribune.com Baseball world lauds Jerome Holtzman Ex-players, managers, officials laud Holtzman By Dave van Dyck Chicago Tribune reporter July 22, 2008 Chicago lost its most celebrated chronicler of the national pastime with the passing of Jerome Holtzman, and all of baseball lost an icon who so graciously linked its generations. Holtzman, the former Tribune and Sun-Times writer and later MLB's official historian, indeed belonged to the entire baseball world. He seemed to know everyone in the game while simultaneously knowing everything about the game. Praise poured in from around the country for the Hall of Famer, from management and union, managers and players. "Those of us who knew him and worked with him will always remember his good humor, his fairness and his love for baseball," Commissioner Bud Selig said. "He was a very good friend of mine throughout my career in the game and I will miss his friendship and counsel. I extend my deepest sympathies to his wife, Marilyn, to his children and to his many friends." The men who sat across from Selig during labor negotiations—a fairly new wrinkle in the game that Holtzman became an expert at covering—remembered him just as fondly. "I saw Jerry at Cooperstown a few years ago and we talked old times well into the night," said Marvin Miller, the first executive director of the Players Association. "We always had a good relationship. He was a careful writer and, covering a subject matter he was not familiar with, he did a remarkably good job." "You don't develop the reputation he had by accident," said present-day union boss Donald Fehr. -

Post-Game Notes

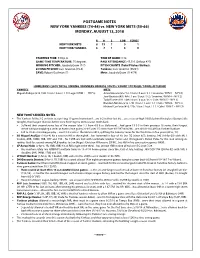

POSTGAME NOTES NEW YORK YANKEES (74-44) vs. NEW YORK METS (50-66) MONDAY, AUGUST 13, 2018 R H E LOB SERIES NEW YORK METS 8 15 1 9 1 NEW YORK YANKEES 5 7 1 5 0 STARTING TIME: 7:09 p.m. TIME OF GAME: 3:18 GAME-TIME TEMPERATURE: 75 degrees PAID ATTENDANCE: 47,233 (Sellout #22) WINNING PITCHER: Jacob deGrom (7-7) PITCH COUNTS (Total Pitches/Strikes): LOSING PITCHER: Luis Severino (15-6) Yankees: Luis Severino (98/64) SAVE: Robert Gsellman (7) Mets: Jacob deGrom (114/79) HOME RUNS (2018 TOTAL / INNING / RUNNERS ON BASE / OUTS / COUNT / PITCHER / SCORE AFTER HR) YANKEES METS Miguel Andújar (#18 / 8th / 2 on / 2 out / 1-0 / Lugo / NYM 7 – NYY 5) Amed Rosario (#5 / 1st / 0 on / 0 out / 3-1 / Severino / NYM 1 – NYY 0) José Bautista (#9 / 4th / 1 on / 0 out / 3-2 / Severino / NYM 4 – NYY 2) Todd Frazier (#11 / 6th / 0 on / 0 out / 0-2 / Cole / NYM 5 – NYY 3) Brandon Nimmo (#15 / 7th / 0 on / 1 out / 1-1 / Cole / NYM 6 – NYY 3) Michael Conforto (#16 / 7th / 0 on / 1 out / 1-1 / Cole / NYM 7 – NYY 3) NEW YORK YANKEES NOTES • The Yankees fell to 3-2 on their season-long 11-game homestand…are 6-2 in their last 8G…are a season-high 10.0G behind first-place Boston (idle tonight), their largest division deficit since finishing the 2016 season 10.0G back. • Suffered their second series loss of the season (also 1-3 from 4/5-8 vs. -

Weller Credits 2019

Production Design and Art Direction United Scenic Artists, Local 829 IATSE 505 Court Street 7P, Brooklyn NY 11231 NYC 212 9797761 Los Angeles 310 3981982 [email protected] IMDB: http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0919860/ LINKEDIN: www.linkedin.com/in/wellerdesign www.wellerdesign.com Production Design and Art Direction for film, television and theater. Extensive experience in single and multi camera art direction for features and network/cable television. Skillful, meticulous budgeting combined with quick and accurate drafting. Expertise in assembling and managing crews. Multiple Emmy Awards. Series NEW AMSTERDAM – Network Series - NBC UNIVERSAL 2019 Art Director ARMISTEAD MAUPIN’S TALES OF THE CITY – Mini Series- NETFLIX 2019 Assistant Art Director FIRST WIVE’S CLUB – PARAMOUNT NETWORK 2018 Art Director JESSICA JONES SEASON 3 - MARVEL PRODUCTIONS - NETFLIX 2018 Assistant Art Director JULIE’S GREENROOM – JIM HENSON PRODUCTIONS - NETFLIX –2016 Art Director QUANTICO – ABC - 2016 Assistant Art Director Feature Film LOST GIRLS – NETFLIX 2018 Art Director THE COMMUTER – LIONSGATE -2017 Assistant Art Director BRAWL IN CEL BLOCK 99 - RLJE FILMS - 2017 Art Department THE PERFECT GENTLEMAN – SHORT - 2010 Production Design BAD LIEUTENANT –ARIES FILMS -1992 Set Designer THE RAPTURE - FINE LINE FEATURES - 1991 Set Designer THE BLOODHOUNDS OF BROADWAY – COLUMBIA PICTURES - 1989 Assistant Art Director Live Events THE NEW LEVANT - KENNEDY CENTER 2018 GLAMOUR WOMEN OF THE YEAR- CONDE NAST Carnegie Hall 2016, 2017 ALICIA KEYS FOR VEUVE CLIQUOT – Liberty -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

Giving Back to the Base

SATURDAY,AUG. 12, 2017 Inside: 75¢ Experts: Eclipse maps inaccurate. — Page 4B Vol. 89 ◆ No. 115 SERVING CLOVIS, PORTALES AND THE SURROUNDING COMMUNITIES EasternNewMexicoNews.com Giving back to the base ❏ Cannon Appreciation 27th (Special Operations Wing),” Cannon Appreciation Day, said the said Clovis/Curry County Chamber Chamber’s Executive Director Day includes picnic, of Commerce President David Ernie Kos. The event hasn’t Robinson. “Clovis and Cannon changed much in that time, she raffle at base park. have always been close, and Clovis said, noting there’s, “no reason to likes it that way.” mess with a good thing.” By David Grieder Robinson spoke to a crowd of Air “It just gives us an opportunity to STAFF WRITER Force families sprawled across let (Cannon community members) [email protected] Cannon’s Unity Park, standing know how much we appreciate before a wall of raffle prizes award- them,” she said. “For them, it’s an CANNON AIR FORCE BASE ed during the afternoon shindig. opportunity to come out and have — Community leaders of Clovis “I’m thrilled,” said John Gaylord, an end-of-summer picnic.” and Curry County came together brandishing a vacuum cleaner he The Friday festivities were also Friday to host a picnic in the park received from the heap of $4,000 in hosted by the Chamber’s military- Staff photo: Tony Bullocks for the airmen, families and civilian prizes. “I don’t ever win these affairs specific “Committee of personnel of Cannon AFB. things.” City Commissioner Helen Casaus serves up food Friday during “Clovis is not Clovis without the This marks the 30th year of CANNON on Page 5A Cannon Appreciation Day at the base’s Unity Park. -

At NEW YORK METS (27-33) Standing in AL East

OFFICIAL GAME INFORMATION YANKEE STADIUM • ONE EAST 161ST STREET • BRONX, NY 10451 PHONE: (718) 579-4460 • E-MAIL: [email protected] • SOCIAL MEDIA: @YankeesPR & @LosYankeesPR WORLD SERIES CHAMPIONS: 1923, ’27-28, ’32, ’36-39, ’41, ’43, ’47, ’49-53, ’56, ’58, ’61-62, ’77-78, ’96, ’98-2000, ’09 YANKEES BY THE NUMBERS NOTE 2018 (2017) NEW YORK YANKEES (41-18) at NEW YORK METS (27-33) Standing in AL East: ............1st, +0.5 RHP Domingo Germán (0-4, 5.44) vs. LHP Steven Matz (2-4, 3.42) Current Streak: ...................Won 3 Current Road Trip: ................... 6-1 Saturday, June 9, 2018 • Citi Field • 7:15 p.m. ET Recent Homestand: ................. 4-2 Home Record: ..............22-9 (51-30) Game #61 • Road Game #30 • TV: FOX • Radio: WFAN 660AM/101.9FM (English), WADO 1280AM (Spanish) Road Record: ...............19-9 (40-41) Day Record: ................16-4 (34-27) Night Record: .............24-14 (57-44) AT A GLANCE: Tonight the Yankees play the second game of HOPE WEEK 2018 (June 11-15): This Pre-All-Star ................41-18 (45-41) their three-game Subway Series at the Mets (1-0 so far)…are 6-1 year marks the 10th annual HOPE Week Post-All-Star ..................0-0 (46-30) on their now-nine-game, four-city road trip, which began with a (Helping Others Persevere & Excel), vs. AL East: .................15-9 (44-32) rain-shortened two-game series in Baltimore (postponements an initiative rooted in the belief that vs. AL Central: ..............11-2 (18-15) on 5/31 and 6/3), a split doubleheader in Detroit on Monday acts of good will provide hope and vs. -

Boston Druggists' Association

BOSTON DRUGGISTS’ ASSOCIATION SPEAKERS, 1966 to 2019 Date Speaker Title/Topic February 15, 1966 The Honorable John A. Volpe Governor of Massachusetts March 22, 1966 William H. Sullivan, Jr. President, Boston Patriots January 24, 1967 Richard E. McLaughlin Registry of Motor Vehicles March 21, 1967 Hal Goodnough New York Mets Baseball February 27, 1968 Richard M. Callahan “FDA in Boston” January 30, 1968 The Honorable Francis W. Sargeant “The Challenge of Tomorrow” November 19, 1968 William D. Hersey “An Amazing Demonstration of Memory” January 28, 1969 Domenic DiMaggio, Former Member, Boston Red Sox “Baseball” November 18, 1969 Frank J. Zeo “What’s Ahead for the Taxpayer?” March 25, 1969 Charles A. Fager, M.D. “The S.S. Hope” January 27, 1970 Ned Martin, Red Sox Broadcaster “Sports” March 31, 1970 David H. Locke, MA State Senator “How Can We Reduce State Taxes?” November 17, 1970 Laurence R. Buxbaum Chief, Consumer Protection Agency February 23, 1971 Steven A. Minter Commissioner of Welfare November 16, 1971 Robert White “The Problem of Shoplifting” January 25, 1972 Nicholas J. Fiumara, M.D. “Boston After Dark” November 14, 1972 E. G. Matthews “The Play of the Senses” January 23, 1973 Joseph M. Jordan “The Vice Scene in Boston” November 13, 1973 Jack Crowley “A Demonstration by the Nether-hair Kennels” January 22, 1974 David R. Palmer “Whither Goest the Market for Securities?” February 19, 1974 David J. Lucey “Your Highway Safety” November 19, 1974 Don Nelson, Boston Celtics “Life Among the Pros” January 28, 1975 The Honorable John W. McCormack, Speaker of the House “Memories of Washington” Speakers_BDA_1966_to_Current Page #1 February 25, 1975 David A. -

Major League Baseball

Appendix 1 to Sports Facility Reports, Volume 5, Number 2 ( Copyright 2005, National Sports Law Institute of Marquette University Law School) MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL Note: Information complied from Sports Business Daily, Forbes.com, Lexis-Nexis, and other sources published on or before January 7, 2005. Team Principal Owner Most Recent Purchase Price Current Value ($/Mil) ($/Mil) Percent Increase/Decrease From Last Year Anaheim Angels Arturo Moreno $184 (2003) $241 (+7%) Stadium ETA Cost % Facility Financing (millions) Publicly Financed Edison 1966 $24 100% In April 1998, Disney completed a $117 M renovation. International Field Disney contributed $87 M toward the project while the of Anaheim City of Anaheim contributed $30 M through the retention Angel Stadium of of $10 M in external stadium advertising and $20 M in Anaheim (2004) hotel taxes and reserve funds. UPDATE On January 4, 2005, team owner Arte Moreno announced that the team would change its name to "The Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim." Moreno believes that the name change will allow the team to tap into a larger marketing area in the greater Los Angeles community. Commissioner Bug Selig has approved the name change, but there are pending lawsuits by the city to enjoin the team, requiring the name to remain "The Anaheim Angels." The city sued arguing that the lease precludes the change, while the team argues that by leaving "Anaheim" in the name, the change satisfies the terms of the lease. NAMING RIGHTS In early 2004 Edison International exercised their option to terminate their 20-year, $50 million naming rights agreement with the Anaheim Angels. -

Cincinnati Reds Press Clippings January 30, 2019

Cincinnati Reds Press Clippings January 30, 2019 THIS DAY IN REDS HISTORY 1919-The Reds hire Pat Moran as manager, replacing Christy Mathewson, when no word is received from him while his is in France with the U.S. Army. Moran would manage the Reds until 1923, collecting a 425-329 record 1978-Former Reds executive, Larry MacPhail, is elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum 1997-The Reds sign Deion Sanders to a free agent contract, for the second time ESPN.COM Busy Reds in on Realmuto, but would he make them a contender? Jan. 29, 2019 Buster Olney ESPN Senior Writer The last time the Cincinnati Reds won a postseason series, Joey Votto was 12 years old, Bret Boone was the team's second baseman and the organization had only recently drafted his kid brother, a third baseman out of the University of Southern California named Aaron Boone. Since the Reds swept the Dodgers in a Division Series in 1995, they have built more statues than they have playoff wins. In recent years, a Dodger said he was sick of Kirk Gibson -- not because of anything Gibson had done, but because the team had felt the need to roll out the highlight of Gibson's epic '88 World Series home run, in lieu of subsequent championship success. Similarly, most of the biggest stars in the Reds organization continue to be Johnny Bench, Joe Morgan, Pete Rose and Tony Perez, as well as announcer Marty Brennaman, who recently announced he will retire after the upcoming season.