Soybean in China: Adaptating to the Liberalization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Competitiveness Analysis of China's Main Coastal Ports

2019 International Conference on Economic Development and Management Science (EDMS 2019) Competitiveness analysis of China's main coastal ports Yu Zhua, * School of Economics and Management, Nanjing University of Science and Technology, Nanjing 210000, China; [email protected] *Corresponding author Keywords: China coastal ports above a certain size, competitive power analysis, factor analysis, cluster analysis Abstract: As a big trading power, China's main mode of transportation of international trade goods is sea transportation. Ports play an important role in China's economic development. Therefore, improving the competitiveness of coastal ports is an urgent problem facing the society at present. This paper selects 12 relevant indexes to establish a relatively comprehensive evaluation index system, and uses factor analysis and cluster analysis to evaluate and rank the competitiveness of China's 30 major coastal ports. 1. Introduction Port is the gathering point and hub of water and land transportation, the distribution center of import and export of industrial and agricultural products and foreign trade products, and the important node of logistics. With the continuous innovation of transportation mode and the rapid development of science and technology, ports play an increasingly important role in driving the economy, with increasingly rich functions and more important status and role. Meanwhile, the competition among ports is also increasingly fierce. In recent years, with the rapid development of China's economy and the promotion of "the Belt and Road Initiative", China's coastal ports have also been greatly developed. China has more than 18,000 kilometers of coastline, with superior natural conditions. With the introduction of the policy of reformation and opening, the human conditions are also excellent. -

Mysteel Raw Materials Daily Bringing You the Latest Updates on China Raw Materials Markets Tuesday, August 2, 2016

Iron Ore Coal & Coke Billet Scrap Ferroalloy Freight Latest News Analysis Data MYSTEEL RAW MATERIAL DEPARTMENT Mysteel Raw Materials Daily Bringing you the latest updates on China raw materials markets www.mysteel.net Tuesday, August 2, 2016 Currency Exchange 1 USD = 6.6277 CNY 1 USD =1.3265AUD 1 USD=3.2648 BRL ISSUE 292 USD/DMT Mysteel IO Index (62% Fe Australia) Today's Highlight 80 70 Steel mills raise steel prices 60 50 Steel prices rose again. Shagang Group issued the early August’s adjustment 40 policy of steel prices on Aug 1th. Rebar price increased by 70 yuan/ton and 16- 30 25mm Spot rebar’s ex-factory price came to 2480 yuan/ton. Coiled rebar price 20 10 increased by 30/ton and 8-10mm spot coiled rebar’s strike price stood at 2530 0 yuan/ton. High speed wire price came to 2480 yuan/ton, up 30 yuan/ton. Hot- rolled coil products’ prices reached 2800-2830 yuan/ton, up 20 yuan/ton. Jul-15 Jul-16 Jan-16 Jun-15 Jun-16 Oct-15 Apr-15 Apr-16 Sep-15 Feb-16 Dec-15 Aug-15 Nov-15 Mar-15 Mar-16 May-15 May-16 USD/tonne Mysteel IO Index VS Mysteel Shanghai Rebar Index USD/dmt Iron ore price hits high 500 80 Iron ore future price 1609 hits three-month high of 486.5 yuan per tonne 450 70 400 60 in Dalian commodity exchange market, and is set to end July with a second 350 consecutive monthly gain, defying market expectations that iron ore would be 300 50 250 40 dragged down by increased supply in 2H16. -

Chinese Express Ingredients and Allergen Information

Asian Ingredient and Allergen Information Item Name Ingredient Statement Allergen Statement Appetizers Chicken Egg Roll (Cabbage, Enriched Bleached Flour [{Wheat Flour, Niacin, Reduced Iron, Thiamine Mononitrate, Riboflavin, Folic Acid}, Calcium Propionate, Malted Barley Flour], Water, White Meat Chicken, Carrots, Onion, Textured Soy Flour, Celery, Enriched Durum Flour [Wheat Flour, Niacin, Ferrous Sulfate, Thiamine Mononitrate, Riboflavin, Folic Acid], Contains 2% or less of: Vegetable Oil [Soybean, Cottonseed, Corn, and/or Canola Oil], Salt, Autolyzed Yeast Extract, Modified Food Starch, Sugar, Garlic, Dried Whole Egg, Soy Sauce Powder [Soy Sauce {Wheat, Soybeans, Salt}, Maltodextrin, Salt], Wheat Gluten, Spice, Cornstarch. Fried in Vegetable Oil [Soybean, Cottonseed, Corn, and/or Canola Oil]), Soybean Oil (Hydrogenated Soybean Oil Chicken Egg Roll with TBHQ and Citric Acid added as preservatives, and Dimethylpolysiloxane added as an anti-foaming agent). Contains Egg, Soy, Wheat. Vegetable Egg Roll (Cabbage, Enriched Flour [{Bleached Wheat Flour, Niacin, Reduced Iron, Thiamine Mononitrate, Riboflavin, Folic Acid}, Calcium Propionate, Malted Barley Flour], Water, Carrots, Broccoli, Water Chestnuts, Enriched Durum Flour [Wheat Flour, Niacin, Ferrous Sulfate, Thiamine Mononitrate, Riboflavin, Folic Acid], Brown Rice, Celery, Bamboo Shoots, Contains 2% or Less of: Salt, Modified Food Starch, Onion, Yeast Extract [Yeast Extract, Sunflower Oil], Toasted Sesame Oil, Flavoring [Yeast Extract, Salt, Maltodextrin, Natural and Artificial Flavor], Vegetable Oil [Cottonseed and/or Canola Oil], Dried Garlic, Wheat Gluten, Sugar, Spice, Eggs, Cornstarch. Fried in Vegetable Oil (Cottonseed and/or Canola Oil), Soybean Oil (Hydrogenated Veggie Egg Roll Soybean Oil with TBHQ and Citric Acid added as preservatives, and Dimethylpolysiloxane added as an anti-foaming agent). Contains Egg, Wheat. -

Soy Free Diet Avoiding Soy

SOY FREE DIET AVOIDING SOY An allergy to soy is common in babies and young children, studies show that often children outgrow a soy allergy by age 3 years and the majority by age 10. Soybeans are a member of the legume family; examples of other legumes include beans, peas, lentils and peanut. It is important to remember that children with a soy allergy are not necessarily allergic to other legumes, request more clarification from your allergist if you are concerned. Children with a soy allergy may have nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, bloody stool, difficulty breathing, and or a skin reaction after eating or drinking soy products. These symptoms can be avoided by following a soy free diet. What foods are not allowed on a soy free diet? Soy beans and edamame Soy products, including tofu, miso, natto, soy sauce (including sho yu, tamari), soy milk/creamer/ice cream/yogurt, soy nuts and soy protein, tempeh, textured vegetable protein (TVP) Caution with processed foods - soy is widely used manufactured food products – remember to carefully read labels. o Soy products and derivatives can be found in many foods, including baked goods, canned tuna and meat, cereals, cookies, crackers, high-protein energy bars, drinks and snacks, infant formulas, low- fat peanut butter, processed meats, sauces, chips, canned broths and soups, condiments and salad dressings (Bragg’s Liquid Aminos) USE EXTRA CAUTION WITH ASIAN CUISINE: Asian cuisine are considered high-risk for people with soy allergy due to the common use of soy as an ingredient and the possibility of cross-contamination, even if a soy-free item is ordered. -

Soy Products As Healthy and Functional Foods

Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research 7 (1): 71-80, 2011 ISSN 1990-9233 © IDOSI Publications, 2011 Soy Products as Healthy and Functional Foods Hossein Jooyandeh Department of Food Science and Technology, Ramin Agricultural and Natural Resources University, Mollasani, Khuzestan, Iran Abstract: Over the recent decades, researchers have documented the health benefits of soy protein, especially for those who take soy protein daily. Soy products offer a considerable appeal for a growing segment of consumers with certain dietary and health concerns. It is quite evident that soy products do reduce the risks of developing various age-related chronic diseases and epidemiologic data strongly suggest that populations that regularly consume soy products have reduced incidence and prevalence of the aforementioned age-related conditions and diseases than populations that eat very little soy. The subject of what specific components is responsible for the plethora of reported health benefits of soybean remains a strong controversial issue, as the scientific community continues to understand what component(s) in soy is /are responsible for its health benefits. Soy constituents’ benefits mostly relate to the reduction of cholesterol levels and menopause symptoms and the reduction of the risk for several chronic diseases such as cancer, heart disease and osteoporosis. A variety of soy products are available on the market with different flavors and textures and a low-fat, nutritionally balanced diet can be developed from them. This article summarized the beneficial health, nutritional and functional properties of the soy ingredients and intends to illustrate the most current knowledge with a consciousness to motivate further research to optimize their favorable effects. -

By Wenrui MA

An Examination of the Application of Power Theory in the Context of the Chinese Seaport Sector by Wenrui MA A Thesis Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Cardiff University Logistics and Operations Management Section of Cardiff Business School, Cardiff University December 2016 DECLARATION This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed ……… ………………… (candidate) Date …………14/03/2017……… STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Signed ……… ………………………… (candidate) Date ………14/03/2017…… STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed ………… ……………………… (candidate) Date …………14/03/2017… STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed …………… …………………… (candidate) Date …………14/03/2017… STATEMENT 4: PREVIOUSLY APPROVED BAR ON ACCESS I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loans after expiry of a bar on access previously approved by the Academic Standards & Quality Committee. Signed …………… …………………… (candidate) Date ……14/03/2017……… i Abstract Power is an essential attribute of all social systems. Nonetheless, the study of this topic has been greatly overlooked in the context of the maritime component of international supply chain management. -

Miso Soup Textured Vegetable Protein (TVP®) Is Similar Serves 4 to Textured Soy Protein

Textured soy protein (TSP) is a highly Choosing processed source of soy protein that appears in Easy, delicious healthy many packaged foods. In bulk form, it readily soy absorbs liquid and takes on the flavor of other ingredients in a recipe. miso soup Textured vegetable protein (TVP®) is similar Serves 4 to textured soy protein. TVP is higher in protein and Preparation: 30 minutes iron than TSP and rich in potassium, magnesium foods 1 and phosphorus. ⁄2 cup onion, chopped 1 Tofu is a soybean curd created by stirring a ⁄2 cup carrot, chopped thickener into warm soy milk. It comes in soft, firm 1 teaspoon sesame oil or extra-firm varieties. Non-silken varieties can be an 4 cups water or stock excellent source of calcium if the thickening agent 2 tablespoons mellow white, barley or brown rice miso contains calcium. 1 ⁄2 cup tofu, any type, cut into small cubes 4 green onions, sliced very thin Buy organic soy Sauté the onion and carrot in sesame oil in a 2-quart soup pot for 3 to 4 minutes. Add Ninety-two percent of the soybeans grown in the water or stock and heat to near boil. Simmer United States today are genetically modified 5 minutes. Dissolve miso in the soup and add to the pot. Add tofu. Simmer about 3 minutes. (GM). To avoid genetically modified foods, Serve garnished with green onion. choose certified organic soy products. The USDA National Organic Standards prohibit genetically modified ingredients in certified To view this brochure, or to explore organic foods. our other product guides, visit pccnaturalmarkets.com/guides • Genetically modified soybeans have significantly less protein and phenylalanine, an essential amino acid. -

Regulation of Intestinal Inflammation by Soybean and Soy-Derived Compounds

foods Review Regulation of Intestinal Inflammation by Soybean and Soy-Derived Compounds Abigail Raffner Basson 1,2,* , Saleh Ahmed 2, Rawan Almutairi 3, Brian Seo 2 and Fabio Cominelli 1,2 1 Division of Gastroenterology & Liver Diseases, School of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH 44106, USA; [email protected] 2 Digestive Health Research Institute, University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, Cleveland, OH 44106, USA; [email protected] (S.A.); [email protected] (B.S.) 3 Department of Pathology, School of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH 44106, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Environmental factors, particularly diet, are considered central to the pathogenesis of the inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. In particular, the Westernization of diet, characterized by high intake of animal protein, saturated fat, and refined carbohydrates, has been shown to contribute to the development and progression of IBD. During the last decade, soybean, as well as soy-derived bioactive compounds (e.g., isoflavones, phytosterols, Bowman-Birk inhibitors) have been increasingly investigated because of their anti-inflammatory properties in animal models of IBD. Herein we provide a scoping review of the most studied disease mechanisms associated with disease induction and progression in IBD rodent models after feeding of either the whole food or a bioactive present in soybean. Keywords: inflammatory bowel disease; isoflavone; bioactive compound; isoflavones; inflammation; Crohn’s disease; western diet; plant-based Citation: Basson, A.R.; Ahmed, S.; Almutairi, R.; Seo, B.; Cominelli, F. Regulation of Intestinal Inflammation by Soybean and Soy-Derived Compounds. Foods 2021, 10, 774. -

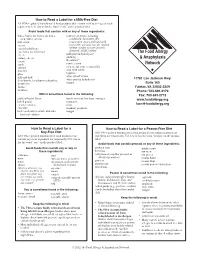

How to Read a Label for a Milk-Free Diet All FDA-Regulated Manufactured Food Products That Contain Milk As an Ingredient Are Required by U.S

How to Read a Label for a Milk-Free Diet All FDA-regulated manufactured food products that contain milk as an ingredient are required by U.S. law to list the word “milk” on the product label. Avoid foods that contain milk or any of these ingredients: butter, butter fat, butter oil, butter milk (in all forms, including acid, butter ester(s) condensed, derivative, dry, buttermilk evaporated, goat’s milk and milk casein from other animals, low fat, malted, casein hydrolysate milkfat, nonfat, powder, protein, caseinates (in all forms) skimmed, solids, whole) cheese milk protein hydrolysate pudding cottage cheese ® cream Recaldent curds rennet casein custard sour cream, sour cream solids diacetyl sour milk solids ghee tagatose whey (in all forms) half-and-half 11781 Lee Jackson Hwy. lactalbumin, lactalbumin phosphate whey protein hydrolysate lactoferrin yogurt Suite 160 lactose Fairfax, VA 22033-3309 lactulose Phone: 703-691-3179 Milk is sometimes found in the following: Fax: 703-691-2713 artificial butter flavor luncheon meat, hot dogs, sausages www.foodallergy.org baked goods margarine caramel candies nisin [email protected] chocolate nondairy products lactic acid starter culture and other nougat bacterial cultures How to Read a Label for a How to Read a Label for a Peanut-Free Diet Soy-Free Diet All FDA-regulated manufactured food products that contain peanut as an All FDA-regulated manufactured food products that ingredient are required by U.S. law to list the word “peanut” on the product contain soy as an ingredient are required by U.S. law to label. list the word “soy” on the product label. -

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of Study Tempeh Is A

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of Study Tempeh is a traditional fermented soybean food. It is a fermented food made by the controlled fermentation of cooked soybeans with a Rhizopus mould as the tempeh starter. The tempeh fermentation by the Rhizopus mould binds the soybeans into compact white cake (Tempeh 2009,25 June). It is made by cooking and dehulling of soybeans and inoculation with different strains of Rhizopus (R. oligosporus, R. oryzae, and R. stolonifer) which will lead to solid substrate fermentation (Steinkraus K.H., 1983). Fermentation also influences the content of desirable constituents such as vitamins, protein and fatty acids (Baumann U., 1995). Tempeh provides the staple food for a large population in Indonesia and Malaysia. Like tofu, tempeh is made from soybeans, but tempeh is a whole soybean product with different nutritional characteristics and also different textural qualities. Tempeh’s fermentation process and its retention of the whole bean give it higher content of protein, dietary fiber and vitamins compared to tofu, as well as firmer texture and also with stronger flavor. Because of its nutritional value, tempeh is used worldwide in vegetarian cuisine. Tempeh is a low cost nutritious food and can be consumed by all socio-economic groups. 2 Figure 1.1 : A piece of uncooked tempe Table 1.1: Nutritional table for 100g of Tempe Water 54.9 g Energy 199 kcal Energy 833 kJ Protein 19.0 g Fat 7.7 g Sat. fatty acids 1.11 g Mono-unsat. fatty acids 1.7 g Poly-unsat. fatty acids 4.3 g Carbohydrates 17.0 g Fiber -

Soybean Oil Was Considered Neither a Good Industrial Paint Oil Nor a Good Edible Oil

Reprinted from THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN OIL CHEMISTS' SOCIETY, Vol. 58, No.3 Pages: 234-236 (1981) 4798 Purchased by U. S. Dept. ot AsricuJture for Official U History of the Development of Soy Oil for Edible Uses H.J. DUTTON, Northern Regional Research Center, Agricultural Research, Science and Education Administration, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Peoria, IL 61604 in the U.S., moreover, increasing outlets appear to be assured in the ABSTRACT world markets of the future. In the early 1940s, soybean oil was considered neither a good industrial paint oil nor a good edible oil. The history of soybean oil Soybeans were discovered by man before the building of is a story of progress from a minor, little-known, p.roblem oil to a Tenochtitlan by the Aztecs, before the advanced cultural major source of edible oil proudly labeled on premium products in the 1980s. It is also a story of cooperative government research development of the Mayas and the large-scale architecture and industrial implementation of research findings. After 3-1/2 of Teatihuacan by the Toltecs. Soybeans predate the pyra decades, soybean oil, "the number one problem of the soybean mids, were grown before the building of the Tower of industry," has become the source of choice for edible oil products Babel, and came centuries before Solomon fashioned his 234 I JADeS March 1981 SOYA OIL-Dutton temple. As one of the oldest of crops cultivated by man, John C. Cowan, Northern Regional Research Laboratory they were grown in China before records were kept (1). -

Soy Allergy Avoidance List Hidden Names for Soy Compiled by Debra A

Soy Allergy Avoidance List Hidden Names for Soy Compiled by Debra A. Indorato RD, LDN, member of KFA’s Medical Advisory Team Foods covered by the FDA labeling laws that contain soy must be labeled in plain English to declare that it “contains soy.” However, there are many foods and products that are not covered by FDA allergen labeling laws, so it is still important to know how to read a label for soy ingredients. Products exempt from plain English labeling rules: foods that are not regulated by the FDA (tinyurl.com/KFA-FALCPA), cosmetics and personal care products, prescription and over-the-counter medications or supplements, pet food, toys and crafts. contain soy The following ingredients found on a label indicate the presence of soy protein. All labels should be read carefully before consuming a product, even if it has been used safely in the past. Bean curd Soya may contain soy Edamame (soybeans in pods) Soya Flour Artificial flavoring Hydrolyzed soy protein Soybeans Asian foods (e.g. Japanese, Kinnoko flour Soybean granules Chinese, Thai, etc.) Kyodofu (freeze dried tofu) Soybean curd Hydrolyzed plant protein Miso Soybean flour Hydrolyzed vegetable protein (HVP) Natto Soy lecithin* Natural flavoring Okara (soy pulp) Soybean paste Vegetable broth Shoyu sauce Supro Vegetable gum Soy albumin Tamari Vegetable starch Soy bran Tempeh Soy concentrate Teriyaki sauce should be safe Soy oil (except cold pressed, expeller Soy fiber Textured soy flour (TSF) pressed or extruded soybean oil) Soy flour Textured soy protein (TSP) Soy formula Textured vegetable protein (TVP) Vegetable oil derived from soy Soy grits Tofu These soy derivatives should be safe Soy milk Yakidofu for most soy-allergic individuals.