University of Warwick Institutional Repository

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DA 1/2015 in the Matter Between: HOSPERSA OBO TS TSHAMBI

IN THE LABOUR APPEAL COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA, DURBAN Reportable Case no: DA 1/2015 In the matter between: HOSPERSA OBO TS TSHAMBI Appellant and DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, KWAZULU –NATAL Respondent Heard: 25 February 2016 Delivered: 24 March 2016 Summary: Section 24 of the LRA provides for arbitration of disputes about the ‘interpretation or application’ of collective agreements– interpretation of – section provides for a dispute resolution device ancillary to collective bargaining, not to be used to remedy an unfair labour practice under pretext that a term of a collective agreement has been breached. The phrase ‘interpretation or application’ is not to be read disjunctively – the ‘enforcement’ of the terms of a collective agreement is a process which follows on a positive finding about ‘application’ not a facet of ‘application’. A dispute about an employer’s failure to pay an employee during period of suspension pending a disciplinary enquiry is, properly characterised, an unfair labour practice about unfair suspension as contemplated in section 186(2) (b) of the LRA. 2 An arbitrator must characterise a dispute objectively, not slavishly defer to the parties’ subjective characterisation- failure to do so is an irregularity. The determination of what constitutes a reasonable time within which to refer a dispute when no fixed period is prescribed for that category of dispute, such as a section 24 dispute, is a fact-specific enquiry having regard to the dynamics of labour relations considerations – where for example the dispute may be understood as a money claim, the prescription laws are irrelevant. Labour court reviewing and setting aside award in which arbitrator deferred to an incorrect characterisation of a dispute and ordering the matter to be heard afresh upheld and appeal against order dismissed. -

This Book Compares Resistance to Technology Across Time, Nations and Tech- Nologies

This book compares resistance to technology across time, nations and tech- nologies. Three post-war technologies - nuclear power, information technology and biotechnology - are used in the analysis. The focus is on post-1945 Europe, with comparisons made with the USA, Japan and Australia. Instead of assuming that resistance contributes to the failure of a technology, the main thesis of this book is that resistance is a constructive force in technological development, giving technology its particular shape in a particular context. Whilst many people still believe in science and technology, many have become more sceptical of the allied 'progress'. By exploring the idea that modernity creates effects that undermine its own foundations, forms and effects of resistance are explored in various contexts. The book presents a unique interdisciplinary study, including contributions from historians, sociologists, psychologists and political scientists. Resistance to new technology Resistance to new technology nuclear power information technology and biotechnology edited by MARTIN BAUER The National Museum WigRTof Science & Industry Science Museum 31 CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building. Trumpington Street, Cambridge CB2 1RP, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, United Kingdom 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia © Cambridge University Press 1995 This book is in copyright. -

Trade Union Collective Identity, Mobilisation and Leadership – a Study of the Printworkers’ Disputes of 1980 and 1983

Trade Union collective identity, mobilisation and leadership – a study of the printworkers’ disputes of 1980 and 1983 Nigel Costley 1 2 University of the West of England Collective identity and strategic choice – a study of the printworkers’ disputes of 1980 and 1983 Nigel Costley A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of the West of England, Bristol for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Bristol Business School, University of the West of England 2021 3 Declaration I declare that this research thesis is my own, unaided work. It is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of the West of England, Bristol for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Nigel Costley Date 4 Copyright This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. Acknowledgements Thanks to Professor Stephanie Tailby, Professor Sian Moore and Dr Mike Richardson for their continuous encouragement, support and constructive criticisms. 5 Abstract The National Graphical Association (NGA) typified the British model of craft unionism with substantial positional power and organisational strength. This study finds that it relied upon, and was reinforced by, the common occupational bonds that members identified with. It concludes that the value of collective identity warrants greater attention in the debate over union renewal alongside theories around mobilisation and organising (Kelly 2018), alliance-building and social movements (Holgate 2014). Sectionalism builds solidarity through the exclusion of others. Occupational identity is vulnerable to technological change. This model neglects institutional and ‘associational’ power, eschewing legal protections in favour of collective bargaining and ignoring alliance-building in favour of sovereign authority. -

Enterprise Bargaining Agreements and the Requirement to ‘Consult’

About the Institute of Public Affairs The Institute of PuBlic Affairs is an independent, non-profit puBlic policy think tank, dedicated to preserving and strengthening the foundations of economic and political freedom. Since 1943, the IPA has been at the forefront of the political and policy debate, defining the contemporary political landscape. The IPA is funded By individual memBerships and subscriptions, as well as philanthropic and corporate donors. The IPA supports the free market of ideas, the free flow of capital, a limited and efficient government, evidence-Based puBlic policy, the rule of law, and representative democracy. Throughout human history, these ideas have proven themselves to be the most dynamic, liBerating and exciting. Our researchers apply these ideas to the puBlic policy questions which matter today. About the authors Gideon Rozner is an Adjunct Fellow at the Institute of PuBlic Affairs. He was admitted to the Supreme Court of Victoria in 2011 and spent several years practicing as a lawyer at one of Australia’s largest commercial law firms, as well as acting as general counsel to an ASX-200 company. Gideon has also worked as a policy adviser to ministers in the AbBott and TurnBull Governments. Gideon holds a Bachelor of Laws (Honours) and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of MelBourne. Aaron Lane is a Legal Fellow at the Institute of PuBlic Affairs. He specialises in employment, industrial relations, regulation and workplace law. He is a lawyer, admitted to the Supreme Court of Victoria in 2012. He has appeared before the Fair Work Commission, the Productivity Commission, and the Senate Economics Committee, among other courts and triBunals. -

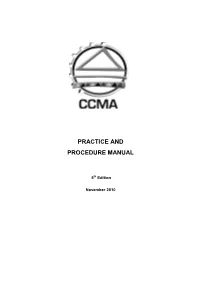

Practice and Procedure Manual

PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE MANUAL 5th Edition November 2010 101 Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction 101 Chapter 2 Functions, Jurisdiction and Powers Generally 201 Chapter 3 Notice and service 301 Chapter 4 Representation 401 Chapter 5 Referrals and initial administration 501 Chapter 6 Pre-conciliation 601 Chapter 7 Con-Arb 701 Chapter 8 Conciliation 801 Chapter 9 Certificates 901 Chapter 10 Settlement agreements 1001 Chapter 11 Request for arbitration, pre-arbitration procedures and subpoenas 1101 Chapter 12 Arbitrations 1201 Chapter 13 Admissibility and evaluation of evidence 1301 Chapter 14 Awards 1401 Chapter 15 Applications 1501 Chapter 16 Condonation applications 1601 Chapter 17 Rescissions and variations 1701 Chapter 18 Costs and taxation 1801 Chapter 19 Enforcement of settlement agreements and arbitration awards 1901 Chapter 20 Pre-dismissal arbitration 2001 Chapter 21 Review of arbitration awards 2101 Chapter 22 Contempt of the Commission 2201 Chapter 23 Facilitation of retrenchments in terms of section 189A of the LRA 2301 Chapter 24 Intervention in disputes in terms of section 150 of the LRA 2401 102 Chapter 25 Record of proceedings 2501 Chapter 26 Demarcations 2601 Chapter 27 Picketing 2701 Chapter 28 Diplomatic consulates and missions and international organisations 2801 Chapter 29 Index 2901 101 Chapter 1: Introduction 1.1 This manual records the practices and procedures of the CCMA. It is a work in progress and the intention is to continuously improve and update it, particularly as and when practices and procedures change. The manual is written in a question and answer format. It was not intended to cover every possible question. The questions covered are those which most commonly arise in the every day work environment. -

Copyright Cluedo Find Whodunnit and Get Them to Pay Contents

MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL UNION OF JOURNALISTS WWW.NUJ.ORG.UK | JULY-AUGUST 2018 Copyright Cluedo Find whodunnit and get them to pay Contents Main feature 12 Close in and win The quest for copyright justice News opyright has been under sustained 03 STV cuts jobs and closes channel attack in the digital age, whether it is through flagrant breaches by people Pledge for no compulsory redundancies hoping they can use photos and 04 Call for more disabled people on TV content without paying or genuine NUJ backs campaign at TUC conference Cignorance by some who believe that if something is downloadable then it’s free. Photographers 05 Legal action to demand Leveson Two and the NUJ spend a lot of time and energy chasing copyright. Victims get court go-ahead This edition’s cover feature by Mick Sinclair looks at a range of 07 Al Jazeera staff win big pay rise practical, good-spirited ways of making sure you’re paid what Deal reached after Acas talks you’re owed. It can take a bit of detective work. Data in all its forms is another big theme of this edition. “Whether it’s working within the confines of the new general Features data protection regulations or finding the best way to 10 Business as usual? communicate securely with sources, data is an increasingly What new data rules mean for the media important part of our work. Ruth Addicott looks at the implications of the new data laws for journalists and Simon 13 Safe & secure Creasey considers the best forms of keeping communication How to communicate confidentially with sources private. -

Industrial Relations Act 2016

Queensland Industrial Relations Act 2016 Current as at 31 August 2017 Queensland Industrial Relations Act 2016 Contents Page Chapter 1 Preliminary Part 1 Introduction 1 Short title . 47 2 Commencement . 47 3 Main purpose of Act . 47 4 How main purpose is primarily achieved . 48 5 Act binds all persons . 50 Part 2 Interpretation 6 Definitions . 50 7 Who is an employer . 50 8 Who is an employee . 51 9 What is an industrial matter . 51 Part 3 General overview of scope of Act 10 Purpose of part . 52 11 Definition for part . 52 12 Who this Act applies to generally . 52 13 Who this Act applies to—particular provisions . 54 Chapter 2 Modern employment conditions Part 1 Preliminary 14 Definitions for chapter . 54 15 Meaning of long term casual employee . 55 Part 2 Interaction of elements of industrial relations system 16 What part is about . 55 17 Relationship between Queensland Employment Standards and other laws . 56 18 Relationship between Queensland Employment Standards and industrial instruments . 56 Industrial Relations Act 2016 Contents 19 Relationship of modern award with certified agreement . 56 20 Relationship of modern award with contract of service . 57 Part 3 Queensland Employment Standards Division 1 Preliminary 21 Meaning of Queensland Employment Standards . 57 Division 2 Minimum wage 22 Entitlement to minimum wage . 58 Division 3 Maximum weekly hours 23 Maximum weekly hours . 58 24 Applicable industrial instruments may provide for averaging of hours of work . 59 25 Averaging of hours of work for employees not covered by applicable industrial instruments . 60 26 Deciding whether additional hours are reasonable . -

A REPLY to MARTIN SHAW Ian H. Birchall

THE PREMATURE BURIAL: A REPLY TO MARTIN SHAW Ian H. Birchall Martin Shaw's 'unofficial' history of the International Socialists1 makes an important contribution to the debate that has been taking place, over the last few years, in the pages of The Socialist Register about the sort of organization that the British left needs. Shaw has written, firmly if not without melancholy, an obituary for the political tendency represented by the International Socialists and (since 1977) the Socialist Workers Party. By 1976, Shaw tells us, the organization was 'radically deformed'; its politics had become 'opportunistic, unrealistic and sectarian'; its 'degeneration' repre- sented a 'squandering of the potential for a new socialist movement'; it had undergone 'catastrophic changes'.* These are serious charges and require a cool and objective response. Every failure has its lessons and every defeat is a stepping-stone to final victory. For example, the IS/SWP represents the most serious and consistent attempt in recent years to build a revolutionary socialist organization outside of and independent from the Labour Party. An acceptance of Shaw's case would be a strong argument on the side of those who believe that Marxists must continue to work within the Labour Party. Moreover, any SWP member who reads Shaw's article will be willing to concede that some of Shaw's specific criticisms are at least partially correct. All the more pity that Shaw frames them in the context of an article which uses the weaknesses as the proof of irredeemable corruption rather than asking how they may best be corrected. Shaw makes a wide range of criticisms, but behind them lie two fundamental points: firstly, that the IS/SWP has failed to develop an adequate form of internal democracy; secondly, that the IS/SWP is guilty of a political deviation described as 'workerism'. -

Faces of Non-Union Representation in the UK: Management Strategies, Processes and Practice

Paul J. Gollan Faces of non-union representation in the UK: management strategies, processes and practice Conference Paper Original citation: Originally presented at Industrial Relations Association World Congress, 8-12 September 2003, Berlin. This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/20456/ Available in LSE Research Online: August 2008 A later version of this paper was published in International employment relations review, 9 (2), 2003. © 2003 Paul J. Gollan LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. Special Seminar - New Forms of Organisation, Partnership and Interest Representation International Industrial Relations Association World Congress Berlin, 8-12 September, 2003 Faces of non-union representation in the UK – Management strategies, processes and practice Paul J. Gollan Draft Only Department of Industrial Relations London School of Economics Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE Email: [email protected] (No part of this paper is to be cited without prior permission) 1 Faces of non-union representation in the UK – Management strategies, processes and practice This paper will attempt to examine non-union employee representation1 (NER) structures in the UK and, in particular assess management strategies, processes and practice of NER arrangements in nine organisations. -

Joint Industrial Councils in Great Britain: Reports of Committee On

U. S. DEPARTMENT OF LABOR BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS ROYAL MEEKER, Commissioner BULLETIN OF THE UNITED STATES\ (M OCC BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS/ * # * ( IlO . ZDD LABOR AS AFFECTED BY THE WAR SERIES JOINT INDUSTRIAL COUNCILS IN GREAT BRITAIN REPORTS OF COMMITTEE ON RELATIONS BETWEEN EMPLOYERS AND EMPLOYED, AND OTHER OFFICIAL DOCUMENTS JULY, 1919 W ASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1919 Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis CONTENTS. Page. Introduction and summary............................................................................... 5-15 Summary of publications reproduced in this bulletin................................. 7-10 Progress of organization of joint industrial councils................................... 10-14 Whitley plan in industrial establishments controlled by Government departments..................................................................................... 12-14 Report on Whitley councils by Department of Labor commission of employers............................................................................................... 14,15 Reports of committee on relations between employers and employed............... 16-44 Interim report on joint standing industrial councils.................................. 16-23 Appendix............................................................................................. 22, 23 Second report on joint standing industrial councils....................................24-31 -

Interpretation of Union Membership Eligibility Rules in the Modern Award Era

SHIFTING THE GOALPOSTS: INTERPRETATION OF UNION MEMBERSHIP ELIGIBILITY RULES IN THE MODERN AWARD ERA Australian Labour Lawyers Association 8th National Conference, 4-5 November 2016, Melbourne Daniel White1 (Special Counsel, Perth), Mills Oakley Lawyers, [email protected] Abstract The interpretation of union membership eligibility rules (union rules) has attracted considerable attention from Courts and Tribunals. The amalgamation of unions over the years has by no means assisted, resulting in ambiguous and confusing union rules which are very difficult to interpret. Union rules also overlap considerably, resulting in claims of membership coverage by multiple unions paving the way for costly demarcation disputes. As of 1 July 2009 the new Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) placed unions as bargaining representatives at centre stage of the collective enterprise-based bargaining regime. The result has drawn particular focus back to union rules as the source of eligibility to be a bargaining representative and the rights and obligations that flow from that. Awards have historically played an important role in carving out union “turf” under previous legislative schemes and thus assisted in defining the scope of union rules. However as of 1 January 2010, the introduction of Modern Awards, which do not name unions as being “a party”, has opened up the way for some unions to contest coverage and even venture into “new turf”. This paper will reflect on the key decisions concerning the interpretation of union rules, examine the patterns/trends taken by the Courts and Tribunals concerning union rules in the Modern Award era (particularly around bargaining) and promote some ideas for further debate around union rules. -

Employment & Labour Law 2018

ICLG The International Comparative Legal Guide to: Employment & Labour Law 2018 8th Edition A practical cross-border insight into employment and labour law Published by Global Legal Group with contributions from: A. Lopes Muniz Advogados Associados Koushos Korfiotis Papacharalambous LLC BAS – Sociedade de Advogados, SP, RL Lakshmikumaran & Sridharan Carnelutti Law Firm Latournerie Wolfrom Avocats CDZ Legal Advisors Law firm Šafar & Partners, Ltd Debarliev, Dameski and Kelesoska, Attorneys at Law Mariscal & Abogados, Asociados Deloitte Kosova Sh.p.k. McCann FitzGerald Deloitte Legal Sh.p.k. Meridian Law Chambers DQ Advocates Limited Mori Hamada & Matsumoto EmpLaw Advokater AB Pachiu & Associates Erdinast, Ben Nathan, Toledano & Co. Advocates People + Culture Strategies FCLAW – LAWYERS & PRIVATE NOTARIES Rátkai Law Firm GANADO Advocates SEUM Law Global Law Office Shahid Law Firm Gün + Partners Skrine Gürlich & Co. Stikeman Elliott LLP Hamdan AlShamsi Lawyers and Legal Consultants Sulaiman & Herling Attorneys at Law Hogan Lovells Udo Udoma & Belo-Osagie Homburger Wildgen S.A. Hughes Hubbard & Reed LLP Winkler Partners The International Comparative Legal Guide to: Employment & Labour Law 2018 General Chapter: 1 Where Next for the Gig Economy? – Stefan Martin & Jo Broadbent, Hogan Lovells 1 Country Question and Answer Chapters: 2 Albania Deloitte Legal Sh.p.k.: Sabina Lalaj & Ened Topi 5 Contributing Editors Stefan Martin & 3 Australia People + Culture Strategies: Joydeep Hor & Therese MacDermott 15 Jo Broadbent, Hogan Lovells 4 Bahamas Meridian Law Chambers: Dywan A – G. R. Rodgers 22 Sales Director Florjan Osmani 5 Brazil A. Lopes Muniz Advogados Associados: Antônio Lopes Muniz & Zilma Aparecida S. Ribeiro 28 Account Director Oliver Smith 6 Canada Stikeman Elliott LLP: Patrick L.