Evolution, Child Abuse and the Constitution Christopher Malrborough

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE DESCENT of MADNESS: Evolutionary Origins of Psychosis

THE DESCENT OF MADNESS Drawing on evidence from across the behavioural and natural sciences, this book advances a radical new hypothesis: that madness exists as a costly consequence of the evolution of a sophisticated social brain in Homo sapiens. Having explained the rationale for an evolutionary approach to psych- osis, the author makes a case for psychotic illness in our living ape relatives, as well as in human ancestors. He then reviews existing evolutionary theor- ies of psychosis, before introducing his own thesis: that the same genes causing madness are responsible for the evolution of our highly social brain. Jonathan Burns’ novel Darwinian analysis of the importance of psychosis for human survival provides some meaning for this form of suffering. It also spurs us on to a renewed commitment to changing our societies in a way that allows the mentally ill the opportunity of living. The Descent of Madness will be of interest to those in the fields of psychiatry, psychology, sociology and anthropology, and is also accessible to the general reader. Jonathan Burns is chief specialist psychiatrist at the Nelson Mandela School of Medicine. His main areas of research include psychotic illnesses, human brain evolution and evolutionary origins of psychosis. THE DESCENT OF MADNESS Evolutionary Origins of Psychosis and the Social Brain Jonathan Burns First published 2007 by Routledge 27 Church Road, Hove, East Sussex BN3 2FA Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2007 Jonathan Burns This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2007. -

Raising-Darwins-Consciousness.Pdf

RAISING DARWIN'S CONSCIOUSNESS Female Sexuality and the Prehominid Origins of Patriarchy Sarah Blaffer Hrdy University of California, Davis Sociobiologists and feminists agree that men in patriarchal social systems seek to control females, but sociobiologists go further, using Darwin's theory of sexual selection and Trivers's ideas on parental investment to explain why males should attempt to control female sexuality. From this perspective, the stage for the development under some conditions of patriarchal social systems was set over the course of primate evolution. Sexual selection encompasses both competition between males and female choice. But in applying this theory to our "lower origins" (pre- hominid ancestors), Darwin assumed that choices were made by essen- tially "coy" females. I argue here that female solicitation of multiple males (either simultaneously or sequentially, depending on the breeding system) characterized prehominid females; this prehominid legacy of cy- clical sexual assertiveness, itself possibly a female counter-strategy to male efforts to control the timing of female reproduction, generated fur- ther male counter-strategies. This dialectic had important implications for emerging hominid mating systems, human evolution, and the devel- opment of patriarchal arrangements in some human societies. For homi- nid males who will invest in offspring, there would be powerful selection for emotions, behaviors, and customs that ensure them certainty of pater- nity. The sexual modesty that so struck Darwin can be explained as a recent evolved or learned (perhaps both) adaptation in women to avoid penalties imposed by patrilines on daughters and mates who failed to conform to the patriline's prevailing norms for their sex. -

Iciumv LEADERS in ANIMAL BEHAVIOR the Second Generation

UO1BJ3U3D iciumv LEADERS IN ANIMAL BEHAVIOR The Second Generation Edited by Lee C. Drickamer Northern Arizona University Donald A. Dewsbury University of Florida CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS 13 Myths, monkeys, and motherhood: a compromising life SARAH BLAFFER HRDY Definition of an Anthropologist: "(Someone) who studies human nature in all its diversity." Carmelo Lison-Tolosana (1966) Maternal effects (1946-64) From a young age, I was interested in why humans do what they do. With little exposure to science, certainly no inkling that there might be people in the world who studied other animals in order to better understand our species, I decided to become a novelist. Born in Leaders in Animal Behavior: The Setond Generation, ed. L. C. Drickamcr & D. A. Dewsbury. Published by Cambridge University Press. CO Cambridge University Press 2010. 344 Sarah Bluffer Hrdy Texas in 1946, right at the start of the postwar baby boom, I was the third of five children - Speedway. Prevailin four daughters and finally the long-awaited son. My father's father, R. L. Blaffer, had come segregation, and pi to Texas from Hamburg via New Orleans in 1901 at the time oil was discovered at interested in the e1 Spindletop. He recognized that fortunes would be made in the oil business. He married inheritance, female Sarah Campbell from Lampasas, whose father was in that business. I was named for her, the women's moven Sarah Campbell Blaffer II. My mother's father's ancestors, the Hardins, French Huguenots Reared by a suo from Tennessee, arrived earlier, in 1825, before Texas was even a state. -

Cinderella Effect Facts

The “Cinderella effect”: Elevated mistreatment of stepchildren in comparison to those living with genetic parents. Martin Daly & Margo Wilson Department of Psychology, Neuroscience & Behaviour McMaster University Hamilton, Ontario, Canada L8S 4K1 <[email protected]> <[email protected]> Theory Parents commit a huge amount of time, attention and material resources to the care of their children, as well as incurring life-threatening risks to defend them and bodily depletion to nourish them. Why are parents motivated to invest so heavily in their children? From an evolutionary perspective, the answer is surely that natural selection has favoured intensive parental care in our lineage. Those ancestral genotypes and phenotypes that best succeeded in raising children to become reproducing adults were the ones that persisted and proliferated. If the psychological underpinnings of parental care have indeed evolved by natural selection, we may furthermore anticipate that parental feeling and action will not typically be elicited by just any random conspecific juvenile. Instead, care-providing animals may be expected to direct their care selectively towards young who are (a) their own genetic offspring rather than those of their reproductive rivals, and (b) able to convert parental investment into increased prospects for survival and reproduction. This is the kernel of the theory of discriminative parental solicitude, which (notwithstanding some interesting twists and caveats) has been abundantly verified in a broad range of care-giving species -

Evolutionary Psychology As a Unifying Framework and Meta-Theory

Part V | Chapter 1 Chapter 1 Ultimate explanations: Evolutionary psychology as a unifying framework and meta-theory The term ‘evolutionary psychology’ (EP) was coined during “lengthy and intensive debates about how to apply evolution to behavior” (Tooby & Cosmides, 2005, p. 15) between Martin Daly, Margo Wilson, Don Symons, John Tooby, Leda Cosmides, and David Buss in the 1980s. It is a relatively young and developing way of thinking in psychology that can serve as a meta-theoretical framework, as it builds directly on the foundations of biology. More spe- cifically, EP is based on the only scientific explanation for the complexity of earthly life forms, namely evolution by natural selection. In the scientific community, it is largely ac- knowledged that humans are a product of evolution by natural selection too. We are mammals belonging to the branch of the tree of life called primates and our closest living relatives are the chimpanzees and bonobos, with whom we share a common ancestor that lived some 6 to 7 million years ago. Though such long time spans are beyond our ‘natural’ capacity to comprehend, consider this: the process of evolving from a light-sensitive cell to a human eye can happen in fewer than 400,000 years (Nilsson & Pelger, 1994). Researchers named our species homo sapiens and contemporary researchers have deter- mined our ‘start date’ to be at least 300,000 years ago, based on new homo sapiens findings in Morocco (Hublin et al., 2017). ‘Start date’ is a bit of a misleading term, as there is of course no ‘sudden appearance,’ but a very slow, invisible, and gradual change. -

An Evolutionary Solution to Manslaughter Mitigation

Emory Law Journal Volume 62 Issue 1 2012 Principles for Passion Killing: An Evolutionary Solution to Manslaughter Mitigation D. Barret Broussard Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/elj Recommended Citation D. B. Broussard, Principles for Passion Killing: An Evolutionary Solution to Manslaughter Mitigation, 62 Emory L. J. 179 (2012). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/elj/vol62/iss1/3 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Emory Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Emory Law Journal by an authorized editor of Emory Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BROUSSARD PROOFS1 10/31/2012 7:49 AM PRINCIPLES FOR PASSION KILLING: AN EVOLUTIONARY SOLUTION TO MANSLAUGHTER MITIGATION† ABSTRACT The law recognizes the frailty of human nature by mitigating murder to manslaughter when committed in the heat of passion or under extreme emotional disturbance. Evolutionary analysis entails the scientific study of the principles of human nature. Yet, the law’s understanding of human nature is not congruent with evolutionary analysis. To be legally provoked under common law for manslaughter mitigation, a homicide must be in response to one of four kinds of provocation: adultery, mutual combat, false arrest, and violent assault. And under adultery, only sexual infidelity counts. Sexual infidelity is not the only type of infidelity that can push a person into a homicidal rage, and while American jurisdictions have started moving away from the rigid categories, sexual infidelity remains a paradigmatic approach for mitigation. The Model Penal Code attempted to make the law more contextual, but it created a new series of adjudications that are expansive and also incongruent with evolutionary analysis. -

My Background, Research Interests, and Future Plans by Geoffrey Miller

My background, research interests, and future plans By Geoffrey Miller Miller, G. F. (2011). My background, research interests, and future plans. In X.T. Wang & Su, Y.-J. (Ed.), Thus spake evolutionary psychologists (进化心理学家如是说), pp. 320-328. Beijing: Peking University Press. After I got a B.A. in psychology and biology from Columbia University, I went to graduate school in psychology at Stanford in 1987. I intended to study cognitive psychology, but found it too boring and abstract. Fortunately, two founders of evolutionary psychology – Leda Cosmides and John Tooby – were working as post-docs with my advisor Roger Shepard. Along with David Buss, Martin Daly, Margo Wilson, and Gerd Gigerenzer – who were visiting Stanford in 1989- 1990 – they introduced me to the possibility of applying evolutionary theory to study human nature. After that, my Stanford friend Peter Todd and I knew that we wanted to join this new field of evolutionary psychology, but we weren’t quite sure what research to do. We had learned about genetic algorithms – ways of simulating evolution by natural selection in computers – and we applied them to designing neural networks for learning some simple tasks. We hoped to illustrate how evolution and learning could interact to produce adaptive behavior. Our research led to my post-doc at University of Sussex in England in the early 1990s, working on artificial life and evolutionary robotics. That was fun, but I realized that I was more interested in human psychology than in cognitive engineering. At Stanford, I also grew interested in sexual selection through mate choice. It seemed like a very powerful but neglected process, not only for explaining sex differences in bodies and brains, but also for explaining the fast evolution of any extravagant mental abilities, whether bird song or human language. -

The Cinderella Effect: Parental Discrimination Against Stepchildren the Cinderella Effect: Parental Discrimination Against Stepchildren

The Cinderella Effect: Parental Discrimination against Stepchildren The Cinderella Effect: Parental Discrimination against Stepchildren Cinderella stories about abused stepchildren are cross-culturally universal. Are they founded in reality? Because Darwinian selection shapes social motives and behavi- our to be effectively nepotistic, an obvious hypothesis is that stepparents will be over- represented among those who mistreat children. This possibility was long neglected, but stepparenthood has turned out to be the most powerful epidemiological risk fact- or for child abuse and child homicide yet known. Moreover, non-violent discriminati- on against stepchildren is substantial and ubiquitous. Martin Daly, Professor, Margo Wilson, Professor, Department of Psychology, Department of Psychology, McMaster University McMaster University Parents are Discriminative Nepotists selectively toward close relatives of the caretaker. A cornerstone of evolutionary psychology is the Usually, this means the caretaker’s own offspring. proposition that Darwinian selection shapes social Imagine a population of animals in which there are motives and behaviour to be effectively »nepotis- two alternative, heritable types of parental psyche. tic«, that is, to contribute selectively to the well-be- Type A invests its time and energy selectively in the ing and eventual reproduction of the actors’ genetic care of its own young, who are better than average relatives. In any species, the genes and traits that bets to be carriers of the same heritable tendencies. persist and proliferate over generations are those Type B nurtures any youngster in need, regardless whose direct and indirect effects cause them to of which type of behaviour it will display when it replicate at higher rates than alternative genes and later becomes a parent itself. -

![Springer MRW: [AU:, IDX:]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5578/springer-mrw-au-idx-2285578.webp)

Springer MRW: [AU:, IDX:]

M Martin Daly and Margo Wilson inconsistencies between evolutionary logic and observed crime statistics in industrialized, West- Gavin Vance and Todd K. Shackelford ern cities like Chicago and Detroit. They argued Oakland University, Rochester, MI, USA that available data on violent crime are vulnerable to misinterpretations and erroneous conclusions, such as the belief that the majority of homicides Synonyms are committed against kin. However, the factual basis of this claim relies largely on one’sdefini- Aggression; Crime; Homicide; Intimate Partner tion of kin. The kin altruism hypothesis predicts Violence that, because individuals share roughly 50% of their genes with full siblings, biological children, or parents, an individual may aid copies of his or Definitions her own genes by behaving altruistically toward these individuals (Hamilton, 1964). Therefore, if Martin Daly is an evolutionary psychologist who humans regularly engaged in the killing of genet- received his Ph.D. from the University of Toronto. ically related kin, this would pose a considerable Margo Wilson was an evolutionary psychologist contradiction between patterns of human aggres- who received her Ph. D from University College sion and the theory of evolution by natural selec- London. Together, Daly and Wilson applied an tion (Darwin, 1859). Daly and Wilson explain that evolutionary perspective to crime statistics to pro- crime statistics like those from Chicago and vide an explanation for patterns of violence and Detroit do not present a conflict with evolutionary homicide in modern human societies. theory because many of the homicide victims Martin Daly and Margo Wilson were a reported as “kin” in police records are not genet- husband-wife research team who, together, inves- ically related to the perpetrator. -

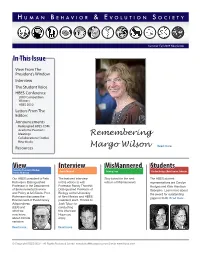

HBES Newsletter Summer 2009

H UMAN BE H AVIOR & EVOLUTION SOCIETY Summer-Fall 2009 Newsletter In This Issue View From The President’s Window Interview The Student Voice HBES Conference 2009 Competition Winners HBES 2010 Letters From The Editors Announcements Redesigned HBES.COM Academic Positions Meetings Remembering Collaborations/Studies New Books Resources Margo Wilson Read more... View Interview MisMannered Students From the President’s Window Randy Thornhill Coming Soon Carolyn Hodges | Kate Hanson Sobraske Peter J. Richerson Our HBES president is Pete The featured interview Stay tuned for the next The HBES student Richerson, Distinguished in this edition is with edition of Mismannered. representatives are Carolyn Professor in the Department Professor Randy Thornhill, Hodges and Kate Handson of Environmental Science Distinguished Professor of Sobraske. Learn more about and Policy at UC Davis. Prof. Biology at the University the award for outstanding Richerson discusses the of New Mexico and HBES paper in EHB. Read more... Environment of Evolutionary president-elect. Thanks to Adaptedness Josh Tybur for (EEA) and conducting what we this interview. now know Hope you about climate enjoy. variation. Read more... Read more... © Copyright HBES 2007 - All Rights Reserved | email: [email protected] | web: www.hbes.com Remembering Margo Wilson HBES’ great friend Margo Wilson passed away after a long and courageous battle with lymphoma. Margo’s intellectual contribution to our field through her work with Martin Daly on homicide is an enduring classic. Her service to the society as President and as founding editor of EHB with Martin was instrumental in growing the Society and Journal from small beginnings to enduring institutions. -

Sibling Rivalry: Why the Nature/Nurture Debate Won't Go Away

Boston Globe 10/13/2002 Sibling rivalry Why the nature/nurture debate won't go away By Steven Pinker WHEN THE BRITISH EDUCATOR Richard Mulcaster wrote in 1582 that ''Nature makes the boy toward, nurture sees him forward,'' he gave the world a euphonious name for an opposition that has been debated ever since. People's beliefs about the roles of heredity and environment affect their opinions on an astonishing range of topics. Do adolescents engage in violence and substance abuse because of the way their parents treated them as toddlers? Are people inherently selfish and aggressive, which would justify a market economy and a strong police, or could they become peaceable and cooperative, allowing the state to wither and a spontaneous socialism to blossom? Is there a universal aesthetic that allows great art to transcend time and place, or are people's tastes determined by their era and culture? With so much at stake, it is no surprise that debates over nature and nurture evoke such strong feelings. Much of the heat comes from framing the issues as all-or-none dichotomies, and some of it can be transformed into light with a little nuance. Humans, of course, are not exclusively selfish or generous (or nasty or noble); they are driven by competing motives elicited in different circumstances. Although no aspect of the mind is unaffected by learning, the brain has to come equipped with complex neural circuitry to make that learning possible. And if genes affect behavior, it is not by pulling the strings of the muscles directly, but via their intricate effects on a growing brain. -

Exploitation, Exploration, and Financial Regulation

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES THE GORDON GEKKO EFFECT: THE ROLE OF CULTURE IN THE FINANCIAL INDUSTRY Andrew W. Lo Working Paper 21267 http://www.nber.org/papers/w21267 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 June 2015 I thank Tobias Adrian, Bev Hirtle, and Antoine Martin for inviting me to discuss this topic, and Tobias Adrian, Jayna Cummings, Leigh Hafrey, Hamid Mehran, Joe Langsam, Adair Morse, Antoinette Schoar and participants at the October 2014 FAR meeting and the May 2015 Consortium for Systemic Risk Analytics meeting for helpful comments and suggestions. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author only, and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of any institution or agency, any of their affiliates or employees, or any of the individuals acknowledged above. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. The author has disclosed a financial relationship of potential relevance for this research. Further information is available online at http://www.nber.org/papers/w21267.ack NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2015 by Andrew W. Lo. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. The Gordon Gekko Effect: The Role of Culture in the Financial Industry Andrew W.