Delaware National Coastal Special Resource Study and Environmental Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Historic Landmark Nomination New

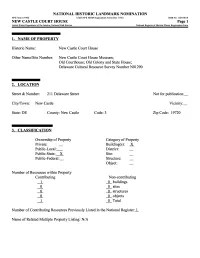

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 NEW CASTLE COURT HOUSE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: New Castle Court House Other Name/Site Number: New Castle Court House Museum; Old Courthouse; Old Colony and State House; Delaware Cultural Resource Survey Number NO 1290 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 211 Delaware Street Not for publication: City/Town: New Castle Vicinity:_ State: DE County: New Castle Code: 3 Zip Code: 19720 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: _ Building(s): JL Public-Local:__ District: _ Public-State:_X. Site: _ Public-Federal: Structure: _ Object: _ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Non-contributing 1 0 buildings 0 0 sites 0 0 structures 0 0 objects 1 0 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 1 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 NEW CASTLE COURT HOUSE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, N ational Park Service_____________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

161 F.Supp.2D 14

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA NATIONAL COALITION TO SAVE OUR MALL, et al., Plaintiffs, v. Civil Action 00-2371 (HHK) GALE NORTON, Secretary of the Interior, et al., Defendants. MEMORANDUM OPINION On May 25, 1993, Congress authorized the construction of a memorial in the District of Columbia to honor members of the Armed Forces who served during World War II and to commemorate the United States’ participation in that war. See Pub. L. 103-32, 107 Stat. 90, 91 (1993). The act empowered the American Battle Monuments Commission (“ABMC”), in connection with a newly-created World War II Memorial Advisory Board, to select a location for the WWII Memorial, develop its design, and raise private funds to support its construction. On October 25, 1994, Congress approved the location of the WWII Memorial in “Area 1” of the District, which generally encompasses the National Mall and adjacent federal land. See Pub. L. 103-422, 108 Stat. 4356 (1994). The ABMC reviewed seven potential sites within Area I and endorsed the Rainbow Pool site at the east end of the Reflecting Pool between the Lincoln Memorial and the Washington Monument as the final location for the WWII Memorial.1 Finally, 1 Out of the seven sites examined, the ABMC originally selected the Constitution Gardens area (between Constitution Avenue and the Rainbow Pool) as the location for the WWII Memorial, but later decided to endorse the present Rainbow Pool site. in May, 2001, Congress passed new legislation directing the expeditious construction of the WWII Memorial at the selected Rainbow Pool site. -

Workers' Hill Powder Yard Eleutherian Mills, the Du

VISITOR SERVICES WORKERS’ HILL ELEUTHERIAN MILLS, THE Where the du Pont story begins. Open daily from 9:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. The last bus for a DU PONT FAMILY HOME tour of the du Pont residence leaves at 3:30 p.m. Tickets Workers’ Hill is the remains of one of purchased after 2 p.m. are valid for the following day. several workers’ communities built by Eleutherian Mills, the first du Pont Closed on Thanksgiving and Christmas. the DuPont Company within walking home in America, was named for distance of the powder yards. its owner, Eleuthère Irénée du Pont. From January through mid-March, guided tours are He acquired the sixty-five-acre site The Gibbons House reflects the lives of the powder yard at 10:30 a.m. and 1:30 p.m. weekdays, with weekend in 1802 to build a gunpowder manufactory. The home foremen and their families. hours 9:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. today has furnishings and decorative arts that belonged Visitors with special needs should inquire at the Visitor The Brandywine Manufacturers’ Sunday School to his family and the generations that followed. Center concerning available services. illustrates early nineteenth-century education where E. I. du Pont’s restored French Garden is the beginning workers’ children learned to read and write. Contact any staff member for first aid assistance. of the du Pont family garden tradition in the The Belin House, where three generations of company Brandywine Valley. Several self-guided special tour leaflets are available at bookkeepers lived, is now the Belin House Organic Café. -

Social Studies Chapter 4, Lesson 1 Study Guide Name______Date______

Social Studies Chapter 4, Lesson 1 Study Guide Name_______________ Date___________ Key terms: Write the definition of each key term for Lesson 1. 1. Explorer-a person who travels to unfamiliar places in order to learn about them 2. Northwest Passage- a water route through North America to Asia (does not exist) 3. Trading Post-a store in a sparsely settled area where local people can barter (trade) products for goods 4. Colony-a place ruled by another country 5. Manufactured Goods- things that are manmade such as metal axes and cooking pots, and weapons Directions: Use the method, Who? What did he/she do? When? Where? and So What? to give the importance of each of the following people. The first has been done for you! 6. Henry Hudson- (Who?) Henry Hudson was an explorer (What did he/she do?) who was searching for a Northwest Passage (When?) in 1609 (Where) when he came upon the Delaware Bay. (So What?) He reported his findings to the rulers of European countries which caused them to send explorers to claim the land for their own. 7. Cornelius Hendrickson- was a Dutch Explorer from the Netherlands who came to the Delaware Bay in 1616. The Dutch set up two trading posts to trade with the Native Americans for beaver furs 8. Peter Minuit- A Dutch man hired by Sweden. In 1636 he bought land from the Native Americans to set up a colony for the Swedish named New Sweden. It is located near where Wilmington, DE is today. Swedish colonists and soldiers build Fort Christina, showing other countries that Sweden had some military power in the New World 9. -

VGP) Version 2/5/2009

Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) VESSEL GENERAL PERMIT FOR DISCHARGES INCIDENTAL TO THE NORMAL OPERATION OF VESSELS (VGP) AUTHORIZATION TO DISCHARGE UNDER THE NATIONAL POLLUTANT DISCHARGE ELIMINATION SYSTEM In compliance with the provisions of the Clean Water Act (CWA), as amended (33 U.S.C. 1251 et seq.), any owner or operator of a vessel being operated in a capacity as a means of transportation who: • Is eligible for permit coverage under Part 1.2; • If required by Part 1.5.1, submits a complete and accurate Notice of Intent (NOI) is authorized to discharge in accordance with the requirements of this permit. General effluent limits for all eligible vessels are given in Part 2. Further vessel class or type specific requirements are given in Part 5 for select vessels and apply in addition to any general effluent limits in Part 2. Specific requirements that apply in individual States and Indian Country Lands are found in Part 6. Definitions of permit-specific terms used in this permit are provided in Appendix A. This permit becomes effective on December 19, 2008 for all jurisdictions except Alaska and Hawaii. This permit and the authorization to discharge expire at midnight, December 19, 2013 i Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 William K. Honker, Acting Director Robert W. Varney, Water Quality Protection Division, EPA Region Regional Administrator, EPA Region 1 6 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, Barbara A. -

Recommendations for a Circa 1870-1885 Worker's Vegetable

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR A CIRCA 1870-1885 WORKER'S VEGETABLE GARDEN AT THE HAGLEY MUSEUM by Karen Marie Probst A non-thesis project submitted to the Fa~ulty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Horticultural Administration December 1987 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR A CIRCA 1870-1885 WORKER'S VEGETABLE GARDEN AT THE HAGLEY MUSEUM by Karen Marie Probst Approved: QpffM.1J tJ ~ 1iftLJt i ames E. Swasey, Ph.D. Professor In Charge Of on-Thesis Projects On Behalf Of The Advisory Committee Approved: ames E. Swasey, Ph.D. Coordinator of the Longw d Graduate Program in Public Horticulture Administration Approved: Richard B. Murray, Ph.D. Associate Provost for Graduate Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS page Project 1 Chapter 1 • INTRODUCTION. • • • • . • . • • • • • . • • . • . • . • • • • • • . • . 1 Footnotes. .. 11 2. RECOMMENDED VEGETABLES •••••.••••••••••.•••.••. 12 ASPARAGUS. • • • • • . • • . • • • . • • . • • . .• • 12 Footnotes. .. 16 BEAN. • • • . • • . • . • . .. 18 Footnotes . .-.. .. 34 BEET. • • . • . • • • . • • . • . • . • . • • • . .. 38 Footnotes........................... 46 CABBAGE. • • • • . • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • . • • • • • .. 48 Footnotes. .. 61 CARROT. • • • • • • . • • . • • . • • • . • • . • . • • . .. 64 Footnotes. .. 70 CELERY. • • • . • . • • . • . • . • . • . • . • • • . .. 72 Footnotes. .. 79 CORN. • . • • . • • • • • • • . • • • • . • . • • • • • • . • . .• 81 Footnotes. .. 87 CUCUMBER. • • . • . • . • • • • • • . • . • . .. 89 Footnotes. .. 94 LETTUCE. -

Leipsic River Watershed Proposed Tmdls

Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control Leipsic River Watershed Proposed TMDLs Arden Claymont Wilmington Bellefonte Newark New Castle Delaware City Odessa Middletown Smyrna Clayton 13 Leipsic Kenton Cheswold Dupont Manor Hartly Dover Little Creek Bowers Frederica Houston Harrington Slaughter Beach Greenwood Ellendale Milton Lewes Bridgeville Rehoboth Beach Millsboro Bethel Dagsboro Bethany Beach Frankford South Bethany Selbyville Fenwick Island DNRE007 August 2006 PREFACE The draft Proposed TMDLs for the Leipsic River watershed were reviewed during a public workshop held on 11 May, 2006. All comments received at the workshop and during the May 1 through 31 comment period were considered by DNREC. This report has been updated to address public comments by Mid-Atlantic Environmental Law Center (Sections 1.1, 2.0, 4.0, 4.2, 6.1, 6.4 and 6.5). i CONTENTS Section Page PREFACE...............................................................................................................................................................i CONTENTS .........................................................................................................................................................ii FIGURES..............................................................................................................................................................iii TABLES ................................................................................................................................................................iv -

Pencader Philadelphia Pike and Brandywine Valley Red Clay Mill and History Tour Stanton-Newark

TAL06082-Map3 8/14/06 10:00 AM Page 1 S d Rd R 82 r Valle yle w Rd k ve y P 491 W vie e a R ood e e r d C T B e C B G h C h r e a d a d o e d k e a m i p k y R k R R i m 1 p R 841 N P a ll P Brandywine e h s s e r i d Z N e b w r o e c d d u M d d o n b r e p R o O r R G o r Town Center l m R e h u i r e t R Flint t l Rd d e PHILADELPHIAg PIKE AND r e y s d t l l d l u l a R i h n d d d o d R M RED CLAY MILL AND HISTORY TOURR t h a n l n nt R g ti le K il ur g 261 R e l C B i e 796 B R i e d P C e l c d H n i r e h n M Woods l d r e r M i d tt C i b n k R t B R n a d n amsey E d s r M R e n h R tt Rd u l t d o G e nne B i d Ke 52 l h Old C s r y e m l r e e d R d 100 S Brandywine a B e Duration: Approximately 90 minutes r l l d 92 M n i a W N l Stat M Perry Park aa u e Rd d M w o Jester ma e S t i ff ns Bechtal l R T C d o R b t S l l u h R d d d e N il n d Park a t a School Park ta R S d e la R R l Marcus Balt S e M O l imore Pike Pennsylvania d g w G r d l d S S d BRANDYWINE VALLEY r O w d n d A 13 r K d s u k e d R e g R i b s h R t u n r l Hook R n i R v N e et F d d b R a n e e g v t d C M B R n a r n e n ente o u Harvey t e o i t d A r i R D i n t R k n e d g e r l P A r n u h Take a tour of the Red Clay Mill industry, powered k s y o 3 a e i g e e t d t a p k G y Mill Park u r p l e d 4.e. -

Principal Fortifications of the United States (1870–1875)

Principal Fortifications of the United States (1870–1875) uring the late 18th century and through much of the 19th century, army forts were constructed throughout the United States to defend the growing nation from a variety of threats, both perceived and real. Seventeen of these sites are depicted in a collection painted especially for Dthe U.S. Capitol by Seth Eastman. Born in 1808 in Brunswick, Maine, Eastman found expression for his artistic skills in a military career. After graduating from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, where offi cers-in-training were taught basic drawing and drafting techniques, Eastman was posted to forts in Wisconsin and Minnesota before returning to West Point as assistant teacher of drawing. Eastman also established himself as an accomplished landscape painter, and between 1836 and 1840, 17 of his oils were exhibited at the National Academy of Design in New York City. His election as an honorary member of the academy in 1838 further enhanced his status as an artist. Transferred to posts in Florida, Minnesota, and Texas in the 1840s, Eastman became interested in the Native Americans of these regions and made numerous sketches of the people and their customs. This experience prepared him for his next five years in Washington, D.C., where he was assigned to the commissioner of Indian Affairs and illus trated Henry Rowe Schoolcraft’s important six-volume Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States. During this time Eastman also assisted Captain Montgomery C. Meigs, superintendent of the Capitol Brevet Brigadier General Seth Eastman. -

Delaware Offshore Geologic Inventory 2001 to 2008

Executive Summary Episodic large storms and trends in long-term shoreline change continue to erode Delaware's beaches. To combat the erosion, beach nourishment is the preferred method for maintaining the Atlantic shoreline of Delaware for the purpose of protecting structures and infrastructure. State, local, and federal governments have contributed to the protection against coastal erosion. There were a number of government-sponsored beach fills between 1957 and 2005, and those amounted to emplacing 9,491,799 cubic yards at a cost of $23,960,001 (DNREC, 2005 spreadsheet). Most of the sand used for these projects came from upland sites and several areas offshore Delaware. As those sites become depleted, new sources of sand must be found. Over the past 18 years, the Delaware Geological Survey (DGS) has compiled a geologic database titled the Delaware Offshore Geologic Inventory (DOGI). This database contains information on the location of potential sand resources from state and federal waters for use in beach nourishment. The DGS has worked in partnership with the US Minerals Management Service (MMS) and the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control (DNREC) to determine the offshore geologic framework and to identify new sources of beach- quality sand. Also included in the DOGI are vibracores (cores) that were taken from offshore Delaware. The DGS maintains the state’s offshore core repository. This report represents a compilation of data that has been collected for the DOGI from 2001 to 2007 in partnership with MMS. During this time period, a total of 61 cores were collected in the Atlantic waters offshore Delaware for the purpose of determining potential borrow areas that could be used for beach nourishment. -

The Archaeology of 17Th-Century New Netherland Since1985: an Update Paul R

Northeast Historical Archaeology Volume 34 From the Netherlands to New Netherland: The Archaeology of the Dutch in the Old and New Article 6 Worlds 2005 The Archaeology of 17th-Century New Netherland Since1985: An Update Paul R. Huey Follow this and additional works at: http://orb.binghamton.edu/neha Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Huey, Paul R. (2005) "The Archaeology of 17th-Century New Netherland Since1985: An Update," Northeast Historical Archaeology: Vol. 34 34, Article 6. https://doi.org/10.22191/neha/vol34/iss1/6 Available at: http://orb.binghamton.edu/neha/vol34/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Northeast Historical Archaeology by an authorized editor of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. Northeast Historical Archaeology/Vol. 34,2005 95 The Archaeology of 17th-Century New Netherland Since 1985: An Update Paul R. Huey . In 1985, a number of goals and research questions were proposed in relation to the archaeology of' pre-1664 sites in the Dutch colony of New Netherland. Significant Dutch sites were subsequently ~xcavated in Albany, Kingston, and other places from 1986 through 1988, while a series of useful publications con tinued to be produced after 1988. Excavations at historic period Indian sites also continued after 1988 . Excavations in 17th-century sites from Maine to Maryland have revealed extensive trade contacts with New Netherland and the Dutch, while the Jamestown excavations have indicated the influence of the Dutch !n the early history of Virginia. -

UCLA SSIFI C ATI ON

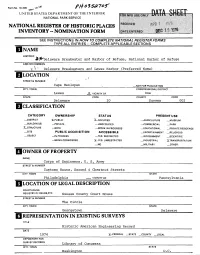

Form No. 10-300 ^ -\0-' W1 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ___________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS___________ ,NAME HISTORIC . .^ il-T^belaware Breakwater and Harbor of Refuge, National Harbor of Refuge AND/OR COMMON Y \k> Delaware Breakwaters and Lewes Harbor (Preferred Name) ________ LOCATION STREETS. NUMBER _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Lewes X VICINITY OF One STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Delaware 10 Sussex 002 UCLA SSIFI c ATI ON CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT X-PUBLIC X_OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK X_STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X-YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL -X-TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: Corps of Engineers, U. S. Army STREET & NUMBER Customs House, Second & Chestnut Streets CITY, TOWN STATE Philadelphia VICINITY OF Pennsylvania LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. Sussex County Court House STREET & NUMBER The Circle CITY, TOWN STATE Georgetown Delaware REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Engineering Record DATE 1974 X— FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress CITY, TOWN STATE Washington D,C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE X—EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED X_UNALTERED X-ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS —ALTERED —MOVED DATE_______ _FAIR — UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The breakwaters at Lewes reflect three stages of construction: the two-part original breakwater, the connection between these two parts, and the outer break water.