Kerala Society: Structure and Change (Soc4 E07)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Condition of Women in Pre-Modern Travancore

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH CULTURE SOCIETY ISSN: 2456-6683 Volume - 1, Issue - 6, Aug - 2017 CONDITION OF WOMEN IN PRE-MODERN TRAVANCORE Keerthana Santhosh Guest Faculty, Department of History, S N College, Chathannoor, India E mail – [email protected] Abstract: Travancore was the southernmost native state of British India and comprised the present day lands of the southern part of Kerala and Kanyakumari district of Tamil Nadu. It was a land of superstitions, untouchability, unseeability and unapproachability. Pragmatism and atheism were completely unknown there and people were extremely conservatives. It was a caste ridden society with Brahmanical dominance. Naturally, the condition of people belonging to the other castes, particularly lower castes was highly deplorable. But most pathetic was the condition of women. Not even a single section of women occupied a favorable position then. Even their existence was neglected. They were confined to the four walls of their own home. The study aims at the revealing of the condition of women in pre-modern Travancore. Key words: Travancore, Women, Sambandham, Smarthavicharam, Mannappedi, Pulappedi, Parappedi, Akathamma, Devadasi, Ezhuthupalli, Kalari, Kallumala. 1. INTRODUCTION: Women studies were a neglected field in the past. Only men were given importance. The word history itself seems to say his story and not her or their story. Most of the ancient books reveal the fact that they are the stories of men. We have Ramante Ayanam- Ramayanam as an example. As the title shows, it is just the journey of Rama – the protagonist and female characters are subsided. The ancient branch of knowledge, astrology also illustrates the point. -

Dress As a Tool of Empowerment : the Channar Revolt

Dress as a tool of Empowerment : The Channar Revolt Keerthana Santhosh Assistant Professor (Part time Research Scholar – Reg. No. 19122211082008) Department of History St. Mary’s College, Thoothukudi (Manonmanium Sundaranar sUniversity, Tirunelveli) Abstract Empowerment simply means strengthening of women. Travancore, an erstwhile princely state of modern Kerala was considered as a land of enlightened rulers. In the realm of women, condition of Travancore was not an exception. Women were considered as a weaker section and were brutally tortured.Patriarchy was the rule of the land. Many agitations occurred in Travancore for the upliftment of women. The most important among them was the Channar revolt, which revolves around women’s right to wear dress. The present paper analyses the significance of Channar Revolt in the then Kerala society. Keywords: Channar, Mulakkaram, Kuppayam 53 | P a g e Dress as a tool of Empowerment : The Channar Revolt Kerala is considered as the God’s own country. In the realm of human development, it leads India. Regarding women empowerment also, Kerala is a model. In women education, health indices etc. there are no parallels. But everything was not better in pre-modern Kerala. Women suffered a lot of issues. Even the right to dress properly was neglected to the women folk of Kerala. So what Kerala women had achieved today is a result of their continuous struggles. Women in Travancore, which was an erstwhile princely state of Kerala, irrespective of their caste and community suffered a lot of problems. The most pathetic thing was the issue of dress. Women of lower castes were not given the right to wear dress above their waist. -

Download Download

Volume 02 :: Issue 01 April 2021 A Global Journal ISSN 2639-4928 CASTE on Social Exclusion brandeis.edu/j-caste PERSPECTIVES ON EMANCIPATION EDITORIAL AND INTRODUCTION “I Can’t Breathe”: Perspectives on Emancipation from Caste Laurence Simon ARTICLES A Commentary on Ambedkar’s Posthumously Published Philosophy of Hinduism - Part II Rajesh Sampath Caste, The Origins of Our Discontents: A Historical Reflection on Two Cultures Ibrahim K. Sundiata Fracturing the Historical Continuity on Truth: Jotiba Phule in the Quest for Personhood of Shudras Snehashish Das Documenting a Caste: The Chakkiliyars in Colonial and Missionary Documents in India S. Gunasekaran Manual Scavenging in India: The Banality of an Everyday Crime Shiva Shankar and Kanthi Swaroop Hate Speech against Dalits on Social Media: Would a Penny Sparrow be Prosecuted in India for Online Hate Speech? Devanshu Sajlan Indian Media and Caste: of Politics, Portrayals and Beyond Pranjali Kureel ‘Ambedkar’s Constitution’: A Radical Phenomenon in Anti-Caste Discourse? Anurag Bhaskar, Bluestone Rising Scholar 2021 Award Caste-ing Space: Mapping the Dynamics of Untouchability in Rural Bihar, India Indulata Prasad, Bluestone Rising Scholar 2021 Award Caste, Reading-habits and the Incomplete Project of Indian Democracy Subro Saha, Bluestone Rising Scholar Honorable Mention 2021 Clearing of the Ground – Ambedkar’s Method of Reading Ankit Kawade, Bluestone Rising Scholar Honorable Mention 2021 Caste and Counselling Psychology in India: Dalit Perspectives in Theory and Practice Meena Sawariya, Bluestone Rising Scholar Honorable Mention 2021 FORUM Journey with Rural Identity and Linguicism Deepak Kumar Drawing on paper; 35x36 cm; Savi Sawarkar 35x36 cm; Savi on paper; Drawing CENTER FOR GLOBAL DEVELOPMENT + SUSTAINABILITY THE HELLER SCHOOL AT BRANDEIS UNIVERSITY CASTE A GLOBAL JOURNAL ON SOCIAL EXCLUSION PERSPECTIVES ON EMANCIPATION VOLUME 2, ISSUE 1 JOINT EDITORS-IN-CHIEF Laurence R. -

Autonomous Women's Movement in Kerala: Historiography Maya Subrahmanian

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 20 | Issue 2 Article 1 Jan-2019 Autonomous Women's Movement in Kerala: Historiography Maya Subrahmanian Follow this and additional works at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Subrahmanian, Maya (2019). Autonomous Women's Movement in Kerala: Historiography. Journal of International Women's Studies, 20(2), 1-10. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol20/iss2/1 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2019 Journal of International Women’s Studies. The Autonomous Women’s Movement in Kerala: Historiography By Maya Subrahmanian1 Abstract This paper traces the historical evolution of the women’s movement in the southernmost Indian state of Kerala and explores the related social contexts. It also compares the women’s movement in Kerala with its North Indian and international counterparts. An attempt is made to understand how feminist activities on the local level differ from the larger scenario with regard to their nature, causes, and success. Mainstream history writing has long neglected women’s history, just as women have been denied authority in the process of knowledge production. The Kerala Model and the politically triggered society of the state, with its strong Marxist party, alienated women and overlooked women’s work, according to feminist critique. -

List of Lacs with Local Body Segments (PDF

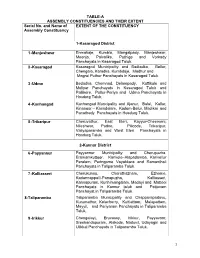

TABLE-A ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES AND THEIR EXTENT Serial No. and Name of EXTENT OF THE CONSTITUENCY Assembly Constituency 1-Kasaragod District 1 -Manjeshwar Enmakaje, Kumbla, Mangalpady, Manjeshwar, Meenja, Paivalike, Puthige and Vorkady Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 2 -Kasaragod Kasaragod Municipality and Badiadka, Bellur, Chengala, Karadka, Kumbdaje, Madhur and Mogral Puthur Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 3 -Udma Bedadka, Chemnad, Delampady, Kuttikole and Muliyar Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk and Pallikere, Pullur-Periya and Udma Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 4 -Kanhangad Kanhangad Muncipality and Ajanur, Balal, Kallar, Kinanoor – Karindalam, Kodom-Belur, Madikai and Panathady Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 5 -Trikaripur Cheruvathur, East Eleri, Kayyur-Cheemeni, Nileshwar, Padne, Pilicode, Trikaripur, Valiyaparamba and West Eleri Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 2-Kannur District 6 -Payyannur Payyannur Municipality and Cherupuzha, Eramamkuttoor, Kankole–Alapadamba, Karivellur Peralam, Peringome Vayakkara and Ramanthali Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 7 -Kalliasseri Cherukunnu, Cheruthazham, Ezhome, Kadannappalli-Panapuzha, Kalliasseri, Kannapuram, Kunhimangalam, Madayi and Mattool Panchayats in Kannur taluk and Pattuvam Panchayat in Taliparamba Taluk. 8-Taliparamba Taliparamba Municipality and Chapparapadavu, Kurumathur, Kolacherry, Kuttiattoor, Malapattam, Mayyil, and Pariyaram Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 9 -Irikkur Chengalayi, Eruvassy, Irikkur, Payyavoor, Sreekandapuram, Alakode, Naduvil, Udayagiri and Ulikkal Panchayats in Taliparamba -

Marxist Praxis: Communist Experience in Kerala: 1957-2011

MARXIST PRAXIS: COMMUNIST EXPERIENCE IN KERALA: 1957-2011 E.K. SANTHA DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SIKKIM UNIVERSITY GANGTOK-737102 November 2016 To my Amma & Achan... ACKNOWLEDGEMENT At the outset, let me express my deep gratitude to Dr. Vijay Kumar Thangellapali for his guidance and supervision of my thesis. I acknowledge the help rendered by the staff of various libraries- Archives on Contemporary History, Jawaharlal Nehru University, C. Achutha Menon Study and Research Centre, Appan Thampuran Smaraka Vayanasala, AKG Centre for Research and Studies, and C Unniraja Smaraka Library. I express my gratitude to the staff at The Hindu archives and Vibha in particular for her immense help. I express my gratitude to people – belong to various shades of the Left - who shared their experience that gave me a lot of insights. I also acknowledge my long association with my teachers at Sree Kerala Varma College, Thrissur and my friends there. I express my gratitude to my friends, Deep, Granthana, Kachyo, Manu, Noorbanu, Rajworshi and Samten for sharing their thoughts and for being with me in difficult times. I specially thank Ugen for his kindness and he was always there to help; and Biplove for taking the trouble of going through the draft intensely and giving valuable comments. I thank my friends in the M.A. History (batch 2015-17) and MPhil/PhD scholars at the History Department, S.U for the fun we had together, notwithstanding the generation gap. I express my deep gratitude to my mother P.B. -

Unit 10: Dalit Movement

Unit 10 Dalit Movement UNIT 10: DALIT MOVEMENT UNIT STRUCTURE 10.1 Learning Objectives 10.2 Introduction 10.3 Conceptualizing the term ‘Dalit’ 10.4 Dalit Movement: Emergence, Causes, Objectives 10.5 Dalit Movement: Issues, leadership and implications 10.6 Let Us Sum Up 10.7 Further Reading 10.8 Answers to Check Your Progress 10.9 Model Questions 10.1 LEARNING OBJECTIVES After going through this unit, you will be able to- l Obtain an overall understanding about the Dalit movement in India, l Know the primary causes, rise, issues, leadership and implications of the Dalit movement in India. 10.2 INTRODUCTION Social movements of different kinds and nature emerge due to issues and problems faced by the society. The Dalit movement emerged owing to specific social hurdles faced by particularly the so-called Dalit community of the country. In this unit, emphasis shall be laid on a holistic understanding of the idea of Dalit movements in India. 10.3 CONCEPTUALIZING THE TERM ‘DALIT’ The term “Dalit” is considered to have been derived from Sanskrit. The term in its simplest form implies “crushed”, or “broken to pieces”. Historically it is believed that the term was first used by Jyotirao Phule in the 19th century, in the milieu of the subjugation met by the former “untouchable” 116 Social Movements Dalit Movement Unit 10 castes among the Hindus. Mahatma Gandhi espoused the expression “Harijan,” (when loosely translated the term implies “Children of God”), to locate the former castaways. As per the Indian Constitution, the Dalits are the people who are listed in the schedule caste category. -

1. Introduction

1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. History Kasaragod, the northernmost district of Kerala, is endowed with rich natural resources and is noted for its majestic forts, ravishing rivers, hills, green valleys and beautiful beaches. The rich and varied cultural heritage of the district is portrayed through spectacular presentations of Theyyam, Yakshagana, Poorakkali, Kolkali and Mappilappattu. Seven languages are prevalent in Kasaragod. Malayalam is the administrative language. Other languages are Kannada, Tulu, Konkani, Marati, Urdu and Beary.Prior to State reorganization, Kasaragod was part of the South Kanara district.Kasaragod became a part of Malabar district following the reorganization of States and formation of unified Kerala State. Later, Kasaragod Taluk of Malabar district was bifurcated in to Kasaragod and Hosdurg Taluks and integrated with the then newly formed Cannanore district. Kasaragod became part of Kerala following the re-organization of states and formation of Kerala in 1st November 1956.The district was Kasaragod Taluk in Kannur District.The formation of Kasaragod district was a long felt ambition of the people.It is with the intention of bestowing maximum attention on the development of backward area, Kasaragod district was formed on 24th May,1984 as per GO (MS)No.520/84/RD, Dated 19.05.1984 by taking Kasaragod and Hosdurg taluks from the then Kannur district.The name Kasaragod is said to be derived from the word Kasaragod which means Nuxvemied Forest(Kanjirakuttam). 1.2. Physiography Kasaragod is bounded on the north and the east by Dakshina Kannada and Coorg districts of Karnataka State, on the south by Kannur district and on the west by the Lakshadweep Sea. -

List of Our Member Societies 'A' - Class Kozhencherry Taluk Sl.No

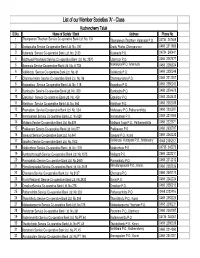

List of our Member Societies 'A' - Class Kozhencherry Taluk Sl.No. Name of Society / Bank Address Phone No. 1 Thumpamon Thazham Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 134 Thumpamon Thazham, Kulanada P.O. 04734 267609 2 Arattupuzha Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 787 Arattu Puzha, Chengannoor 0468 2317865 3 Kulanada Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 2133 Kulanada P.O. 04734 260441 4 Mezhuveli Panchayat Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 2570 Ullannoor P.O. 0468 2287477 5 Aranmula Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. A 703 Nalkalickal P.O. Aranmula 0468 2286324 6 Vallikkodu Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 61 Vallikkodu P.O. 0468 2350249 7 Chenneerkkara Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 96 Chenneerkkara P.O. 0468 2212307 8 Kaippattoor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 115 Kaipattoor P.O. 0468 2350242 9 Kumbazha Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 330 Kumbazha P.O. 0468 2334678 10 Elakolloor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 459 Elakolloor P.O. 0468 2342438 11 Elanthoor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 460 Elanthoor P.O. 0468 2362039 12 Pramadom Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 534 Mallassery P.O.,Pathanamthitta 0468 2335597 13 Naranganam Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.628 Naranganam P.O. 0468 2216506 14 Mylapra Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.639 Mailapra Town P.O., Pathanamthitta 0468 2222671 15 Prakkanam Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.677 Prakkanam P.O. 0468 2630787 16 Vakayar Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.847 Vakayar P.O., Konni 0468 2342232 17 Janatha Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.1042 Vallikkodu -Kottayam P.O., Mallassery 0468 2305212 18 Mekkozhoor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. -

Handbooks Kerala

district handbooks of kerala CANNANORE DIREtTORATE OF , roBLICRElATIONS DISTRICT HANDBOOKS OF KERALA CANNANORE DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC RELATIONS Sli). NaticBttl Systems VuiU Naiiori-I Institute of Educational Planning and A ministration 1 7 -B.StiAV V 'ndo CONTENTS Page 1. Short history of Cannanore 1 2. Topography and Climate 2 3. Religions 3 4 . Customs and Manners 6 5. Kalari 7 6. Industries 8 7. Animal Husbandry 9 8. Special Agricultural Development Unit 9 9. Fisheries 10 10. Communication and Transport 11 11. Education 11 12. Medical Facilities 11 13. Forests 12 14 , Professional and Technical Institutions 13 15. Religious Institutions 14 16 . Places of Interest 16 17 . District at a glance 21 18 . Blocks and Panchayats 22 PART I Cannanore is the anglicised form oF the Malayalam word “ Karinur” . According to one view “ Kannur” is the variation of Kanathur, an ancient village, the name of which survive even today in ont! of the wards of Canna nore MunicipaUty. Perhaps, like several other ancient towns of Kerala, Cannanore also is named after one of the deities of the Hindu Pantheon. Thus “ Kannur” is the compound of the two words ‘Kannan’ meaning Lord Kris;hna, and TJr’ meaning place, the place of Lord Krishna, Short history of Cannanore Cannanore, the northernmost district of Kerala State, is constituted of territories which formed part of the erst while district ol' Malabar and South Ganara, prior to the rc-organisation of the States in 1956. Cannanore district was formed on January 1, 1957 by trifurcating the erstwhile Malabar district of the former Madras State. The district has a distinct history of its own which is in many rcspects independent of the history of other regions oi the State. -

Ahtl-European STRUGGLE by the MAPPILAS of MALABAR 1498-1921 AD

AHTl-EUROPEAn STRUGGLE BY THE MAPPILAS OF MALABAR 1498-1921 AD THESIS SUBMITTED FDR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE DF Sactnr of pitilnsopliQ IN HISTORY BY Supervisor Co-supervisor PROF. TARIQ AHMAD DR. KUNHALI V. Centre of Advanced Study Professor Department of History Department of History Aligarh Muslim University University of Calicut Al.garh (INDIA) Kerala (INDIA) T6479 VEVICATEV TO MY FAMILY CONTENTS SUPERVISORS' CERTIFICATE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT LIST OF MAPS LIST OF APPENDICES ABBREVIATIONS Page No. INTRODUCTION 1-9 CHAPTER I ADVENT OF ISLAM IN KERALA 10-37 CHAPTER II ARAB TRADE BEFORE THE COMING OF THE PORTUGUESE 38-59 CHAPTER III ARRIVAL OF THE PORTUGUESE AND ITS IMPACT ON THE SOCIETY 60-103 CHAPTER IV THE STRUGGLE OF THE MAPPILAS AGAINST THE BRITISH RULE IN 19™ CENTURY 104-177 CHAPTER V THE KHILAFAT MOVEMENT 178-222 CONCLUSION 223-228 GLOSSARY 229-231 MAPS 232-238 BIBLIOGRAPHY 239-265 APPENDICES 266-304 CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH - 202 002, INDIA CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis "And - European Struggle by the Mappilas of Malabar 1498-1921 A.D." submitted for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Aligarh Muslim University, is a record of bonafide research carried out by Salahudheen O.P. under our supervision. No part of the thesis has been submitted for award of any degree before. Supervisor Co-Supervisor Prof. Tariq Ahmad Dr. Kunhali.V. Centre of Advanced Study Prof. Department of History Department of History University of Calicut A.M.U. Aligarh Kerala ACKNOWLEDGEMENT My earnest gratitude is due to many scholars teachers and friends for assisting me in this work. -

Page Front 1-12.Pmd

REPORT ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF KASARAGOD DISTRICT Dr. P. Prabakaran October, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS No. Topic Page No. Preface ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 PART-I LAW AND ORDER *(Already submitted in July 2012) ............................................ 9 PART - II DEVELOPMENT PERSPECTIVE 1. Background ....................................................................................................................................... 13 Development Sectors 2. Agriculture ................................................................................................................................................. 47 3. Animal Husbandry and Dairy Development.................................................................................. 113 4. Fisheries and Harbour Engineering................................................................................................... 133 5. Industries, Enterprises and Skill Development...............................................................................179 6. Tourism .................................................................................................................................................. 225 Physical Infrastructure 7. Power .................................................................................................................................................. 243 8. Improvement of Roads and Bridges in the district and development