Myanmar Update November 2017 Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B U R M a B U L L E T

B U R M A B U L L E T I N ∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞A month-in-review of events in Burma∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞ A L T E R N A T I V E A S E A N N E T W O R K O N B U R M A campaigns, advocacy & capacity-building for human rights & democracy Issue 20 August 2008 • Fearing a wave of demonstrations commemorating th IN THIS ISSUE the 20 anniversary of the nationwide uprising, the SPDC embarks on a massive crackdown on political KEY STORY activists. The regime arrests 71 activists, including 1 August crackdown eight NLD members, two elected MPs, and three 2 Activists arrested Buddhist monks. 2 Prison sentences • Despite the regime’s crackdown, students, workers, 3 Monks targeted and ordinary citizens across Burma carry out INSIDE BURMA peaceful demonstrations, activities, and acts of 3 8-8-8 Demonstrations defiance against the SPDC to commemorate 8-8-88. 4 Daw Aung San Suu Kyi 4 Cyclone Nargis aid • Daw Aung San Suu Kyi is allowed to meet with her 5 Cyclone camps close lawyer for the first time in five years. She also 5 SPDC aid windfall receives a visit from her doctor. Daw Suu is rumored 5 Floods to have started a hunger strike. 5 More trucks from China • UN Special Rapporteur on human rights in Burma HUMAN RIGHTS 5 Ojea Quintana goes to Burma Tomás Ojea Quintana makes his first visit to the 6 Rape of ethnic women country. The SPDC controls his meeting agenda and restricts his freedom of movement. -

Mm-Ami-Conference2015-Chitwin-Passing the Mace

AUSTRALIA MYANMAR INSTITUTE Passing the mace from the Myanmar’s first to the second legislature Chit Win 1/29/2016 When the five year term of the first legislature “Hluttaw” in Myanmar ends in January 2016, it will be remembered as a robust legislature acting as an opposition to the executive. The second legislature of Myanmar is set to be totally different from the first one in every aspect. This paper looks at three key defining features of the first legislature namely non-partisanship, the role of the Speakers and the relationship with the executive and how much of these would be embedded or changed when the mace of the first term of the Hluttaw is passed to the second. Contents 1. Introduction .........................................................................................2 2. Highlights of the first legislature ................................................................2 3. Non-Partisanship ...................................................................................4 4. The role of the Speakers ..........................................................................5 5. Relationship with the executive .................................................................6 6. Conclusion ...........................................................................................8 Annex 1 ...................................................................................................9 Annex 2 .................................................................................................10 !1 Passing the mace from -

Additional Agenda Item, Report of the Officers of the Governing Bodypdf

International Labour Conference Provisional Record 2-2 101st Session, Geneva, May–June 2012 Additional agenda item Report of the Officers of the Governing Body 1. At its 313th Session (March 2012), the Governing Body requested its Officers to undertake a mission (the “Mission”) to Myanmar and to report to the International Labour Conference at its 101st Session (2012) on all relevant issues, with a view to assisting the Conference’s consideration of a review of the measures previously adopted by the Conference 1 to secure compliance by Myanmar with the recommendations of the Commission of Inquiry that had been established to examine the observance by Myanmar of its obligation in respect of the Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No. 29). 2. The Mission, composed of Mr Greg Vines, Chairperson of the Governing Body, Mr Luc Cortebeeck, Worker Vice-Chairperson of the Governing Body, and Mr Brent Wilton, Secretary of the Employers’ group of the Governing Body, as the personal representative of Mr Daniel Funes de Rioja, the Employer Vice-Chairperson of the Governing Body, visited Myanmar from 1 to 5 May 2012. The Mission met with authorities at the highest level, including: the President of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar; the Speaker of the Parliament’s lower house; the Minister of Labour; the Minister of Foreign Affairs; the Attorney-General; other representatives of the Government; and the Commander-in-Chief of the Defence Services. It was also able to meet and discuss with Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, President of the National League for Democracy (NLD); representatives of other opposition political parties; the National Human Rights Commission; labour activists; the leaders of newly registered workers’ organizations; and employers’ representatives from the Union of Myanmar Federation of Chambers of Commerce and Industry (UMFCCI) and recently registered employers’ organizations. -

Women Arrested & Charged List

ARRESTS No. Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark S: 8 of the Export and Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD Import Law and S: 25 leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and of the Natural Superintendent Kyi President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Disaster Management Lin of Special Branch, 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and law, Penal Code - Dekkhina District regions were also detained. 505(B), S: 67 of the Administrator Telecommunications Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Chief Minister of Karen State President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 1-Feb-21 and 8- Detained in Hpa-An 2 (Daw) Nan Khin Htwe Myint F (Central Executive Committee Karen State chief ministers and ministers in the states and Feb-21 Prison Member of NLD) regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Telecommunications Ayeyarwady 3 Dr. Hla Myat Thway F Minister of Social Affairs 1-Feb-21 Detained chief ministers and ministers in the states and Law - 66(D) Region regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Minister of Karen Ethnic Affairs of Detained in Insein 4 Naw Pan Thinzar Myo F 1-Feb-21 Rangoon Region chief ministers and ministers in the states and Rangoon Region Government Prison regions were also detained. -

Myanmar Update May 2019 Report

STATUS OF HUMAN RIGHTS & SANCTIONS IN MYANMAR MAY 2019 REPORT Summary. This report reviews the May 2019 developments relating to human rights in Myanmar. Relatedly, it addresses the interchange between Myanmar’s reform efforts and the responses of the international community. I. Political Developments......................................................................................................2 A. Rohingya Refugee Crisis................................................................................................2 B. Corruption.......................................................................................................................2 C. International Community / Sanctions...........................................................................3 II. Civil and Political Rights...................................................................................................5 A. Freedom of Speech, Assembly and Association............................................................5 B. Freedom of the Press and Censorship...........................................................................5 III. Economic Development.....................................................................................................7 A. Economic Development—Legal Framework, Foreign Investment............................7 B. Economic Development—Infrastructure, Major Projects..........................................8 IV. Peace Talks and Ethnic Violence....................................................................................10 -

Democracy First, Federalism Next? the Constitutional Reform Process in Myanmar

ISSUE: 2019 No. 93 ISSN 2335-6677 RESEARCHERS AT ISEAS – YUSOF ISHAK INSTITUTE ANALYSE CURRENT EVENTS Singapore |8 November 2019 Democracy First, Federalism Next? The Constitutional Reform Process in Myanmar Nyi Nyi Kyaw* EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • The ruling National League for Democracy (NLD) party launched a process of constitutional amendment in February 2019, but without the support of the unelected military bloc that holds a quarter of the seats in Myanmar’s parliament, constitutional amendment remains impossible. • Whereas the NLD wants gradually to reduce the power of the military in politics, the military and its proxy Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) seek to increase that power or at least maintain the constitutional status quo. • Ethnic political parties have called for an immediate reduction of the power of the military and demanded more devolution of powers to ethnic states. They are unhappy with the NLD’s silence concerning federalism. • The politicking over constitutional amendment has made clear that these three groups — the NLD, the military and the USDP, and ethnic parties — will each go their own way to capitalize on the rift between them for gains in the general elections due in November 2020. * Nyi Nyi Kyaw is Visiting Fellow in the Myanmar Studies Programme of ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. 1 ISSUE: 2019 No. 93 ISSN 2335-6677 INTRODUCTION The increasingly controversial and heated topic confronting Myanmar is the 2008 Constitution of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar, under which the country’s political transition began in 2010. In the view of democrats or civilian politicians under the leadership of the ruling National League for Democracy (NLD) party and its chair State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, the constitution gives undue power to the military. -

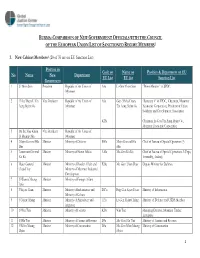

28 of 35 Are on EU Sanction List)

BURMA: COMPARISON OF NEW GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS WITH THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION LIST OF SANCTIONED REGIME MEMBERS1 1. New Cabinet Members2 (28 of 35 are on EU Sanction List) Position in Code on Name on Position & Department on EU No Name New Department EU List EU list Sanction List Government 1 U Thein Sein President Republic of the Union of A4a Lt-Gen Thein Sein “Prime Minister” of SPDC Myanmar 2 Thiha Thura U Tin Vice President Republic of the Union of A5a Gen (Thiha Thura) “Secretary 1” of SPDC, Chairman, Myanmar Aung Myint Oo Myanmar Tin Aung Myint Oo Economic Corporation, President of Union Solidarity and Development Association K23a Chairman, Lt-Gen Tin Aung Myint Oo, Myanmar Economic Corporation 3 Dr. Sai Mao Kham Vice President Republic of the Union of @ Maung Ohn Myanmar 4 Major General Hla Minister Ministry of Defense B10a Major General Hla Chief of Bureau of Special Operation (3) Min Min 5 Lieutenant General Minister Ministry of Home Affairs A10a Maj-Gen Ko Ko Chief of Bureau of Special Operations 3 (Pegu, Ko Ko Irrawaddy, Arakan). 6 Major General Minister Ministry of Border Affairs and E28a Maj-Gen Thein Htay Deputy Minister for Defence Thein Htay Ministry of Myanmar Industrial Development 7 U Wunna Maung Minister Ministry of Foreign Affairs Lwin 8 U Kyaw Hsan Minister Ministry of Information and D17a Brig-Gen Kyaw Hsan Ministry of Information Ministry of Culture 9 U Myint Hlaing Minister Ministry of Agriculture and 115a Lt-Gen Myint Hlaing Ministry of Defence and USDA Member Irrigation 10 U Win Tun Minister Ministry -

ASEAN and Political Change in Myanmar: Towards a Regional Initiative?

Contemporary Southeast Asia Vol. 30, No. 3 (2008), pp. 351-78 DOI: 10.1355/cs30-3a © 2008 ISEAS ISSN 0219-797X print / ISSN 1793-284X electronic ASEAN and Political Change in Myanmar: Towards a Regional Initiative? JÜRGEN HAACKE ASEAN states have favoured diplomacy and peer pressure in order to sway Myanmar's military regime to release Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and other political detainees and to promote national reconciliation. So far, ASEAN's combined efforts have not been very successful, although the generals are moving Myanmar beyond extra- constitutional rule. This paper asks whether, in the aftermath of the September 2007 protests, the constitutional referendum and Cyclone Nargis, there is much scope for a new regional effort to promote reconciliation and democratization in Myanmar that is additional to the support ASEAN offers for the good offices of the United Nations Secretary General. The paper sets out different positions held within ASEAN on promoting political change in Myanmar. It also examines the prospects for putting into practice recent ideas to address Myanmar's political situation in new regional settings. The paper concludes that: (1) significant difference characterize the Myanmar policy of individual ASEAN countries in line with varying interests and pressures, and dissimilar views on what — if anything — should be done to help Myanmar democratize; (2) Indonesia is the only ASEAN country to have conceptualized a possible regional diplomatic initiative, but its full implementation and success are far from certain. Keywords: Myanmar, ASEAN, national reconciliation, Jakarta Initiative on Myanmar, Cyclone Nargis, AIPMC. JÜRGEN HAACKE is a Senior Lecturer at the London School of Economics and Political Science, United Kingdom. -

COMMON POSITION 2009/615/CFSP of 13 August 2009 Amending Common Position 2006/318/CFSP Renewing Restrictive Measures Against Burma/Myanmar

L 210/38 EN Official Journal of the European Union 14.8.2009 III (Acts adopted under the EU Treaty) ACTS ADOPTED UNDER TITLE V OF THE EU TREATY COUNCIL COMMON POSITION 2009/615/CFSP of 13 August 2009 amending Common Position 2006/318/CFSP renewing restrictive measures against Burma/Myanmar THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, (5) Moreover, the Council considers it necessary to amend the lists of persons and entities subject to the restrictive Having regard to the Treaty on European Union, and in measures in order to extend the assets freeze to enter particular Article 15 thereof, prises that are owned or controlled by members of the regime in Burma/Myanmar or by persons or entities associated with them, Whereas: HAS ADOPTED THIS COMMON POSITION: (1) On 27 April 2006, the Council adopted Common Article 1 Position 2006/318/CFSP renewing restrictive measures against Burma/Myanmar ( 1). Annexes II and III to Common Position 2006/318/CFSP shall be replaced by the texts of Annexes I and II to this Common Position. (2) Council Common Position 2009/351/CFSP ( 2) of 27 April 2009 extended until 30 April 2010 the Article 2 restrictive measures imposed by Common Position 2006/318/CFSP. This Common Position shall take effect on the date of its adoption. (3) On 11 August 2009, the European Union condemned Article 3 the verdict against Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and This Common Position shall be published in the Official Journal announced that it will respond with additional targeted of the European Union. restrictive measures. -

CHAPTER7 Myanmar's Security Outlook and the Myanmar Defence Services

CHAPTER 7 Myanmar’s Security Outlook and the Myanmar Defence Services Tin Maung Maung Than Introduction: Elected civilian government and the military in politics There were expressions of disappointment and even outright condemnation by the West and opposition groups that viewed the 7 November 2010 elections, held under the auspices of the ruling State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), as neither free nor fair as well as lacking inclusiveness. Allegations of votes being manipulated in favour of the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP that was transformed from the military-sponsored Union Solidarity and Development Organization, led by former prime minister and retired general U Thein Sein), the boycott of National League for Democracy (NLD, which convincingly won the 1990 election and whose leader Nobel laureate Daw Aung San Suu Kyi was still under house arrest had refused to re-register for competing in the polls) and complaints of unfair election laws tarnished the victory of the USDP which won overwhelmingly. By winning over 79 percent of the contested seats in the Pyithu Hluttaw (People’s Assembly or lower house of parliament) and nearly 77 percent in the Amyotha Hluttaw (National Assembly or upper house of parliament) at the national level and substantially (majority party in all seven states and seven regions) at the provincial level, the USDP was in a position to form the Union Government as well as the respective Region/State Governments. Though the Chairman of the SPDC Senior General Than Shwe and the Vice Chairman -

Chronology of Burma's Constitutional Process

Chronology of Burma’s Constitutional Process February 12, 1947: While Burma is still under British colonial rule, the Panglong Agreement is signed by Burmese leader General Aung San and several ethnic nationality leaders from the Shan, Kachin, and Chin areas. The agreement is designed to hasten independence from the British and avert ethnic tensions in the new Burma, as recognized in paragraph 7 that states, “Citizens of the Frontier Areas shall enjoy rights and privileges which are regarded as fundamental in democratic societies.” July 19, 1947: General Aung San and several members of the cabinet are assassinated in Rangoon. U Nu and his Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL) prepare to take power from the British by finishing Burma’s first constitution. January 4, 1948: Burma gains independence from British rule and institutes the 1947 constitution. The new constitution and its federal structure included the Shan state, Karenni state, Kachin state, and Karen state, with the Chin Hills being classified as a “special division.” The constitution granted the right of secession to special division states after 10 years (chapter 10, articles 201-206) subject to a majority vote in the state assembly and majority in a plebiscite. March 2, 1962: The military Revolutionary Council under General Ne Win overthrows the constitutionally elected civilian government. December 15-31, 1973: The Revolutionary Council conducts a referendum to endorse the new constitution, which is carried by over 90 percent of the vote in a process that many international observers do not assess as fair. March 1974: Burma’s second constitution is implemented, transferring power from the Revolutionary Council to the Burma Socialist Program Party (BSPP). -

General Assembly Distr

UNITED NATIONS A General Assembly Distr. GENERAL A/51/466 8 October 1996 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH Fifty-first session Agenda item 110 (c) HUMAN RIGHTS QUESTIONS: HUMAN RIGHTS SITUATIONS AND REPORTS OF SPECIAL RAPPORTEURS AND REPRESENTATIVES Situation of human rights in Myanmar Note by the Secretary-General The Secretary-General has the honour to transmit to the members of the General Assembly the interim report on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, prepared by Judge Rajsoomer Lallah, Special Rapporteur of the Commission on Human Rights, in accordance with Commission resolution 1996/80 of 23 April 1996. 96-27373 (E) 071196 /... A/51/466 English Page 2 CONTENTS Paragraphs Page I. INTRODUCTION ......................................... 1 - 11 3 II. THE INTERNATIONAL NORMS GOVERNING HUMAN RIGHTS ....... 12 - 15 6 III. BASIC LEGAL FRAMEWORK GOVERNING THE EXERCISE OF POLITICAL RIGHTS IN MYANMAR .......................... 16 - 34 7 A. The establishment of the State Law and Order Council and the imposition of martial law ........ 17 - 20 7 B. The general elections of May 1990 ................ 21 - 22 8 C. Declaration No. 1/1990 and the National Convention 23 - 29 9 D. Non-conformity of the legal framework with international norms .............................. 30 - 33 11 E. Remedial measures for the re-establishment of constitutionality and the democratic order ....... 34 12 IV. IMPACT OF MYANMAR LAW ON HUMAN RIGHTS ................ 35 - 145 12 A. Extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions ... 37 - 42 13 B. Torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment ........................................ 43 - 51 14 C. Arbitrary arrest and detention ................... 52 - 61 15 D. Due process and the rule of law .................. 62 - 71 17 E.