Nine Poems, Followed by Democracyand Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alan Seeger: Medievalism As an Alternative Ideology

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by K-State Research Exchange This is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript as accepted for publication. The publisher-formatted version may be available through the publisher’s web site or your institution’s library. Alan Seeger: medievalism as an alternative ideology Tim Dayton How to cite this manuscript If you make reference to this version of the manuscript, use the following information: Dayton, T. (2012). Alan Seeger: Medievalism as an alternative ideology. Retrieved from http://krex.ksu.edu Published Version Information Citation: Dayton, T. (2012). Alan Seeger: Medievalism as an alternative ideology. First World War Studies, 3(2), 125-144. Copyright: © 2012 Taylor & Francis Digital Object Identifier (DOI): doi:10.1080/19475020.2012.728698 Publisher’s Link: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/19475020.2012.728698 This item was retrieved from the K-State Research Exchange (K-REx), the institutional repository of Kansas State University. K-REx is available at http://krex.ksu.edu 0 Alan Seeger: Medievalism as an Alternative Ideology Tim Dayton* Department of English Kansas State University Manhattan, KS USA 66502 * E-mail: [email protected]; Tel. 785-532-2155 1 Alan Seeger: Medievalism as an Alternative Ideology Abstract The American poet Alan Seeger imagined the First World War as an opportunity to realize medieval values, which were embodied for him in Sir Philip Sidney. Sidney epitomized Seeger’s three ideals: “Love and Arms and Song,” which contrasted with the materialism and sophistication of modernity. His embrace of “Arms” and the desire for intense, authentic experience led Seeger, who was living in Paris in August 1914, to enlist in the French Foreign Legion, in which he served until his death in combat in July 1916. -

Howard Willard Cook, Our Poets of Today

MODERN AMERICAN WRITERS OUR POETS OF TODAY Our Poets of Today BY HOWARD WILLARD COOK NEW YORK MOFFAT, YARD & COMPANY 1919 COPYRIGHT, 1918, BY MOFFAT, YARP & COMPANY C77I I count myself in nothing else so happy as in a soul remembering my good friends: JULIA ELLSWORTH FORD WITTER BYNNER KAHLIL GIBRAN PERCY MACKAYE 4405 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To our American poets, to the publishers and editors of the various periodicals and books from whose pages the quotations in this work are taken, I wish to give my sincere thanks for their interest and co-operation in making this book possible. To the following publishers I am obliged for the privilege of using selections which appear, under their copyright, and from which I have quoted in full or in part: The Macmillan Company: The Chinese Nightingale, The Congo and Other Poems and General Booth Enters Heaven by Vachel Lindsay, Love Songs by Sara Teasdale, The Road to Cas- taly by Alice Brown, The New Poetry and Anthology by Harriet Monroe and Alice Corbin Henderson, Songs and Satires, Spoon River Anthology and Toward the Gulf by Edgar Lee Masters, The Man Against the Sky and Merlin by Edwin Arlington Rob- inson, Poems by Percy MacKaye and Tendencies in Modern American Poetry by Am> Lowell. Messrs. Henry Holt and Company: Chicago Poems by Carl Sandburg, These Times by Louis Untermeyer, A Boy's Will, North of Boston and Mountain Interval by Robert Frost, The Old Road to Paradise by Margaret Widdener, My Ireland by Francis Carlin, and Outcasts in Beulah Land by Roy Helton. Messrs. -

The Republican Journal the News of Belfast

The Republican Journai. 88 i'OI.rME MARCH 1916. "BELFAST, MAINE, THURSDAY, 23, NUMBER 1 g' j»u«««.. of todays d° Contents City Government utmo®‘ to guard against 1 a fine Organized. I tt!fir voice, and for many yean sang in the members end his loss overdraft?* won,d call theatten- OBITUARY. will be felt keenly. For Comments. .The War tf^w.» } “Pecwl'y * choir of the Universalist v >w.Paner ■tr«®t and aide walk church, of which he some time his PERSONAL. of *£.e department!! ti — only son, Eugene G. Pierce, hss 1 Government Organized^. Mayor’s Address, Appointment Com- Hs? °S “f News.FCdty 5“ 0Terdr»fta and ask that whet waa a very liberal supporter and earnest been associsted ; Situation. .Obituary.. etc. with him, under the firm name ht? Mexican mittees, Inoney or bo that oil £ ^eir expended, nearly worker. For years he taught a large class of E. C. Pitcher of East Belfast. 8“Ch C. Pierce & Co. He is survived his Ralph Caribou is in Belfast on personal The members*elect of the “ *' need f°r pub,i< of by .The News c;ty council met young men in the Sunday school. Of a a business. shington Whisperings. safety be'auapeade'l wife, by son, E. G. Pierce, a daughter, Mrs. Waldo Pomona 10 a. m., March 20th, and were called to very nature the church was for Brooks. North my view* on Bume o: spiritual him Mary Eck, and a I. L. th!£pVmfV*giVe,L-3L0U by brother, George G. Pierce, Perry returned last Saturday from & f Rev J. -

Download Download

e Mission stateMent Elements, the undergraduate research journal of Boston College, showcases the varied research endeavors of fellow undergraduates to the greater academic community. By fostering intellectual curiosity and discussion, the journal strengthens and affirms the community of undergraduate students at Boston College. thanks eleMents staff editor’s note We would like to thank Boston College, the Institute for the Liberal Editor-in-chiEf Text goes here.Rio. Occulpa volorem rectemquo illuptate earuptaspit eium Apici omnis estio tecus alit, velibus solore ium quam doluptatur sit volo- Arts, and the Office of the Dean for the College of Arts and Sciences Emily Simon dollaccum sit, con res reptum as es conserum nis suntore ndundae ssusdae rumquam voluptam quam, nem sim quae la nonesti orrunt eum in con for the financial support that makes this issue possible. cum ut facest, qui te dolupti atiure, ommolesecae doluptaquias inis et dese- conecabo. Lum, torempo rporibus ella doluptatasit ent dem net optate per- managing Editor qua sperentiam nem. Ita doluptatur ad mod maximporrunt reius pero ea chil landiat unt. Questions & Contributions Brandon BaviEr debis ut aut renihictin necaerum fuga. Itatur aut quas es dolum rehendan- dae nobis aut etur, ium andis re, consediae pelland erchicto quia que corio- Necte ma voluptus. Nestem. Por moluptia que omnisque si blander entor- If you have any questions, please contact the journal at Deputy Editor ratus ea non comnien ihillam excesen imetur sit raerescia parcienisto do- porem volorer iosapis dolora volorem. Et as dolore, cone ideleniminum rei- [email protected]. The next deadline is Tuesday, November, 20, 2012. Eric tracz lum, as vererum et volore pos evel in etusani simpore officatem. -

Imperialism and Progressivism

001-016 878503-0 5/5/07 10:37 AM Page 13 Name Date Class #######American Literature Readings 3 # # # # # Imperialism and Progressivism INTRODUCTION 3 At the beginning of the 1900s, new and growing industries offered the American people more opportunities than ever before. Under the surface of this growth and prosperity, however, the United States faced serious problems. The cities were growing too fast to UNIT maintain decent housing and services for their populations. Few laws regulated working conditions in the factories. Writers began to use their words to expose political corruption and social evils. When the Great War broke out in Europe in 1914, President Woodrow Wilson asked Americans to remain “neutral in fact as well as in name.” Eventually, neutrality remained impossible. In 1917 American troops entered World War I, one of the bloodiest conflicts in world history. from The Battle With the Slum Jacob A. Riis # About the Selection Jacob A. Riis (1849–1914) immigrated to the United States from Denmark when he was 21 years old. Living in New York City, Riis recognized the cycle of poverty and its effects on the home and community. When he became a newspaper reporter, he drew attention to the fight for social improvement, and his most famous book, How the Other Half Lives, actually led to reforms in tenement housing. In The Battle With the Slum (1902), Riis warns about the effects of not helping the impoverished. raw-Hill Companies, Inc. raw-Hill GUIDED READING As you read, note how Riis compares the slum to an enemy that must be conquered. -

Pete Seeger: a Singer of Folk Songs

LINGUACULTURE 2, 2020 PETE SEEGER: A SINGER OF FOLK SONGS DAVID LIVINGSTONE Palacký University Abstract Pete Seeger would have turned one hundred and one on May 3 of this year. To commemorate these ten decades plus one year, I would like to look at eleven of the most remarkable aspects of Pete Seeger’s life, work and legacy. This paper will examine the cultural impact and oral tradition of the music, songs and books of Pete Seeger. This legendary folk musician's career spanned eight decades and touched on many of the key historical developments of the day. He is responsible for some of the iconic songs which have not only helped define American culture, but even beyond. Seeger was also a pioneer in a number of fields, using his music to propagate political convictions, ecological themes, civil rights, world music, education, etc. The folk singer also had his finger on the pulse of a number of developments in American history and culture. He was friends with a number of prominent musicians and artists and influenced an entire range of younger musicians and activists. Keywords: Pete Seeger; Folk music; American history; Social activism; Civil Rights movement Family Pete Seeger’ family was a powerhouse of talent, musically and beyond. Charles Seeger (1886-1979), his father, was a renowned musicologist who held a number of prominent university positions. His political convictions, obviously on the left, were also instrumental in forming his son’s ideological worldview. His mother Constance de Clyver (1886-1975) was also a musician although not as accomplished by far as his stepmother Ruth Seeger (1901-1953) (mother to Mike and Peggy). -

Grave Negotiations: the Rhetorical Foundations of American

GRAVE NEGOTIATIONS: THE RHETORICAL FOUNDATIONS OF AMERICAN WORLD WAR I CEMETERIES IN EUROPE by David W. Seitz Bachelor of Arts, Johns Hopkins University, 2002 Master of Arts, Johns Hopkins University, 2005 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2011 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by David W. Seitz It was defended on May 17, 2011 and approved by Dr. Neepa Majumdar, Associate Professor, Department of English Dr. Brenton Malin, Assistant Professor, Department of Communication Dr. Gordon Mitchell, Associate Professor, Department of Communication Dr. Kirk Savage, Professor, Department of History of Art and Architecture Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Ronald J. Zboray, Professor, Department of Communication ii Copyright © by David W. Seitz 2011 iii GRAVE NEGOTIATIONS: THE RHETORICAL FOUNDATIONS OF AMERICAN WORLD WAR I CEMETERIES IN EUROPE David W. Seitz, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2011 This dissertation uncovers the processes of negotiation between private citizens, President Woodrow Wilson’s administration, the War Department, and the Commission of Fine Arts that led to the establishment and final visual presentation of the United States permanent World War I cemeteries in Europe (sites that are still frequented by tens of thousands of international visitors each year). It employs archival research and the analysis of newspapers and photographs to recover the voices of the many stakeholders involved in the cemeteries’ foundation. Whereas previous studies have attempted to understand American World War I commemoration practices by focusing on postwar rituals of remembrance alone, my study contextualizes and explains postwar commemoration by analyzing the political ideologies, public rhetoric, and material realities of the war years (1914-1918)—ideologies, rhetoric, and material realities that shaped official and vernacular projects of memory after the Armistice. -

Alan Seeger Poetry Page

POEMS FOR REMBRANCE DAY, NOVEMBER 11 Rendezvous by Alan Seeger I have a rendezvous with Death At some disputed barricade, When Spring comes back with rustling shade And apple-blossoms fill the air – I have a rendezvous with Death When Spring brings back blue days and fair. It may be he shall take my hand And lead me into his dark land And close my eyes and quench my breath – It may be I shall pass him still. I have a rendezvous with Death On some scarred slope of battered hill, When Spring comes round again this year And the first meadow-flowers appear. God knows 'twere better to be deep Pillowed in silk and scented down, Where love throbs out in blissful sleep, Pulse nigh to pulse, and breath to breath, Where hushed awakenings are dear . But I've a rendezvous with Death At midnight in some flaming town, When Spring trips north again this year, And I to my pledged word am true, Alan Seeger (1886-1916) I shall not fail that rendezvous. Age 22 Alan Seeger (1888 - 1916) was an American poet who fought and died in World War I serving in the French Foreign Legion. A statue to his memory and to the memory of his comrades, Americans who had volunteered to fight for France, was erected in the Place des États-Unis, Paris. He was contemporary with poet T.S. Eliot. His brother Charles Seeger, a noted musicologist, was the father of the American folk singer, Pete Seeger. Alan Seeger entered Harvard in 1906, graduating in 1910. -

Download a Form, Sign It, and Submit It As a Scan Electronically, Or Mail It Back

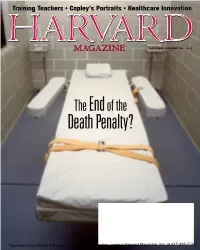

Training Teachers • Copley’s Portraits • Healthcare Innovation NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 2016 • $4.95 The End of the Death Penalty? Reprinted from Harvard Magazine. For more information, contact Harvard Magazine, Inc. at 617-495-5746 Hammond Cambridge is now RE/MAX Leading Edge Two Brattle Square | Cambridge, MA 617•497•4400 | CambridgeRealEstate.us CAMBRIDGE—Harvard Square. Two-bedroom SOMERVILLE—Ball Square. Gorgeous, renovated, BELMONT—Belmont Hill. 1936 updated Colonial. corner unit with a wall of south facing windows. 3-bed, 2.5-bath, 3-level, 1,920-square-foot town Period architectural detail. 4 bedroom. 2.5 Private balcony with views of the Charles. 24-hour house. Granite, stainless steel kitchen, 2-zone central bathrooms. C/A, 2-car garage. Private yard with concierge.. .............................................................. $1,200,000 AC, gas heat, W&D in unit, 2-car parking. ...$699,000 mature plantings. ...........................................$1,100,000 BELMONT—Lovely 1920s 9-room Colonial. 4 beds, BELMONT—Oversized, 2000+ sq. ft. house, 5 CAMBRIDGE—Delightful Boston views from private 2 baths. 2011 kitchen and bath. Period details. bedrooms, 2 baths, expansive deeded yard, newer balcony! Sunny and sparkling, 1-bedroom, upgraded Lovely yard, 2-car garage. Near schools and public gas heat and roof, off street parking. Convenient condo. Luxury amenities including 24-hour concierge, transportation. ................................................ $925,000 to train, bus to Harvard, and shops. .....$675,000 gym, pool, garage. -

The Pragmatics of Romance in the First World War' Poetry

AWEJ for Translation & Literary Studies, Volume3, Number4. October 2019 Pp. 61-85 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.24093/awejtls/vol3no4.6 The Pragmatics of Romance in the First World War' Poetry Jinan Kadhim Isma'eel English Department, College of Education for Women University of Baghdad. Iraq Rufaidah Kamal Abdulmajeed English Department, College of Education for Women University of Baghdad. Iraq Abstract Many influences have shaped literature; war is one of them. Among the horrors, death tolls, destructions, and chaos, there should be inevitably a beam of light of hope, a desirous and eagerness for long life, expressions of love, loyalty to the homeland and other feelings that carry a sense of romance in different shapes. This study hypothesized that romance is found in war poetry, and it has various meanings other than the conventional definition; the scope of the meanings of the word romance is either expanded or shrunk. The expansion happens throughout the appearance of new meanings. They were not there before or after this time. The shrinking happens when some of the meanings are vanished and no longer used as a denotation of romance. These meanings are realized in various pragmatic devices. The war poems selected for this study are Rupert Brooke's The Soldiers and Allan Seeger's I Have a Rendezvous with Death. The results show that romance has (34) meanings. Of them, is 'Idealization' and 'heroism'; which score the highest frequency and appear (5) times equal to (31%); 'Love and intimacy' comes next with (3) times equal to (19%); 'Bravery' scores (2) times equal to (13%); and finally 'Patriotism' registers the lowest frequency with (1) time, equal to (6%). -

April 1917 543 Cass Street, Chicago

VOL. X NO. I APRIL 1917 My People Carl Sandburg 1 Loam—The Year—Chicago Poet—Street Window— Adelaide Crapsey—Repetitions—Throw Roses—Fire- logs — Baby Face — Moon — Alix — Gargoyle — Prairie Waters—Moon-set—Wireless—Tall Grass—Bringers The Reawakening—Two Epitaphs . Walter de la Mare 12 Prussians Don't Believe in Dreams—To a French Aviator Fallen in Battle . Morris Gilbert 14 Out of Mexico . Grace Hazard Conkling 18 Velardeña Sunset—Santa Maria del Rio—The Museum —Gulf View—Spring Day—Patio Scene The Fugitive—The Crowning Gift . Gladys Cromwell 21 Easter Evening .... James Church Alvord 23 A Woman—The Stranger—To an Old Couple Scudder Middleton 24 Praise—To— William Saphier 26 Toadstools Alfred Kreymborg 27 Love Was Dead—Lanes—Again—Courtship—Sir Hob bledehoy—1914—Dirge Editorial Comment 32 The City and the Tower—Verner von Heidenstam Reviews . 38 Our Contemporaries—Correspondence—Notes . SO Copyright 1917 by Harriet Monroe. All rights reserved 543 CASS STREET, CHICAGO $1.50 PER YEAR SINGLE NUMBERS, 15 CENTS Published monthly by Ralph Fletcher Seymour, 1025 Fine Arts Building, Chicago. Entered as second-class matter at Postoffice, Chicago. , VOL. X No. I APRIL 1917 MY PEOPLE MY people are gray, pigeon gray, dawn gray, storm gray. I call them beautiful, and I wonder where they are going. LOAM In the loam we sleep, In the cool moist loam, To the lull of years that pass And the break of stars, From the loam, then, The soft warm loam, We rise: To shape of rose leaf, Of face and shoulder. [1] POETRY: A Magazine of Verse We stand, then, To a whiff of life, Lifted to the silver of the sun Over and out of the loam A day. -

Pete Seeger Dead: Folk Singer and Activist Dies at 94

The weather conditions are not available. change weather location News Sports Music Radio TV My Region More Watch Listen Search SeaSrcighn Up | Log In IN THE NEWS ■ Liberal senators ■ Data privacy World ■ Rob Ford ■ Stephen Hawking CBC News Home World Canada Politics Business Health Arts & Entertainment Technology & Science Community Weather Video World Photo Galleries Pete Seeger dead: folk singer and activist dies at 94 Seeger became famous as a member of The Weavers quartet, formed in 1948 The Associated Press Posted: Jan 28, 2014 1:54 AM ET | Last Updated: Jan 29, 2014 6:14 PM ET Stay Connected with CBC News Mobile Facebook Podcasts Twitter Alerts Newsletter American troubadour, folk singer and activist Pete Seeger died Monday Jan. 27, 2014, at age 94. Here, Seeger Must Watch performs on stage during the 2013 Farm Aid concert in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. Here's a look at his life in pictures. (Hans Pennink/The Associated Press) 1 of 11 Pete Seeger, the banjo-picking troubadour who sang for migrant 'They crucified me:' Ads for 'the drunk guy in workers, college students and star-struck presidents in a career that Ukrainian protester the back of the room' introduced generations of Americans to their folk music heritage, died (graphic images) 5:53 Monday at the age of 94. 3:25 Super Bowl ad review Pete Seeger dies at 94 2:28 Seeger's grandson, Kitama Cahill-Jackson said his grandfather died at Dmytro Bulatov says he and a primer on the was kidnapped on Jan. theory and practice of New York Presbyterian Hospital, where he'd been for six days.