The Scientific Path of Jakub Frostig in the Light of His Correspondence With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Context Study for the Hawaii State Hospital DAGS Job No

Context Study for the Hawaii State Hospital Prepared for the Department of Health Contracted by the Department of Accounting and General Services DAGS Job No. 12-20-2701 Prepared by: Mason Architects, Inc. February 2018 Table of Contents Project Team ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 Statement of Project Objectives and Background ............................................................................................... 1 Methodology ....................................................................................................................................................... 2 Historical Overview............................................................................................................................................. 3 Building Survey ................................................................................................................................................. 27 Architectural Types ........................................................................................................................................... 33 Historic Evaluation ............................................................................................................................................ 38 Bibliography ...................................................................................................................................................... 40 Appendices ....................................................................................................................................................... -

Mypogiycaefrtc THERAPY H R PSYCHOSES. Aajnfer S N Iie S , M . B . , O I, B . (G Ia S .), D. P .M .''E Ng-.}

MYPOGIYCAEfrTC THERAPY H R PSYCHOSES. by aajnfER sn iiE S , m .b . o, i, b . ( G ia s .) , d .p .m .''Eng-.} ProQuest Number: 13905515 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13905515 Published by ProQuest LLC(2019). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 CONTENTS. Introduction ............. v . ,......... , . I The selection of patients .............. 2. The method ........... 5. The duration of the treatment . 6, Phenomena during the treatment (A) Psychic phenomena . 7. (B) Physical phenomena 7. The significance of epileptic f i t s ................. II. Types of reaction to insulin . ................... I2a The interruption of the Iwpoglycaemia ....... IS. The complications of the treatment ........... 15. The indications for interruption ••••••••.. 18. Modifications in the technique <, ................. 19. The rationale of the treatment ............... 21. Other uses of hypoglycaemic treatment ......... 23b The case-re ports '.............. 34. Results in the present series 74. General discussion ............................. -75. Conclusions ..................... '.......... • 82. Appendix A ( on Cardiazol ) ............ 83. Appendix B ( instructions to nursing staff ) .... 85. References....................... 92. Introduction. in this paper an attempt is made to evaluate the so-called Insulin Shock treatment of schizophrenia, the-opin-o ions expressed being based on experience with eighteen female psychotics, and on a survey of the literature. -

Eighty Years of Electroconvulsive Therapy in Croatia and in Sestre Milosrdnice University Hospital Centre

Acta Clin Croat 2020; 59:489-495 Review doi: 10.20471/acc.2020.59.03.13 EIGHTY YEARS OF ELECTROCONVULSIVE THERAPY IN CROATIA AND IN SESTRE MILOSRDNICE UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL CENTRE Dalibor Karlović1,2,3, Vivian Andrea Badžim1, Marinko Vučić4, Helena Krolo Videka4, Ana Horvat4, Vjekoslav Peitl1,3, Ante Silić1,3, Branka Vidrih1,3, Branka Aukst-Margetić1,3, Danijel Crnković1,2,3 and Iva Ivančić Ravlić1,2,3 1Department of Psychiatry, Sestre milosrdnice University Hospital Centre, Zagreb, Croatia; 2School of Dental Medicine, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia; 3Catholic University of Croatia, Zagreb, Croatia; 4Department of Anesthesiology, Intensive Care and Pain Therapy, Sestre milosrdnice University Hospital Centre, Zagreb, Croatia Summary – In 1937, Ugo Cerletti and Lucio Bini performed electroconvulsive treatment (ECT) in Rome for the first time. That was the time when different types of ‘shock therapy’ were performed; beside ECT, insulin therapies, cardiazol shock therapy, etc. were also performed. In 1938, Cerletti and Bini reported the results of ECT. Since then, this method has spread rapidly to a large number of countries. As early as 1940, just two years after the results of the ECT had been published, it was also introduced in Croatia, at Sestre milosrdnice Hospital, for the first time in our hospital and in the then state of Yugoslavia. Since 1960, again the first in Croatia and the state, we performed ECT in general anesthesia and continued it down to the present, with a single time brake. Key words: Electroconvulsive therapy; General anesthesia; History; Hospital; Croatia General History of Electroconvulsive Therapy used since the 1930s. The first such therapy was the aforementioned insulin therapy, which was introduced Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is one of the old- in clinical practice in 1933 by the Austrian psychiatrist est methods of treatment in psychiatry, which was first Manfred Sakel. -

Joseph Wortis Collection at the Oskar Diethelm Library )

THE JOSEPH WORTIS COLLECTION AT THE OSKAR DIETHELM LIBRARY ) A GUIDE TO ACCESS Compiled by Laura Peimer & Jessica Silver The Winthrop Group, Inc. ) Information & Archival Services Division November, 1996 I . Provenance The Estate of Joseph Wortis, M.D. gave the personal papers of Joseph Wortis, M.D. which comprise the Joseph Wortis Collection, to the Oskar Diethelm Library in 1995. Henry Havelock Wortis, M.D., Joseph Wortis' son and the Executor of the Estate, signed the Deed of Gift in 1996. ) 1 ~) II. Biographical Sketch - Dr. Joseph Wortis (1906-1995) Joseph Wortis was born in Brooklyn, New York on October 2, 1906, one of five children of a Russian watchmaker and a French Alsatian mother. He attended New York University, where he majored in English literature before switching to a pre-medical course, and graduated in 1927 . 1 Soon after graduation, Wortis travelled to Europe. Instead of returning to the United States to attend Yale University Medical School in the Fall, he spent the next five years studying medicine at the University of Vienna, Medical Faculty (1927-1932), and in Munich and Paris. Upon returning to the United States, Wortis became a resident in Psychiatry at Bellevue Hospital, where he remained for less than a year. Havelock Ellis, the famous writer and sexologist whom he had met while on summer vacation in England in 1927, wrote asking if Wortis would accept a generous fellowship to return to Europe to study problems in the area of homosexuality. 2 Wortis accepted. Mrs. A. Kingsley Porter funded the fellowship. Broad in its mandate, the fellowship allowed Wortis to first develop his skills and training in psychiatry, with the expectation that he would later turn his attention to sex research. -

The Development of Electroconvulsive Therapy

Sound Neuroscience: An Undergraduate Neuroscience Journal Volume 1 Article 18 Issue 1 Historical Perspectives in Neuroscience 5-29-2013 The evelopmeD nt of Electroconvulsive Therapy Deborah J. Sevigny-Resetco University of Puget Sound, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/soundneuroscience Part of the Neuroscience and Neurobiology Commons Recommended Citation Sevigny-Resetco, Deborah J. (2013) "The eD velopment of Electroconvulsive Therapy," Sound Neuroscience: An Undergraduate Neuroscience Journal: Vol. 1: Iss. 1, Article 18. Available at: http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/soundneuroscience/vol1/iss1/18 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at Sound Ideas. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sound Neuroscience: An Undergraduate Neuroscience Journal by an authorized administrator of Sound Ideas. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sevigny-Resetco: The Development of Electroconvulsive Therapy The Development of Electroconvulsive Therapy Deborah Sevigny-Resetco Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), otherwise referred to as electroshock therapy, was first utilized as a treatment for schizophrenia in 1938 and its use has been surrounded by controversy ever since [1]. From the time this somatic therapy was introduced, it has been continually commended and criticized by both the scientific community and society as a whole. This paper will trace ECT from its origins in Rome to its integration in the United States; evaluating its development, as well as the contributions and the conflicts that accompanied it [2]. The brief history of ECT is as riveting as is it disconcerting; it is filled times of both rapid progress and stagnation. The effectiveness of ECT is evident in its success as a viable medical treatment however; simultaneously the implications of its misuse cannot be ignored. -

Electroconvulsive Therapy (Ect): Yes, We Really Still Do That!

Wisconsin Public Psychiatry Network Teleconference (WPPNT) • This teleconference is brought to you by the Wisconsin Department of Health Services (DHS), Division of Care and Treatment Services, Bureau of Prevention Treatment and Recovery and the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Department of Psychiatry. • Use of information contained in this presentation may require express authority from a third party. • 2021, Michael J Peterson, reproduced with permission. WPPNT Reminders How to join the Zoom webinar • Online: https://dhswi.zoom.us/j/82980742956(link is external) • Phone: 301-715-8592 – Enter the Webinar ID: 829 8074 2956#. – Press # again to join. (There is no participant ID) Reminders for participants • Join online or by phone by 11 a.m. Central and wait for the host to start the webinar. Your camera and audio/microphone are disabled. • Download or view the presentation materials. The evaluation survey opens at 11:59 a.m. the day of the presentation. • Ask questions to the presenter(s) in the Zoom Q&A window. Each presenter will decide when to address questions. People who join by phone cannot ask questions. • Use Zoom chat to communicate with the WPPNT coordinator or to share information related to the presentation. • Participate live or view the recording to earn continuing education hours (CEHs). Complete the evaluation survey within two weeks of the live presentation and confirmation of your CEH will be returned by email. • A link to the video recording of the presentation is posted within four business days of the presentation. • Presentation materials, evaluations, and video recordings are on the WPPNT webpage: https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/wppnt/2021.htm. -

Exam # 2 Study Guide Chapters 4, 9 & 15 Mental Status a Set of Interview Questions and Observations Designed to Reveal

PSYC 306 1st Edition Exam # 2 Study Guide Chapters 4, 9 & 15 Mental Status A set of interview questions and observations designed to reveal the degree and nature of a person’s abnormal functioning. ECT (Electroconvulsive Therapy) Used frequently because its an effective and fast acting intervention for unipolar o 60-80% of patients improve 1917 Malaria- Induced fever o Julius Wagner-Jauregg, Vienna 1927 Insulin- Induced Coma o Manfred Sakel, Berlin . Insulin injection . Seizures . Inject glucose 1934 Metrazol- Induced Coma o Ladislaus von Meduna, Budapest . Biological antagonism . 42% of spinal fractures First seen in the 1930’s … widespread use by 1939 o 1937- Ugo Cerlitti & Lucio Bini o Nominated for noble prize . ECT Procedure Informed consent Anesthetic Muscle relaxant 800 milliamps Several hundred watts 1-6 seconds 3X/ week 6-12 treatments Texas does 1500 annually o Age range (16-97) o Although effective it has declined since the 1950’s . B/c of memory loss associated with treatment & The frightening nature of the procedure Behavioral Treatment Rational-Emotive Therapy (RET) o Cognitive therapy o Developed by Albert Ellis o Help people identify and change the irrational assumptions and thinking that help cause psychological disorders Stress Inoculation Training o SIT Stages . Conceptualization phase . Rehearsal phase . Application phase Re-hospitalizations decrease by 50% among clients treated with cognitive- behavioral therapy Anti-Depressants 1st Generation o Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAO) /tricyclics . Marplan . Nardil 2nd Generation o Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRI’s) . Group of 2nd generation anti-depressant drugs that increase serotonin activity specifically without affecting other neurotransmitters Prozac (Most popular) o ‘Reach for Mother’s Little Helper” . -

Cardiazol Treatment in British Mental Hospitals Niall Mccrae

‘A violent thunderstorm’: Cardiazol treatment in British mental hospitals Niall Mccrae To cite this version: Niall Mccrae. ‘A violent thunderstorm’: Cardiazol treatment in British mental hospitals. History of Psychiatry, SAGE Publications, 2006, 17 (1), pp.67-90. 10.1177/0957154X06061723. hal-00570852 HAL Id: hal-00570852 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00570852 Submitted on 1 Mar 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. HPY 17(1) McCrae 1/23/06 4:16 PM Page 1 History of Psychiatry, 17(1): 067–090 Copyright © 2006 SAGE Publications (London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi) www.sagepublications.com [200603] DOI: 10.1177/0957154X06061723 ‘A violent thunderstorm’: Cardiazol treatment in British mental hospitals NIALL MCCRAE* Institute of Psychiatry, London In the annals of psychiatric treatment, the advent of Cardiazol therapy has been afforded merely passing mention as a stepping-stone to the development of electroconvulsive therapy. Yet in the 1930s it was the most widely used of the major somatic treatment innovations in Britain’s public mental hospitals, where its relative simplicity and safety gave it preference over the elaborate and hazardous insulin coma procedure. -

The Evolution of Restraint in American Psychiatry

Yale University EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library School of Medicine January 2017 The volutE ion Of Restraint In American Psychiatry Danilo Alejandro Rojas-Velasquez Yale University Follow this and additional works at: https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ymtdl Recommended Citation Rojas-Velasquez, Danilo Alejandro, "The vE olution Of Restraint In American Psychiatry" (2017). Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library. 2167. https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ymtdl/2167 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Medicine at EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library by an authorized administrator of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EVOLUTION OF RESTRAINT IN AMERICAN PSYCHIATRY A Thesis Submitted to the Yale University School of Medicine in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Medicine by Danilo Rojas-Velasquez 2017 CONTENTS ABSTRACT ………………………………………………………………………. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ………………………………………………………….iv INTRODUCTION ………………………………………………………………….1 CHAPTER 1: FROM MADHOUSE TO ASYLUM ……………………………… 9 CHAPTER 2: SOMATIC TREATMENTS AND PSYCHOSURGERY ………… 33 CHAPTER 3: THE BIOLOGICAL ERA ………………………………………… 51 CONCLUSION ……………………………………………………………………. 68 APPENDIX A ………………………………………………………………………72 APPENDIX B ………………………………………………………………………78 -

Lessons from the History of Somatic Treatments from the 1900S to the 1950S

Mental Health Services Research, Vol. 1, No. 4, 1999 History and Evidence-Based Medicine: Lessons from the History of Somatic Treatments from the 1900s to the 1950s Joel T. Braslow1 This paper examines the early history of biological treatments for severe mental illness. Focusing on the period of the 1900s to the 1950s, I assess the everyday use of somatic therapies and the science that justified these practices. My assessment is based upon patient records from state hospitals and the contemporaneous scientific literature. I analyze the following somatic interventions: hydrotherapy, sterilization, malaria fever therapy, shock therapies, and lobotomy. Though these treatments were introduced before the method of randomized controlled trials, they were based upon legitimate contemporary science (two were Nobel Prize-winning interventions). Furthermore, the physicians who used these inter- ventions believed that they effectively treated their psychiatric patients. This history illustrates that what determines acceptable science and clinical practice was and, most likely will, continue to be dependent upon time and place. I conclude with how this history sheds light on present-day, evidence-based medicine. KEY WORDS: evidence-based medicine; history of psychiatry; somatic therapies; biological psychiatry. INTRODUCTION measured up to the new scientific standards. These facts have led us to view these pre-RCT therapies Over the last couple of decades, researchers, cli- and the doctors who used them as mired in a pre- nicians, and policy-makers have urged clinicians to scientific age, where personal conviction, local con- base their practices upon scientific evidence, the most text, and social and cultural values played as large a robust of this evidence being the randomized con- role as science in the care and treatment of patients. -

Biographical Register

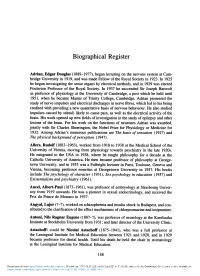

Biographical Register Adrian, Edgar Douglas (1889-1977), began lecturing on the nervous system at Cam- bridge University in 1919, and was made Fellow of the Royal Society in 1923. In 1925 he began investigating the sense organs by electrical methods, and in 1929 was elected Foulerton Professor of the Royal Society. In 1937 he succeeded Sir Joseph Barcroft as professor of physiology at the University of Cambridge, a post which he held until 1951, when he became Master of Trinity College, Cambridge. Adrian pioneered the study of nerve impulses and electrical discharges in nerve fibres, which led to his being credited with providing a new quantitative basis of nervous behaviour. He also studied impulses caused by stimuli likely to cause pain, as well as the electrical activity of the brain. His work opened up new fields of investigation in the study of epilepsy and other lesions of the brain. For his work on the functions of neurones Adrian was awarded, jointly with Sir Charles Sherrington, the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for 1932. Among Adrian's numerous publications are The basis of sensation (1927) and The physical background ofperception (1947). Aliers, Rudolf (1883-1963), worked from 1918 to 1938 at the Medical School of the University of Vienna, moving from physiology towards psychiatry in the late 1920s. He emigrated to the USA in 1938, where he taught philosophy for a decade at the Catholic University of America. He then became professor of philosophy at George- town University, and in 1955 was a Fulbright lecturer in Paris, Toulouse, Geneva and Vienna, becoming professor emeritus at Georgetown University in 1957. -

Psychiatric Tourists in Pre-War Europe: the Visits of Reg Ellery and Aubrey Lewis

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health - Papers: part A Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health 1-1-2015 Psychiatric tourists in pre-war Europe: the visits of Reg Ellery and Aubrey Lewis Robert M. Kaplan University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/smhpapers Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Kaplan, Robert M., "Psychiatric tourists in pre-war Europe: the visits of Reg Ellery and Aubrey Lewis" (2015). Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health - Papers: part A. 3616. https://ro.uow.edu.au/smhpapers/3616 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Psychiatric tourists in pre-war Europe: the visits of Reg Ellery and Aubrey Lewis Abstract After 1936, psychiatry in Europe was going through a turbulent phase. The new physical treatments heralded a long-awaited breakthrough. However, political developments seriously affected the practice of psychiatry in Germany, Austria and the Soviet Union; in other countries, the situation was little better. It was widely recognised that a new war was looming. At this time, their trips almost overlapping, two psychiatrists did an extensive tour of European facilities. One was the prominent Maudsley psychiatrist Aubrey Lewis; the other was Reg Ellery, largely unknown outside his native Melbourne. The reports of both men were, for various reasons, ignored until recently. This paper looks at the trip taken by the two psychiatrists and their different perspectives on what they found.