Coordination and Policy Traps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christian Hellwig

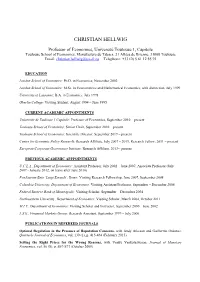

CHRISTIAN HELLWIG Professeur Associé d’Economie, Université Toulouse 1, Capitole Toulouse School of Economics, Manufacture de Tabacs, 21 Allées de Brienne, 31000 Toulouse Email: [email protected] Telephone: +33 (0) 5 61 12 85 93 EDUCATION Ph.D. in Economics, London School of Economics, November 2002 M.Sc. in Econometrics and Mathematical Economics, with distinction, London School of Economics, July 1999 B.A. in Economics, University of Lausanne, July 1998 Visiting Student, Oberlin College, August 1994 – June 1995 CURRENT ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Professeur Associé, Université de Toulouse 1 Capitole, September 2010 – present Member, Toulouse School of Economics, September 2010 – present Member, Institut d’Economie Industrielle, September 2010 – present Research Affiliate, Centre for Economic Policy Research, July 2007 – present ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE Associate Professor (with tenure), Department of Economics, UCLA, July 2007 – present (on leave 2010-11) Assistant Professor, Department of Economics, UCLA, July 2002 – June 2007 Visiting Research Fellowship, Fondazione Ente ‘Luigi Einaudi’, Rome, June 2007, September 2008 Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of Economics, Columbia University, September – December 2006 Visiting Scholar, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, September – December 2004 Visiting Scholar, Department of Economics, Northwestern University, March 2004 Visiting Scholar and Instructor, Department of Economics, MIT, September 2000 – June 2002 Research Assistant, Financial Markets Group, LSE, September 1999 – July 2000 PUBLICATIONS IN REFEREED JOURNALS Setting the Right Prices for the Wrong Reasons, with Venky Venkateswaran, Journal of Monetary Economics, vol. 56 (S), p. S57-S77 (October 2009) Bubbles and Self-enforcing Debt, with Guido Lorenzoni, Econometrica, vol. 77 (4), p. 1137-1164 (July 2009) Knowing What Others Know: Coordination Motives in Information Acquisition, with Laura Veldkamp, Review of Economic Studies, vol. -

Crises and Prices: Information Aggregation, Multiplicity, and Volatility

Crises and Prices: Information Aggregation, Multiplicity, and Volatility By GEORGE-MARIOS ANGELETOS AND IVA´ N WERNING* Crises are volatile times when endogenous sources of information are closely monitored. We study the role of information in crises by introducing a financial market in a coordination game with imperfect information. The asset price aggre- gates dispersed private information acting as a public noisy signal. In contrast to the case with exogenous information, our main result is that uniqueness may not obtain as a perturbation from perfect information: multiplicity is ensured with small noise. In addition, we show that: (a) multiplicity may emerge in the financial price itself; (b) less noise may contribute toward nonfundamental volatility even when the equilibrium is unique; and (c) similar results obtain for a model where individuals observe one another’s actions, highlighting the importance of endogenous infor- mation more generally. (JEL D53, D82, D83) It’s a love-hate relationship—economists are outcomes, but often lack obvious comparable at once fascinated and uncomfortable with mul- changes in fundamentals. Many attribute an im- tiple equilibria. On the one hand, crises can be portant role to more or less arbitrary shifts in described as times of high nonfundamental vol- “market sentiments” or “animal spirits,” and atility: they involve large and abrupt changes in models with multiple equilibria formalize these ideas.1 On the other hand, these models can also be viewed as incomplete theories, which should * Angeletos: Department of Economics, Massachusetts ultimately be extended along some dimension Institute of Technology, 50 Memorial Drive, Cambridge, MA 02142, and National Bureau of Economic Research to resolve the indeterminacy. -

Transparency of Information and Coordination in Economies with Investment Complementarities

ISSUES IN MACROECONOMIC POLICY DESIGN Transparency of Information and Coordination in Economies with Investment Complementarities By GEORGE-MARIOS ANGELETOS AND ALESSANDRO PAVAN* Economies with production externalities, de- spect to public information, which increases the mand spillovers, incomplete financial markets, volatility generated by common noise in market and Keynesian frictions are only a few exam- expectations. Moreover, when information is ples of those in which macroeconomic comple- heterogeneous, an increase in the precision of mentarities play a prominent role. Within this public information may have the perverse effect class of economies, how does the precision of of increasing aggregate volatility, by increasing publicly provided and privately collected infor- the sensitivity of economic activity to common mation affect equilibrium allocations and social noise. On the contrary, an increase in the pre- welfare? And what is the optimal transparency cision of private information necessarily re- in the information conveyed, for example, by duces aggregate volatility. Nevertheless, we economic statistics, policy announcements, or show that, as long as there is no value to lotter- news in the media? To answer these questions, ies, welfare unambiguously increases with an we consider a simple real economy where the increase in either the relative or the absolute individual return to investment is increasing in precision of public information. Hence, policies the aggregate level of investment and where that either disseminate more precise informa- market participants have heterogenous expecta- tion about economic fundamentals or reduce the tions about the underlying economic fundamen- heterogeneous interpretation of economic statis- tals (the exogenous productivity). We interpret tics and policy measures necessarily boost wel- an increase in the transparency of public infor- fare. -

Signaling in a Global Game: Coordination and Policy Traps

Signaling in a Global Game: Coordination and Policy Traps George-Marios Angeletos Massachusetts Institute of Technology and National Bureau of Economic Research Christian Hellwig University of California, Los Angeles Alessandro Pavan Northwestern University This paper introduces signaling in a global game so as to examine the informational role of policy in coordination environments such as currency crises and bank runs. While exogenous asymmetric in- formation has been shown to select a unique equilibrium, we show that the endogenous information generated by policy interventions leads to multiple equilibria. The policy maker is thus trapped into a We are grateful to the editor, Nancy Stokey, and two anonymous referees for suggestions that greatly helped us improve the paper. For comments we thank Daron Acemoglu, Andy Atkeson, Philippe Bacchetta, Gadi Barlevy, Marco Bassetto, Olivier Blanchard, Ricardo Caballero, V. V. Chari, Eddie Dekel, Glenn Ellison, Paul Heidhues, Patrick Kehoe, Robert Lucas Jr., Narayana Kocherlakota, Kiminori Matsuyama, Stephen Morris, Bala`zs Szentes, Jean Tirole, Muhamet Yildiz, Iva´n Werning, and seminar participants at Athens University of Economics and Business, Berkeley, Carnegie-Mellon, Harvard, Iowa, Lausanne, London School of Economics, Mannheim, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Northwestern, Stanford, Stony Brook, Toulouse, University of California at Los Angeles, University of Pennsylvania, the Federal Reserve Banks of Boston, Cleveland, and Minneapolis, the 2002 annual meeting of the Society for Economic Dynamics, the 2002 Universita´PompeuFabra workshop on coordination games, the 2003 Centre for Economic Policy Research Euro- pean Summer Symposium in International Macroeconomics, and the 2003 workshop of the Stanford Institute for Theoretical Economics. We also thank Emily Gallagher for excellent editing assistance. -

Transparency of Information and Coordination in Economies with Investment Complementarities

ISSUES IN MACROECONOMIC POLICY DESIGN Transparency of Information and Coordination in Economies with Investment Complementarities By GEORGE-MARIOS ANGELETOS AND ALESSANDRO PAVAN* Economies with production externalities, de- spect to public information, which increases the mand spillovers, incomplete financial markets, volatility generated by common noise in market and Keynesian frictions are only a few exam- expectations. Moreover, when information is ples of those in which macroeconomic comple- heterogeneous, an increase in the precision of mentarities play a prominent role. Within this public information may have the perverse effect class of economies, how does the precision of of increasing aggregate volatility, by increasing publicly provided and privately collected infor- the sensitivity of economic activity to common mation affect equilibrium allocations and social noise. On the contrary, an increase in the pre- welfare? And what is the optimal transparency cision of private information necessarily re- in the information conveyed, for example, by duces aggregate volatility. Nevertheless, we economic statistics, policy announcements, or show that, as long as there is no value to lotter- news in the media? To answer these questions, ies, welfare unambiguously increases with an we consider a simple real economy where the increase in either the relative or the absolute individual return to investment is increasing in precision of public information. Hence, policies the aggregate level of investment and where that either disseminate more precise informa- market participants have heterogenous expecta- tion about economic fundamentals or reduce the tions about the underlying economic fundamen- heterogeneous interpretation of economic statis- tals (the exogenous productivity). We interpret tics and policy measures necessarily boost wel- an increase in the transparency of public infor- fare. -

Defense Policies Against Currency Attacks: on the Possibility of Predictions in a Global Game with Multiple Equilibria

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Angeletos, George-Marios; Hellwig, Christian; Pavan, Alessandro Working Paper Defense policies against currency attacks: on the possibility of predictions in a global game with multiple equilibria Discussion Paper, No. 1459 Provided in Cooperation with: Kellogg School of Management - Center for Mathematical Studies in Economics and Management Science, Northwestern University Suggested Citation: Angeletos, George-Marios; Hellwig, Christian; Pavan, Alessandro (2007) : Defense policies against currency attacks: on the possibility of predictions in a global game with multiple equilibria, Discussion Paper, No. 1459, Northwestern University, Kellogg School of Management, Center for Mathematical Studies in Economics and Management Science, Evanston, IL This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/31181 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

Ph.D. in ECONOMICS GAME THEORY

Ph.D. in ECONOMICS GAME THEORY (2020) Prof. Mario Gilli PURPOSE: This course is an introduction to topics in game theory. Its objective is to equip the students with tools, which are essential to study economics of information and of strategic behaviour and for setting up and solving a wide range of economic problems. COURSE DESCRIPTION: The course consists of six lectures. We start with game representations. First, a game tree is defined, as well as information sets and pure, mixed and behavioral strategies, perfect recall and Kuhn’s theorem, complete as well as incomplete information. Then we consider Strategic form games and the relation among different ways of modelling strategic Interaction. Thus, properties and calculation of solutions and of Nash equilibria are discussed. Next Nash equilibria in extensive form games are analysed and refinements proposed. Finally, we turn to the analysis of dynamic games with incomplete information. STRUCTURE: The lectures will illustrate the main concepts through formal definitions and examples, with a particular attention to the calculus of solutions. There will be problem sets as homework. You are encouraged to form small group to solve problem sets. The problems will be quite difficult: you are not expected to be able to answer all the questions correctly. In the final part of the course, the students will present in groups research papers to the class. The aim is to learn how to read and understand research topics, in order to prepare the final dissertation. Your course grade will be based on the homework (20%), on the group presentation (20%) and on the final exam (60%). -

Nber Working Paper Series Information Manipulation

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES INFORMATION MANIPULATION, COORDINATION, AND REGIME CHANGE Chris Edmond Working Paper 17395 http://www.nber.org/papers/w17395 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 September 2011 This is a revised version of a chapter from my UCLA dissertation. Previous versions circulated under the title "Information and the limits to autocracy". I would particularly like to thank Andrew Atkeson and Christian Hellwig for their encouragement and many helpful discussions. I also thank Marios Angeletos, Costas Azariadis, Heski Bar-Isaac, Adam Brandenburger, Ethan Bueno de Mesquita, Ignacio Esponda, Catherine de Fontenay, Matias Iaryczower, Stephen Morris, Alessandro Pavan, Andrea Prat, Hyun Shin, Adam Szeidl, Laura Veldkamp, Iván Werning, seminar participants at the ANU, Boston University, University of Chicago (GSB and Harris), Duke University, FRB Minneapolis, La Trobe University, LSE, University of Melbourne, MIT, NYU, Northwestern University, Oxford University, University of Rochester, UC Irvine, University College London and UCLA and participants at the NBER political economy meetings for their comments. Vivianne Vilar provided excellent research assistance. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2011 by Chris Edmond. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Information Manipulation, Coordination, and Regime Change Chris Edmond NBER Working Paper No. -

Christian Hellwig

CHRISTIAN HELLWIG Professor of Economics, Université Toulouse 1, Capitole Toulouse School of Economics, Manufacture de Tabacs, 21 Allées de Brienne, 31000 Toulouse Email: [email protected] Telephone: +33 (0) 5 61 12 85 93 EDUCATION London School of Economics: Ph.D. in Economics, November 2002 London School of Economics: M.Sc. in Econometrics and Mathematical Economics, with distinction, July 1999 University of Lausanne: B.A. in Economics, July 1998 Oberlin College: Visiting Student, August 1994 – June 1995 CURRENT ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Université de Toulouse 1 Capitole: Professor of Economics, September 2010 – present Toulouse School of Economics: Senior Chair, September 2010 – present Toulouse School of Economics: Scientific Director, September 2019 – present Centre for Economic Policy Research: Research Affiliate, July 2007 – 2011, Research Fellow, 2011 – present European Corporate Governance Institute: Research Affiliate, 2013-- present PREVIOUS ACADEMIC APPPOINTMENTS U.C.L.A., Department of Economics: Assistant Professor, July 2002 – June 2007, Associate Professor (July 2007 - January 2012, on leave after June 2010) Fondazione Ente ‘Luigi Einaudi’, Rome: Visiting Research Fellowship, June 2007, September 2008 Columbia University, Department of Economics: Visiting Assistant Professor, September – December 2006 Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis: Visiting Scholar, September – December 2004 Northwestern University, Department of Economics: Visiting Scholar, March 2004, October 2011 M.I.T., Department of Economics: Visiting Scholar and Instructor, September 2000 – June 2002 L.S.E., Financial Markets Group: Research Assistant, September 1999 – July 2000 PUBLICATIONS IN REFEREED JOURNALS Optimal Regulation in the Presence of Reputation Concerns, with Andy Atkeson and Guillermo Ordonez, Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 130 (1), p. 415-464 (February 2015) Setting the Right Prices for the Wrong Reasons, with Venky Venkateswaran, Journal of Monetary Economics, vol. -

Self-Fulfilling Currency Crises

Self-Fulfilling Currency Crises: TheRoleofInterestRates∗ Christian Hellwig† Arijit Mukherji + Aleh Tsyvinski‡ UCLA University of Minnesota Harvard and NBER May 2006 Abstract We develop a model of currency crises, in which traders are heterogeneously informed, and interest rates are endogenously determined in a noisy rational expectations equilibrium. In our model, multiple equilibria result from distinct roles an interest rate plays in determining domestic asset market allocations and the devaluation outcome. Except for special cases, this finding is not affected by the introduction of noisy private signals. We conclude that the global games results on equilibrium uniqueness do not apply to market-based models of currency crises. 1Introduction It is a commonly held view that financial crises, such as currency crises, bank runs, debt crises or asset price crashes may be the result of self-fulfilling expectations and multiple equilibria. For currency crises, this view is formulated in two broad classes of models. The first, pioneered by Maurice Obstfeld (1986), views a devaluation as the outcome of a run on the central bank’s stock of foreign reserves; in the second class of models, starting from Obstfeld (1996), devaluations are ∗This paper originated from an earlier paper written by the late Arijit Mukherji and Aleh Tsyvinski. We thank the editor, Richard Rogerson, and two anonymous referees for excellent comments and suggestions. We further thank Marios Angeletos, V.V. Chari, Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, Patrick Kehoe, Stephen Morris, Ivan Werning, and especially Andy Atkeson for useful discussions, and seminar audiences at Berkeley, Boston College, Boston University, Cambridge (UK), Harvard, LSE, Kellogg/Northwestern, Rochester, Stanford, UCLA, UC Santa Cruz, and Wharton, as well as the 1st Christmas meetings of German Economists abroad, the 2005 SED meetings in Budapest, and the 2005 World Congress of the Econometric Society for their comments. -

Central Bank Transparency and the Signal Value of Prices1

Central Bank Transparency and the Signal Value of Prices1 Stephen Morris Hyun Song Shin Princeton University London School of Economics Third Version September 2005 1Paper presented at the September 2005 meeting of the Brookings Panel on Economic Activity. We thank Bill Brainard, Ben Friedman, George Perry and Chris Sims for their comments and guidance. We also thank Marios Angeletos, Alan Blinder, Christian Hellwig, Anil Kashyap, Don Kohn, Chris Kent, Phil Lowe, Ellen Meade, Lars Svensson and T. N. Srinivasan for comments are various stages of the project. A central bank must be accountable for its actions, and its decision mak- ing procedures should meet the highest standards of probity and technical competence. In light of the considerable discretion enjoyed by independent central banks, the standards of accountability that such central banks must meet are perhaps even higher than most other public institutions. Central banks must be transparent in this broad sense, and few would question such a proposition. There is a narrower debate on central bank transparency that touches on whether a central bank should publish its forecasts and whether it should have a publicly announced numerical target for in ation. The narrower notion of transparency impinges on issues of accountability and legitimacy also, but its main focus has been on the e ectiveness of monetary policy. Proponents of transparency in this narrower sense point to the impor- tance of the management of expectations in conducting monetary policy. A central bank generally controls directly only the overnight interest rate, \an interest rate that is relevant to virtually no economically interesting trans- actions", as Alan Blinder (1998, p.70) puts it. -

Robust Predictions in Global Games with Multiple Equilibria: Defense Policies Against Currency Attacks

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Angeletos, George-Marios; Hellwig, Christian; Pavan, Alessandro Working Paper Robust predictions in global games with multiple equilibria: Defense policies against currency attacks Discussion Paper, No. 1500 Provided in Cooperation with: Kellogg School of Management - Center for Mathematical Studies in Economics and Management Science, Northwestern University Suggested Citation: Angeletos, George-Marios; Hellwig, Christian; Pavan, Alessandro (2008) : Robust predictions in global games with multiple equilibria: Defense policies against currency attacks, Discussion Paper, No. 1500, Northwestern University, Kellogg School of Management, Center for Mathematical Studies in Economics and Management Science, Evanston, IL This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/59675 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence.