Sudbury's Francophones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Sbodpqipof Xffl Foejoh Xjui Nvtjd Boe Nfssjnfou

)&DEHJ>;HDB?<;"<H?:7O"C7H9>()"(&&- MEM Showtimes for the week of Mar. 23rd, 2007 to Mar. 29th, 2007 Zodiac (14A) FRI & SAT & SUN: 8:00 MON - THU: 8:00 'SBODPQIPOFXFFL Fido (14A) FRI & SAT & SUN: 3:05 9:20 MON - THU: 9:20 Reno 911: Miami (14A) FRI & SAT & SUN: 3:15 9:15 MON - THU: 9:15 Norbit (PG) FRI & SAT & SUN: 1:05 7:05 FOEJOHXJUINVTJD MON - THU: 7:05 Breach (PG) FRI & SAT & SUN: 12:50 7:00 MON - THU: 7:00 Because I Said So (14A) FRI & SAT & SUN: 6:55 9:10 MON - THU: 6:55 9:10 BOENFSSJNFOU Black Snake Moan (14A) FRI & SAT & SUN: 3:20 9:00 MON - THU: 9:00 Music And Lyrics (PG) BY BILL BRADLEY Les Breastfeeders are a FRI & SAT & SUN: 12:55 6:45 MON - THU: 6:45 [email protected] Montreal group guaranteed Stomp The Yard (PG) FRI & SAT & SUN: 9:05 La Nuit sur l’etang is, and to rock the house. Many of MON - THU: 9:05 Happily Never After (G) always has been, a showcase their songs have made it on to FRI & SAT & SUN: 12:45 3:00 Night At The Museum (G) for francophone culture. the charts and its two videos FRI & SAT & SUN: 1:10 3:25 6:50 MON - THU: 6:50 La Nuit sur l’etang has been enjoyed strong rotation on Happy Feet (PG) Musique Plus. Their song FRI & SAT & SUN: 12:45 3:10 exciting audiences with the best of francophone RAINBOW CENTRE Best Movie Deal in Rainbow Country! entertainment for 34 MATINEES, SENIORS, CHILDREN $4.24 years, says president ADULTS EVENINGS $6.50 $4.24 TUESDAYS Gino St. -

FALCONBRIDGE WIND FARM PROJECT Site Considerations Information Renewable Energy Systems Canada Inc

FALCONBRIDGE WIND FARM PROJECT Site Considerations Information Renewable Energy Systems Canada Inc. July 2015 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction to Site Considerations Information 1 2.0 Site Considerations Information Mapping 3 Figure 1: Project Location Figure 2: Natural Features Figure 3: Property Boundaries Figure 4: Municipal and Geographic Township Boundaries 3.0 Site Considerations Information Background Information and Data Sources 8 Site Considerations Information – Falconbridge Wind Farm Project July 2015 1.0 Introduction to Site Considerations Information The Independent Electricity System Operator (IESO) in Ontario has asked proponents of renewable energy projects to submit applications (proposals) for energy contracts. In response to the IESO’s request for proposals (RFP) for phase one of the large renewable procurement (LRP I), Renewable Energy Systems Canada Inc. (RES Canada) is proposing a wind energy project, to be known as the Falconbridge Wind Farm project, which would be located in the City of Greater Sudbury (see Figure 1). The project is expected to be up to 150MW in size, include a transformer substation, low-voltage electrical collector lines, access roads, and a transmission line and construction laydown and work areas. The RFP I LRP requires that specific activities be undertaken prior to submitting a proposal to the IESO. These activities include public, municipal, Aboriginal and other stakeholder consultation and the presentation of Site Considerations mapping and Site Considerations Information (SCI). The SCI -

Greater Sudbury Source Protection Area Assessment Report

Greater Sudbury Source Protection Area Assessment Report Approved on September 2, 2014 Greater Sudbury Source Protection Area Assessment Report The Greater Sudbury Source Protection Area Assessment Report Introduction Limitations of this Report ......................................................................................... 13 Executive Summary ................................................................................................. 14 Sommaire ................................................................................................................ 18 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................. 21 Foreword ................................................................................................................. 22 Preface .................................................................................................................... 24 Part 1 – Report Overview and Methodology Chapter 1 - Overview of the Assessment Report .................................................... 1-5 Chapter 2 - Water Quality Risk Assessment ........................................................... 1-9 Chapter 3 - Water Quantity Risk Assessment ...................................................... 1-23 Part 2 – The Greater Sudbury Source Protection Area Chapter 4 - The Greater Sudbury Source Protection Area: A Tale of Three Rivers 2-5 Chapter 5 - Drinking Water Systems ...................................................................... 2-7 Chapter -

2Nd Qtr June 2017 Council Office 07-20-17

Presented To: City Council For Information Only Presented: Tuesday, Sep 26, 2017 Report Date Monday, Aug 28, 2017 2017 Second Quarter Statement of Council Expenses Type: Correspondence for Information Only Resolution Signed By For Information Only Report Prepared By Christina Dempsey Relationship to the Strategic Plan / Health Impact Co-ordinator of Accounting Assessment Digitally Signed Aug 28, 17 Division Review This report referes to Responsive, Fiscally Prudent, Open Lorraine Laplante Governance: Focus on openness, transparency and Manager of Accounting accountability in everything we do. Digitally Signed Sep 5, 17 Financial Implications Report Summary Apryl Lukezic Co-ordinator of Budgets This report is prepared in accordance with By-law 2016-16F Digitally Signed Sep 8, 17 respecting the payment of expenses for Members of Council and Recommended by the Department Municipal Employees. This report provides information relating to Ed Stankiewicz expenses incurred by Members of Council in the second quarter Executive Director of Finance, Assets of 2017. and Fleet Digitally Signed Sep 5, 17 Recommended by the C.A.O. Financial Implications Ed Archer Chief Administrative Officer There is no financial impact as the amounts are within the Digitally Signed Sep 8, 17 approved operating budget. Background Attached is the second quarter Statement of Council Expenses for the period January 1, 2017 to June 30, 2017. In accordance with the City's by-law on Transparency and Accountability and the Payment of Expenses for Members of Council and Municipal Employees by-law, the City of Greater Sudbury discloses an itemized statement of Council expenses on a quarterly and annual basis. Each Councillor has an Office expense budget of $9,000 to pay for expenses that are eligible under Schedule B of the Payment of Expenses for Members of Council and Municipal Employees by-law. -

White Paper on Francophone Arts and Culture in Ontario Arts and Culture

FRANCOPHONE ARTS AND CULTURE IN ONTARIO White Paper JUNE 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY 05 BACKGROUND 06 STATE OF THE FIELD 09 STRATEGIC ISSUES AND PRIORITY 16 RECOMMANDATIONS CONCLUSION 35 ANNEXE 1: RECOMMANDATIONS 36 AND COURSES OF ACTION ARTS AND CULTURE SUMMARY Ontario’s Francophone arts and culture sector includes a significant number of artists and arts and culture organizations, working throughout the province. These stakeholders are active in a wide range of artistic disciplines, directly contribute to the province’s cultural development, allow Ontarians to take part in fulfilling artistic and cultural experiences, and work on the frontlines to ensure the vitality of Ontario’s Francophone communities. This network has considerably diversified and specialized itself over the years, so much so that it now makes up one of the most elaborate cultural ecosystems in all of French Canada. However, public funding supporting this sector has been stagnant for years, and the province’s cultural strategy barely takes Francophones into account. While certain artists and arts organizations have become ambassadors for Ontario throughout the country and the world, many others continue to work in the shadows under appalling conditions. Cultural development, especially, is currently the responsibility of no specific department or agency of the provincial government. This means that organizations and actors that increase the quality of life and contribute directly to the local economy have difficulty securing recognition or significant support from the province. This White Paper, drawn from ten regional consultations held throughout the province in the fall of 2016, examines the current state of Francophone arts and culture in Ontario, and identifies five key issues. -

Aux Quatre Vents De L'avenir Possible

25.58 mm (1,0071 po) Robert Dickson Aux quatre vents La poésie, c’est la vie intérieure qui déborde en rigoles de rythmes de l’avenir possible en chaloupes qui chavirent Poésies complètes Robert Dickson Robert qui résonne en de notes gonflantes de l’orgue de l’homme universel qui grince grimaçante face à la folie futile c’est le sourire serein de l’enfant endormi c’est des yeux très jeunes grands Poésies complètes comme deux hippopotames crottés devant la renaissance matinale de la lumière Aux quatre vents de l’avenir possible réunit les recueils publiés par ROBERT DICKSON (1944-2007), poète humani ste, traduc t eur zélé, scénariste, comédien, pro fesseur d’uni versité et ani ma teur incontournable du pay sage culturel et litté raire franco-canadien. Dix ans après son décès, la générosité de son être et de sa poésie continue de marquer les cœurs comme les esprits. Aux quatre vents de l’avenir possible – Prix du Gouverneur général pour Humains paysages en temps de paix relative 19,95 $ poésie poésie PdP_cDicksonBCF_170919f.indd 1 17-09-19 15:05 La Bibliothèque canadienne-française a pour objectif de rendre disponibles des œuvres importantes de la littérature canadienne-française à un coût modique. Éditions Prise de parole 205-109, rue Elm Sudbury (Ontario) Canada P3C 1T4 www.prisedeparole.ca Nous remercions le gouvernement du Canada, le Conseil des arts du Canada, le Conseil des arts de l’Ontario et la Ville du Grand Sudbury de leur appui financier. MEP DicksonIntégrale2017-08-18.indd 2 18-02-05 09:50 Aux quatre vents de l’avenir possible MEP DicksonIntégrale2017-08-18.indd 1 18-02-05 09:50 Du même auteur Poésie Libertés provisoires, Sudbury, Éditions Prise de parole, 2005. -

AUTHOR Guindon, Rene; Poulin, Pierre Francophones in Canada: A

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 429 441 FL 025 787 AUTHOR Guindon, Rene; Poulin, Pierre TITLE Francophones in Canada: A Community of Interests. New Canadian Perspectives . Les liens dans la francophonie canadienne. Nouvelles Perspectives Canadiennes. INSTITUTION Canadian Heritage, Ottawa (Ontario). ISBN ISBN-0-662-62279-0 ISSN ISSN-1203-8903 PUB DATE 1996-00-00 NOTE 112p. AVAILABLE FROM Official Languages Support Programs, Department of Canadian Heritage, 15 Eddy, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1A-0M5 (Cat. no. CH-2/1-1996); Tel: 819-994-2224; Web site: http://www.pch.gc.ca/offlangoff/perspectives/index.htm (free). PUB TYPE Books (010)-- Reports Descriptive (141)-- Multilingual/Bilingual Materials (171) LANGUAGE English, French EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Cultural Exchange; Demography; Economic Factors; Educational Mobility; Educational Policy; Faculty Mobility; Foreign Countries; *French; *French Canadians; Information Dissemination; *Intergroup Relations; Kinship; *Land Settlement; *Language Minorities; *Language Role; Mass Media; Migration Patterns; Shared Resources and Services; Social Networks; Social Support Groups; Tourism IDENTIFIERS *Canada; Francophone Education (Canada); Francophonie ABSTRACT This text examines the ties that bind Francophones across Canada to illustrate the diversity and depth of the Canadian Francophone community. Observations are organized into seven chapters. The first looks at the kinship ties of Canadian Francophones, including common ancestral origins, settlement of the Francophone regions, and existence of two particularly large French Canadian families, one in Acadia and one in Quebec. The second chapter outlines patterns of mobility in migration, tourism, and educational exchange. Chapter three looks at the circulation of information within and among Francophone communities through the mass media, both print and telecommunications. The status of cultural exchange (literary, musical, and theatrical) is considered next. -

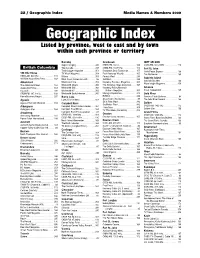

Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by Province, West to East and by Town Within Each Province Or Territory

22 / Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by province, west to east and by town within each province or territory Burnaby Cranbrook fORT nELSON Super Camping . 345 CHDR-FM, 102.9 . 109 CKRX-FM, 102.3 MHz. 113 British Columbia Tow Canada. 349 CHBZ-FM, 104.7mHz. 112 Fort St. John Truck Logger magazine . 351 Cranbrook Daily Townsman. 155 North Peace Express . 168 100 Mile House TV Week Magazine . 354 East Kootenay Weekly . 165 The Northerner . 169 CKBX-AM, 840 kHz . 111 Waters . 358 Forests West. 289 Gabriola Island 100 Mile House Free Press . 169 West Coast Cablevision Ltd.. 86 GolfWest . 293 Gabriola Sounder . 166 WestCoast Line . 359 Kootenay Business Magazine . 305 Abbotsford WaveLength Magazine . 359 The Abbotsford News. 164 Westworld Alberta . 360 The Kootenay News Advertiser. 167 Abbotsford Times . 164 Westworld (BC) . 360 Kootenay Rocky Mountain Gibsons Cascade . 235 Westworld BC . 360 Visitor’s Magazine . 305 Coast Independent . 165 CFSR-FM, 107.1 mHz . 108 Westworld Saskatchewan. 360 Mining & Exploration . 313 Gold River Home Business Report . 297 Burns Lake RVWest . 338 Conuma Cable Systems . 84 Agassiz Lakes District News. 167 Shaw Cable (Cranbrook) . 85 The Gold River Record . 166 Agassiz/Harrison Observer . 164 Ski & Ride West . 342 Golden Campbell River SnoRiders West . 342 Aldergrove Campbell River Courier-Islander . 164 CKGR-AM, 1400 kHz . 112 Transitions . 350 Golden Star . 166 Aldergrove Star. 164 Campbell River Mirror . 164 TV This Week (Cranbrook) . 352 Armstrong Campbell River TV Association . 83 Grand Forks CFWB-AM, 1490 kHz . 109 Creston CKGF-AM, 1340 kHz. 112 Armstrong Advertiser . 164 Creston Valley Advance. -

2 0 1 6 Annual Report

An agency of the Government of Ontario 2015–2016 ANNUAL REPORT Our Vision We will be the leader among science centres in providing inspirational, educational and entertaining science experiences. Our Purpose We inspire people of all ages to be engaged with the science in the world around them. Our Mandate • Offer a program of science learning across Northern Ontario • Operate a science centre • Operate a mining technology and earth sciences centre • Sell consulting services, exhibits and media productions to support the centre’s development Our Professional Values We Are…Accountable, Innovative Leaders We Have…Respect, Integrity and Teamwork Table of Contents 4 Message from the Chair and Chief Executive Officer 6 Fast Facts 8 Spotlight: Economic Impact 10 Spotlight: Serving Northern Ontario 12 Spotlight: Ontario Employer Designation 13 Spotlight: Focus on Leadership 14 Our 5-year Strategic Priorities 17 Strategic Priority 1: Great and Relevant Science Experiences 27 Strategic Priority 2: A Customer-Focused Culture of Operational Excellence 37 Strategic Priority 3: Long Term Financial Stability 46 Science North Funders, Donors and Sponsors 49 Science North Board of Trustees and Committee Members 50 Science North Staff Appendix: Audited Financial Statements Message from the Chair and Chief Executive Officer 2015-16 marked the third year in Science North’s and bring in a wider range of topics allows five-year strategic plan. We’re proud of the Science North to strategically expand organization’s progress in meeting its strategic programming to appeal to a broader audience, priorities and goals and delivering on Science including adults, young families and the teenage North’s mandate. -

Groupe Media Tfo Digital Educational Francophone

GROUPE MEDIA TFO DIGITAL EDUCATIONAL FRANCOPHONE TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY P. 6 SECTION 1 The digital race P. 9 SECTION 2 We can run P. 13 SECTION 3 Transforming education through innovation P. 17 SECTION 4 Contributing to the sustainable development of la francophonie P. 29 SECTION 5 Funding innovation P. 35 SECTION 6 Unleashing more digital innovation P. 39 GROUPE MÉDIA TFO STRATEGIC POSITIONING STATEMENT FOREWORD Transformative digital enterprises contribute to momentum, to leverage the innovation strength defining and developing jobs for young talents that we have developed and more fully realize in the creative sectors. This is the story of the potential of our educational enterprise, Groupe Media TFO, a digital educational and Groupe Média TFO requires a new funding model francophone powerhouse. 1 that is more adequately aligned with its new operational activities. Industry and government in Ontario, across Canada, and globally, are becoming increasingly According to World Economic Forum (WEF) data, focused on innovation and determined to lead Canada ranks 14th on the Network Readiness within the global digital economy. Klaus Schwab Index 2016, a key measurement of the capacity of the WEF and others refer to this as the dawn of countries to leverage emerging technologies of the fourth industrial revolution. Enterprises and digital opportunities.2 We are on the outside recognize that vigorous innovation is a defining of the leading cohort consisting of seven countries: condition of success. Finland, Switzerland, Sweden, Israel, Singapore, the Netherland and the United States. For Canada Within this context, it is equally essential for to catch up, we all have our work cut out for us. -

Marie-Pierre Proulx La Poésie

MARIE-PIERRE PROULX LA POÉSIE DE PATRICE DESBIENS À L’ÉPREUVE DE LA SCÈNE : adaptation textuelle et scénique de L’Homme invisible/The Invisible Man. Mémoire présenté à La Faculté des études supérieures de l’Université d’Ottawa pour l’obtention du grade de maîtrise ès arts (M.A.) Département de théâtre Faculté des Arts Université d’Ottawa Directeur – Professeur Joël Beddows, B.A., D.E.A., Ph.D. Dépôt pour soutenance : le vendredi 30 septembre 2011 Dépôt à la FÉSUO : le vendredi 6 janvier 2012 © Marie-Pierre Proulx, Ottawa, Canada, 2012 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-86365-7 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-86365-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette thèse. -

Hospice News Nouvelles De La Maison

Maison Hospice News Vale Hospice Nouvelles de la Maison Spring/Printemps 2015, Volume 9, No 1 Miigwetch for the gift. Walk of Life / Sentier de la vie “I would prefer a Smudging!” Our Mom, Madeleine Genier, made We have added some wonderful pieces to the Enchanted Forest this announcement shortly after she came to live at the spa (her and the front of the house. Thank you to the families who chose term of endearment for the Maison Vale Hospice). Not being of to honour their loved ones in this way! First Nation background, my brother and I were unsure of what to do with this request. Norm, the Coordinator of Supportive Nous avons ajoutés des beaux morceaux dans la Forêt enchantée Care, was quick to introduce us to Perry McLeod-Shabogesic, et à l’entrée principale, grâce aux familles qui ont choisi Director of Traditional Programming of the Shkagamik-Kwe d’honorer leur être cher sur le Sentier de la vie. Health Centre in Sudbury. On a glorious afternoon, my brother and I, my nephew, Shane, Giselle (Moms’ new friend at the spa), and Norm joined Perry on the dock. Perry expressed the honour he felt in being asked to perform a smudging for our Mom. He patiently explained the ceremony, and we watched as a sense of calm and peace enveloped our Mother. Little did we know that we, too, would be forever changed by this smudging experience and by our stay at Maison Vale Hospice. At the end of the ceremony, a dragonfly flew over us and I said, “Look Mom, that means good luck.” Perry added that, in the First Nation culture, the dragonfly is a symbol of transition, change, the ability to adapt, and self-realization.