Accepted 17 July 2017 GREEN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![<0125701>F7100 [¾Æ¶Ø/¿Μ¾î]Ç¥Áö](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9917/0125701-f7100-%C2%BE%C3%A6%C2%B6%C3%B8-%C2%BF-%C2%BE%C3%AE-%C3%A7%C2%A5%C3%A1%C3%B6-269917.webp)

<0125701>F7100 [¾Æ¶Ø/¿Μ¾î]Ç¥Áö

À_≠à_˝ˇ À_≠à_˝ˇ ÎÙ®˚È: 0017F ENGLISH Revision 1.1 Revision 1.1 PRINTED IN KOREA P/N : MMBB0125701 P/N : MMBB0125701 PRINTED IN KOREA ˆ_Çê_◊ SRPG ˆ_Çê_◊ ®Á¸È ÅÁÏ≥ë•©Ó GPRS Phone ®Á¸È ÅÁÏ≥ë•©Ó ®Á¸È USER’S MANUAL ÎÙ®˚È: 0017F ÎÙ®˚È: MODEL: F7100 ÅÁ≠òÇá Ÿ≠Åá˘˙ ˆ´Å ÅÁ©Á¸È àÃÇ˚¯˙ ŸâÈ ŸâÈ àÃÇ˚¯˙ ÅÁ©Á¸È ˆ´Å Ÿ≠Åá˘˙ ÅÁ≠òÇá Please read this manual carefully ê∑–¸È ò˜ÇÆ ÅÁëË÷ÙÚ Å†ë÷» ௠௠ņë÷» ÅÁëË÷ÙÚ ò˜ÇÆ ê∑–¸È before operating your set. ›Ï≠òÕ ’˝ˇ ÅÁÏ≥ë⁄âÈ. ÅÁÏ≥ë⁄âÈ. ’˝ˇ ›Ï≠òÕ Retain it for future reference. G•P•R•S•P•H•O•N•E G•P•R•S•P•H•O•N•E 1 1 À_≠à_˝ˇ ›Ï≠òÕ ’˝ˇ ÅÁÏ≥ë⁄âÈ. ê∑–¸È ò˜ÇÆ ÅÁ˜Çê◊. ņë÷» ௠ÅÁ≠òÇá Ÿ≠Åá˘˙ ˆ´Å ÅÁ©Á¸È àÃÇ˚¯˙ ŸâÈ ÎÙ®˚È: 0017F ®Á¸È ÅÁÏ≥ë•©Ó ˆ_Çê_◊ SRPG À_≠à_˝ˇ 3 À_≠à_˝ˇ  êËÏ¥ ÅÁ∑Ç†Ò à¸© Îâë˯˙. êë≥âä ’˝ˇ §√≠ ŧëÇ‹. †¸ñ ÅÉÔ¯ ˚°Ù˛ˇ ÀË˝ ÅÉòØÅá ∫–¸≠˘˙ ŸÇà˯˙ ÁÊÔ÷ªÇÍ ÎÏÇ Å†÷» ÅÁ˜Çê◊ ’˝ˇ ÎfiÇÚ ÄÎÒ àø©Å ÀÒ ÎëÇÛÍ Å¬÷ÇÍ Â ê⁄Ì àëôØÖ¯˙ ÅÁ˜Çê◊ ÅÉÛ ÅÁâ√Ǩ˚¯˙.  êÏ≥fl ÅÁ˜Çê◊ ษ‡ ÅÉîÇá Ÿ¸Ç®˘˙ ≤¸Ç¨êfl. ÅÉò˜Ø˘˙ ÅÁfiÏâ¸Ùê≠ Ûœ¸≠ˆÇ. Ÿ© ˚Ùıî≠ ÅÁë©Å§È ÅÁ√÷¸◊ ÀË˝ ÅÉò˜Ø˘˙ ÅÁëË÷Ø˚ÙÚ ÛÅÁ≠Å®˚Ù, ÛÎ≥ÇÀ©Åì ÅÂò˜Ø˘˙ ÅÁ≥Ïø¯˙. -

URBICIDE II 2017 @ IFI IRAQ PALESTINE SYRIA YEMEN Auditorium Postwar Reconstruction AUB

April 6-8 URBICIDE II 2017 @ IFI IRAQ PALESTINE SYRIA YEMEN Auditorium Postwar Reconstruction AUB Thursday, April 6, 2017 9:30-10:00 Registration 10:00-10:30 Welcome and Opening Remarks Abdulrahim Abu-Husayn (Director of the Center for Arts and Humanities, AUB) Nadia El Cheikh (Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, AUB) Halit Eren (Director of IRCICA) 10:30-11:00 Keynote Presentation Heritage Destruction: What can be done in Prevention, Response and Restoration (Francesco Bandarin, UNESCO Assistant Director General for Culture) 11:00-11:15 Coffee Break 11:15-12:45 Urbicide Defined Session Chair: Timothy P. Harrison Background and Overview of Urbicide II (Salma Samar Damluji, AUB) Reconstructing Urbicide (Wendy Pullan, University of Cambridge) Venice Charter on Reconstruction (Wesam Asali, University of Cambridge) 12:45-14:00 Lunch Break 14:00-15:45 Memory, Resilience, and Healing Session Chair: Jad Tabet London – Resilient City (Peter Murray, New London Architecture and London Society) IRCICA’s Experience Rehabilitating Historical Cities: Mostar, al-Quds/Jerusalem, and Aleppo (Amir Pasic, IRCICA, Istanbul) Traumascapes, Memory and Healing: What Urban Designers can do to Heal the Wounds (Samir Mahmood, LAU, Byblos) 15:45-16:00 Coffee Break 16:00-18:00 Lebanon Session Chair: Hermann Genz Post-Conflict Archaeological Heritage Management in Beirut (1993-2017) (Hans Curvers, Independent Scholar) Heritage in Post-Conflict Reconstruction: Assessing the Beirut Experience (Jad Tabet, UNESCO World Heritage Committee) Climate Responsive Design -

The Intentional Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Iraq As a Violation Of

The Intentional Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Iraq as a Violation of Human Rights Submission for the United Nations Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights About us RASHID International e.V. is a worldwide network of archaeologists, cultural heritage experts and professionals dedicated to safeguarding and promoting the cultural heritage of Iraq. We are committed to de eloping the histor! and archaeology of ancient "esopotamian cultures, for we belie e that knowledge of the past is ke! to understanding the present and to building a prosperous future. "uch of Iraq#s heritage is in danger of being lost fore er. "ilitant groups are ra$ing mosques and churches, smashing artifacts, bulldozing archaeological sites and illegall! trafficking antiquities at a rate rarel! seen in histor!. Iraqi cultural heritage is suffering grie ous and in man! cases irre ersible harm. To pre ent this from happening, we collect and share information, research and expert knowledge, work to raise public awareness and both de elop and execute strategies to protect heritage sites and other cultural propert! through international cooperation, advocac! and technical assistance. R&SHID International e.). Postfach ++, Institute for &ncient Near -astern &rcheology Ludwig-Maximilians/Uni ersit! of "unich 0eschwister-Scholl/*lat$ + (/,1234 "unich 0erman! https566www.rashid-international.org [email protected] Copyright This document is distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution .! International license. 8ou are free to copy and redistribute the material in an! medium or format, remix, transform, and build upon the material for an! purpose, e en commerciall!. R&SHI( International e.). cannot re oke these freedoms as long as !ou follow the license terms. -

Orontes Valley وادي اﻟﻌﺎﺻﻲ

© Lonely Planet 154 Orontes Valley وادي اﻟﻌﺎﺻﻲ Bordered by the coastal strip to the west and the scorched desert to the east, the Orontes Valley provides a distinctively different experience from Aleppo to the north and Damascus to the south. While Syrians try to break land-speed records between the aforementioned cities, there are enough attractions in the region to make this more than just a blur outside a bus window. Homs, Syria’s third-largest city, and Hama, its fourth, are attractive stops on the journey north. Homs has a lovely restored souq, a relaxed Christian quarter and friendly locals. Hama is famed for its large norias (water wheels) and riverside parks. It’s most active in summer, when the wheels groan with the flow of the Orontes River, known as Nahr al-Aasi (Rebel River) due to the fact that it flows from south to north – the opposite of most rivers in the region. The striking Roman ruins of Apamea are well worth visiting for the colonnaded grace of the cardo maximus, both longer and wider than Palmyra’s. Careful restoration over the last few decades has turned this once-shapeless site into an evocative one. Far less complex in structure are the intriguing beehive houses found at Sarouj and Twalid Dabaghein, which are still used as dwellings. These conical mud-brick structures are an arresting sight. While the castle of Musyaf is suitably imposing, its connection with one of Islam’s most fascinating sects, the Assassins, is the highlight. Members of this radical, mystical group were known for their ability to infiltrate their enemy and kill its leader, giving rise to the English word ‘assassin’. -

Protecting Cultural Property in Non-International Armed Conflicts: Syria and Iraq

Protecting Cultural Property in Non-International Armed Conflicts: Syria and Iraq Louise Arimatsu and Mohbuba Choudhury 91 INT’L L. STUD. 641 (2015) Volume 91 2015 Published by the Stockton Center for the Study of International Law International Law Studies 2015 Protecting Cultural Property in Non-International Armed Conflicts: Syria and Iraq Louise Arimatsu and Mohbuba Choudhury CONTENTS I. Introduction ................................................................................................ 641 II. Why We Protect Cultural Property .......................................................... 646 III. The Outbreak of the Current Armed Conflicts and the Fate of Cultural Property ....................................................................................................... 655 A. Syria ....................................................................................................... 656 B. Iraq ......................................................................................................... 666 IV. The Legal Landscape in Context ............................................................. 670 A. Obligations on the Parties to the Conflict ....................................... 671 B. Consequences of a Failure to Comply with Obligations ............... 685 V. Concluding Comments .............................................................................. 695 I. INTRODUCTION O n June 24, 2014, a month after ISIS1 leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi de- clared the formation of an Islamic Caliphate stretching from northern -

Prophet and Profit Left Nimrud, Before the Explosions

special report ABOVE The Assyrian palace at Nimrud is blown up by Islamic State militants. Prophet and profit LEFT Nimrud, before the explosions. Experts in the field report from Iraq and Syria on the archaeology lost to Islamic State ideology, and looting to fund terrorism. n her memoir Come Tell Me How You Live, Agatha Christie, of tribute from defeated enemies. Though finds from earlier wife of the British archaeologist Max Mallowan, describes excavations now adorn some of the great museums of the world the happy life of the expedition digging at Chagar Bazaar in – the Iraq Museum, the British Museum, the Louvre – an inspired Ithe Jezirah region of north-eastern Syria. The idyllic scene she programme of excavation and restoration in more recent decades paints was interrupted by WWII, but afterwards they returned had created a unique archaeological park in which one could to the Near East and went on to excavate at Nimrud in a project actually walk round an Assyrian palace with many of its sculptures that was to become one of the defining contributions of British in situ. Tragically this is no more. The building has been largely archaeology in the 20th century. How horrified they would be to destroyed by Islamic State (IS), whose infamous video shows see what has become of that wonderful place. them prising sculptures off the wall, smashing others, and finally Nimrud is unquestionably one of the most important sites blowing up this monument. of the ancient world, a capital city of ancient Assyria through Hatra, 70 miles southwest of Mosul and a jewel in the desert, its time of high empire in 9th-7th centuries BC. -

The Question of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) Student Officer: Jason Markatos Position: Deputy President

Committee/Council: Security Council Issue: The question of the Islamic state of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) Student Officer: Jason Markatos Position: Deputy President Introduction For almost 3 years the world has been facing a grave danger threatening to jeopardize international peace and security. The so called ISIS (Islamic State of Iraq and Syria) or ISIL (Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) or simply Islamic State has terrorized large swaths of Iraq and Syria in its drive to establish through ‘ethnic cleansing’ an Islamic state in the Middle East ruled by the strict law of a caliphate. Its actions have turned the media towards them and nowadays it ranks among the most dangerous terrorist organizations along with Al Qaeda. ISIS is believed to have more than 30,000 fighters, mostly consisting of Sunni Muslims and former jihadists, but this number is expanding as more and more people flee from their countries to fight along with the ISIS. It originates from Al Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) and used to be a branch of that organization until 2013 when a high executive, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi changed its name to ISIS. Since then Al Qaeda distanced itself from ISIS as it grew increasingly violent and intolerant even of Muslims. On March 2015 ISIS had control over territory occupied by 10 million people in Iraq and Syria, as well as limited territorial control in Libya and Nigeria. With the UN reporting 24,000 and thousands of injured only in Iraq a massive genocide is to be expected in the following years unless the international community takes serious action and puts a halt to the actions of ISIS. -

Holding on to the Past, Preparing for the Future: Heritage and Depots in Times of Crisis and Transformation Dr

CODART TWINTIG Warsaw, 21-23 May 2017 – Keynote Lecture 22 May Holding on to the Past, Preparing for the Future: Heritage and Depots in Times of Crisis and Transformation Dr. David Duindam, Lecturer at the University of Amsterdam Full text I would like to thank the organizers for the invitation to speak to you today.i The fact that we are standing in Warsaw is not something we can take for granted. The capital of Poland was almost completely destroyed during World War II. Much of the city was badly damaged during armed conflicts, not unlike other European cities. What was unique in the case of Warsaw was the fact that the Nazis had planned this urbicide before the war as part of their goal to completely efface Polish life and culture. After the Nazis had crushed the Polish resistance in 1944, special forces were put in charge to burn down remaining buildings with a special focus on culturally significant sites. There was no military aim: it was a form of cultural genocide. When the city was liberated, 85% of the historic center was gone. One can ask how to deal with so much emptiness; but one can also ask how to deal with such an excessive amount of history. There was some talk of relocating the city altogether, but in the end it was decided to meticulously reconstruct the historic center with the help of archives and paintings. There is an intimate relationship between the words excess and access. The theme of this congress is the role of storage facilities in light of the cornucopian excess of art objects. -

2015 3 2-10 Approved

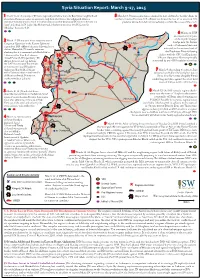

Syria Situation Report: March 9-17, 2015 1 March 11-12: A majority of JN forces reportedly withdrew from the Beit Sahem neighborhood 5 March 17: Syrian regime forces claimed to have downed a “hostile” drone in of southern Damascus under an agreement with local rebel forces. e withdrawal follows a northern Latakia Province. U.S. ocials conrmed the loss of an unarmed U.S. statement issued by a local council in southern Damascus that denounced JN forces in the area as a predator drone, but did not immediately conrm the cause of the crash. “gang” and called on JN leader Abu Mohammed al-Joulani to renounce this JN faction for “oending” the name of JN. 6 March 14: ISIS Qamishli destroyed several parts of the Qarah Qawqaz 2 March 15: JN and rebel forces seized the area of Ayn al-Arab Ras al-Ayn bridge near the former Zarqa near Quraytayn in the Eastern Qalamoun 6 region from ISIS-aliated elements following heavy 9 tomb of Sulayman Shah and clashes. Meanwhile, JN issued a statement retreated to the western bank of clarifying that it is concerned with Hezbollah in the Euphrates River following Aleppo Hasakah Lebanon, rather than the Lebanese 10 clashes with the YPG-led Euphrates Idlib Sara Armed Forces (LAF) specically. JN Volcano Operations Room reportedly did not, however, rule out ghting 5 ar-Raqqa supported by anti-ISIS coalition airstrikes. the LAF if confronted. is follows 3 an interview by local JN leader in Latakia Qalamoun Abu Melik al-Shami 4 7 March 9: According to activists, Iran with a Lebanese news outlet in which Hama delivered ten Sukhoi Su-22 ghter jets to al-Shami conrmed JN intent to Deir ez-Zour Syria. -

Report on the Yazidi Genocide: Mapping Atrocity in Iraq and Syria

REPORT ON THE YAZIDI GENOCIDE: MAPPING ATROCITY IN IRAQ AND SYRIA Abstract: This report outlines ISIS’ transgressions against the Yazidi Community in Iraq and Syria. The report recounts a brief history of the Yazidi people and their culture. The report also provides documentation of existing evidence SAP compiled. The report asserts ISIS’ actions are properly considered genocide. At its conclusion, the report calls on the international community to prioritize holding ISIS fighters responsible for the heinous actions perpetrated against the Yazidi Community in the summer of 2014. Authors: Kelsea Carbajal Cynthia Cline Edmond Gichuru Zachary Lucas Margaret Mabie Shelby Mann Joseph Railey Ashley Repp Syrian Accountability Project 2017-18 Leadership: Project Leader: Professor David M. Crane, Former Chief Prosecutor, Special Court of Sierra Leone Executive Director: Joseph Railey Chief Registrar: Conor Sullivan Chief Investigator: Jasmine Greenfield Senior Editor: Shelby Mann Yazidi Project Team Lead: Margaret Mabie SAP 2017-18 Members: Mohammad Almania, Nate Bosiak, Sam Bubauer, William Bucha, Kelsea Carbajal, Nick Carter, William Cleeton-Grandino, Kristina Cervi, Jordan Charnetsky, John Cronin, Emma Coppola, Brandon DeJesus, Britany Dierken, Michael Flessa, Steven Foss, Cintia Garcia, Kari Gibson, Brandon Golfman, Courtney Griffin, Kseniia Guliaeva, Christian Heneka, Jennifer Hicks, Justin Huber, Paige Ingram, Briannie Kraft, Breanna Leonard, Maggie Mabie, Nicole Macris, Aaron Maher, Natalie Maier, Shelby Mann, Molly McDermid, Alex Mena, Charlotte Munday, Samantha Netzband, Juhyung Oh, Lydia Parenteau, Clara Putnam, Aaron Records, Jade Rodriquez, Jose Estaban Rodriguez, Jenna Romine, Nichole Sands, Ethan Snyder, Zacharia Sonallah, Robert Strum, Lester Taylor, Elliot Vanier, Amit Vyas Special Contributions from: Jodi Upton, Joe Bloss, Amanda Caffey, Ying Chen, Ankur Dang, Kathryn Krawczyk, Baiyu Gao, C.B. -

The Tangible and Intangible Afterlife of Architectural Heritage Destroyed by Acts of War

REBUILDING TO REMEMBER, REBUILDING TO FORGET: THE TANGIBLE AND INTANGIBLE AFTERLIFE OF ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE DESTROYED BY ACTS OF WAR by LAUREN J. KANE A thesis submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Art History, Cultural Heritage and Preservation Studies written under the direction of Dr. Tod Marder and approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May, 2011 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Rebuilding to Remember, Rebuilding to Forget: The Tangible and Intangible Afterlife of Architectural Heritage Destroyed by Acts of War by LAUREN J. KANE Thesis Director: Dr. Tod Marder Aggressors have often attacked sites of valued architectural heritage, believing such destruction will demoralize the targeted nation’s people and irreversibly shake the foundations of the marginalized culture. Of architectural structures that have been specifically targeted and fell victim to enemy attacks over the past decades however, many have been rebuilt in some capacity. This study considers the cases of Old Town Warsaw, the Stari Most in Mostar, and the former World Trade Center site in New York City to understand the ways in which local citizens engaged with the monuments tangible presence and intangible spirit prior to acts of aggression, during the monuments’ physical destruction, and throughout the process of rebuilding. From this analysis, it is concluded that while the rebuilding of valued sites of architectural heritage often reaffirms a culture’s resilience, there is no universal way to deal with the aftermath of the destruction of built heritage. -

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information Local alliances and rivalries shape near-repeat terror activity of al-Qaeda, ISIS and insurgents Yao-Li Chuang, Noam Ben-Asher and Maria R. D’Orsogna Maria R. D’Orsogna. E-mail: [email protected] This PDF file includes: Supplementary text Figs. S1 to S11 Table S1 References for SI reference citations Yao-Li Chuang, Noam Ben-Asher and Maria R. D’Orsogna 1 of 14 www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1904418116 1988 Osama bin Laden founds AQ 1999 Abu Musab al-Zarqawi establishes JTJ 2001 JTJ moves its base to Iraq Oct 17, 2004 JTJ is renamed AQI and joins AQ Jan 15, 2006 AQI and other five groups form MSC Oct 15, 2006 ISI is officially established Apr 8, 2013 ISI is renamed ISIS and expands into Syria Feb 2, 2014 AQ formally disavows ISIS Table S1. Timeline of relations between AQ and ISIS. Supporting Information Text AQ and ISIS affiliates, and L-class groups in the GTD Table S1 summarizes key events in the history of al-Qaeda (AQ) and ISIS, as described in the main text. Our attack data is taken from the Global Terrorist Database (GTD) available from the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) which lists events between Jan 1 1970 and Dec 31 2017. According to the GTD codebook, an event must meet two of the following three criteria to qualify as a terrorist attack: (1) it must have political, religious, or socioeconomic goals; (2) its intent must be to intimidate or coerce an audience larger than the immediate victims; (3) it must fall outside legitimate warfare activities, for example by deliberately targeting civilians.