Article Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Formulary and Prescribing Guidelines

Formulary and Prescribing Guidelines SECTION 1: TREATMENT OF DEPRESSION Section 1. Treatment of depression 1.1 Introduction This guidance should be considered as part of a stepped care approach in the management of depressive disorders. Antidepressants are not routinely recommended for persistent sub-threshold depressive symptoms or mild depression but can be considered in these categories where there is a past history of moderate or severe depression, initial presentation of sub-threshold depressive symptoms for at least 2 years, and persistence of either mild or sub-threshold depression after other interventions1 have failed. The most current NICE guidance should be consulted wherever possible to obtain the most up to date information. For individuals with moderate or severe depression, a combination of antidepressant medication and a high intensity psychological intervention (CBT or IPT) is recommended. When depression is accompanied by symptoms of anxiety, usually treat the depression first. If the person has an anxiety disorder and co-morbid depression or depressive symptoms, consider treating the anxiety first. Also consider offering advice on sleep hygiene, by way of establishing regular sleep and wake times; avoiding excess eating, avoiding smoking and drinking alcohol before sleep; and taking regular physical exercise if possible. Detailed information on the treatment of depression in children and adolescents can be found in section 12. Further guidance on prescribing for older adults and for antenatal/postnatal service users can be found in section 11 and section 20, respectively. 1.2 Approved Drugs for the treatment of Depression in Adults For licensing indications, see Annex 1 Drug5 Formulation5 Comments2,3,4 Caps 20mg, 60mg Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) Fluoxetine Liquid 20mg/5ml 1st line SSRI (based on acquisition cost) Tabs 10mg, 25mg, 50mg Amitriptyline Tricyclic (TCA). -

22 Psychiatric Medications for Monitoring in Primary Care

22 Psychiatric Medications for Monitoring in Primary Care Medication Warnings, Precautions, and Adverse Events Comments Class: SSRI Fluvoxamine Boxed Warnings: Suicidality Used much less than SSRIs in the group of eight Indications: Warnings and Precautions: Similar to other SSRIs medications for prescribing, probably because it has no Adult: OCD Adverse Events: Similar to other SSRIs FDA indication for MDD or any anxiety disorder. Still Child/Adolescent: OCD (10-17 years) somewhat popular as a medication for OCD. Uses: Anxiety, OCD Monitoring: Same as other SSRIs Citalopram Boxed Warning: Suicidality. Escitalopram, one of the SSRIs in the group of Indications: Warnings and Precautions: Similar to other SSRIs medications for prescribing, is an active metabolite of Adult: MDD Adverse Events: Similar to other SSRIs citalopram. Escitalopram reportedly has fewer AEs and Child/Adolescent: None less interaction with hepatic metabolic enzymes than Uses: Anxiety, MDD, OCD citalopram but is otherwise essentially identical. Citalopram offers no advantage other than price, as Monitoring: Same as other SSRIs escitalopram is branded until 2012. Paroxetine Boxed Warnings: Suicidality. Paroxetine used much less than the SSRIs for Indications: Warnings and Precautions: Similar to other SSRIs prescribing, probably because of its nonlinear kinetics. Adult: MDD, OCD, Panic Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Adverse Events: Similar to other SSRIs A study of children and adolescents showed doubling Disorder, Social Anxiety Disorder, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder the dose of paroxetine from 10 mg/day to 20 mg/day Child/Adolescent: None resulted in a 7-fold increase in blood levels (Findling et Uses: Anxiety, MDD, OCD al, 1999). Thus, once metabolic enzymes are saturated, paroxetine levels can increase dramatically with dose Monitoring: Same as other SSRIs increases and decrease dramatically with dose decreases, sometimes leading to adverse events. -

(Ssris) SEROTONIN and NOREPHINEPHRINE REUPTAKE INHIBITORS DOPAMINE and NOREPINEPHRINE RE

VA / DOD DEPRESSION PRACTICE GUIDELINE PROVIDER CARE CARD ANTIDEPRESSANT MEDICATION TABLE CARD 7 Refer to pharmaceutical manufacturer’s literature for full prescribing information SEROTONIN SELECTIVE REUPTAKE INHIBITORS (SSRIs) GENERIC BRAND NAME ADULT STARTING DOSE MAX EXCEPTION SAFETY MARGIN TOLERABILITY EFFICACY SIMPLICITY Citalopram Celexa 20 mg 60 mg Reduce dose Nausea, insomnia, Fluoxetine Prozac 20 mg 80 mg for the elderly & No serious systemic sedation, those with renal toxicity even after headache, fatigue Paroxetine Paxil 20 mg 50 mg or hepatic substantial overdose. dizziness, sexual AM daily dosing. failure Drug interactions may dysfunction Response rate = Can be started at Sertraline Zoloft 50 mg 200 mg include tricyclic anorexia, weight 2 - 4 wks an effective dose First Line Antidepressant Medication antidepressants, loss, sweating, GI immediately. Drugs of this class differ substantially in safety, tolerability and simplicity when used in patients carbamazepine & distress, tremor, warfarin. restlessness, on other medications. Can work in TCA (tricyclic antidepressant) nonresponders. Useful in agitation, anxiety. several anxiety disorders. Taper gradually when discontinuing these medications. SEROTONIN and NOREPHINEPHRINE REUPTAKE INHIBITORS GENERIC BRAND NAME ADULT STARTING DOSE MAX EXCEPTION SAFETY MARGIN TOLERABILITY EFFICACY SIMPLICITY Reduce dose Take with food. Venlafaxine IR Effexor IR 75 mg 375 mg Comparable to BID or TID for the elderly & No serious systemic SSRIs at low dose. dosing with IR. those with renal toxicity. Nausea, dry mouth, Response rate = Daily dosing or hepatic Downtaper slowly to Venlafaxine XR Effexor XR 75 mg 375 mg insomnia, anxiety, 2 - 4 wks with XR. failure prevent clinically somnolence, head- (4 - 7 days at Can be started at significant withdrawal ache, dizziness, ~300 mg/day) an effective dose Dual action drug that predominantly acts like a Serotonin Selective Reuptake inhibitor at low syndrome. -

Drugs That Can Cause Delirium (Anticholinergic / Toxic Metabolites)

Drugs that can Cause Delirium (anticholinergic / toxic metabolites) Deliriants (drugs causing delirium) Prescription drugs . Central acting agents – Sedative hypnotics (e.g., benzodiazepines) – Anticonvulsants (e.g., barbiturates) – Antiparkinsonian agents (e.g., benztropine, trihexyphenidyl) . Analgesics – Narcotics (NB. meperidine*) – Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs* . Antihistamines (first generation, e.g., hydroxyzine) . Gastrointestinal agents – Antispasmodics – H2-blockers* . Antinauseants – Scopolamine – Dimenhydrinate . Antibiotics – Fluoroquinolones* . Psychotropic medications – Tricyclic antidepressants – Lithium* . Cardiac medications – Antiarrhythmics – Digitalis* – Antihypertensives (b-blockers, methyldopa) . Miscellaneous – Skeletal muscle relaxants – Steroids Over the counter medications and complementary/alternative medications . Antihistamines (NB. first generation) – diphenhydramine, chlorpheniramine). Antinauseants – dimenhydrinate, scopolamine . Liquid medications containing alcohol . Mandrake . Henbane . Jimson weed . Atropa belladonna extract * Requires adjustment in renal impairment. From: K Alagiakrishnan, C A Wiens. (2004). An approach to drug induced delirium in the elderly. Postgrad Med J, 80, 388–393. Delirium in the Older Person: A Medical Emergency. Island Health www.viha.ca/mhas/resources/delirium/ Drugs that can cause delirium. Reviewed: 8-2014 Some commonly used medications with moderate to high anticholinergic properties and alternative suggestions Type of medication Alternatives with less deliriogenic -

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors, Fluoxetine and Paroxetine, Attenuate the Expression of the Established Behavioral Sensitization Induced by Methamphetamine

Neuropsychopharmacology (2007) 32, 658–664 & 2007 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0893-133X/07 $30.00 www.neuropsychopharmacology.org Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors, Fluoxetine and Paroxetine, Attenuate the Expression of the Established Behavioral Sensitization Induced by Methamphetamine 1 1 1 1 1 ,1 Yujiro Kaneko , Atsushi Kashiwa , Takashi Ito , Sumikazu Ishii , Asami Umino and Toru Nishikawa* 1 Section of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Tokyo Medical and Dental University Graduate School, Yushima, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, Japan To obtain an insight into the development of a new pharmacotherapy that prevents the treatment-resistant relapse of psychostimulant- induced psychosis and schizophrenia, we have investigated in the mouse the effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI), fluoxetine (FLX) and paroxetine (PRX), on the established sensitization induced by methamphetamine (MAP), a model of the relapse of these psychoses, because the modifications of the brain serotonergic transmission have been reported to antagonize the sensitization phenomenon. In agreement with previous reports, repeated MAP treatment (1.0 mg/kg a day, subcutaneously (s.c.)) for 10 days induced a long-lasting enhancement of the increasing effects of a challenge dose of MAP (0.24 mg/kg, s.c.) on motor activity on day 12 or 29 of withdrawal. The daily injection of FLX (10 mg/kg, s.c.) or PRX (8 mg/kg, s.c.) from 12 to 16 days of withdrawal of repeated MAP administration markedly attenuated the ability of the MAP pretreatment to augment the motor responses to the challenge dose of the stimulant 13 days after the SSRI injection. The repeated treatment with FLX or PRX alone failed to affect the motor stimulation following the challenge of saline and MAP 13 days later. -

Headshop Highs & Lows

HeadshopHeadshop HighsHighs && LowsLows AA PresentationPresentation byby DrDr DesDes CorriganCorrigan HeadshopsHeadshops A.K.A.A.K.A. ““SmartSmart ShopsShops””,, ““HempHemp ShopsShops””,, ““HemporiaHemporia”” oror ““GrowshopsGrowshops”” RetailRetail oror OnlineOnline OutletsOutlets sellingselling PsychoactivePsychoactive Plants,Plants, ‘‘LegalLegal’’ && ““HerbalHerbal”” HighsHighs asas wellwell asas DrugDrug ParaphernaliaParaphernalia includingincluding CannabisCannabis growinggrowing equipment.equipment. Headshops supply Cannabis Paraphernalia HeadshopsHeadshops && SkunkSkunk--typetype (( HighHigh Strength)Strength) CannabisCannabis 1.1. SaleSale ofof SkunkSkunk--typetype seedsseeds 2.2. AdviceAdvice onon SinsemillaSinsemilla TechniqueTechnique 3.3. SaleSale ofof HydroponicsHydroponics && IntenseIntense LightingLighting .. CannabisCannabis PotencyPotency expressedexpressed asas %% THCTHC ContentContent ¾¾ IrelandIreland ¾¾ HerbHerb 6%6% HashHash 4%4% ¾¾ UKUK ¾¾ HerbHerb** 1212--18%18% HashHash 3.4%3.4% ¾¾ NetherlandsNetherlands ¾¾ HerbHerb** 20%20% HashHash 37%37% * Skunk-type SkunkSkunk--TypeType CannabisCannabis && PsychosisPsychosis ¾¾ComparedCompared toto HashHash smokingsmoking controlscontrols ¾¾ SkunkSkunk useuse -- 77 xx riskrisk ¾¾ DailyDaily SkunkSkunk useuse -- 1212 xx riskrisk ¾¾ DiDi FortiForti etet alal .. Br.Br. J.J. PsychiatryPsychiatry 20092009 CannabinoidsCannabinoids ¾¾ PhytoCannabinoidsPhytoCannabinoids-- onlyonly inin CannabisCannabis plantsplants ¾¾ EndocannabinoidsEndocannabinoids –– naturallynaturally occurringoccurring -

Pristiq (Desvenlafaxine Succinate) – First-Time Generic

Pristiq® (desvenlafaxine succinate) – First-time generic • On March 1, 2017, Teva launched AB-rated generic versions of Pfizer’s Pristiq (desvenlafaxine succinate) 25 mg, 50 mg, and 100 mg extended-release tablets for the treatment of major depressive disorder. — Teva launched the 25 mg tablet with 180-day exclusivity. — In addition, Alembic/Breckenridge, Mylan, and West-Ward have launched AB-rated generic versions of Pristiq 50 mg and 100 mg extended-release tablets. — Greenstone’s launch plans for authorized generic versions of Pristiq 25 mg, 50 mg, and 100 mg tablets are pending. — Lupin and Sandoz received FDA approval of AB-rated generic versions of Pristiq 50 mg and 100 mg tablets on June 29, 2015. Lupin’s and Sandoz’s launch plans are pending. • Other serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors approved for the treatment of major depressive disorder include desvenlafaxine fumarate, duloxetine, Fetzima™ (levomilnacipran), Khedezla™ (desvenlafaxine) , venlafaxine, and venlafaxine extended-release. • Pristiq and the other serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors carry a boxed warning for suicidal thoughts and behaviors. • According to IMS Health data, the U.S. sales of Pristiq were approximately $883 million for the 12 months ending on December 31, 2016. optumrx.com OptumRx® specializes in the delivery, clinical management and affordability of prescription medications and consumer health products. We are an Optum® company — a leading provider of integrated health services. Learn more at optum.com. All Optum® trademarks and logos are owned by Optum, Inc. All other brand or product names are trademarks or registered marks of their respective owners. This document contains information that is considered proprietary to OptumRx and should not be reproduced without the express written consent of OptumRx. -

The Psychoactive Effects of Psychiatric Medication: the Elephant in the Room

Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 45 (5), 409–415, 2013 Published with license by Taylor & Francis ISSN: 0279-1072 print / 2159-9777 online DOI: 10.1080/02791072.2013.845328 The Psychoactive Effects of Psychiatric Medication: The Elephant in the Room Joanna Moncrieff, M.B.B.S.a; David Cohenb & Sally Porterc Abstract —The psychoactive effects of psychiatric medications have been obscured by the presump- tion that these medications have disease-specific actions. Exploiting the parallels with the psychoactive effects and uses of recreational substances helps to highlight the psychoactive properties of psychi- atric medications and their impact on people with psychiatric problems. We discuss how psychoactive effects produced by different drugs prescribed in psychiatric practice might modify various disturb- ing and distressing symptoms, and we also consider the costs of these psychoactive effects on the mental well-being of the user. We examine the issue of dependence, and the need for support for peo- ple wishing to withdraw from psychiatric medication. We consider how the reality of psychoactive effects undermines the idea that psychiatric drugs work by targeting underlying disease processes, since psychoactive effects can themselves directly modify mental and behavioral symptoms and thus affect the results of placebo-controlled trials. These effects and their impact also raise questions about the validity and importance of modern diagnosis systems. Extensive research is needed to clarify the range of acute and longer-term mental, behavioral, and physical effects induced by psychiatric drugs, both during and after consumption and withdrawal, to enable users and prescribers to exploit their psychoactive effects judiciously in a safe and more informed manner. -

Duloxetine for Chronic Pain Relief

Patient Information Leaflet Duloxetine for Chronic Pain Relief Produced By: Chronic Pain Service April 2014 Review due April 2017 1 If you require this leaflet in another language, large print or another format, please contact the Quality Team, telephone 01983 534850, who will advise you. Duloxetine ( Cymbalta ) is a medicine used to relieve chronic pain and treat low mood. It is often helpful for nerve-related pain or pain sensitivity (also called central sensitisation ). It has a different way of relieving pain than standard pain killers and is often prescribed in combination. If used for pain other than diabetes-related neuropathic pain it is formally used outside it’s product license as per individual decision by your pain specialist/doctor. As it affects the central nervous system in complex ways, the effect often takes a while to be felt and requires regular intake . We recommend a trial of at least four weeks to judge the effect. If good, it should be taken on a regular long-term basis; if there is no distinct relief it should be discontinued after the trial period. If you suffer with seizures/epilepsy, glaucoma and poorly controlled high blood pressure, Duloxetine should be used with caution and at a lower dose (up to 60mg per day). The most common side effect is drowsiness/dizziness therefore it is best time to take it in the evening. There are many other possible side effects, but most are uncommon, rare or very rare (please take a look at the product leaflet) We suggest that you avoid driving for at least 2 days after starting or increasing the dose of this medication. -

Desvenlafaxine

https://providers.amerigroup.com CONTAINS CONFIDENTIAL PATIENT INFORMATION desvenlafaxine Prior Authorization of Benefits (PAB) Form Complete form in its entirety and fax to: Prior Authorization of Benefits Center at 1-844-512-9004 Provider Help Desk 1-800-454-3730 1. PATIENT INFORMATION 2. PHYSICIAN INFORMATION Patient Name: Prescribing Physician: Patient ID #: Physician Address: Patient DOB: Physician Phone #: Date of Rx: Physician Fax #: Patient Phone #: Physician Specialty: Patient Email Address: Physician DEA: Physician NPI #: Physician Email Address: 3. MEDICATION 4. STRENGTH 5. DIRECTIONS 6. QUANTITY PER 30 DAYS desvenlafaxine Specify: 7. DIAGNOSIS: 8. APPROVAL CRITERIA: CHECK ALL BOXES THAT APPLY NOTE: Any areas not filled out are considered not applicable to your patient & MAY AFFECT THE OUTCOME of this request. □ Yes □ No Documentation of a previous trial and therapy failure at a therapeutic dose with two preferred generic SSRIs* has been provided If No: □ Yes □ No Documented evidence is provided that the use of these agents would be medically contraindicated □ Yes □ No Documentation of a previous trial and therapy failure at a therapeutic dose with one preferred generic SNRI** has been provided If No: □ Yes □ No Documented evidence is provided that the use of these agents would be medically contraindicated □ Yes □ No Documentation of a previous trial and therapy failure at a therapeutic dose with one non-SSRI/SNRI generic antidepressant** has been provided If No: □ Yes □ No Documented evidence is provided that the use of these -

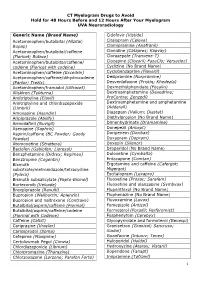

CT Myelogram Drugs to Avoid Hold for 48 Hours Before and 12 Hours After Your Myelogram UVA Neuroradiology

CT Myelogram Drugs to Avoid Hold for 48 Hours Before and 12 Hours After Your Myelogram UVA Neuroradiology Generic Name (Brand Name) Cidofovir (Vistide) Acetaminophen/butalbital (Allzital; Citalopram (Celexa) Bupap) Clomipramine (Anafranil) Acetaminophen/butalbital/caffeine Clonidine (Catapres; Kapvay) (Fioricet; Butace) Clorazepate (Tranxene-T) Acetaminophen/butalbital/caffeine/ Clozapine (Clozaril; FazaClo; Versacloz) codeine (Fioricet with codeine) Cyclizine (No Brand Name) Acetaminophen/caffeine (Excedrin) Cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril) Acetaminophen/caffeine/dihydrocodeine Desipramine (Norpramine) (Panlor; Trezix) Desvenlafaxine (Pristiq; Khedezla) Acetaminophen/tramadol (Ultracet) Dexmethylphenidate (Focalin) Aliskiren (Tekturna) Dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine; Amitriptyline (Elavil) ProCentra; Zenzedi) Amitriptyline and chlordiazepoxide Dextroamphetamine and amphetamine (Limbril) (Adderall) Amoxapine (Asendin) Diazepam (Valium; Diastat) Aripiprazole (Abilify) Diethylpropion (No Brand Name) Armodafinil (Nuvigil) Dimenhydrinate (Dramamine) Asenapine (Saphris) Donepezil (Aricept) Aspirin/caffeine (BC Powder; Goody Doripenem (Doribax) Powder) Doxapram (Dopram) Atomoxetine (Strattera) Doxepin (Silenor) Baclofen (Gablofen; Lioresal) Droperidol (No Brand Name) Benzphetamine (Didrex; Regimex) Duloxetine (Cymbalta) Benztropine (Cogentin) Entacapone (Comtan) Bismuth Ergotamine and caffeine (Cafergot; subcitrate/metronidazole/tetracycline Migergot) (Pylera) Escitalopram (Lexapro) Bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol) Fluoxetine (Prozac; Sarafem) -

Milnacipran for Pain in Fibromyalgia in Adults

Milnacipran for pain in fibromyalgia in adults (Review) Cording M, Derry S, Phillips T, Moore RA, Wiffen PJ This is a reprint of a Cochrane review, prepared and maintained by The Cochrane Collaboration and published in The Cochrane Library 2015, Issue 10 http://www.thecochranelibrary.com Milnacipran for pain in fibromyalgia in adults (Review) Copyright © 2015 The Cochrane Collaboration. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. TABLE OF CONTENTS HEADER....................................... 1 ABSTRACT ...................................... 1 PLAINLANGUAGESUMMARY . 2 SUMMARY OF FINDINGS FOR THE MAIN COMPARISON . ..... 4 BACKGROUND .................................... 6 OBJECTIVES ..................................... 7 METHODS ...................................... 7 RESULTS....................................... 9 Figure1. ..................................... 10 Figure2. ..................................... 12 Figure3. ..................................... 13 Figure4. ..................................... 14 Figure5. ..................................... 18 DISCUSSION ..................................... 21 AUTHORS’CONCLUSIONS . 22 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . 23 REFERENCES ..................................... 23 CHARACTERISTICSOFSTUDIES . 27 DATAANDANALYSES. 38 Analysis 1.1. Comparison 1 Milnacipran 100 mg/day versus placebo, Outcome 1 At least 30% pain relief. 39 Analysis 1.2. Comparison 1 Milnacipran 100 mg/day versus placebo, Outcome 2 PGIC ’much improved’ or ’very much improved’.................................... 40 Analysis 1.3. Comparison