One-Off Report: Spain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commission of the European Communities

COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES c0ll(85) 692 f inaL ,51 tu Brussets, 6 December 19E5 e ProposaI for a COUNCIL REGULATION (EEC) concerni ng the definition of the concept of "originating products" and methods of administrative cooperation in the trade betveen the customs terri tory of the Community, Ceuta and l{eLi[La and the Canary Islands (submitted to the Councit by the Cqnmission) l, COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES cOir(85) 692 finat BrusseLs, 6 December 1985 ProposaL for a COUNCIL REGULATION (EEC) concerning the definition of the concept of "originating products" and methods of administrative cooperation in the trade betreen the customs territory of the Community, Ceuta and ttletiLLa and the Canary Islands (submitted to the CouncjL by the Ccrnmission) COlq(85) 692 finaL EIP'JA}IATORY NOTE According to Protocol no 2 of the Act of adhesion, the Spanish territories of the Canary Islandsr Ceuta and !{elilla are not lncluded in the customs territory of the Comnunityr and their trade nith the latter will beneflt from a reciprocal preferential systen, which wirl end, with duty free entry, with aome exceptions, after the transitional period. Article 9 of the said Protocol provides for the Council to adopt, voting be- fore the lst of Mardr 1986, by qualified majority on a ComissLon proposal, the origin rules to be applied in the trade between these territories and the Comunity. At the adhesion negotiations, the inter-ministeriar conference agrreed on a draft project of origin rules corresponding to those already adopted i-n the Communlty preferential schemes lrith Third Countries. -

The Iberian-Guanche Rock Inscriptions at La Palma Is.: All Seven Canary Islands (Spain) Harbour These Scripts

318 International Journal of Modern Anthropology Int. J. Mod. Anthrop. 2020. Vol. 2, Issue 14, pp: 318 - 336 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ijma.v2i14.5 Available online at: www.ata.org.tn & https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ijma Research Report The Iberian-Guanche rock inscriptions at La Palma Is.: all seven Canary Islands (Spain) harbour these scripts Antonio Arnaiz-Villena1*, Fabio Suárez-Trujillo1, Valentín Ruiz-del-Valle1, Adrián López-Nares1, Felipe Jorge Pais-Pais2 1Department of Inmunology, University Complutense, School of Medicine, Madrid, Spain 2Director of Museo Arqueológico Benahoarita. C/ Adelfas, 3. Los Llanos de Aridane, La Palma, Islas Canarias. *Corresponding author: Antonio Arnaiz-Villena. Departamento de Inmunología, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Complutense, Pabellón 5, planta 4. Avd. Complutense s/n, 28040, Spain. E-mail: [email protected] ; [email protected]; Web page:http://chopo.pntic.mec.es/biolmol/ (Received 15 October 2020; Accepted 5 November 2020; Published 20 November 2020) Abstract - Rock Iberian-Guanche inscriptions have been found in all Canary Islands including La Palma: they consist of incise (with few exceptions) lineal scripts which have been done by using the Iberian semi-syllabary that was used in Iberia and France during the 1st millennium BC until few centuries AD .This confirms First Canarian Inhabitants navigation among Islands. In this paper we analyze three of these rock inscriptions found in westernmost La Palma Island: hypotheses of transcription and translation show that they are short funerary and religious text, like of those found widespread through easternmost Lanzarote, Fuerteventura and also Tenerife Islands. They frequently name “Aka” (dead), “Ama” (mother godness) and “Bake” (peace), and methodology is mostly based in phonology and semantics similarities between Basque language and prehistoric Iberian-Tartessian semi-syllabary transcriptions. -

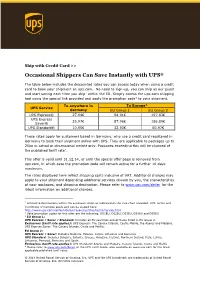

Occasional Shippers Can Save Instantly with UPS®

Ship with Credit Card >> Occasional Shippers Can Save Instantly with UPS® The table below includes the discounted rates you can access today when using a credit card to book your shipment on ups.com. No need to sign-up, you can ship as our guest and start saving each time you ship1 within the EU. Simply access the ups.com shipping tool using the special link provided and apply the promotion code2 to your shipment. To anywhere in To Europe3 UPS Service Germany EU Group 1 EU Group 2 UPS Express® 27.94€ 94.01€ 197.83€ UPS Express 25.97€ 87.96€ 186.89€ Saver® UPS Standard® 10.95€ 32.93€ 50.97€ These rates apply for customers based in Germany, who use a credit card registered in Germany to book their shipment online with UPS. They are applicable to packages up to 20kg in actual or dimensional weight only. Packages exceeding this will be charged at the published tariff rate4. This offer is valid until 31.12.14, or until the special offer page is removed from ups.com, in which case the promotion code will remain active for a further 10 days maximum. The rates displayed here reflect shipping costs inclusive of VAT. Additional charges may apply to your shipment depending additional services chosen by you, the characteristics of your packages, and shipping destination. Please refer to www.ups.com/de/en for the latest information on additional charges. 1 Limited to destinations within the European Union as indicated on the rate chart provided. UPS Terms and Conditions of Carriage apply and can be viewed here: http://www.ups.com/content/de/en/resources/ship/terms/service.html 2 Valid promotion codes for this offer are the following: DE1EU, DE2EU, DE3EU, DE4EU and DE5EU 3 EU Group 1: UPS Express / Saver / Standard: Includes all EU countries except those listed in EU Group 2. -

In the Canary Islands: a Prospective Analysis of the Concept of Tricontinentality

The “African being” in the Canary Islands: a prospective analysis of the concept of Tricontinentality José Otero Universidad de La Laguna 2017 1. Introduction Are the Canary Islands considered part of Africa? Instead of answering directly this question, my intervention today - which is a summary of my PhD dissertation- will go over the different responses to that question by local intellectual elites since the conquer and colonization of the Canary Islands. There are certain connections between Africa and the archipelago and I would like to present them from three different perspectives: 1) Understanding the indigenous inhabitant of the Canary Islands as an “African being”. 2) Reconstructing the significance of the Canary Islands in the Atlantic slave trade and its effects on some local artists in the first decades of the twentieth century. 3) Restructuring the interpretation of some Africanity in the cultural and political fields shortly before the end of Franco’s dictatorial regime. 2. The guanches and Africa: the repetition of denial The Canary Islands were inhabited by indigenous who came from North Africa in different immigrant waves –at the earliest– around the IX century B.C. (Farrujía, 2017). The conquest of the Islands by the Crown of Castile was a complex phenomenon and took place during the entire XV century. Knowledge of indigenous cultures has undoubtedly been the main theme of any historical and anthropological reflection made from the archipelago and even today, the circumstances around the guanches provokes discussions and lack of consensus across the social spectrum, not just among academic disciplines but in popular culture too. -

Molina-Et-Al.-Canary-Island-FH-FEM

Forest Ecology and Management 382 (2016) 184–192 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Forest Ecology and Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foreco Fire history and management of Pinuscanariensis forests on the western Canary Islands Archipelago, Spain ⇑ Domingo M. Molina-Terrén a, , Danny L. Fry b, Federico F. Grillo c, Adrián Cardil a, Scott L. Stephens b a Department of Crops and Forest Sciences, University of Lleida, Av. Rovira Roure 191, 25198 Lleida, Spain b Division of Ecosystem Science, Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management, 130 Mulford Hall, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-3114, USA c Department of the Environment, Cabildo de Gran Canaria, Av. Rovira Roure 191, 25198 Gran Canaria, Spain article info abstract Article history: Many studies report the history of fire in pine dominated forests but almost none have occurred on Received 24 May 2016 islands. The endemic Canary Islands pine (Pinuscanariensis C.Sm.), the main forest species of the island Received in revised form 27 September chain, possesses several fire resistant traits, but its historical fire patterns have not been studied. To 2016 understand the historical fire regimes we examined partial cross sections collected from fire-scarred Accepted 2 October 2016 Pinuscanariensis stands on three western islands. Using dendrochronological methods, the fire return interval (ca. 1850–2007) and fire seasonality were summarized. Fire-climate relationships, comparing years with high fire occurrence with tree-ring reconstructed indices of regional climate were also Keywords: explored. Fire was once very frequent early in the tree-ring record, ranging from 2.5 to 4 years between Fire management Fire suppression fires, and because of the low incidence of lightning, this pattern was associated with human land use. -

Canary Islands

CANARY ISLANDS EXP CAT PORT CODE TOUR DESCRIPTIVE Duration Discover Agadir from the Kasbah, an ancient fortress that defended this fantastic city, devastated on two occasions by two earthquakes Today, modern architecture dominates this port city. The vibrant centre is filled with Learn Culture AGADIR AGADIR01 FASCINATING AGADIR restaurants, shops and cafes that will entice you to spend a beautiful day in 4h this eclectic city. Check out sights including the central post office, the new council and the court of justice. During the tour make sure to check out the 'Fantasy' show, a highlight of the Berber lifestyle. This tour takes us to the city of Taroudant, a town noted for the pink-red hue of its earthen walls and embankments. We'll head over by coach from Agadir, seeing the lush citrus groves Sous Valley and discovering the different souks Discover Culture AGADIR AGADIR02 SENSATIONS OF TAROUDANT scattered about the city. Once you have reached the centre of Taroudant, do 5h not miss the Place Alaouine ex Assarag, a perfect place to learn more about the culture of the city and enjoy a splendid afternoon picking up lifelong mementos in their stores. Discover the city of Marrakech through its most emblematic corners, such as the Mosque of Kutubia, where we will make a short stop for photos. Our next stop is the Bahia Palace, in the Andalusian style, which was the residence of the chief vizier of the sultan Moulay El Hassan Ba Ahmed. There we will observe some of his masterpieces representing the Moroccan art. With our Feel Culture AGADIR AGADIR03 WONDERS OF MARRAKECH guides we will have an occasion to know the argan oil - an internationally 11h known and indigenous product of Morocco. -

In Gran Canaria

Go Slow… in Gran Canaria Naturetrek Tour Report 7th – 14th March 2020 Gran Canaria Blue Chaffinch Canary Islands Red Admiral Report & images by Guillermo Bernal Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Go Slow… in Gran Canaria Tour participants: Guillermo Bernal and Maria Belén Hernández (leaders) together with nine Naturetrek clients Summary Gran Canaria may be well-known as a popular sun-seekers’ destination, but it contains so much more, with a wealth of magnificent scenery, fascinating geology and many endemic species or subspecies of flowers, birds and insects. On this, the second ‘Go Slow’ tour, we were able to enjoy some of the best of the island’s rugged volcanic scenery, appreciating the contrasts between the different habitats such as the bird- and flower-rich Laurel forest and the dramatic ravines, and the bare rain-starved slopes of the south. The sunset from the edge of the Big Caldera in the central mountains, the wonderful boat trip, with our close encounters with Atlantic Spotted Dolphins and Cory’s Shearwater, the Gran Canarian Blue Chaffinch and the vagrant Abyssinian Roller, the echoes of past cultures in the caves of Guayadeque, and the beauty of the Botanic Garden with its Giant Lizards were just some of the many highlights. There was also time to relax and enjoy the pools in our delightful hotel overlooking the sea. Good weather with plenty of sunshine, comfortable accommodation, delicious food and great company all made for an excellent week. -

Risco Caído and the Sacred Mountains of Gran Canaria Cultural Landscape

Additional information requested by ICOMOS regarding the nomination of the Risco Caído and the Sacred Mountains of Gran Canaria Cultural Landscape for Inscription on the World Heritage List 2018 November 2018 1 Index This report includes the additional information requested by ICOMOS in its letter of the 8th October 2018 concerning the nomination process of Risco Caido and Sacred Mountains of Gran Canaria Cultural Landscape. It includes the information requested, along with the pertinent comments on each point. 1. Description of de property p. 3 2. Factors affecting the property p. 54 3. Boundaries and the buffer zone p. 59 4. Protection p. 68 5. Conservation p. 79 6. Management p. 87 7. Involvement of the local communities p. 93 2 1 Description of the property ICOMOS would be pleased if the State Party could provide a more accurate overview of the current state of archaeological research in the Canary Islands in order to better understand Gran Canaria's place in the history of the archipelago. The inventory project begun at the initiative of Werner Pichler which mentions the engravings of the north of Fuerteventura with 2866 individual figures and the work briefly mentioned in the nomination dossier of several researchers from the Universidad de La Laguna, on the island of Tenerife, and the Universidad de Las Palmas, on the island of Gran Canaria could assist in this task. Table 2.a.llists all the attributes and components of the cultural landscape of Risco Caldo and its buffer zone (p. 34). However, only part of the sites are described in the nomination dossier (p. -

Paradise Gardens of Morocco, the Canary Islands, Madeira & Portugal Cruise

PARADISE GARDENS OF MOROCCO, THE CANARY ISLANDS, MADEIRA & PORTUGAL CRUISE Paradise Gardens of Morocco, the Canary Islands, Madeira & Portugal 17 day Cruise aboard Caledonian Sky. ITINERARY Day 1 Arrive Marrakesh Be met at the airport and transfer to your hotel. Later this evening, enjoy Welcome Drinks followed by dinner. Stay: Three Nights, Marrakesh, 5-star hotel Day 2 Majorelle Gardens, La Mamounia Take a guided tour of Marrakesh including the Koutoubia minaret, the Bahia palace, the Royal Pavilion and Majorelle Gardens. Enjoy lunch at La Mamounia, where Winston Churchill liked to stay, and visit the beautiful gardens where he often set up his easel. Visit the artisan quarter, the colourful souks and Dar Si Said Museum before taking a stroll around Jamaa El Fna, the bustling, main city square. Day 3 Paradise Gardens Today, visit the 800-year-old royal pleasure gardens known as the Agdal. We also take in a couple of gardens featured on 01432 507 280 (within UK) [email protected] | small-cruise-ships.com Monty Don’s series Paradise Gardens. endemic plants. Day 4 Marrakesh to Casablanca Day 8 El Hierro, Freedom of Choice Visit the Bert Flint Museum which houses Moroccan art and Today we arrive at El Hierro, the smallest of the Canary Islands, artefacts. Travel to Casablanca this afternoon, well known from with a natural bounty way beyond its size. Plant hunter Tom Hart the 1942 film of the same name. Stay: Casablanca, 5-star hotel Dyke referred to this small island as 'the botanical Galápagos of Europe' because of the many rare endemic plant species that Day 5 Hassan II Mosque, fly to Tenerife grow here and nowhere else. -

SPAIN SEA and LAND ARRIVALS JAN-DEC 2019 SPAIN SEA and LAND ARRIVALS 1 Jan- 31 Dec 2019 Location of Refugee & Migrant Arrivals1 Eastern Med

SPAIN SEA AND LAND ARRIVALS JAN-DEC 2019 SPAIN SEA AND LAND ARRIVALS 1 Jan- 31 Dec 2019 Location of refugee & migrant arrivals1 Eastern Med. & Balearic Islands 2,250 Andalusia: Motril & Almeria Andalusia: Malaga 10,435 3,665 Andalusia: Cadiz - Strait of Gibraltar 5,600 Ceuta 1,965 Canary Islands Melilla Ceuta Melilla 2,700 5,890 (Spain) (Spain) 1,965 5,890 1,360 4,985 605 905 Land Sea arrivals arrivals 32,513 Jan-Dec 2019 65,383 Jan-Dec 2018 Dead and Missing² Land Land 6,345 6,814 Jan-Dec 2019 20% 10% 20% 681 50% Sea Dif.2018 26,168 58,569 Jan-Dec 2018 80% 90% 854 Arrivals trend by month 10,000 Sea arrivals 2018 2019 8,000 Land arrivals 6,000 4,000 2,149 2,000 616 0 Jan-18 Feb-18 Ma r- 18 Apr-18 Ma y-18 Jun-18 Jul-18 Au g- 18 Sep-18 Oct-18 N ov- 18 Dec-18 Jan-19 Feb-19 Ma r- 19 Apr-19 Ma y-19 Jun-19 Jul-19 Au g- 19 Sep-19 Oct-19 N ov- 19 Dec-19 Most common nationalities of arrivals, Jan-Dec 2019 Demography of arrivals, Jan-Dec 2019 8,271 (25%) Morocco 13,076 (20%) 5,124 (16%) Children Guinea 13,053 (20%) 12% 5,025 (15%) Algeria 5,801 (9%) Women 3,298 (10%) 12% Mali 10,340 (16%) Men 2,867 (9%) Côte d'Ivoire 76% 5,273 (8%) 2,378 (7%) Senegal 2,133 (3%) 1,238 (4%) Tunisia 557 (1%) 1,031 (3%) Syrian Arab Rep. -

Peer Review Report

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Directorate for Education Education Management and Infrastructure Division Programme on Institutional Management in Higher Education (IMHE) Supporting the contribution of Higher Education Institutions to Regional Development Peer Review Report Canary Islands, Spain Chris Duke, Francisco Marmolejo, Jose Ginés Mora, Walter Uegama July 2006 The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the OECD or its member countries. 1 This Peer Review Report is based on the review visit to the Canaries in April 2006, the regional Self- Evaluation Report, and other background material. As a result, the report reflects the situation up to that period. The preparation and completion of this report would not have been possible without the support of very many people and organisations. OECD/IMHE and the Peer Review Team for the Canaries wish to acknowledge the substantial contribution of the region, particularly through its Coordinator, the authors of the Self-Evaluation Report, and its Regional Steering Group. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE......................................................................................................................................5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...........................................................................................................7 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS....................................................................................12 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................13 -

Isabel Kentengian – CV – September 2020

Isabel Maria Kentengian The College of New Jersey Department of World Languages and Cultures Bliss Hall 324 2000 Pennington Road Ewing, NJ 08648 +1(609) 771-2699 [email protected] I. Academic and Professional Employment The College of New Jersey, Ewing, New Jersey Instructor, World Languages and Cultures, Fall 2004-present Director, TCNJ Semester in Spain 2019, TCNJ in Spain 2016 Co-Director, TCNJ in Madrid, 2005, 2008 University Children’s Eye Center, East Brunswick, New Jersey Practice Administrator, 1993-2004 Middlesex College, Edison, New Jersey Instructor, English as a Second Language, 1996-1998 University of Illinois, Chicago, Illinois Instructor, Tutorium in Intensive English, 1991-1992 Columbia University, New York, New York Instructor, American Language Program, New York, NY, 1988-1991 MacCormac College, Chicago, Illinois Director and Chair, English Language Institute, 1987-1988 Director, Evening Program of the English Language Institute, 1985-1987 Instructor, English Language Institute, 1982-1985 Oak Park Elementary Schools, Oak Park, Illinois Teacher and Curriculum Coordinator, Spanish Language Program, 1982-1984 Iberlengua, Madrid, Spain English Instructor, 1978-1979 Colegio Base, Madrid, Spain. Middle and High School English Teacher, 1978 II. Educational Background New York University, Steinhardt School of Culture, Education and Human Development Ph.D., International Education. Focus: Global Education. 2020. Dissertation Title: "It's Just Another Variety": Experiences of Imagined Identities of Latino Spanish Heritage Speakers in Spain Dissertation Advisors: Philip Hosay, Ph.D. (Chair); Sonia Das, Ph.D.; Miriam Eisenstein Ebsworth, Ph.D. University of Illinois, Chicago, Illinois.1985. M.A., Applied Linguistics - Focus on Hispanic Linguistics and Second Language Acquisition. Thesis Title: “Effects of Age and Gender on Generic Pronoun Choice: A Multivariate Experimental Approach” Thesis Advisor: Elliot Judd, Ph.D.