Memorial to Thomas A. Steven (1917–2013) PETER D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of Beaver County, Utah Centennial County History Series

A HISTORY OF 'Beaver County Martha Sonntag Bradley UTAH CENTENNIAL COUNTY HISTORY SERIES A HISTORY OF 'Beaver County Martha Sonntag Bradley The settlement of Beaver County began in February 1856 when fifteen families from Parowan moved by wagon thirty miles north to Beaver Valley. The county was created by the Utah legislature on 31 January 1856, a week before the Parowan group set out to make their new home. However, centuries before, prehistoric peoples lived in the area, obtaining obsidian for arrow and spear points from the Mineral Mountains. Later, the area became home to Paiute Indians. Franciscan Friars Dominguez and Escalante passed through the area in October 1776. The Mormon settlement of Beaver devel oped at the foot of the Tushar Mountains. In 1859 the community of Minersville was es tablished, and residents farmed, raised live stock, and mined the lead deposits there. In the last quarter of the nineteenth century the Mineral Mountains and other locations in the county saw extensive mining develop ment, particularly in the towns of Frisco and Newhouse. Mining activities were given a boost with the completion of the Utah South ern Railroad to Milford in 1880. The birth place of both famous western outlaw Butch Cassidy and inventor of television Philo T. Farnsworth, Beaver County is rich in history, historic buildings, and mineral treasures. ISBN: 0-913738-17-4 A HISTORY OF 'Beaver County A HISTORY OF Beaver County Martha Sonntag Bradley 1999 Utah State Historical Society Beaver County Commission Copyright © 1999 by Beaver County Commission All rights reserved ISBN 0-913738-17-4 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 98-61325 Map by Automated Geographic Reference Center—State of Utah Printed in the United States of America Utah State Historical Society 300 Rio Grande Salt Lake City, Utah 84101-1182 Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vii GENERAL INTRODUCTION ix CHAPTER 1 Beaver County: The Places That Shape Us . -

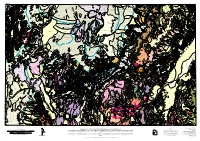

Interim Geologic Map of the Southwestern Quarter of the Beaver 30' X 60' Quadrangle Utah Department of Natural Resources

Plate 1 UTAH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Utah Geological Survey Open-File Report 686DM a division of Interim Geologic Map of the Southwestern Quarter of the Beaver 30' x 60' Quadrangle Utah Department of Natural Resources 113°00'00" 112°52'30" 112°45'00" 112°37'30" 112°30'00" b E E E E E ! ! E ! E ! E E ! ! E E ! ! ! ! F ! E ! 38°15'00" ! ! 38°15'00" ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Tm (Ticl) QTs Qms *c ! Qal1 1 Ppk ! Qat ! Tm (Jn) E QTs Qal1 ! Qaf1 Qaf3 Tm (Tdv) Qat1 ! E ! E Qal1 Tm (Tlk) ! Pt M Tm (Tdv) ! Qaf ! E E 4 ! Qaf2 ! Qat1 E Qms A ! ! E ! E ! Qal1 Tm ! ! R ! Qal1 ! ! Tm ! E ! ! Qat1 ! Qaf1 31 K ! ! ! ! ! ! ^m ! ! A ! Pp ! 1 ! ! Qat ! (Tda) G ! ! ! ! ! (Tdv) ! E ! E ! E ! U ! ! ! E 1 E ! ! Qat ! ! ! N ! ! Tm (Tdv) ! ! ! ! E ! ! ! ! T ! ! QTs ! ! Qat2 2 ! Qaf ! ! Tm ! E E ! ! Qaf2 Tm (Tdv) ! ! ! Qaf1 Qat1 ! ! ! Tm (Tlk) ! E E ! ! E Tm (Ticl) ! ! Qat1 ! ! E ! ! ! ! ! ! (Tda) b ! Qat1 ! E ! ! Qaf3 ! ! ! Qaf1 ! ! E ! 7 ! E ! E ! ! ! ! Qaf3 Pt E 1 ! ! Qaf ! ! Tm (Tin) Tb Qat2 ! ! ! ! ^cm ! ! E E 1 ! ! ! Qaf ! Qaf2 Qaf3 ! ! ! E Qaf3 ! E ! Tm (Tlk) ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Ppk E ! ! E ! ! ! ! ! ! ! E 3 ! Qaf E Qaf3 ! ! 1 ! E Qaf ! ! E ! ! ! ! ! ! E ! ! ! ! Qaf1 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Tm (Tlb) ! ! ! ! ! E ! Tm (Tdb) ! ! ! ! E Tm ! ! ! E Qaf2 ! E ! ! Tm (Tda) E ! ! ! ! 2 ! ! Qaf Pq ! E ! ! ! E E ! ! E ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Tm (Tdv) E Qaf3 ! ! ! (Tin) ! Qaf2 ! ! ! E ! E ! Qaf2 E ! ! ! ! ! ! Qaf2 ! Tm (Tdv) ! ! ! ! ! E ! ! ! Tm E ! ! Qat1 ! ! Tm (Tdv) ! Qaf1 ! ! E ! ! ! ! E ! E ! Qal ! 2 ! ! ! E E! ! Tm (Tda) ! ! ! ! ! Tm (Tdv) ! ! ! ! ! ! E E E ! ! E ! ! ! ! Tm (Tdv) ! ! -

Geological Survey

DBPABTMBHT OF THE INTERIOR BULLETIN OF THK UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY No. 166 WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING- OFFICE 1.900 UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY (JHAKLES D. WALCOTT, DIKECTOK QAZETTEEE OF UTAH BY HENRY G-ANNETT WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT rilTNTING OFFICE 1900 ' \ CONTENTS Page. Letter of transmittal........................................................ 7 General description of the State ..........-................. -..- - ---- 9 Political history and area ............................................... 9 Exploration............................................................ 10 Settlement.......................................;..................... 12 Topography ........................................................... 12 Rivers................................................................. 13 Great Salt Lake ........................................................ 14 Elevation.............................................................. 15 Climate................................................................. 16 Population............................................................. 16 Industries .............................................................. 18 Counties.........'.............................................-......... 20 Gazetteer of the State....................................................... 21 ILLUSTRATIONS. PLATE I. Map of Utah...................................................... 9 FIG. 1. Historical map...................................................... 10 - 5 LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL. DEPARTMENT -

Ground -Water Conditions and Storage in the Central Sevier Valley

Groundr -Water Conditions and Storage in the Central Sevier Valley, Utah By RICHARD A. YOUNG and CARL H. CARPENTER GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1787 Prepared in cooperation with the Utah State Engineer PROPERTY OF U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GROUND WATER BRANCH TRENTON, N.J. UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1965 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 CONTENTS Page Abstract_ _______________________________________________________ 1 Introduction._____________________________________________________ 3 Purpose and scope of investigation_____________________________ 3 Location and extent of area____________________________________ 3 Previous work________________________________________________ 4 Personnel and methods of investigation___________---_-____--___ 4 Acknowledgments. ___ _ ______________________________________ 6 Well-numbering system__ ______________________________________ 6 Geography _____________________________________________________ 8 Physiography and drainage.____________________________________ 8 Climate._------_-_-----_-___---_---_--_--_-_-__----__--_-____ 9 Vegetation._ _ ________________________________________________ 10 Population, agriculture, and industry__--_-----__-------_-_------ 12 Geology._________________________________________________________ 12 Generalized stratigraphy________________________________________ 12 -

Ground-Water Resources of Selected Basins in Southwestern Utah

Utah State Engineer Technical PubUcation No. 13 GROUND-WATER RESOURCES OF SELECTED BASINS IN SOUTHWESTERN UTAH By G. W. Sandberg Hydraulic Engineer U. S. Geological Survey Prepared by the U. S. Geological Survey in cooperation with The Utah State Engineer 1966 CONTENTS Page Abstract _ __ _ _.................. 5 Introduotion _................................................................................................... 6 Purpose, scope, and method of investigation _... 6 Location __ _ _ 7 Previous investigations _............... 7 Topography and drainage _............... 7 Geology _..................... 9 Climate 9 Well-numbering system 11 Acknowledgements 11 Ground Water 11 Recharge __.. ___..__.. _ 11 Occurrence _............... 14 Movement _.................... 16 General pattern of movement _........... 16 Movement between valleys 17 Winn gap 17 Iron Springs gap _............................ 18 Twentymile gap _ _................. 18 Beaver River canyon ___ _........... 18 Change in pattern of movemenL.................................................... 18 Seasonal changes _ _................... 18 Long-term changes 19 Discharge , _ _..................... 19 Natural discharge _................................ 19 Springs and seeps __ _........... 19 Evaporation and transpiration.............................................. 20 Subsurface outflow _.. __ __ _................ 21 Discharge from wells __ _.......................... 21 Flowing wells _ 21 Pumped wells __ _._ _...................................... 21 Stock wells _._ _ -

The Geology of the Central Part of the Favant Range, Utah

THE GEOLOGY OF THE CENTRAL PART OF THE FAVANT RANGE, UTAH DISSERTATION sented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State Univers ity By HERMAN KENNETH LAUTENSCHLAGER, B • A. The Ohio State University 1952 Approved by: Adviser / 4 44 TABES OP CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION .......................... 1 LOCATION AND ACCESSIBILITY ..................... 2 FIELD WORK AND MAPPING ......................... 4 PREVIOUS WORK .................................... 5 PHYSICAL FEATURES ............................... 7 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................. 9 STRATIGRAPHY ......................................... 11 SEDIMENTARY R O C K S ........ 11 General Features <>............. 11 Cambrian System ..... 14 Tintic Quartzite 14 D e f i n i t i o n .............. 14 Distribution and 1ithology ....... 14 Stratigraphic relationships ..... 18 Age and correlation ............... 18 Ophir Formation ..... 20 D e f i n i t i o n ......................... 20 Distribution and 1ithology ..... 20 Stratigraphic relationships •••••• 20 Age and c o r r e l a t i o n ........ 21 Teutonic Limestone 21 Definition • . 21 Distribution and 1 ithology ...... 21 Stratigraphic relationships ...... 22 Age and correlation ........ 22 Dagmar Limestone ............ 23 Definition .................... 23 Distribution and 1ithology.*...... 23 Strat igraphie relat ionships ...... 24 Age and correlation ..... 24 i £ 0 9 4 2 8 Page Herkimer Limestone ...... 24 Definition ....................... 24 Distribution -

Fishlake National Forest Offer What’S Inside an Accessible Landscape for Anyone with a Sense of R Get to Know Us

ishlake National Forest F VISITOR GUIDE Blazing the Trail Fish Lake surrounded by fall colors Craggy cliff in the Tushar Mountains Beehive Peak area ising as an oasis in central Utah, the mountains and plateaus of the Fishlake National Forest offer What’s Inside an accessible landscape for anyone with a sense of R Get to Know Us ................. 2 adventure. Fish Lake, from which the forest takes Special Places ...................... 3 its name, is considered by many to be the gem of Scenic Byways ..................... 4 Utah. Many other scenic spots reveal secrets and Activities ............................... 4 stories of past settlements and civilizations. Map ......................................... 6 Campgrounds ..................... 8 Routes and Trails ....................................... 9 Fast Forest Facts trails on Know Before You Go.......10 the forest— Contact Information .......12 Elevation Range: 4,760’–12,120’ such as Acres: 1.5 million the nationally known Paiute ATV Trail system—are a means to access Miles of Designated OHV Trails: Over 3,000 miles of open roads opportunities such as hunting, fishing, and wildlife viewing. Camping is also Amazing Features: An aspen popular, but if you’d rather drive a stand near Fish Lake is considered the most massive living organism scenic byway or hike a trail on earth in solitude, we have those opportunities as well. Come see for yourself! This Visitor Guide provides the information you need to make the most of your Fishlake National Forest experience. G et to Know Us © Kapu History he resources of the Fishlake National Forest in central UtahT are vital to surrounding communities, a point not lost on President McKinley who reserved the first unit of the forest in 1899. -

Multiple Episodes of Igneous Activity, Mineralization, and Alteration in the Western Tushar Mountains, Utah

11 111 81111111:1111,. 1011,19111 3 1 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Multiple Episodes of Igneous Activity, Mineralization, and Alteration in the Western Tushar Mountains, Utah By Charles G. Cunningham, Thomas A. Steven, and Charles W. Naeser LOGICAL VA, JUN 0 21982 Open-File Report 82-479 1982 e Tt ) 0 9( *I Cespiogical I CONTENTS Page Abstract 1 Introduction 2 Geologic setting 2 Mineral deposits 7 Mineralized areas associated with the Bullion Canyon Volcanics 7 Mineralized areas associated with the Mount Belknap Volcanics 8 Late Miocene mineralized areas 10 Significance of reset isotopic ages 12 Summary 13 Acknowledgments 15 References 16 ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1. Index map showing location of calderas, major mining centers (starred), and principal altered and mineralized areas (stippled) in and adjacent to the Tushar Mountains 3 2. Geologic map of the western Tushar Mountains, Utah, showing areas of argillic and advanced argillic alteration, mineralized rocks, and sample localities 5 TABLES Table 1. Data for fission-track ages of rocks 6 2. Data for K-Ar ages of alunite 11 ABSTRACT Igneous activity in the Marysvale volcanic field of western Utah can be separated into many episodes of extrusion, intrusion, and hydrothermal activity. The rocks of the western Tushar Mountains, near the western part of the volcanic field, include early intermediate-composition calc-alkalic volcanic rocks erupted from scattered volcanoes in Oligocene through earliest Miocene time, and related monzonitic intrusions emplaced 24-23 m.y. ago. Beginning 22-21 m.y. ago and extending through much of the later Cenozoic, a bimodal basalt-rhyolite assemblage was erupted widely throughout the volcanic field. -

GEOLOGIC MAP of the RICHFIELD 30' X 60' QUADRANGLE

113°00' 3 0000m 112°00' R 10 W 3 E 1 600 1 600 00 FEET (SOUTH) R 9 W 34 3 3 3 4 R 21/2 W 1 850 000 FEET (CENTRAL) R 2 W 39°00' 1 625 1 625 45' R 8 W 1 650 1 675 1 675 R 7 W 6 1 700 1 700 R 6 W 30' 1 725 1 725 R 5 W 8 1 750 R 4 W 1 775 9 15' 1 800 1 800 R 3 W 0 1 825 1 825 39°00' -Cpm -Cdh 16 -Cdh Qaf2 QTaf Tf 55 Tf Qlg -Cp Tf Qdg Qdg Tht Qgt Tg 12 Qaf P Toc QTaf 1 -Cdh QTlf Qlf P - Qac 850 000 Qaf1 Qlg Qlg/Toc Toc Cum Kc Qal1 B -Cp -Cpm Qls Qgt FEET -Cpm 12 12 Qal1 Qac Qac Qgt Qac Tf Tse Tg Qaf2 - Qaf2 -Cop 18 -Cpm Cp Tf (SOUTH) Qla - Qla Jn TKn Cp Tf B Toc -Cpm 8 Qaf2 Tg -Cdh -Cdh QTlf Qdg Qlg -Cum 10 Qaf2 - Qaf2 QTaf - Cdh Toc TKn Tse Cpm -Cpm - -Cpm -Cdh Qdg Qed/Qvb3 Toc Qgt Qac Qac -Cpm Cp Tf QTlf Qla Qed/Qlf Qaf2 Toc -Cop Qed Qvb Qac B 1 Qac QTaf Qaf2 T 21 S -Cdh Toc Qaf2 QTaf QTaf -Cp 25 -Ccm Tf -Cdh TKn Qgt Qaf2 -Cp P -Cum Qal QTaf - -Cp QTlf Qac 1 B Cpm Toc Tg Tg Tflr Qaf2 T 21 S -Cdh -Cw Qed Qlf Qlg Qlg - 72 Tflr Qaf2 -Cp 12 Qla P Cum - - - -Cdh Qlf Qdg Qla Qmu Ct Cop Qac Tg Cw -Cp Tf Qaf1 Tflw - Tg Cp 11 -Cdh Tflr - -Cp TRm Qac Qac Cpm Qlg 5 -Ct Kc Qlg Qlf Toc Qaf 30 Tflr Tflw QTaf -Ccm 14 Qed/Qvb 2 - -Cdh QTlf 1 Toc TRcu Qac 10 Qac Cw B B Tht 20 TRcs 35 Qaf2 Tg 20 Qaf2 Qvb1 Kc 5 - Qlf/Qvb2 Qpm Tflr Tg Cdh - Qlg Qdf 30 Jn Qac QTaf -Cpm Cdh P -Cdh Qac -Cum TKn Qaf Qla P 20 Qaf2 1 - 18 Qed Qlg TRcu Tflr -Cpm Cdh Qed/Qlg Qed/Qlf Qed/ -Cum Qac 225 000 - -Ccm Qaf2 TRcs Qaf Cdh Qlf/ Tflr FEET 2 24 -Cw -Ccm Qed/Qll -Ccm QTlf Qed/ Qvb4 Qal2 30 Qac Qac -Cdh Qla Qed/Qvb1 Toc Tflw Tg (CENTRAL) Qdg Ktm 5 Qll Toc TRm Qac TKn Tg Qal B Qac -

Reconstruction of Late Pleistocene Paleoclimatic Characteristics in the Great Basin and Adjacent Areas

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Kenneth A. Bevis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geology presented on March 3. 1995. Title: Reconstruction of Late Pleistocene Paleoclimatic Characteristics in the Great Basin and Adjacent Areas Signature redacted for privacy. Abstract approved:. Peter U. Clark A sequence of glaciation based on relative dating parameters was established in each of nine mountain ranges located along a northwest to southeast transect through the northern Great Basin. Each sequence consists of two or three drift units. Degree of weathering suggests that the younger drift unit in a two-fold sequence and the intermediate drift unit in a three-fold sequence represents deposition during the late Pleistocene. The late Pleistocene equilibrium-line altitude (ELA) in each range was determined by reconstructing the maximum ice extent associated with these drift units and using the accumulation area ratio technique. Paleo-ELAs increase from about 2100 m in northeastern Oregon to approximately 3200 m in central Utah. Paleoclimatic conditions along the study transect were estimated by comparing modern climatic conditions at the reconstructed late Pleistocene ELAs with climatic conditions occurring at the ELAs of modem mid-latitude glaciers. Assuming no change in winter accumulation or in the seasonal distribution of precipitation from the present, a mean summer temperature depression ranging from about 9.0 °C at the northern end of the transect to about 4.0 °C at the southern end would have been necessary to sustain glaciers in these ranges during the late Pleistocene. To simulate possible changes in late Pleistocene precipitation patterns, a change in winter accumulation between 0.5 and 2.0 times the modem value resulted in a respective increase or decrease in temperature depression by approximately 2.0 °C. -

Copyright by Richard Ray Kennedy 1963 Geology of Piute County, Utah

Geology of Piute County, Utah Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic); maps Authors Kennedy, Richard R. (Richard Ray) Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 21:36:36 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/565611 COPYRIGHT BY RICHARD RAY KENNEDY 1963 GEOLOGY OF PIUTE COUNTY, UTAH by Richard Kennedy A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1963 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE I hereby recommend that this dissertation prepared under my direction by Richard R. Kennedy entitled "Geology of Piute County, Utah" be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. /P/o^Z 3 Dissertation Director Date After inspection of the dissertation, the following members of the Final Examination Committee concur in its approval and recommend its acceptance:* ♦This approval and acceptance is contingent on the candidate's adequate performance and defense of this dissertation at the final oral examina tion,, The inclusion of this sheet bound into the library copy of the dis sertation is evidence of satisfactory performance at the final examina tion. PLEASE NOTE: Figures and tables are not original copy. Some contain indistinct type. Filmed as received. -

MINERAL MAPPING in the MARYSVALE VOLCANIC FIELD, UTAH USING AVIRIS DATA Ger N

MINERAL MAPPING IN THE MARYSVALE VOLCANIC FIELD, UTAH USING AVIRIS DATA ger N. Clark, Charles G. Barnaby W. Rockwell, Roger N. Clark, Charles G. Cunningham, Stephen J. Sutley, Carol A. Gent, Robert R. McDougal, K. Eric Livo, and Raymond F. Kokaly United States Geological Survey Denver, Colorado http://speclab.cr.usgs.gov 1. Introduction This paper presents the results of AVIRIS-based mineral mapping in the Marysvale volcanic field, Sevier and Piute Counties, Utah. This work was performed as a part of the USGS-EPA Utah Abandoned Mine Lands (AML) Imaging Spectroscopy Project, in which spectroscopic imaging and analysis are being employed for watershed evaluation in areas of past and present mining activity. The project will map surface mineralogy to identify natural and man-made sources of acid generation as well as carbonate and chlorite-bearing lithologies which may provide acid buffering effects. Longer-term goals of the project include the application of the AVIRIS mineral maps to ore deposit studies and the generation of geo-environmental models for different ore deposit types. 2. Geologic Setting, Hydrothermal Alteration, and Ore Deposits The Marysvale volcanic field (Figure 1) is located in southwestern Utah in the High Plateaus transition zone between the Colorado Plateau and Basin and Range provinces. The field lies at the eastern end of the Pioche- Marysvale igneous belt which is comprised of Cenozoic igneous rocks and is underlain by a large batholith complex. This paper will focus on mineral mapping results obtained from the Antelope Range (Figure 2), a group of low hills located five kilometers northeast of the town of Marysvale.