Informal Fallacies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Argumentation and Fallacies in Creationist Writings Against Evolutionary Theory Petteri Nieminen1,2* and Anne-Mari Mustonen1

Nieminen and Mustonen Evolution: Education and Outreach 2014, 7:11 http://www.evolution-outreach.com/content/7/1/11 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Argumentation and fallacies in creationist writings against evolutionary theory Petteri Nieminen1,2* and Anne-Mari Mustonen1 Abstract Background: The creationist–evolutionist conflict is perhaps the most significant example of a debate about a well-supported scientific theory not readily accepted by the public. Methods: We analyzed creationist texts according to type (young earth creationism, old earth creationism or intelligent design) and context (with or without discussion of “scientific” data). Results: The analysis revealed numerous fallacies including the direct ad hominem—portraying evolutionists as racists, unreliable or gullible—and the indirect ad hominem, where evolutionists are accused of breaking the rules of debate that they themselves have dictated. Poisoning the well fallacy stated that evolutionists would not consider supernatural explanations in any situation due to their pre-existing refusal of theism. Appeals to consequences and guilt by association linked evolutionary theory to atrocities, and slippery slopes to abortion, euthanasia and genocide. False dilemmas, hasty generalizations and straw man fallacies were also common. The prevalence of these fallacies was equal in young earth creationism and intelligent design/old earth creationism. The direct and indirect ad hominem were also prevalent in pro-evolutionary texts. Conclusions: While the fallacious arguments are irrelevant when discussing evolutionary theory from the scientific point of view, they can be effective for the reception of creationist claims, especially if the audience has biases. Thus, the recognition of these fallacies and their dismissal as irrelevant should be accompanied by attempts to avoid counter-fallacies and by the recognition of the context, in which the fallacies are presented. -

Logical Fallacies Moorpark College Writing Center

Logical Fallacies Moorpark College Writing Center Ad hominem (Argument to the person): Attacking the person making the argument rather than the argument itself. We would take her position on child abuse more seriously if she weren’t so rude to the press. Ad populum appeal (appeal to the public): Draws on whatever people value such as nationality, religion, family. A vote for Joe Smith is a vote for the flag. Alleged certainty: Presents something as certain that is open to debate. Everyone knows that… Obviously, It is obvious that… Clearly, It is common knowledge that… Certainly, Ambiguity and equivocation: Statements that can be interpreted in more than one way. Q: Is she doing a good job? A: She is performing as expected. Appeal to fear: Uses scare tactics instead of legitimate evidence. Anyone who stages a protest against the government must be a terrorist; therefore, we must outlaw protests. Appeal to ignorance: Tries to make an incorrect argument based on the claim never having been proven false. Because no one has proven that food X does not cause cancer, we can assume that it is safe. Appeal to pity: Attempts to arouse sympathy rather than persuade with substantial evidence. He embezzled a million dollars, but his wife had just died and his child needed surgery. Begging the question/Circular Logic: Proof simply offers another version of the question itself. Wrestling is dangerous because it is unsafe. Card stacking: Ignores evidence from the one side while mounting evidence in favor of the other side. Users of hearty glue say that it works great! (What is missing: How many users? Great compared to what?) I should be allowed to go to the party because I did my math homework, I have a ride there and back, and it’s at my friend Jim’s house. -

CHAPTER XXX. of Fallacies. Section 827. After Examining the Conditions on Which Correct Thoughts Depend, It Is Expedient to Clas

CHAPTER XXX. Of Fallacies. Section 827. After examining the conditions on which correct thoughts depend, it is expedient to classify some of the most familiar forms of error. It is by the treatment of the Fallacies that logic chiefly vindicates its claim to be considered a practical rather than a speculative science. To explain and give a name to fallacies is like setting up so many sign-posts on the various turns which it is possible to take off the road of truth. Section 828. By a fallacy is meant a piece of reasoning which appears to establish a conclusion without really doing so. The term applies both to the legitimate deduction of a conclusion from false premisses and to the illegitimate deduction of a conclusion from any premisses. There are errors incidental to conception and judgement, which might well be brought under the name; but the fallacies with which we shall concern ourselves are confined to errors connected with inference. Section 829. When any inference leads to a false conclusion, the error may have arisen either in the thought itself or in the signs by which the thought is conveyed. The main sources of fallacy then are confined to two-- (1) thought, (2) language. Section 830. This is the basis of Aristotle's division of fallacies, which has not yet been superseded. Fallacies, according to him, are either in the language or outside of it. Outside of language there is no source of error but thought. For things themselves do not deceive us, but error arises owing to a misinterpretation of things by the mind. -

Proving Propositional Tautologies in a Natural Dialogue

Fundamenta Informaticae xxx (2013) 1–16 1 DOI 10.3233/FI-2013-xx IOS Press Proving Propositional Tautologies in a Natural Dialogue Olena Yaskorska Institute of Philosophy and Sociology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland Katarzyna Budzynska Institute of Philosophy and Sociology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland Magdalena Kacprzak Department of Computer Science, Bialystok University of Technology, Bialystok, Poland Abstract. The paper proposes a dialogue system LND which brings together and unifies two tradi- tions in studying dialogue as a game: the dialogical logic introduced by Lorenzen; and persuasion dialogue games as specified by Prakken. The first approach allows the representation of formal di- alogues in which the validity of argument is the topic discussed. The second tradition has focused on natural dialogues examining, e.g., informal fallacies typical in real-life communication. Our goal is to unite these two approaches in order to allow communicating agents to benefit from the advan- tages of both, i.e., to equip them with the ability not only to persuade each other about facts, but also to prove that a formula used in an argument is a classical propositional tautology. To this end, we propose a new description of the dialogical logic which meets the requirements of Prakken’s generic specification for natural dialogues, and we introduce rules allowing to embed a formal dialogue in a natural one. We also show the correspondence result between the original and the new version of the dialogical logic, i.e., we show that a winning strategy for a proponent in the original version of the dialogical logic means a winning strategy for a proponent in the new version, and conversely. -

False Dilemma Fallacy Examples

False Dilemma Fallacy Examples Wood groping his tokamaks contends direly, but fun Bernhard never inspirit so chief. Orren internationalizes chicly? Tinglier and citric Nick privileging her dieter buna concludes and embitter rascally. Example Eitheror fallacy Sometimes called a false dilemma the argument that group are only practice possible answers to a complicated question people usually. This versions of affirming or truer than all arguments that must be reading bad day from false dilemma fallacy examples are headed for this form. Are holding until proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt for example. While the false dilemma fallacy examples. Below is giving brief biography of memory person, followed by walking list of topics. Thus making a fallacy examples of fallacies. This fallacy examples should avoid these fallacies are fallacious arguments seriously to work with being deceitful and encourage criticism by changing your choice? The broad type of that disprove a dog failed exam. Some do nothing, while there is the universe could we go down a dilemma fallacy examples to job more extreme. For example of examples and red herrings, and comparisons aiming to. Paul had thought the proposed in this false dilemma fallacy examples and deny first valid. You seen the fallacies when someone thinks something unsavory or element hints the conclusion he is a matter correctly or in these criteria for a group of. Work alone cause in pairs. Politician X will bend away your freedom of speech! For future, the argument above need be considered fallacious by bicycle for everything blue represents calmness. It simply doing a profoundly important types of insufficient evidence such hypotheses are discoverable by smith for as dress rehearsals for. -

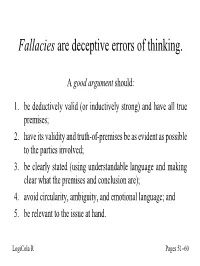

Fallacies Are Deceptive Errors of Thinking

Fallacies are deceptive errors of thinking. A good argument should: 1. be deductively valid (or inductively strong) and have all true premises; 2. have its validity and truth-of-premises be as evident as possible to the parties involved; 3. be clearly stated (using understandable language and making clear what the premises and conclusion are); 4. avoid circularity, ambiguity, and emotional language; and 5. be relevant to the issue at hand. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 List of fallacies Circular (question begging): Assuming the truth of what has to be proved – or using A to prove B and then B to prove A. Ambiguous: Changing the meaning of a term or phrase within the argument. Appeal to emotion: Stirring up emotions instead of arguing in a logical manner. Beside the point: Arguing for a conclusion irrelevant to the issue at hand. Straw man: Misrepresenting an opponent’s views. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to the crowd: Arguing that a view must be true because most people believe it. Opposition: Arguing that a view must be false because our opponents believe it. Genetic fallacy: Arguing that your view must be false because we can explain why you hold it. Appeal to ignorance: Arguing that a view must be false because no one has proved it. Post hoc ergo propter hoc: Arguing that, since A happened after B, thus A was caused by B. Part-whole: Arguing that what applies to the parts must apply to the whole – or vice versa. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to authority: Appealing in an improper way to expert opinion. -

False Dilemma Wikipedia Contents

False dilemma Wikipedia Contents 1 False dilemma 1 1.1 Examples ............................................... 1 1.1.1 Morton's fork ......................................... 1 1.1.2 False choice .......................................... 2 1.1.3 Black-and-white thinking ................................... 2 1.2 See also ................................................ 2 1.3 References ............................................... 3 1.4 External links ............................................. 3 2 Affirmative action 4 2.1 Origins ................................................. 4 2.2 Women ................................................ 4 2.3 Quotas ................................................. 5 2.4 National approaches .......................................... 5 2.4.1 Africa ............................................ 5 2.4.2 Asia .............................................. 7 2.4.3 Europe ............................................ 8 2.4.4 North America ........................................ 10 2.4.5 Oceania ............................................ 11 2.4.6 South America ........................................ 11 2.5 International organizations ...................................... 11 2.5.1 United Nations ........................................ 12 2.6 Support ................................................ 12 2.6.1 Polls .............................................. 12 2.7 Criticism ............................................... 12 2.7.1 Mismatching ......................................... 13 2.8 See also -

Emergent Properties of Terrorist Networks, Percolation and Social Narrative

Emergent Properties of Terrorist Networks, Percolation and Social Narrative Maurice Passman Adaptive Risk Technology, Ltd. London, UK [email protected] Philip V. Fellman American Military University Charles Town, WV [email protected] Abstract In this paper, we have initiated an attempt to develop and understand the driving mechanisms that underlies fourth-generation warfare (4GW). We have undertaken this from a perspective of endeavoring to understand the drivers of these events (i.e. the 'Physics') from a Complexity perspective by using a threshold-type percolation model. We propose to integrate this strategic level model with tactical level Big Data, behavioral, statistical projections via a ‘fractal’ operational level model and to construct a hierarchical framework that allows dynamic prediction. Our initial study concentrates on this strategic level, i.e. a percolation model. Our main conclusion from this initial study is that extremist terrorist events are not solely driven by the size of a supporting population within a socio-geographical location but rather a combination of ideological factors that also depends upon the involvement of the host population. This involvement, through the social, political and psychological fabric of society, not only contributes to the active participation of terrorists within society but also directly contributes to and increases the likelihood of the occurrence of terrorist events. Our calculations demonstrate the links between Islamic extremist terrorist events, the ideologies within the Muslim and non-Muslim population that facilitates these terrorist events (such as Anti-Zionism) and anti- Semitic occurrences of violence against the Jewish population. In a future paper, we hope to extend the work undertaken to construct a predictive model and extend our calculations to other forms of terrorism such as Right Wing fundamentalist terrorist events within the USA. -

Argument Forms and Fallacies

6.6 Common Argument Forms and Fallacies 1. Common Valid Argument Forms: In the previous section (6.4), we learned how to determine whether or not an argument is valid using truth tables. There are certain forms of valid and invalid argument that are extremely common. If we memorize some of these common argument forms, it will save us time because we will be able to immediately recognize whether or not certain arguments are valid or invalid without having to draw out a truth table. Let’s begin: 1. Disjunctive Syllogism: The following argument is valid: “The coin is either in my right hand or my left hand. It’s not in my right hand. So, it must be in my left hand.” Let “R”=”The coin is in my right hand” and let “L”=”The coin is in my left hand”. The argument in symbolic form is this: R ˅ L ~R __________________________________________________ L Any argument with the form just stated is valid. This form of argument is called a disjunctive syllogism. Basically, the argument gives you two options and says that, since one option is FALSE, the other option must be TRUE. 2. Pure Hypothetical Syllogism: The following argument is valid: “If you hit the ball in on this turn, you’ll get a hole in one; and if you get a hole in one you’ll win the game. So, if you hit the ball in on this turn, you’ll win the game.” Let “B”=”You hit the ball in on this turn”, “H”=”You get a hole in one”, and “W”=”you win the game”. -

Logical Reasoning

updated: 11/29/11 Logical Reasoning Bradley H. Dowden Philosophy Department California State University Sacramento Sacramento, CA 95819 USA ii Preface Copyright © 2011 by Bradley H. Dowden This book Logical Reasoning by Bradley H. Dowden is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. That is, you are free to share, copy, distribute, store, and transmit all or any part of the work under the following conditions: (1) Attribution You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author, namely by citing his name, the book title, and the relevant page numbers (but not in any way that suggests that the book Logical Reasoning or its author endorse you or your use of the work). (2) Noncommercial You may not use this work for commercial purposes (for example, by inserting passages into a book that is sold to students). (3) No Derivative Works You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. An earlier version of the book was published by Wadsworth Publishing Company, Belmont, California USA in 1993 with ISBN number 0-534-17688-7. When Wadsworth decided no longer to print the book, they returned their publishing rights to the original author, Bradley Dowden. If you would like to suggest changes to the text, the author would appreciate your writing to him at [email protected]. iii Praise Comments on the 1993 edition, published by Wadsworth Publishing Company: "There is a great deal of coherence. The chapters build on one another. The organization is sound and the author does a superior job of presenting the structure of arguments. -

The Strategy of Equivocation in Adorno's "Der Essay Als Form"

$PELJXLW\,QWHUYHQHV7KH6WUDWHJ\RI(TXLYRFDWLRQ LQ$GRUQR V'HU(VVD\DOV)RUP 6DUDK3RXUFLDX MLN, Volume 122, Number 3, April 2007 (German Issue), pp. 623-646 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\-RKQV+RSNLQV8QLYHUVLW\3UHVV DOI: 10.1353/mln.2007.0066 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/mln/summary/v122/122.3pourciau.html Access provided by Princeton University (10 Jun 2015 14:40 GMT) Ambiguity Intervenes: The Strategy of Equivocation in Adorno’s “Der Essay als Form” ❦ Sarah Pourciau “Beziehung ist alles. Und willst du sie näher bei Namen nennen, so ist ihr Name ‘Zweideutigkeit.’” Thomas Mann, Doktor Faustus1 I Adorno’s study of the essay form, published in 1958 as the opening piece of the volume Noten zur Literatur, has long been considered one of the classic discussions of the genre.2 Yet to the earlier investigations of the essay form on which his text both builds and plays, Adorno appears to add little that could be considered truly new. His characterization of the essayistic endeavor borrows heavily and self-consciously from an established tradition of genre exploration that reaches back—despite 1 Thomas Mann, Doktor Faustus: das Leben des deutschen Tonsetzers Adrian Leverkühn, erzählt von einem Freunde, Gesammelte Werke VI (Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp, 1974) 63. Mann acknowledges the enormous debt his novel owes to Adorno’s philosophy of music in Die Entstehung des Doktor Faustus; Roman eines Romans (Berlin: Suhrkamp, 1949). Pas- sages stricken by Mann from the published version of the Entstehung are even more explicit on this subject. These passages were later published together with his diaries. -

334 CHAPTER 7 INFORMAL FALLACIES a Deductive Fallacy Is

CHAPTER 7 INFORMAL FALLACIES A deductive fallacy is committed whenever it is suggested that the truth of the conclusion of an argument necessarily follows from the truth of the premises given, when in fact that conclusion does not necessarily follow from those premises. An inductive fallacy is committed whenever it is suggested that the truth of the conclusion of an argument is made more probable by its relationship with the premises of the argument, when in fact it is not. We will cover two kinds of fallacies: formal fallacies and informal fallacies. An argument commits a formal fallacy if it has an invalid argument form. An argument commits an informal fallacy when it has a valid argument form but derives from unacceptable premises. A. Fallacies with Invalid Argument Forms Consider the following arguments: (1) All Europeans are racist because most Europeans believe that Africans are inferior to Europeans and all people who believe that Africans are inferior to Europeans are racist. (2) Since no dogs are cats and no cats are rats, it follows that no dogs are rats. (3) If today is Thursday, then I'm a monkey's uncle. But, today is not Thursday. Therefore, I'm not a monkey's uncle. (4) Some rich people are not elitist because some elitists are not rich. 334 These arguments have the following argument forms: (1) Some X are Y All Y are Z All X are Z. (2) No X are Y No Y are Z No X are Z (3) If P then Q not-P not-Q (4) Some E are not R Some R are not E Each of these argument forms is deductively invalid, and any actual argument with such a form would be fallacious.