Vol.21 No.4 April 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN: Life-Story, Letters, and Reminiscences

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com SirArthurSullivan ArthurLawrence,BenjaminWilliamFindon,WilfredBendall \ SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN: Life-Story, Letters, and Reminiscences. From the Portrait Pruntfd w 1888 hv Sir John Millais. !\i;tn;;;i*(.vnce$. i-\ !i. W. i ind- i a. 1 V/:!f ;d B'-:.!.i;:. SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN : Life-Story, Letters, and Reminiscences. By Arthur Lawrence. With Critique by B. W. Findon, and Bibliography by Wilfrid Bendall. London James Bowden 10 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden, W.C. 1899 /^HARVARD^ UNIVERSITY LIBRARY NOV 5 1956 PREFACE It is of importance to Sir Arthur Sullivan and myself that I should explain how this book came to be written. Averse as Sir Arthur is to the " interview " in journalism, I could not resist the temptation to ask him to let me do something of the sort when I first had the pleasure of meeting ^ him — not in regard to journalistic matters — some years ago. That permission was most genially , granted, and the little chat which I had with J him then, in regard to the opera which he was writing, appeared in The World. Subsequent conversations which I was privileged to have with Sir Arthur, and the fact that there was nothing procurable in book form concerning our greatest and most popular composer — save an interesting little monograph which formed part of a small volume published some years ago on English viii PREFACE Musicians by Mr. -

Vol. 17, No. 4 April 2012

Journal April 2012 Vol.17, No. 4 The Elgar Society Journal The Society 18 Holtsmere Close, Watford, Herts., WD25 9NG Email: [email protected] April 2012 Vol. 17, No. 4 President Editorial 3 Julian Lloyd Webber FRCM ‘... unconnected with the schools’ – Edward Elgar and Arthur Sullivan 4 Meinhard Saremba Vice-Presidents The Empire Bites Back: Reflections on Elgar’s Imperial Masque of 1912 24 Ian Parrott Andrew Neill Sir David Willcocks, CBE, MC Diana McVeagh ‘... you are on the Golden Stair’: Elgar and Elizabeth Lynn Linton 42 Michael Kennedy, CBE Martin Bird Michael Pope Book reviews 48 Sir Colin Davis, CH, CBE Lewis Foreman, Carl Newton, Richard Wiley Dame Janet Baker, CH, DBE Leonard Slatkin Music reviews 52 Sir Andrew Davis, CBE Julian Rushton Donald Hunt, OBE DVD reviews 54 Christopher Robinson, CVO, CBE Richard Wiley Andrew Neill Sir Mark Elder, CBE CD reviews 55 Barry Collett, Martin Bird, Richard Wiley Letters 62 Chairman Steven Halls 100 Years Ago 65 Vice-Chairman Stuart Freed Treasurer Peter Hesham Secretary The Editor does not necessarily agree with the views expressed by contributors, Helen Petchey nor does the Elgar Society accept responsibility for such views. Front Cover: Arthur Sullivan: specially engraved for Frederick Spark’s and Joseph Bennett’s ‘History of the Leeds Musical Festivals’, (Leeds: Fred. R. Spark & Son, 1892). Notes for Contributors. Please adhere to these as far as possible if you deliver writing (as is much preferred) in Microsoft Word or Rich Text Format. A longer version is available in case you are prepared to do the formatting, but for the present the editor is content to do this. -

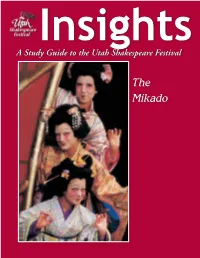

The Mikado the Articles in This Study Guide Are Not Meant to Mirror Or Interpret Any Productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

Insights A Study Guide to the Utah Shakespeare Festival The Mikado The articles in this study guide are not meant to mirror or interpret any productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival. They are meant, instead, to be an educational jumping-off point to understanding and enjoying the plays (in any production at any theatre) a bit more thoroughly. Therefore the stories of the plays and the interpretative articles (and even characters, at times) may differ dramatically from what is ultimately produced on the Festival’s stages. Insights is published by the Utah Shakespeare Festival, 351 West Center Street; Cedar City, UT 84720. Bruce C. Lee, communications director and editor; Phil Hermansen, art director. Copyright © 2011, Utah Shakespeare Festival. Please feel free to download and print Insights, as long as you do not remove any identifying mark of the Utah Shakespeare Festival. For more information about Festival education programs: Utah Shakespeare Festival 351 West Center Street Cedar City, Utah 84720 435-586-7880 www.bard.org. Cover photo: Erin Annarella (top), Carol Johnson, and Sarah Dammann in The Mikado, 1996 Contents Information on the Play Synopsis 4 CharactersThe Mikado 5 About the Playwright 6 Scholarly Articles on the Play Mere Pish-Posh 8 Utah Shakespeare Festival 3 351 West Center Street • Cedar City, Utah 84720 • 435-586-7880 Synopsis: The Mikado Nanki-Poo, the son of the royal mikado, arrives in Titipu disguised as a peasant and looking for Yum- Yum. Without telling the truth about who he is, Nanki-Poo explains that several months earlier he had fallen in love with Yum-Yum; however she was already betrothed to Ko-Ko, a cheap tailor, and he saw that his suit was hopeless. -

The Elgar Sketch-Books

THE ELGAR SKETCH-BOOKS PAMELA WILLETTS A MAJOR gift from Mrs H. S. Wohlfeld of sketch-books and other manuscripts of Sir Edward Elgar was received by the British Library in 1984. The sketch-books consist of five early books dating from 1878 to 1882, a small book from the late 1880s, a series of eight volumes made to Elgar's instructions in 1901, and two later books commenced in Italy in 1909.^ The collection is now numbered Add. MSS. 63146-63166 (see Appendix). The five early sketch-books are oblong books in brown paper covers. They were apparently home-made from double sheets of music-paper, probably obtained from the stock of the Elgar shop at 10 High Street, Worcester. The paper was sewn together by whatever means was at hand; volume III is held together by a gut violin string. The covers were made by the expedient of sticking brown paper of varying shades and textures to the first and last leaves of music-paper and over the spine. Book V is of slightly smaller oblong format and the sides of the music sheets in this volume have been inexpertly trimmed. The volumes bear Elgar's numbering T to 'V on the covers, his signature, and a date, perhaps that ofthe first entry in the volumes. The respective dates are: 21 May 1878(1), 13 August 1878 (II), I October 1878 (III), 7 April 1879 (IV), and i September 1881 (V). Elgar was not quite twenty-one when the first of these books was dated. Earlier music manuscripts from his hand have survived but the particular interest of these early sketch- books is in their intimate connection with the round of Elgar's musical activities, amateur and professional, at a formative stage in his career. -

April 2021 Vol.22, No. 4 the Elgar Society Journal 37 Mapledene, Kemnal Road, Chislehurst, Kent, BR7 6LX Email: [email protected]

Journal April 2021 Vol.22, No. 4 The Elgar Society Journal 37 Mapledene, Kemnal Road, Chislehurst, Kent, BR7 6LX Email: [email protected] April 2021 Vol. 22, No. 4 Editorial 3 President Sir Mark Elder, CH, CBE Ballads and Demons: a context for The Black Knight 5 Julian Rushton Vice-President & Past President Julian Lloyd Webber Elgar and Longfellow 13 Arthur Reynolds Vice-Presidents Diana McVeagh Four Days in April 1920 23 Dame Janet Baker, CH, DBE Some notes regarding the death and burial of Alice Elgar Leonard Slatkin Relf Clark Sir Andrew Davis, CBE Christopher Robinson, CVO, CBE Book reviews 36 Andrew Neill Arthur Reynolds, Relf Clark Martyn Brabbins Tasmin Little, OBE CD Reviews 44 Christopher Morley, Neil Mantle, John Knowles, Adrian Brown, Chairman Tully Potter, Andrew Neill, Steven Halls, Kevin Mitchell, David Morris Neil Mantle, MBE DVD Review 58 Vice-Chairman Andrew Keener Stuart Freed 100 Years Ago... 60 Treasurer Kevin Mitchell Peter Smith Secretary George Smart The Editors do not necessarily agree with the views expressed by contributors, nor does the Elgar Society accept responsibility for such views. Front Cover: Portrait photograph of Longfellow taken at ‘Freshfields’, Isle of Wight in 1868 by Julia Margaret Cameron. Courtesy National Park Service, Longfellow Historical Site. Notes for Contributors. Please adhere to these as far as possible if you deliver writing (as is much Editorial preferred) in Microsoft Word or Rich Text Format. Copyright: it is the contributor’s responsibility to be reasonably sure that copyright permissions, if required, are obtained. Professor Russell Stinson, the musicologist, in his chapter on Elgar in his recently issued Bach’s Legacy (reviewed in this issue) states that Elgar had ‘one of the greatest minds in English music’.1 Illustrations (pictures, short music examples) are welcome, but please ensure they are pertinent, This is a bold claim when considering the array of intellectual ability in English music ranging cued into the text, and have captions. -

Or, the Witch's Curse!

Ruddygore or, The Witch's Curse! An Entirely Original Supernatural Opera in Two Acts Written by W. S. Gilbert Composed by Arthur Sullivan First produced at the Savoy Theatre, London, Saturday 22nd January 1887 under the management of Mr. Richard D'Oyly Carte This edition privately published by Ian C. Bond at 2 Kentisview, Kentisbeare, CULLOMPTON. EX15 2BS. © 1995 RUDDYGORE Of all the Gilbert and Sullivan joint works, RUDDYGORE has been the most unfairly treated. The initial, rather hostile reception, led the partners to make a number of cuts and changes which, under rather more favourable circumstances, would probably not have been so severe. This gradual dissection continued in the 1920’s at the hands of Geoffrey Toye, Harry Norris, Malcolm Sargent and J M Gordon until, by the post-war revival of 1949, RUDDIGORE was, to all intents and purposes, a new work. It is to be hoped that such a thing could not happen today as I would like to think that we have far too much respect for the works of these two men to allow anyone to take such drastic rewrites upon themselves. That the original version of the opera works is evidenced by the considerable number of amateur revivals over the past few years that have attempted to return as closely as possible (given the lack of performing material) to a ‘first night version’ - a trend fuelled by the New Sadler’s Wells revival of 1987. That Gilbert was guilty of one miscalculation is fairly obvious in his placing of “The battle’s roar is over” in Act One. -

The Death of Christian Culture

Memoriœ piœ patris carrissimi quoque et matris dulcissimœ hunc libellum filius indignus dedicat in cordibus Jesu et Mariœ. The Death of Christian Culture. Copyright © 2008 IHS Press. First published in 1978 by Arlington House in New Rochelle, New York. Preface, footnotes, typesetting, layout, and cover design copyright 2008 IHS Press. Content of the work is copyright Senior Family Ink. All rights reserved. Portions of chapter 2 originally appeared in University of Wyoming Publications 25(3), 1961; chapter 6 in Gary Tate, ed., Reflections on High School English (Tulsa, Okla.: University of Tulsa Press, 1966); and chapter 7 in the Journal of the Kansas Bar Association 39, Winter 1970. No portion of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review, or except in cases where rights to content reproduced herein is retained by its original author or other rights holder, and further reproduction is subject to permission otherwise granted thereby according to applicable agreements and laws. ISBN-13 (eBook): 978-1-932528-51-0 ISBN-10 (eBook): 1-932528-51-2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Senior, John, 1923– The death of Christian culture / John Senior; foreword by Andrew Senior; introduction by David Allen White. p. cm. Originally published: New Rochelle, N.Y. : Arlington House, c1978. ISBN-13: 978-1-932528-51-0 1. Civilization, Christian. 2. Christianity–20th century. I. Title. BR115.C5S46 2008 261.5–dc22 2007039625 IHS Press is the only publisher dedicated exclusively to the social teachings of the Catholic Church. -

UC Santa Barbara Dissertation Template

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara English Reception of Felix Mendelssohn as Told Through British Music Histories A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Linda Joann Shaver-Gleason Committee in charge: Professor Derek Katz, Chair Professor David Paul Professor Stefanie Tcharos September 2016 The dissertation of Linda Joann Shaver-Gleason is approved. ____________________________________________ David Paul ____________________________________________ Stefanie Tcharos ____________________________________________ Derek Katz, Committee Chair September 2016 English Reception of Felix Mendelssohn as Told Through British Music Histories Copyright © 2016 by Linda Joann Shaver-Gleason iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I must first acknowledge my own mortality. During the course of writing this dissertation, I was diagnosed with stage IV breast cancer which had spread to my spine. I spent weeks in the hospital and months afterward mostly bedridden. So, I owe a debt of gratitude to oncologists Juliet Penn and James Waisman for finding a chemotherapy that fights my tumors while keeping the side effects manageable enough for me to work. A warm thank you to the folks at the Solvang Cancer Center who take care of me during chemo sessions, and thank you also to the people at Santa Barbara Cottage Hospital, Santa Ynez Valley Cottage Hospital, Lompoc Valley Medical Center, City of Hope, and Sansum Clinic Lompoc. Without them, I would not be around to thank anyone else. Thank you to my family who helped out during this difficult time, particularly my parents, Carl and Patricia Shaver; my sister-in-law, Andrea Langham; and my niece, Daisy Langham. Thank you also to Ellen and Rich Krasin, Ruth and Steve Marotti, Shirley Shaver, Mary Lou Trocke, Jim and Cindy Gleason, and Ralph Lincoln. -

The Muse of Fire: Liberty and War Songs As a Source of American History

3 7^ A'£?/</ THE MUSE OF FIRE: LIBERTY AND WAR SONGS AS A SOURCE OF AMERICAN HISTORY DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Kent Adam Bowman, B.A., M.A Denton, Texas August, 1984 Bowman, Kent Adam, The Muse of Fire; Liberty and War Songs as a Source of American History. Doctor of Philosophy (History), August, 1984, 337 pp., bibliography, 135 titles. The development of American liberty and war songs from a few themes during the pre-Revolutionary period to a distinct form of American popular music in the Civil War period reflects the growth of many aspects of American culture and thought. This study therefore treats as historical documents the songs published in newspapers, broadsides, and songbooks during the period from 1765 to 1865. Chapter One briefly summarizes the development of American popular music before 1765 and provides other introductory material. Chapter Two examines the origin and development of the first liberty-song themes in the period from 1765 to 1775. Chapters Three and Four cover songs written during the American Revolution. Chapter Three describes battle songs, emphasizing the use of humor, and Chapter Four examines the figures treated in the war song. Chapter Five covers the War of 1812, concentrating on the naval song, and describes the first use of dialect in the American war song. Chapter Six covers the Mexican War (1846-1848) and includes discussion of the aggressive American attitude toward the war as evidenced in song. -

Nonatonic Harmonic Structures in Symphonies by Ralph Vaughan Williams and Arnold Bax Cameron Logan [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 12-2-2014 Nonatonic Harmonic Structures in Symphonies by Ralph Vaughan Williams and Arnold Bax Cameron Logan [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Logan, Cameron, "Nonatonic Harmonic Structures in Symphonies by Ralph Vaughan Williams and Arnold Bax" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 603. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/603 i Nonatonic Harmonic Structures in Symphonies by Ralph Vaughan Williams and Arnold Bax Cameron Logan, Ph.D. University of Connecticut, 2014 This study explores the pitch structures of passages within certain works by Ralph Vaughan Williams and Arnold Bax. A methodology that employs the nonatonic collection (set class 9-12) facilitates new insights into the harmonic language of symphonies by these two composers. The nonatonic collection has received only limited attention in studies of neo-Riemannian operations and transformational theory. This study seeks to go further in exploring the nonatonic‟s potential in forming transformational networks, especially those involving familiar types of seventh chords. An analysis of the entirety of Vaughan Williams‟s Fourth Symphony serves as the exemplar for these theories, and reveals that the nonatonic collection acts as a connecting thread between seemingly disparate pitch elements throughout the work. Nonatonicism is also revealed to be a significant structuring element in passages from Vaughan Williams‟s Sixth Symphony and his Sinfonia Antartica. A review of the historical context of the symphony in Great Britain shows that the need to craft a work of intellectual depth, simultaneously original and traditional, weighed heavily on the minds of British symphonists in the early twentieth century. -

Precious Nonsense

Precious Nonsense NEWSLETTER OF THE MIDWESTERN GILBERT AND SULLIVAN SOCIETY March 1992 -- Issue 33 ✠★✡ ✠★✡ ✠★✡ ✠★✡ ✠★✡ ✠★✡ ✠★✡ ✠★✡ Her honeymoon With that buffoon At seven commences, so you shun her! Although this isn't June, this seems to be the season for engagements and brides (see the "Oh, Members" section for an explanation). There is also a wedding afoot in the Cole household: S/A Cole's brother is getting married, so for the past two months she has been occupied with helping make arrangements. That's why the Nonsense was delayed (again). But we tried to make it worth the wait. We have a couple of book reviews, a lot of production announcements, the long, long delayed Membership Cards, and even a couple of prize giveaways. So let's toddle away, with or without the Lord High Executioner. ✠★✡ ✠★✡ ✠★✡ ✠★✡ ✠★✡ ✠★✡ ✠★✡ ✠★✡ Oh, Members, How Say You, What is it What Cheer! What Cheer! {Midwest- You've Done? ern} Jeordano Martinez was responsible for the ac- Hugh Locker has reported that the Chicago radio claimed production of Mikado recently presented at station WFMT (98.7 FM) is going to be airing a com- North Central College in Naperville (Illinois). As far as plete survey of the Gilbert and Sullivan Operas during we know, this was the first substantial G&S performance April, at 1:00 on Thursday afternoons. Some of you to take place at North Central College since the 1970's, may remember a talk given at the Basingstoke! G&S so it was nice to see a return to the classics. Weekend in 1989, where the presenter lamented the fact that so little G&S was broadcast in the Chicago area. -

Elgar Organ Works

THE DOBSON ORGAN OF MERTON COLLEGE, OXFORD Elgar BENJAMIN NICHOLAS Organ wor ks EDWARD ELGAR (1857–1934): ORGAN WORKS THE DOBSON ORGAN OF MERTON COLLEGE, OXFORD Sonata for Organ in G major, Op. 28 Benjamin Nicholas 1 I. Allegro maestoso [9:03] 2 II. Allegretto [4:37] 3 III. Andante espressivo [6:31] 4 IV. Presto (comodo) [7:05] 5 ‘Nimrod’ from ‘Enigma’ Variations, Op. 36 [3:56] transcr. by W. H. Harris 6 Prelude to The Kingdom, Op. 51 [9:43] transcr. by A. Herbert Brewer* 7 Gavotte [5:50] transcr. by Edwin H. Lemare Vesper Voluntaries, Op. 14 8 Introduction: Adagio – [1:33] 9 I. Andante [1:20] 10 II. Allegro [2:57] 11 III. Andantino [2:42] 12 IV. Allegretto piacevole [1:56] 13 Intermezzo [0:44] 14 V. Poco lento [2:03] 15 VI. Moderato [1:57] 16 VII. Allegretto pensoso [2:00] 17 VIII. Poco allegro – Coda [4:27] Recorded on 25-26 June 2015 in Cover design: John Christ Join the Delphian mailing list: the Chapel of Merton College, Oxford Booklet design: Drew Padrutt www.delphianrecords.co.uk/join Total playing time [68:33] Producer/Engineer: Paul Baxter Benjamin Nicholas photo: John Cairns 24-bit digital editing: Adam Binks Booklet editor: John Fallas Like us on Facebook: 24-bit digital mastering: Paul Baxter Delphian Records Ltd – Edinburgh – UK www.facebook.com/delphianrecords *premiere recording of this arrangement Cover & booklet photography © Dobson www.delphianrecords.co.uk Pipe Organ Builders Ltd Follow us on Twitter: @delphianrecords With thanks to the Warden and Fellows of the House of Scholars of Merton College, Oxford Notes on the music The first recording of Merton’s new organ – post of Organist and Choirmaster in his own offering music and seeking commissions with attractively individual, quirky charm.