A Content Analysis of Russia's Coverage in Cnn News Programs, 1993 - 1997

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ed 382 185 Title Institution Pub Date Note Available From

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 382 185 IR 017 126 TITLE CNN Newsroom Classroom Guirles. May 1-31, 1995. INSTITUTION Cable News Network, Atlanta, GA.; Turner Educational Services, Inc., Atlanta, GA. PUB DATE 95 NOTE 90p.; Videos of the broadcasts can be ordered from CNN. AVAILABLE FROMAvailable electronically through gopher at: [email protected]. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Cable Television; *Class Activities; *Current Events; Discussion (Teaching Technique); *Educational Television; Elementary Secondary Education; *News Media; Programming (Broadcast); *Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Cable News Network; *CNN Newsroom ABSTRACT These classroom guides for the daily CNN (Cable News Network) Newsroom broadcasts for the month of May provide program rundowns, suggestions for class activities and discussion, student handouts, and a list of related news terms. Topics covered by the guide include:(1) security systems and security at the Olympics, drawing to scale, civil war in Algeria, Sri Lankan tea and tea tasting, heart disease/heart health, kinds of news stories, and create-a-headline (May 1-5);(2) blue screen technology and virtual reality, 50th anniversary of V-E Day, Nazi Germany,Clinton/Yeltsin meeting, African-American summit, a "Marshall Plan" for Africa's economic recovery, trapping termites, parenthood, and perspectives on V-E Day (May 8-12); (3) experimental/future transportation, human diseases, new Zulu wars, first year of the Mandela administration, pet ownership, -

History Early History

Cable News Network, almost always referred to by its initialism CNN, is a U.S. cable newsnetwork founded in 1980 by Ted Turner.[1][2] Upon its launch, CNN was the first network to provide 24-hour television news coverage,[3] and the first all-news television network in the United States.[4]While the news network has numerous affiliates, CNN primarily broadcasts from its headquarters at the CNN Center in Atlanta, the Time Warner Center in New York City, and studios in Washington, D.C. and Los Angeles. CNN is owned by parent company Time Warner, and the U.S. news network is a division of the Turner Broadcasting System.[5] CNN is sometimes referred to as CNN/U.S. to distinguish the North American channel from its international counterpart, CNN International. As of June 2008, CNN is available in over 93 million U.S. households.[6] Broadcast coverage extends to over 890,000 American hotel rooms,[6] and the U.S broadcast is also shown in Canada. Globally, CNN programming airs through CNN International, which can be seen by viewers in over 212 countries and territories.[7] In terms of regular viewers (Nielsen ratings), CNN rates as the United States' number two cable news network and has the most unique viewers (Nielsen Cume Ratings).[8] History Early history CNN's first broadcast with David Walkerand Lois Hart on June 1, 1980. Main article: History of CNN: 1980-2003 The Cable News Network was launched at 5:00 p.m. EST on Sunday June 1, 1980. After an introduction by Ted Turner, the husband and wife team of David Walker and Lois Hart anchored the first newscast.[9] Since its debut, CNN has expanded its reach to a number of cable and satellite television networks, several web sites, specialized closed-circuit networks (such as CNN Airport Network), and a radio network. -

AU Alumni Share Their Experiences in the 2016 Elections Anne Caprara

Tales from the Trail: AU Alumni Share Their Experiences in the 2016 Elections Tuesday, November 15th at American University ( Mary Graydon Center) Anne Caprara currently serves as the Executive Director for Priorities USA Action, the main Super PAC supporting Hillary Clinton for President. Before coming to Priorities, Anne served as the Vice President of Campaigns at EMILY’s List. In 2014, Anne was political director for the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee, helping to oversee Senate races in 33 states. In 2011 and 2012, Anne served as the DSCC’s Deputy Political Director, covering all Senate races east of Wisconsin. She spent the last weeks of the 2012 cycle working in Connecticut to help defeat Republican Senate candidate Linda McMahon. In 2008, Anne was the campaign manager for Betsy Markey, a first time candidate running against a 3-term Republican Congresswoman in Colorado’s 4th congressional district. Betsy won by the race by 12 points and Anne subsequently served as Betsy’s chief of staff from 2008 until 2010. Previous to that, Anne served as Chief of Staff for Ohio Congresswoman Betty Sutton and as the Deputy Research Director at EMILY’s List. She obtained her Master's degree from George Washington University and her undergraduate degree from American University. Richard Davis is CNN's executive vice president of News Standards and Practices. In this capacity, Davis works to ensure that CNN Worldwide's on-air reports and programs are fair, accurate and responsible. He was named to this position in July 1998. He is based in CNN's world headquarters in Atlanta.Davis previously served for eight years as CNN's vice president and senior executive producer for Washington Public Affairs Programs. -

{Replace with the Title of Your Dissertation}

Gendered Voices: Rhetorical Agency and the Political Career of Hillary Rodham Clinton A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Justin Lee Killian IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Karlyn Kohrs Campbell, Ph.D. (Adviser) August 2012 © Justin Lee Killian 2012 Acknowledgments As a critic, I seek to understand how agency is created by the phrases we write and the words we speak. I love language, and these pages are my attempt to make sense of voice, rhetoric, and politics. The insightful ideas in this project come from the beautiful voices of my friends and family. The mistakes and blunders are all mine. I am blessed by the love of so many wonderful people, and I offer these acknowledgments as a small gesture of gratitude to all who have touched this project. As an academic, I am most indebted to Karlyn Kohrs Campbell for her faith and guidance. She nurtured this project from the beginning, and she was the driving force that helped push me over innumerable stumbling points. I am so glad she offered tough love and refused to let me stop fighting. I can only hope that my work in some way answers the important call Dr. Campbell has issued to the field of rhetorical studies. I am honored that she gave me her time and dedication. She will forever be my mentor and teacher. I also give thanks to the other members of my review committee. I am very grateful to the guidance provided by Edward Schiappa. -

Hourglass 02-27-04.Indd

Inside: Students set record for science fair — page 3 A wounded soldier’s story Where can this — page 6 WWII ‘Ace’ teacher go to recounts school? ‘Tuskegee — pages 4-5 experiment ‘ — page 7 Feb. 27, 2004 The Kwajalein(Photo Hourglass by KW Hillis) Editorial Letters to the Editor and again in 2002. he had to endure the merciless rib- Hourglass wins at Also this year, Assistant Editor bing of his co-workers. Neither of us SMDC contest Karen Hillis took first place in the had a light. Dear readers, Writer Contractor/Stringer category We all know that Kwajalein is a It’s my honor tell you that The for her articles: “Laura farmers prep safe place to live, work, and play, Hourglass has done it again! The for Kwaj tables,“ “WUTMI group for- and with the small amount of ve- staff recently competed in the first wards recommendations on issues,“ hicle traffic and the low speed limits phase of the Army’s annual Keith L. and “Hospital staff monitors cardiac we tend to take roadway safety for Ware Journalism Competition and care.” granted. But what about bicycles? walked away with three first-place Reporter Jan Waddell won first It can get awfully dark on unlit sec- awards. place in the Contractor/Stringer tions of certain streets, so common Judging was held at our major com- photography category with “Kwaja- sense dictates that when biking mand, U.S. Army Space and Missile lein Remembers,“ “Medical mission during hours of darkness we should Defense Command in Huntsville , immunizes children on Ebadon,“ use a bike light. -

"Political Correctness in the Newsroom" by Robert Novak Syndicated Columnist, Host, "The Capital Gang"

"Political Correctness in the Newsroom" by Robert Novak Syndicated Columnist, Host, "The Capital Gang" A free press is one of the foundations of a obert Novak writes "Inside free soct'ety. Yet Americans increasingly dis RReport," one of the longest running syndicated columns in the trust and resent the media. A major reason nation. With his partner, Rowland is that many journalists have crossed the line Evans, he also edits a newsletter, from reporting to advocacy. They have, in the Evans-Novall Political Report, effect, adopted a new liberal creed· "all the and hosts CNN's news that's 'politically correct' to print. " interview program, "Evans and Novak." ow does one define "political correct Additionally, ness" in the newsroom? One need look Mr. Novak is a rov no further than the new style book of ing editor for Hthe Los Angeles Times, one of the Reader's Digest, a largest, most influential newspapers in the frequent cohost nation. It forbids reporters to write about a of "Crossfire," an "Dutch treat" because this phrase is allegedly interviewer on "Meet insulting to the Dutch. Nor can one report that the Press," and the a person "welshed on a bet" because that would coexecutive pro be insulting to the Welsh, and one certainly ducer and host cannot write about a segment of our population of CNN's weekend once known simply as "Indians." They must roundtable, "The always be referred to as "Native Americans." Capital Gang." He Jokingly, I asked one of the Los Angeles Times bas written Tbe editors, "How do you refer to Indian summer? Is Agony of tbe GOP: 1964 and it now Native American summer?" He replied cowritten Lyndon B. -

439 CNN America, Inc. and Team Video Services, LLC and National

CNN AMERICA, INC. 439 CNN America, Inc. and Team Video Services, LLC judge’s decision, we summarize his findings and indicate and National Association of Broadcast Employ- where our analysis differs.2 ees and Technicians, Communications Workers I. BACKGROUND; JOINT-EMPLOYER STATUS of America, Local 31, AFL–CIO A. Facts CNN America, Inc. and Team Video Services, LLC In 1980, Turner Communications created CNN as a and National Association of Broadcast Employ- 24-hour cable television news channel. Headquartered in ees and Technicians, Communications Workers Atlanta, Georgia, CNN is in the business of news gather- of America, Local 11, AFL–CIO. Cases 05–CA– ing, producing, and broadcasting. At the time of the 031828 and 05–CA–033125 hearing in this case, it maintained a network of bureaus September 15, 2014 and over 900 national and international affiliates. DECISION AND ORDER CNN opened its Washington, DC news bureau in 1980. It opened its New York City (NYC) news bureau BY CHAIRMAN PEARCE AND MEMBERS MISCIMARRA in 1985. From the start, CNN made the decision that the AND HIROZAWA operation of the electronic equipment at those bureaus This case concerns CNN’s unlawful replacement of a would be performed by outside contractors. Between unionized subcontractor, TVS, with an in-house nonun- 1980 and 2002, it awarded exclusive technical support ion work force at its Washington, DC, and New York service contracts, known as Electronic News Gathering City bureaus. The judge found that CNN and TVS were Service Agreements (ENGAs), to a series of companies. joint employers, and that CNN violated the Act by (1) The first company to operate the equipment at the DC terminating the subcontracts with TVS out of antiunion bureau was Mobile Video Services. -

How to Talk to a Liberal (If You Must)

How to Talk to a Liberal (If You Must) The World According to ANN COULTER How to Talk to a Liberal Historically, the best way to convert liberals is to have them move out of their parents' home, get a job, and start paying taxes. But if this doesn't work, you might have to actually argue with a liberal. This is not for the faint of heart. It is important to remember that when arguing with liberals, you are always within inches of the "Arab street." Liberals traffic in shouting and demagogy. In a public setting, they will work themselves into a dervish-like trance and start incanting inanities: "BUSH LIED, KIDS DIED!" "RACIST!" "FASCIST!" "FIRE RUMSFELD!" "HALLIBURTON!" Fortunately, the street performers usually punch themselves out eventually and are taken back to their parents' house. Also resembling the Arab street, liberals are chock-full of conspiracy theories. They invoke weird personal obsessions like a conversational deus ex machina to trump all facts. You think you're talking about the war in Iraq and suddenly you start getting a disquisition on Nixon, oil, the neoconservatives, Vietnam (Tom Hayden discusses gang violence in Los Angeles as it relates to Vietnam), or whether Bill O'Reilly's former show, Inside Edition, won the Peabody or the Peanuckle Award. This is because liberals, as opposed to sentient creatures, have a finite number of memorized talking points, which they periodically try to shoehorn into unrelated events, such as when Nancy Pelosi opposed the first Gulf war in 1991 on the grounds that it would cause environmental damage in Kuwait. -

140995 Hvd.Indd

HARVARD UNIVERSITY John F. MAY 2004 Kennedy New Poll Released School of INSTITUTE Government JFK Jr. Forum Dedicated Candidates Come to Harvard New Frontier Awards Created OF POLITICS Richard Neustadt Remembered Campaign ’04 Comes to Harvard Senator John Kerry takes questions during a taping of “Hardball” at the Forum Bush/Cheney ’04 Campaign Manager Ken Mehlman speaks at the Forum Welcome to the Institute of Politics at Harvard University Dan Glickman, Director As the 2004 election heats up, the Institute of Politics continues to be a national hub of political activity, discussion, and debate. • In September, we rededicated the Forum to recognize John F. Kennedy, Jr. We were honored to hear from Senator Edward Kennedy, Caroline Kennedy, and other dignitaries and IOP friends on this special occasion. • Students participated in the campaigns of all major presidential candidates. • We hosted eight of the leading Democratic Presidential contenders for live question-and-answer sessions hosted by MSNBC’s Chris Matthews. • Our Resident Fellows this semester are a diverse group – the former four- term Republican mayor of Knoxville, an executive at DreamWorks and an expert on the youth perspective on policy issues, the Vice President of Programs at the Reverend Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow/PUSH Coalition, a Democratic political strategist with 25 years’ experience teaching, writ- ing, and working in American politics, the Washington Bureau Chief of the Chicago Sun-Times, and the former Governor of Minnesota. Interest and participation in their study groups has been unprecedented. • Our most recent national poll on the political personality of America’s college students finds they are frustrated about the war and the job market and leaning in favor of Senator Kerry. -

24-Hour Cable News the Mainstreaming of Politicization

24-Hour Cable News The Mainstreaming of Politicization Christopher D. Stanley Boston College Copyright © May 2006 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ii Abstract 1 Introduction 2 Background 6 Research Question 23 Relevance 24 Literature Review 32 Methodology 41 Findings 45 Discussion 80 Conclusion 85 Reference List 89 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As with every accomplishment in my life, I can attribute all the merits of this paper to my Mother and Father. You both have literally taught me everything I’ve needed to know in life, and are my role models in more ways than you know. Because this paper is the culmination of an education that would not have been possible without your sacrifice and support, I dedicate this to you. From its inception, Dr. William Stanwood has been an invaluable source of wisdom, guidance and better judgment in transforming this concept from fantasy to reality over the last year and a half. You embody everything that a professor, thesis advisor, and friend should be. I would also like to thank the Communication department of Boston College as a collective whole; a better education I could not have asked for. To Jen, my fellow nerd and partner in crime – you never cease to amaze me with your thoughtfulness and caring. I consider myself the luckiest guy alive just for knowing you. And for Boston College – Till time shall be no more / And thy work is crown’d. / For Boston, for Boston / For Thee and Thine Alone. The Mainstreaming of Politicization 1 ABSTRACT Though the number of viewers flocking to the three major 24-hour cable news networks appears to be reaching a plateau, their influence on the American news-viewing public has revolutionized the industry. -

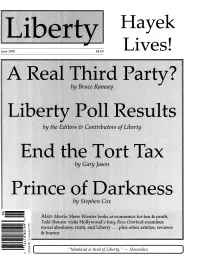

Liberty Magazine June 2008.Pdf Mime Type

Hayek June 2008 $4.00 Lives! "Mankind is tired ofLiberty. 1/ - Mussolini June 2008 Inside Liberty Volume 22, Number 5 4 Letters Scribble, scribble, scribble. 7 Reflections We craft the perfect bill, snort space monkey, melt our pennies, visit the stupidest state, fawn over Lincoln, give pregnant women the boot, dodge bullets with Hillary, learn to love Big Brother, smoke easy behind the fourth wall, and remember Charlton Heston. Features 19 A Real Party? Suddenly, everybody wants to run under the Libertarian Party banner. Bruce Ramsey watches the race. 23 The Ethics ofTort Reform Gary Jason shows how to remedy the excessive litigation that is costing us hundreds of billions of dollars a year. Twenty Years of Liberty 29 The Liberty Poll Since its founding, Liberty has been trying to keep track of libertarians - who they are and what they think. We now present the results of the latest Liberty Poll. 46 Moral Absolutes, Truth, and Liberty Ross Overbeek revisits the survey of libertarian attitudes that he helped to create 20 years ago. Reviews 51 Prince of Darkness or Angel of Light? For a change, as Stephen Cox discovers, a Washington insider's tell-all fulfills its promise. 55 Leave Us Alone! The Leave Us Alone Coalition: now there's a good name. Bruce Ramsey investigates the movement behind the moniker. 56 Economics for Fun & Profit Martin Morse Wooster reveals that economics is no longer the dismal science. 57 Hayek Lives The afterlife of Friedrich Hayek has been long and strong. Lanny Ebenstein investigates his posthumous influence. 59 Screwy Enough? Cary Grant, Rosalind Rusell, Thelma Ritter .. -

The Online News Association Convention

09np0043.qxp 9/15/09 11:03 AM Page 1 BBC WORLD NEWS AMERICA Congratulates this year’s News & Documentary Emmy® nominees and recognizes those being honored WEEKNIGHTS 7 & 10PM/ET 09np0043.pdf RunDate: 09/ 21 /09 Full Page Color: 4/C 09np0040.qxp 9/11/09 1:44 PM Page 1 CONGRATULATES OUR NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY® NOMINEES ORLA GUERIN – “CHAOS IN DR CONGO” Outstanding Coverage of a Breaking News Story in a Regularly Scheduled Newscast Best Story in a Regularly Scheduled Newscast RUPERT WINGFIELD-HAYES – “CHINESE OPENNESS” Outstanding Feature Story in a Regularly Scheduled Newscast WEEKNIGHTS 7 & 10PM/ET 09np0040.pdf RunDate: 09/ 21 /09 Full Page Color: 4/C NP_cover7.0.qxp:ContentWare 9/15/09 2:42 PM Page 1 September 2009 News on a Budget Results of cutbacks begin to show up on-air Page 4 Online Journalism Hyperlocal the new coverage trend on the Web Page 56 News & Doc Emmys COVERING TOWN HALLS TV crews wrestle to bring A custom guide back the real story to the program Page 10 follows Page 12 09np0005.qxp 7/17/09 12:48 PM Page 1 “ ” -- Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac This year’s tours: 1. Ultralight Delivery: Crane Conservation on Our Fractured Landscape Wake up with the birds to see one of North America’s SOCIETY OF ENVIRONMENTAL JOURNALISTS most endangered species. TH 2. Future Energy Choices 19 ANNUAL Join us as we head to Southeastern Wisconsin to talk carbon capture, big coal, solar, Great Lakes wind, and lithium ion batteries. CONFERENCE 3. Cruising Lake Michigan Hop aboard an EPA research vessel as we talk invasive species, bad ballast water, contaminated Hosted by the University of Wisconsin–Madison sediment and Great Lakes fi sh populations.