5.3 Three Body Scatter Signature Producing Uncertainties in Doppler Radial Velocity Structures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparison of Polarimetric Radar Signatures in Hailstorms Simultaneously Observed by C-Band and S-Band Radars

ERAD 2012 - THE SEVENTH EUROPEAN CONFERENCE ON RADAR IN METEOROLOGY AND HYDROLOGY Comparison of polarimetric radar signatures in hailstorms simultaneously observed by C-band and S-band radars. R. Kaltenboeck1 and A. Ryzhkov2 1Austrocontrol - Aviation Weather Service, Vienna and Institute of Meteorology and Geophysics, University of Innsbruck, Austria, [email protected] 2 Cooperative Institute for Mesoscale Meteorological Studies, Atmospheric Radar Research Center, University of Oklahoma and National Severe Storms Laboratory, NOAA, Norman, OK, USA, [email protected] (Dated: 16 May 2012) 1. Introduction Direct comparisons of polarimetric signatures in hailstorms simultaneously observed by C-band and S-band radars in Oklahoma reveal numerous differences. Vertical profiles of radar reflectivity ZH, differential reflectivity ZDR, and cross-correlation coefficient ρhv in the major downdraft cores of hailstorms at S and C bands reflect fundamental differences in backscattering by melting hailstones and large raindrops at the two wavelengths (e.g. Kaltenboeck and Ryzhkov 2012). The focus of this study is to examine the signatures at the periphery of the major reflectivity cores which are affected by strong size sorting (Kumjian and Ryzhkov 2009), three-body scattering (TBSS, Lemon 1998), attenuation (Borowska et al. 2011 ), updrafts (e.g., Straka et al. 2000), side lobe contamination, nonuniform beam filling and reflectivity gradients across the beam (Ryzhkov 2007), depolarization (Ryzhkov and Zrnić 2007), low signal to noise ratio (SNR), and range dependency which manifest themselves very differently at S and C bands. Some of these factors are closely associated with hail itself and its size and their comparative analysis may provide additional insight into the microphysics of hail generation and fallout. -

Hail Spike Impacts on Doppler Radial Velocity Data During Recent Convective Events in the Continental United States

Hail Spike Impacts on Doppler Radial Velocity Data During Recent Convective Events in the Continental United States CHRIS SMALLCOMB National Weather Service, Weather Forecast Office Reno, Nevada Corresponding Author Address: 2350 Raggio Parkway Reno, NV 89512 775.673.8100 x224 [email protected] (Submitted 7 April 2008; In final form 10 September 2008) ABSTRACT The tropospheric mid-level three body scatter spike (TBSS) Doppler radar signature is widely used by National Weather Service forecasters as an indication of severe hail. Research describes the radial velocity signature associated with the TBSS as generally weak inbound. However, during recent severe convective events in the continental United States, several examples of the TBSS exhibiting high inbound radial velocity signatures have been noted. The cases presented demonstrate the TBSS can contaminate velocity data, thereby making storm interrogation and the warning decision process more complicated. It is emphasized that forecasters need to be cautious in analyzing the placement of these features within the overall storm structure before making a warning decision, particularly when weighing whether to issue or upgrade to a tornado warning. 1. Introduction The mid-level three body scatter spike (TBSS) or flare echo Doppler radar signature is a 10- 30 km long region of artifact echo aligned radially downrange from a highly reflective (>63 dBZ) echo core (Fig. 1). Caused by non-Rayleigh radar microwave scattering or Mie scattering (Zrnić 1987), the TBSS is widely used by National Weather Service (NWS) forecasters as a sufficient (not necessary) indication of very large hail within a severe thunderstorm (Fig. 2). Established research (Zrnić 1987; Lemon 1998; Wilson and Reum 1988) describes the common radial velocity signature associated with the TBSS as weak inbound coupled with high spectrum width (SW) values. -

Radar Artifacts and Associated Signatures, Along with Impacts of Terrain on Data Quality

Radar Artifacts and Associated Signatures, Along with Impacts of Terrain on Data Quality 1.) Introduction: The WSR-88D (Weather Surveillance Radar designed and built in the 80s) is the most useful tool used by National Weather Service (NWS) Meteorologists to detect precipitation, calculate its motion, estimate its type (rain, snow, hail, etc) and forecast its position. Radar stands for “Radio, Detection, and Ranging”, was developed in the 1940’s and used during World War II, has gone through numerous enhancements and technological upgrades to help forecasters investigate storms with greater detail and precision. However, as our ability to detect areas of precipitation, including rotation within thunderstorms has vastly improved over the years, so has the radar’s ability to detect other significant meteorological and non meteorological artifacts. In this article we will identify these signatures, explain why and how they occur and provide examples from KTYX and KCXX of both meteorological and non meteorological data which WSR-88D detects. KTYX radar is located on the Tug Hill Plateau near Watertown, NY while, KCXX is located in Colchester, VT with both operated by the NWS in Burlington. Radar signatures to be shown include: bright banding, tornadic hook echo, low level lake boundary, hail spikes, sunset spikes, migrating birds, Route 7 traffic, wind farms, and beam blockage caused by terrain and the associated poor data sampling that occurs. 2.) How Radar Works: The WSR-88D operates by sending out directional pulses at several different elevation angles, which are microseconds long, and when the pulse intersects water droplets or other artifacts, a return signal is sent back to the radar. -

Three-Body Scatter Spike

RADAR OBSERVATIONS OF A RARE “TRIPLE” THREE-BODY SCATTER SPIKE Phillip G. Kurimski NOAA/National Weather Service Detroit/Pontiac, Michigan Weather Forecast Office Abstract afternoon and evening across northeast Wisconsin. The hail storms were responsible forOn 1over July 10.3 2006, million several dollars supercell of damage. thunderstorms The most produced intense storm significant produced hail during hail up the to late 4 in. in diameter that damaged over 100 cars and numerous homes in Oconto County, Wisconsin. This storm exhibited a rare, triple three-body scatter spike (TBSS) and a very long, impressive 51 mile TBSS. This paper will diagnose the structure and character of the paperhail cores will responsibleconnect the forunusually the multiple large TBSSscattering using angle several associated different with tools, the illustrating 51 mile longthat TBSSTBSS areto the 3-D increased features thatscattered are not energy confined responsible to a single for elevation the long TBSS.slice. In addition, Corresponding Author: Phillip G. Kurimski NOAA/ National Weather Service, 9200 White Lake Road, White Lake, Michigan 48386-1126 E-mail: [email protected] Kurimski 1. Introduction Since the early days of weather radar, radar operators three distinct TBSS signatures in a single volume scan andsignatures elevation has angle been is observed a phenomenon (Stan-Sion that haset al. yet 2007), to be result from large hail in a thunderstorm (Wilson and Reum documented and is the main motivation for this paper. The 1988).have noticed When athe “flare radar echo” beam down encounters the radial large believed hailstones to with a coating of liquid water, power from the radar is throughout this paper. -

Redalyc.Detection of Hail Through the Three-Body Scattering Signatures

Atmósfera ISSN: 0187-6236 [email protected] Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México México CARBUNARU, DANIEL VICTOR; SASU, MONICA; BURCEA, SORIN; BELL, AURORA Detection of hail through the three-body scattering signatures and its effects on radar algorithms observed in Romania Atmósfera, vol. 27, núm. 1, 2014, pp. 21-34 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Distrito Federal, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=56529644003 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Atmósfera 27(1), 21-34 (2014) Detection of hail through the three-body scattering signatures and its effects on radar algorithms observed in Romania DANIEL VICTOR CARBUNARU, MONICA SASU and SORIN BURCEA National Meteorological Administration, Bucharest, Romania Correponding author: D. V. Carbunaru; e-mail: [email protected] AURORA BELL Bureau of Meteorology, Melbourne, Australia Received October 10, 2012; accepted September 5, 2013 RESUMEN La red de radares de la Administración Meteorológica Nacional de Rumania (NMA, por sus siglas en inglés) integra cinco radares de la banda S y cuatro radares de la banda C. La observación de procesos de convección en Rumania mediante la red de radares Doppler ofrece una nueva perspectiva para comprender el riesgo climatológico de ciertas regiones y entornos de mesoescala. Se observan mejor los sistemas convectivos altamente organizados, como las supercélulas, y su amenaza subsiguiente puede predecirse mejor durante el pronóstico a muy corto plazo (nowcasting) utilizando campos de velocidad Doppler y algoritmos de detección como mesociclones (MESO) y firmas de vórtice de tornados (TVS, por sus siglas en inglés). -

Hailstorms (CH20) Hail Impacts

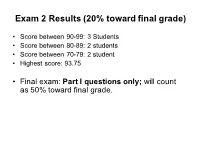

Exam 2 Results (20% toward final grade) • Score between 90-99: 3 Students • Score between 80-89: 2 students • Score between 70-79: 2 student • Highest score: 93.75 • Final exam: Part I questions only; will count as 50% toward final grade. MET 4300 Lecture 32 Hailstorms (CH20) Hail Impacts Window damage during the Forth Worth, Texas, March 28, 2001 (plywood replaced windows due to hail damage. Hail size upto 3 inches) Brush CO, 3 hours after a hailstorm Ø$900M per yr in property damage in the US Ø$140M per year in crop damage in US Ø2001, worst year, $2.5B property damage due to one hailstorm: the Tri-State hailstorm. ØHuman fatalities are rare: only 50 injuries per year in US; total 4 deaths per decade; Nepal 29 deaths in 1990, China 200 deaths in 1932, India 200 deaths in 1888. Sampled Distribution of Hailstone Sizes Potential for damage increases with size and fall speed: D=2cm hails will fall at Vt=20 m/s (45mph) in still air; D=5cm, Vt=46 m/s (103 mph) Largest hailstone: d=20.3 cm (8 inches) Most are about 1 cm diameter D>2.5 cm is relatively rare. > 5 mm to qualify as hail Smaller are graupel Under 8 hailshafts in storms in eastern CO Hailstone Size Descriptions by Meteorologists Pea sized --- 0.5 cm Marble sized---1 cm Golf ball sized---4 cm Tennis ball sized – 6cm Baseball sized---7 cm Grapefruit sized---10 cm Softball sized---12 cm A spiked hailstone compared to a $20 bill Quarter coin sized = 2.5 cm = 1 in Record Hailstones: diameter, weight, & circumference Current record holder (the white cast) for diameter & weight): Vivian Current record holder for South Dakota, 23JUL2010: 8 inches in diameter, 1.9375 lb, 18.62 inches circumference): in circumference. -

Detailed Flow, Hydrometeor and Lightning Characteristics of An

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 12, 6679–6698, 2012 www.atmos-chem-phys.net/12/6679/2012/ Atmospheric doi:10.5194/acp-12-6679-2012 Chemistry © Author(s) 2012. CC Attribution 3.0 License. and Physics Detailed flow, hydrometeor and lightning characteristics of an isolated thunderstorm during COPS K. Schmidt1, M. Hagen1, H. Holler¨ 1, E. Richard2, and H. Volkert1 1Deutsches Zentrum fur¨ Luft- und Raumfahrt (DLR), Institut fur¨ Physik der Atmosphare,¨ Oberpfaffenhofen, Germany 2Laboratoire d’Aerologie,´ CNRS and Universite´ de Toulouse III, Toulouse, France Correspondence to: K. Schmidt ([email protected]) Received: 2 March 2012 – Published in Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss.: 16 April 2012 Revised: 5 July 2012 – Accepted: 13 July 2012 – Published: 1 August 2012 Abstract. The three-hour life-cycle of the isolated thun- gence line eventually removed the convective inhibition and derstorm on 15 July 2007 during the Convective and set deep convection in motion. A shear line in the radial ve- Orographically-induced Precipitation Study (COPS) is docu- locity relative to the Feldberg radar site shows good agree- mented in detail, with a special emphasis on the rapid devel- ment beween observation and simulation, whereas the onset opment and mature phases. Remote sensing techniques as 5- location of deep convection exhibits a horizontal discrepancy min rapid scans from geostationary satellites, combined ve- of 15 km. A quantitative schematic of the isolated thunder- locity retrievals from up to four Doppler-radars, the polari- storm synthesizes all retrieved characteristics. metric determination of hydrometeors and spatio-temporal occurrences of lightning strokes are employed to arrive at a quantification of the physical parameters of this, during the COPS period, singular event. -

Environmental & Socio-Economic Studies

Environmental & Socio-economic Studies DOI: 10.2478/environ-2020-0016 Environ. Socio.-econ. Stud., 2020, 8, 3: 34-47 © 2020 Copyright by University of Silesia in Katowice ________________________________________________________________________________________________ Original article Radar reflectivity signatures and possible lead times of warnings for very large hail in Poland based on data from 2007-2015 Wojciech Pilorz 1, 2*, Ewa Łupikasza1 1Institute of Earth Sciences, Faculty of Natural Sciences, University of Silesia in Katowice, Będzińska Str. 60, 41-200 Sosnowiec, Poland 2Skywarn Poland Association, 29 Listopada Str. 18/19, 00-465 Warsaw, Poland E–mail address (*corresponding author): [email protected] ORCID iD: Wojciech Pilorz: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9204-0680; Ewa Łupikasza: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3910-9076 ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT Hail involving very large hailstones (maximum diameter ≥ 5 cm), is a rare but very hazardous phenomenon in Poland, and can be forecast using reflectivity signatures. Every year, Poland experiences from one to over a dozen storms with such large hailstones. Despite the current recommendations regarding polarimetric techniques used in hail risk monitoring, Poland does not have a fully polarimetric radar network. Therefore it is essential to check hail detection capabilities using only reflectivity techniques based on individual radar systems involving hail detection algorithms such as Waldvogel et al. (1979) or Vertically Integrated Liquid thresholds connected with manual signature analysis to get better warning decisions. This study is aimed to determine the reflectivity features, thresholds and lead times for nowcasting of severe storms with very large hailstones in Poland, using data from the Polish radar system and from the European Severe Weather Database for the period 2007‒2015. -

Radar Signatures That May Indicate Strong/Severe Storms

Technology and Storm Spotting Doppler Radar: The most effective tool to detect precipitation is radar. Radar, which stands for RAdio Detection And Ranging, has been utilized to detect precipitation, and especially thunderstorms, since the 1940's. Radar enhancements have enabled NWS forecasters to examine storms with more precision. The radars used by the National Weather Service utilize Doppler weather radar principles. All weather radars, including Doppler, electronically convert reflected radio waves into pictures showing the location and intensity of precipitation. However, Doppler radars can also measure the frequency change in returning radio waves which allows Meteorologists to display motions toward or away from the radar. This ability to detect motion has greatly improved the meteorologist's ability to peer inside thunderstorms and determine if there is rotation in the cloud, often a precursor to the development of tornadoes. Doppler Velocity Wind Data showing a tornadic circulation near Van wert, Ohio on November 10th 2002. Doppler Weather Radar Images Satellite Imagery: Reflectivity is the amount of transmitted power returned to the radar receiver after hitting precipitation. It is measured in National Weather Service satellites are capable of producing information on decibels (dBZ). Composite Reflectivity utilizes all radar clouds and moisture in three primary forms (Visible, Infrared (IR) and Water elevation scans to create an image and displays the maximum Vapor) reflectivity vertically at any point. Precipitation images (One Hour and Storm Total) are created by applying computer Visible imagery is an image of the earth in visible light. This is a similar algorithms to reflectivity imagery to estimate rainfall. manner to that of a person taking a picture with a camera. -

Hailstorms Rakes Portions of West Central Florida May 3Rd and 4Th

Hailstorms Rakes Portions of West Central Florida May 3rd and 4th Animation of Composite Reflectivity, 252 PM to 415 PM EDT, May 3 2005. Note the "storm cell mitosis"! Events Occur in 18 hour Period May 3rd and 4th A northward moving front, an upper level jet streak, and an As with all supercells, this storm was rotating increasingly unstable atmosphere contributed to the at multiple layers, and a distinct hail spike development of severe thunderstorms during the afternoon was noted. The rotation continued for more and evening of May 3rd, and again during the morning of than 30 minutes, despite a weakening trend. May 4th. The unusual late season event, more typical in Toward 4 PM, though reflectivity had Oklahoma than in Florida in May, produced at least one decreased, the storm nearly exhibited a bona-fide supercell thunderstorm (rotating through many Bounded Weak Echo Region. It was at this layers) on the 3rd. As of this writing, the predominant event time that the hail core was rapidly was large hail - up to baseball size in diameter! descending, and moments later the golfball to baseball size hail was reported near Fort Meteorology/May 3 Ogden (western Desoto County). In Florida, the typical Midwestern/Great Plains precursors needed for widespread severe weather are rarely seen. Soon after, the supercell began to collapse. However, similar, smaller scale versions can develop. Such But the event had just begun. The once- was the case on May 3rd and 4th. The 8 AM EDT May 3rd weakening left moving storm re-intensified as Ruskin sounding showed the potential, namely in the very it moved into Hardee County. -

Radar Measurements

CHAPTER CONTENTS Page CHAPTER 7. RADAR MEASUREMENTS ............................................... 680 7.1 General ................................................................... 680 7.1.1 The weather radar ................................................... 680 7.1.2 Radar characteristics, terms and units .................................. 681 7.1.3 Radar accuracy requirements ......................................... 681 7.2 Radar principles ............................................................ 682 7.2.1 Pulse radars ........................................................ 682 7.2.2 Propagation radar signals. 686 7.2.3 Attenuation in the atmosphere ........................................ 687 7.2.4 Scattering by clouds and precipitation .................................. 688 7.2.5 Scattering in clear air. 689 7.3 The radar equation for precipitation targets .................................... 689 7.4 Basic weather radar system and data .......................................... 691 7.4.1 Reflectivity ......................................................... 691 7.4.2 Doppler velocity .................................................... 692 7.4.3 Dual polarization .................................................... 694 7.5 Signal and data processing .................................................. 696 7.5.1 The Doppler spectrum ............................................... 696 7.5.2 Power parameter estimation .......................................... 696 7.5.3 Ground clutter and point targets ..................................... -

Notes and Correspondence

500 WEATHER AND FORECASTING VOLUME 16 NOTES AND CORRESPONDENCE Observations of a Severe Left Moving Thunderstorm LEWIS D. GRASSO AND ERIC R. HILGENDORF Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere, Fort Collins, Colorado 10 October 2000 and 2 March 2001 ABSTRACT Observations have shown that right moving thunderstorms are favored in environments characterized by clockwise-turning hodographs. There are, however, a few observational and numerical studies of long-lived, left moving storms within environments characterized by clockwise-turning hodographs. For example, a documented left mover that occurred on 26 May 1992, near Coldspring, Texas, with a mesoanticyclone and hail spike (also called a three-body scattering signature) produced severe weather. Although a few cases have been documented, left moving thunderstorms have received less study than right moving cells. The long-lived, severe thunderstorm of 17 May 1996 is presented to improve documentation of left moving thunderstorms. The storm occurred over eastern Nebraska and will be referred to as the York County storm. This left mover resulted from storm splitting and moved to the west of a surface cold front. The relatively isolated storm subsequently split approximately 1 h later, yielding a new right moving thunderstorm. Doppler radial velocities suggested the existence of a mesoanticyclone within the York County storm. Hail, 1.75 in. in diameter, was produced by the storm around the time the updraft split. There were many similarities between the York County storm and the 26 May 1992 Coldspring left moving severe thunderstorm. Both storms were relatively isolated, contained mesoanticyclones, and produced severe weather after the vertically integrated liquid water obtained a maximum value.