Report of the Inquest Into the Deaths Arising from the Thredbo Landslide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November 18–20, 2016 Lake Crackenback Resort & Spa Trextriathlon.Com.Au Welcome from the NSW Government

#GetDirtyDownUnder #TreXTri presented by November 18–20, 2016 Lake Crackenback Resort & Spa trextriathlon.com.au Welcome from the NSW Government On behalf of the NSW Government I’d like to invite you to Lake Crackenback Resort & Spa in New South Wales, Australia, for the 2016 ITU World Cross Triathlon Championships, to be held in November next year. The NSW Government is proud to have secured the World Cross Triathlon Championships for the Snowy Mountains, through our tourism and major events agency Destination NSW in partnership with In2Adventure and Triathlon Australia. The Snowy Mountains is an ideal host for the World Championships, and I am sure that visiting competitors will be enthralled by the region’s breathtaking beauty. The Snowy Mountains has everything you would want from an adventure sports location, from stunning mountain bike trails to pristine lakes, with plenty of space to compete, train or just explore. I encourage all visitors to the Snowy Mountains to take some time to experience everything the region has to offer, with top class restaurants, hotels and attractions as well as the inspiring landscapes. New South Wales also has much more to offer competitors and visitors, from our global city, Sydney, to our spectacular coastline and wide variety of natural landscapes. I wish all competitors the best of luck in Sardinia and we look forward to welcoming you all to New South Wales for the 2016 ITU World Cross Triathlon Championships. Stuart Ayres Minister for Trade, Tourism and Major Events Minister for Sport 1 Sydney is a city on the move, with exciting new harbourside precincts featuring world-class hotels and sleek shopping districts. -

Ace Works Layout

South East Australian Transport Strategy Inc. SEATS A Strategic Transport Network for South East Australia SEATS’ holistic approach supports economic development FTRUANNSDPOINRTG – JTOHBSE – FLIUFETSUTYRLE E 2013 SEATS South East Australian Transport Strategy Inc. Figure 1. The SEATS region (shaded green) Courtesy Meyrick and Associates Written by Ralf Kastan of Kastan Consulting for South East Australian Transport Strategy Inc (SEATS), with assistance from SEATS members (see list of members p.52). Edited by Laurelle Pacey Design and Layout by Artplan Graphics Published May 2013 by SEATS, PO Box 2106, MALUA BAY NSW 2536. www.seats.org.au For more information, please contact SEATS Executive Officer Chris Vardon OAM Phone: (02) 4471 1398 Mobile: 0413 088 797 Email: [email protected] Copyright © 2013 SEATS - South East Australian Transport Strategy Inc. 2 A Strategic Transport Network for South East Australia Contents MAP of SEATS region ......................................................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary and proposed infrastructure ............................................................................ 4 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 6 2. Network objectives ............................................................................................................................... 7 3. SEATS STRATEGIC NETWORK ............................................................................................................ -

Snowy Mountains Region Visitors Guide

Snowy Mountains Region Visitors Guide snowymountains.com.au welcome to our year-round The Snowy Mountains is the ultimate adventure four-season holiday destination. There is something very special We welcome you to come and see about the Snowy Mountains. for yourself. It will be an escape that you will never forget! playground It’s one of Australia’s only true year- round destinations. You can enjoy Scan for more things to do the magical winter months, when in the Snowy Mountains or visit snowymountains.com.au/ a snow experience can be thrilling, things-to-do adventurous and relaxing all at Contents the same time. Or see this diverse Kosciuszko National Park ............. 4 region come alive during the Australian Folklore ........................ 5 spring, summer and autumn Snowy Hydro ............................... 6 months with all its wonderful Lakes & Waterways ...................... 7 activities and attractions. Take a Ride & Throw a Line .......... 8 The Snowy Mountains is a natural Our Communities & Bombala ....... 9 wonder of vast peaks, pristine lakes and rushing rivers and streams full of Cooma & Surrounds .................. 10 life and adventure, weaving through Jindabyne & Surrounds .............. 11 unique and interesting landscapes. Tumbarumba & Surrounds ......... 12 Take your time and tour around Tumut & Surrounds .................... 13 our iconic region enjoying fine Our Alpine Resorts ..................... 14 food, wine, local produce and Go For a Drive ............................ 16 much more. Regional Map ............................. 17 Regional Events & Canberra ...... 18 “The Snowy Mountains Getting Here............................... 19 – there’s more to it Call Click Connect Visit .............. 20 than you think!” 2 | snowymountains.com.au snowymountains.com.au | 3 Australian folklore Horse riding is a ‘must do’, when and friends. -

Capital Coast and Country Touring Route Canberra–Tablelands–Southern Highlands– Snowy Mountains–South Coast

CAPITAL COAST AND COUNTRY TOURING ROUTE CANBERRA–TABLELANDS–SOUTHERN HIGHLANDS– SNOWY MOUNTAINS–SOUTH COAST VISITCANBERRA CAPITAL COAST AND COUNTRY TOURING 1 CAPITAL, COAST AND COUNTRY TOURING ROUTE LEGEND Taste the Tablelands SYDNEY Experience the Southern Highlands SYDNEY AIRPORT Explore Australia’s Highest Peak Enjoy Beautiful Coastlines Discover Sapphire Waters and Canberra’s Nature Coast Royal Southern Highlands National Park Young PRINCES HWY (M1) Mittagong Wollongong LACHLAN Boorowa VALLEY WAY (B81) Bowral ILL AWARR Harden A HWY Shellharbour Fitzroy Robertson HUME HWY (M31) Falls Kiama Goulburn Kangaroo Yass Gerringong Valley HUME HWY (M31) Jugiong Morton Collector National Nowra Shoalhaven Heads Murrumbateman FEDERAL HWY (M23) Park Seven Mile Beach BARTON HWY (A25) Gundaroo National Park Gundagai Lake Jervis Bay SNOWY MOUNTAINS HWY (B72) Hall George National Park Brindabella National Bungendore Sanctuary Point Park Canberra KINGS HWY (B52) Jervis Bay International Morton Conjola Sussex CANBERRA Airport National National Inlet Park Park TASMAN SEA Tumut Queanbeyan Lake Conjola Tidbinbilla Budawang Braidwood National Mollymook Park Ulladulla PRINCES HWY (A1) Namadgi (B23) HWY MONARO Murramarang Yarrangobilly National Park National Park Batemans Bay AUSTRALIA Yarrangobilly Mogo Caves Bredbo CANBERRA SYDNEY PRINCES HWYMoruya (A1) MELBOURNE Bodalla Tuross Head Snowy Mountains Cooma SNOWY MOUNTAINS HWY (B72) Narooma KOSCIUZSKO RD Eurobadalla Montague Perisher National Park Tilba Island Jindabyne Thredbo Wadbilliga Bermagui Alpine National -

A Century of Storms, Fire, Flood and Drought in New South Wales, Bureau Of

The Australian Bureau of Meteorology celebrated its centenary as a Commonwealth Government Agency in 2008. It was established by the Meteorology Act 1906 and commenced operation as a national organisation on 1 January 1908 through the consoli- dation of the separate Colonial/State Meteorological Services. The Bureau is an integrated scientific monitoring, research and service organisation responsible for observing, understanding and predicting the behaviour of Australia’s weather and climate and for providing a wide range of meteorological, hydrological and oceanographic information, forecasting and warning services. The century-long history of the Bureau and of Australian meteorology is the history of the nation – from the Federation Drought to the great floods of 1955, the Black Friday and Ash Wednesday bushfires, the 1974 devastation of Darwin by cyclone Tracy and Australia’s costliest natural disaster, the Sydney hailstorm of April 1999. It is a story of round-the-clock data collection by tens of thousands of dedicated volunteers in far-flung observing sites, of the acclaimed weather support of the RAAF Meteorological Service for southwest Pacific operations through World War II and of the vital role of the post-war civilian Bureau in the remarkable safety record of Australian civil aviation. And it is a story of outstanding scientific and technological innovation and international leadership in one of the most inherently international of all fields of science and human endeavour. Although headquartered in Melbourne, the Bureau has epitomised the successful working of the Commonwealth with a strong operational presence in every State capital and a strong sense of identity with both its State and its national functions and responsibilities. -

Kangaroo Island, NSW South Coast, Alpine Region & Victorian East

FIRES UPDATE Kangaroo Island, NSW South Coast, Alpine Region & Victorian East Gippsland 06 January 2020 Dear All, Please find below the latest update on the bushfire crisis currently occurring in certain parts of Australia. Goway has been proactively contacting and have successfully relocated all clients whose travel plans will be impacted by these fires. Kangaroo Island Fire On the evening of Friday 3rd January, a fire situation escalated rapidly and without warning on Kangaroo Island, which has resulted in the loss of key tourism infrastructure on the western side of the Island, including Southern Ocean Lodge, and Hanson Bay Wildlife Sanctuary & Cabins. The eastern side of the island has been unaffected by the fire. Firefighters on the island have been battling fires since before Christmas, but extreme temperatures and wind caused the blaze to go dangerously out of control resulting in the destruction of much of the Flinders Chase National Park. Goway is pleased to say that as of Friday evening, there were no Goway booked clients on the island. Summary: Sealink have confirmed that all day tours are cancelled for today 6th January and likely Tuesday 7th. Further updates will be provided as to the status moving forward. We are proactively re-booking affected clients that are due to stay over the coming days and taking advise from our supplier partners. For clients with accommodation in the ‘current’ safe areas, it may be ok to travel later in the week. These areas include, Penneshaw, Kingscote, American River & Willougby. Please see the image below for the location of the properties that are presently unaffected. -

Great Drives in New South Wales

GREAT DRIVES IN NSW Enjoy the sheer pleasure of the journey on inspirational drives in NSW. Visitors will discover views, wildlife, national parks full of natural wonders, beaches that are the envy of world and quiet country towns with stories to tell. Essential lifestyle ingredients such as wineries, great regional dining and fantastic places to spend the night cap it all off. Take your time and discover a State that is full of adventures. Discover more road trip inspiration with the Destination NSW trip and itinerary planner at: www.visitnsw.com/roadtrips The Legendary Pacific Coast Fast facts A scenic coastal drive north from Sydney to Brisbane Alternatively, fly to Newcastle, Ballina Byron or the Gold Coast and hire a car Drive length: 940km. Toowoon Bay, Central Coast Why drive it? This scenic drive takes you through some of the most striking landscapes in NSW, an almost continuous line of surf beaches, national parks and a hinterland of rolling green hills and friendly villages. The Legendary Pacific Coast has many possible themed itineraries: Coastal and Aquatic Trail Culture, Arts and Heritage Trail Food and Wine and Farmers’ Gate Journey Legendary Kids Trail National Parks and State Forests Nature Trail Legendary Surfing Safari Backpacker and Working Holiday Trail Whale-watching Trail. What can visitors do along the way? On the Central Coast, drop into a wildlife or reptile park to meet Newcastle Ocean Baths, Newcastle Australia’s native animals Stop off at Hunter Valley for cellar door wine tastings and award-winning -

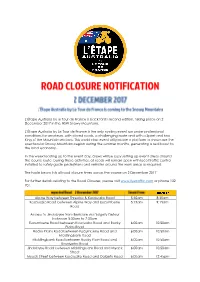

L'etape-ROAD CLOSURE NOTIFICATION

L’Étape Australia by le Tour de France is back for its second edition, taking place on 2 December 2017 in the NSW Snowy Mountains. L’Étape Australia by Le Tour de France is the only cycling event run under professional conditions for amateurs, with closed roads, a challenging route and with a Sprint and two King of the Mountain sections. This world class event will provide a platform to showcase the spectacular Snowy Mountains region during the summer months, generating a real boost to the local economy. In the week leading up to the event day, crews will be busy setting up event areas around the course route. During these activities, all roads will remain open with local traffic control installed to safely guide pedestrians and vehicles around the work areas as required. The table below lists all road closure times across the course on 2 December 2017. For further details relating to the Road Closures, please visit www.livetraffic.com or phone 132 701. Alpine Way between Thredbo & Kosciuszko Road 5:30am 8:30am Kosciuszko Road between Alpine Way and Eucumbene 5:15am 9:15am Road Access to Jindabyne from Berridale via Dalgety Detour between 5:00am to 7:00am Eucumbene Road between Kosciuszko Road and Rocky 6:00am 10:50am Plains Road Rocky Plains Road between Eucumbene Road and 6:00am 10:50am Middlingbank Road Middlingbank Road between Rocky Plain Road and 6:00am 10:50am Kosciuszko Road Jindabyne Road between Middlingbank Road and Myack 6:00am 10:50am Street Myack Street between Kosciuszko Road and Dalgety Road 6:00am 12:45pm Dalgety Road between Myack Street and The Snowy River 7:15am 12:15pm Way Campbell Street through Dalgety 7:15am 12:15pm The Snowy River Way between Dalgety and Barry Way 7:15am 2:00pm Barry Way between The Snowy River Way and Kosciuszko 7:30am 2:00pm Road Kosciuszko Road between Alpine Way and Perisher 8:30am 4:30pm NOTE: Emergency Services will be available to access properties impacted by the event closures at all times in case of an emergency. -

Kyg6id1twsjdcsev.Pdf

NOTICE OF EVENT 2016 THREDBO ANC SBX RACES MONDAY 15TH AUGUST – WEDNESDAY 17TH AUGUST MONDAY 15 AUGUST Training Day TUESDAY 16 AUGUST FIS ANC SBX Qualification and Race 1 WEDNESDAY 17 AUGUST FIS ANC SBX Qualification and Race 2 THURSDAY 18 AUGUST Weather Day LOCATION Thredbo, NSW, Australia HOSTED BY Thredbo Alpine Village and Ski & Snowboard Australia (SSA) ELIGIBILITY Conditions of entry as per FIS rules and quotas together with any special rules as announced by Ski & Snowboard Australia. Competitions are open to all FIS affiliated associations and current FIS registered athletes. Australian entrants must be a member of Ski & Snowboard Australia. ENTRIES Entries can be submitted online via the SSA website (www.skiandsnowboard.org.au). Entries close at 1.00pm on Monday 8th August. Entry fee is $85 per race. Late entries may be accepted at the Organizing Committees discretion and will be subject to a $85 late fee. INTERNATIONAL ENTRIES All international entries are to be submitted by the competitors National Federation on a standard FIS Entry Form. Competitors are also required to register and pay online via the online event entry system, www.skiandsnowboard.org.au. Ski & Snowboard Australia ENTRIES TO BE SUBMITTED TO: Level 2, 105 Pearl River Road Docklands, Victoria [email protected] FIRST TEAM CAPTAINS MEETING AND DRAW 6.00pm Sunday 14th August at Townsend Room, Thredbo Alpine Hotel. Prior to first day of training. 6.00pm Monday 15th August at Townsend Room, Thredbo Alpine Hotel. Draw, update of Program & Bib distribution etc. ALL COMPETITORS MUST BE REPRESENTED AT THE TEAM CAPTAINS MEETING 2 Notice of Event ‐ 2016 Thredbo ANC SBX Races LIFT TICKETS Discounted competitors’ tickets are available for $A69/day for training and race days. -

Kosciuszko National Park Closed Areas Date: 16 February 2020 at 10:55 To: [email protected]

From: Brindabella Ski Club [email protected] Subject: Kosciuszko National Park Closed Areas Date: 16 February 2020 at 10:55 To: [email protected] Sections of Kosciuszko National Park have been reopened, but areas which have been burnt or have ongoing fire suppression operations remain closed. Areas Recently Opened: • All areas south of Mt Jagungal and east of the following roads / trails are open to the public: Khancoban – Cabramurra Rd, Alpine Way and Cascade Trail (refer to map). This includes all backcountry areas which have not been impacted by fire. Overnight camping is permitted in these areas. This includes: o Kosciuszko Road - Jindabyne to Charlotte Pass o Guthega Road - Kosciuszko Road to Guthega Village o Charlotte Pass, Perisher Valley, Smiggin Holes, Guthega, Diggers Creek, Wilsons Valley, Sawpit Creek, Waste Point – visitors need to check whether resort facilities and hospitality venues are open for business o Alpine Way between Jindabyne and Thredbo Village o Thredbo Village and Thredbo resort lease area o Ngarigo, Thredbo Diggings and Island Bend campgrounds - for day use and overnight camping o Snowy Mountains Highway – visitors must stay within the road corridor and be aware of hazards such as damaged buildings and burnt trees o Blowering campgrounds - Log Bridge, The Pines, Humes Crossing and Yachting Point o All walks on the Main Range, including to Mt Kosciuszko and surrounding the alpine resort areas o Barry Way – open to the Victorian border. Lower Snowy picnic and campgrounds are open and include; Jacobs River, Halfway Flat, No Name, Pinch River, Jacks Lookout and Running Waters o Schlink Pass trail and associated huts (Horse Camp Hut, White River Hut, Schlink Hut, Valentine Hut) o Mt Jagungal. -

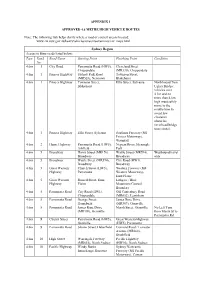

APPENDIX 1 APPROVED 4.6 METRE HIGH VEHICLE ROUTES Note: The

APPENDIX 1 APPROVED 4.6 METRE HIGH VEHICLE ROUTES Note: The following link helps clarify where a road or council area is located: www.rta.nsw.gov.au/heavyvehicles/oversizeovermass/rav_maps.html Sydney Region Access to State roads listed below: Type Road Road Name Starting Point Finishing Point Condition No 4.6m 1 City Road Parramatta Road (HW5), Cleveland Street Chippendale (MR330), Chippendale 4.6m 1 Princes Highway Sydney Park Road Townson Street, (MR528), Newtown Blakehurst 4.6m 1 Princes Highway Townson Street, Ellis Street, Sylvania Northbound Tom Blakehurst Ugly's Bridge: vehicles over 4.3m and no more than 4.6m high must safely move to the middle lane to avoid low clearance obstacles (overhead bridge truss struts). 4.6m 1 Princes Highway Ellis Street, Sylvania Southern Freeway (M1 Princes Motorway), Waterfall 4.6m 2 Hume Highway Parramatta Road (HW5), Nepean River, Menangle Ashfield Park 4.6m 5 Broadway Harris Street (MR170), Wattle Street (MR594), Westbound travel Broadway Broadway only 4.6m 5 Broadway Wattle Street (MR594), City Road (HW1), Broadway Broadway 4.6m 5 Great Western Church Street (HW5), Western Freeway (M4 Highway Parramatta Western Motorway), Emu Plains 4.6m 5 Great Western Russell Street, Emu Lithgow / Blue Highway Plains Mountains Council Boundary 4.6m 5 Parramatta Road City Road (HW1), Old Canterbury Road Chippendale (MR652), Lewisham 4.6m 5 Parramatta Road George Street, James Ruse Drive Homebush (MR309), Granville 4.6m 5 Parramatta Road James Ruse Drive Marsh Street, Granville No Left Turn (MR309), Granville -

NSW Snowy Mountains Road and Vehicle Regulations for Winter 2019

Be prepared. Check weather forecasts NSW Snowy Mountains Road and Vehicle Regulations and road for Winter 2019 conditions: While Kosciuszko’s mountain roads take you to many spectacular places you do need to take a few precautions and be aware that weather and road conditions can change dramatically in Updates and a short space of time. Information can be __________________________________________________________________________ obtained from: ALPINE WAY (beyond Thredbo): Chains must be carried in all two-wheel drive vehicles during the winter season between Thredbo and Tom Groggin. It is recommended but not compulsory that vehicles carry chains between Jindabyne and Thredbo Cooma Visitors Centre KOSCIUSZKO ROAD 119 Sharp St Cooma TO PERISHER: Chains must be carried in all two-wheel drive vehicles on the Kosciuszko Ph: 02 6455 1742 Road from the park boundary. www.visitcooma.com.au KOSCIUSZKO RD PERISHER RMS Ph: 132 701 TO CHARLOTTE PASS: This road will be closed to vehicle access once it becomes impassable due to snow. Access to Charlotte Pass Village is by over snow transport only. LOCAL RADIO STATIONS: GUTHEGA ROAD: Chains must be carried in all two wheel drive vehicles during the winter season. Cooma SNOWY MTNS HWY: It is recommended but not compulsory that vehicles carry chains between 2XL (918AM) or Cooma and Tumut during the winter season. Snow FM (97.7) KIANDRA TO CABRAMURRA/ Southern Kosciuszko MT SELWYN LINK ROAD: It is recommended but not compulsory that vehicles carry chains during 2XL (96.3AM) the winter season. Snow FM (94.7) CABRAMURRA TO ABC Bega (95.5FM) KHANCOBAN ROAD: This road is closed from the NSW June long weekend to the NSW October long weekend.