Circassian Cuisine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Potato - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Potato - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Log in / create account Article Talk Read View source View history Our updated Terms of Use will become effective on May 25, 2012. Find out more. Main page Potato Contents From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Featured content Current events "Irish potato" redirects here. For the confectionery, see Irish potato candy. Random article For other uses, see Potato (disambiguation). Donate to Wikipedia The potato is a starchy, tuberous crop from the perennial Solanum tuberosum Interaction of the Solanaceae family (also known as the nightshades). The word potato may Potato Help refer to the plant itself as well as the edible tuber. In the region of the Andes, About Wikipedia there are some other closely related cultivated potato species. Potatoes were Community portal first introduced outside the Andes region four centuries ago, and have become Recent changes an integral part of much of the world's cuisine. It is the world's fourth-largest Contact Wikipedia food crop, following rice, wheat and maize.[1] Long-term storage of potatoes Toolbox requires specialised care in cold warehouses.[2] Print/export Wild potato species occur throughout the Americas, from the United States to [3] Uruguay. The potato was originally believed to have been domesticated Potato cultivars appear in a huge variety of [4] Languages independently in multiple locations, but later genetic testing of the wide variety colors, shapes, and sizes Afrikaans of cultivars and wild species proved a single origin for potatoes in the area -

Banquet 1 Banquet 2 Brunch Cocktails

Our menu is designed to be shared as per the Middle Eastern tradition. We suggest choosing four dishes to share between 2 guests. SOURDOUGH MANOUSHE COOKED TO ORDER IN THE WOOD OVEN BANQUET 1 45pp Basturma, confit onions, pine nuts and goat’s curd 20 Choice of manoush cooked to order in the wood oven Spiced sujuk and stretched curds 19 Eggplant fatteh, chickpeas, nuts, burnt butter Labnah and zaatar 16 Baalbek fried eggs, lamb awarma, tahini yoghurt, smoked almond crumb, flatbread Freshly shucked Tasmanian Pacific oyster, rose mignonette 5ea Beetroot, sheep's curd, pomegranate dressing, flatbread 21 Pressed watermelon, pistachio cream, berries, mastic booza Sumac cured ocean trout,, pickled cucumber, cacik 22 BANQUET 2 69pp Bekaa chicken wings, harissa emulsion, rose 18 petals Bekaa chicken wings, harissa emulsion, rose petals Duck bits shawarma sandwich, potato bread, pickled cabbage 16 Falafel crumpet, tahini, pickled onion, soft boiled egg, parsley Falafel crumpet, tahini, pickled onion, soft boiled egg, 14 parsley Eggplant fatteh, chickpeas, nuts, burnt butter Green ful medames, avocado, soft poached 20 GrilledMBNCSVNQ GSFFLBI & currant salata LFCBOFTFPMJWF egg, malawach Fattoush, tomatoes, summer purslane, watermelon radish, Smoked eggplant & prawn menemen, 24 pomegranates tomato, breakfast peppers, saj Pressed watermelon, pistachio cream, berries, mastic booza Baalbek fried eggs, lamb awarma, tahini yoghurt, 25 smoked almond crumb Eggplant fatteh, chickpeas, nuts, burnt butter 25 THE BOTTOMLESS 90 minutes with a set menu Grilled -

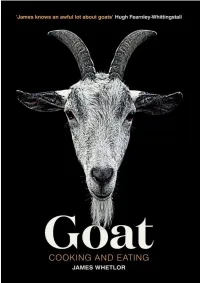

Goat’S Place in History

Publishing Director and Editor: Sarah Lavelle Designer: Will Webb Recipe Development and Food Styling: Matt Williamson Photographer: Mike Lusmore Additional Food Styling: Stephanie Boote Copy Editing: Sally Somers Production Controller: Nikolaus Ginelli Production Director: Vincent Smith First published in 2018 by Quadrille, an imprint of Hardie Grant Publishing Quadrille 52–54 Southwark Street London SE1 1UN quadrille.com Text James Whetlor 2018 Photography Mike Lusmore 2018 Image 1 University of Manchester 2018 Image 2 Farm Africa / Nichole Sobecki 2018 Design and layout Quadrille Publishing Limited 2018 eISBN: 978 1 78713 279 5 Contents Title Page Foreword by Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall Introduction Ötzi the Iceman The goat’s place in history Goats and modern farming Goats on the menu Leather Farm Africa Recipes Slow Quick Cooks Over Fire Roast Baked Basics Acknowledgements Index Recipe index Foreword There’s often a great deal to be sorry about in the world of modern food production. Indeed, there are so many serious problems, worrying issues and shameful practices that it’s easy to feel overwhelmed. But there are also innovations, solutions and great ideas – things to be celebrated and enjoyed that offer a fantastic counterpoint to the bad news. These bright, good ideas offer the way forward and it’s imperative that we throw a spotlight on them – which is why I’m delighted to be introducing this, James’s book. I first knew James as a talented chef in the River Cottage kitchen. He’s now also proved himself a writer and a successful ethical businessman. Cabrito, James’s company, was born after he took an uncompromising look at a tough problem within our food system – the wholesale slaughter of the male offspring of dairy goats soon after birth. -

Dessert Wine Pairings

SHARED DINING MENU’S Dishes selected by our chef Shared dining menu’s start from 2 persons and are the best to order per table In case you prefer a specific dish from our menu you can always let us know Dessert (Our menu’s are also available in completely vegan and vegetarian) Knafeh | vermicelli of filodough 9,50 Dates in red port, mint sauce 8,50 FENICIE MAZZA CHEF MAZZA with a filling of cheese Authentic Lebanese (Combination of fis hand meat) Halawet el jibn |cheesedough with cream 8,50 Baklawa |filling of dates and walnut 7, 50 2 salads 2 salads with a sauce of mint 5 cold mazza’s 5 cold mazza’s 3 warm mazza’s 3 warm mazza’s Kids ice cream 4,50 Booza | Syrian homemade rolled icecream 8,50 1 warm fish mazza choice of chocolate, vanilla , mango 27,50 p.p 32,50 p.p FENICIE MENU CHEF MENU Authentic Lebanese (Combination of fish and meat ) 2 salads 2 salads 5 cold mazza’s 5 cold mazza’s 3 warm mazza’s 4 warm mazza’s Maincourse Main course (choice of fish, meat or vegetarian) (on charcoal grilled steak) dessert dessert 37,50,- p.p 42,50 p.p SHARED DINING Combination of fish, meat and vegetarian Lebanese Specials 65,- p.p Wine Pairings Oumsiyat Heritage Oumsiyat Passion • Oumsiyat Blanc de blancs • Oumsiyat SauvignonBlanc/Chardonnay • Oumsiyat Rosé Soupir • Oumsiyat Cabernet Sauvignon/Merlot • Oumsiyat Rouge desir • Oumsiyat Syrah • Oumsiyat Dessert wine • Oumsiyat Dessert wine 16,- P.P. 19,- P.P. Soup Warm mazza’s Charcoal Grill 250 gr. -

BANQUET 1 45Pp BANQUET 2 69Pp BRUNCH COCKTAILS

Our menu is designed to be shared as per the Middle Eastern tradition. We suggest choosing four dishes to share between 2 guests. SOURDOUGH MANOUSHE COOKED TO ORDER BANQUET 1 45pp IN THE WOOD OVEN Basturma, confit onions, tomato, pine nuts and goat’s curd 19 Manoushe cooked to order in the wood oven served with pickles House sujuk and stretched curds 19 Eggplant fatteh, warm yoghurt, crisp bread, nuts, burnt butter Labnah and zaatar 15 Baalbek fried eggs, lamb awarma, tahini yoghurt, smoked almond crumb, flatbread Handmade shanklish, charred dill cucumbers, flatbread 17 Pressed watermelon and barberry, pistachio friand, berries, ginger biscuit, set cream Bekaa chicken wings, harissa emulsion, rose petals 18 BANQUET 2 69pp Al-muhuffin, house merguez sausage, fried egg, 17 batata harra hash brown, toum Bekaa chicken wings, harissa emulsion, rose petals Falafel crumpet, tahini, pickled onion, soft boiled egg, parsley 14 Falafel crumpet, tahini, pickled onion, soft boiled egg, parsley Spanner crab menemen, Turkish scrambled eggs with 28 Eggplant fatteh, warm yoghurt, crisp bread, nuts, burnt butter tomato, breakfast peppers, burnt butter, saj Wood roasted spatchcock, fenugreek, kishk, grilled peppers Baalbek fried eggs, lamb awarma, tahini yoghurt, smoked 25 Batata harra, fried potatoes, toum, coriander, green chilli zhoug almond crumb, flatbread Red velvet lettuce, buttermilk rose dressing, celery, za’atar, radish, Hot smoked salmon, whipped roe, walnuts, Aleppo 28 fried pita Eggplant fatteh, warm yoghurt, crisp bread, nuts, burnt butter -

Arco Iris 2020.Pdf

w w w w. t h e m a n o h a r. c o m The Manohar, situated at the centre of city, ideally located for shopping and experiencing all that the city has to offer. The hotel with a superb choice of luxurious accomodation, that exudes glamour with a contemporary edge. Within our purpose-built conference facilities, we have a choicew of well-appointed function rooms that can be easily adapted to suit any occasion from a large corporate event to a small private party. Besides the luxury rooms and suites, The Manohar hotel has plenty more facilities to offer including the best of world cuisines under one roof, Bars, Swimming Pool & Health Club. O L D A I R P O R T E X I T R OA D, B E G U M P E T, 6 6 5 4 3 4 5 6 | 9 1 9 24 6 2 2 8 3 4 9 H Y D E RA B A D, T E L A N GA N A - 5 0 0 0 1 6 01 At IHM Shri shakti, let it be academics or activities we always believe in positive College Song change and improvement. Excellence just happens as Future is bright and sure, routine. Keeping the track it was like this never before record intact, this year’s annual College corridors and halls, magazine published with greater ambience which enthralls. enhancement. This 26th edition of “Arco Iris” comes We keep our hands on our hearts with online content. It is my pleasure to present this special souvenir book from my desk. -

2014-Campbell-Culinary-Trendscape

Insights for Innovation and Inspiration from Thomas W. Griffiths, CMC Vice President, Campbell’s Culinary & Baking Institute (CCBI) Tracking the ebb and flow of North American food trends can be a daunting task, even for a seasoned culinary professional, which is why we take a team approach to monitoring food trends. We begin with our most valued resource—culinary intuition. We draw first on the expertise of our global team of chefs and bakers and the inspiration that they find in culinary tours, literature and many other sources including our trusted industry partners. This year we have taken our collective ideas and compiled our first-ever CCBI Culinary TrendScape report, which highlights what we see as the trends to watch—the foods that excite our palettes and our imagination. Some of these trends may inspire future Campbell products, while some may not. Either way, we think it’s important to stay on the pulse of what people are eating and how their tastes are evolving as a result of global influences. 2014 HOT TOPICS This 2014 Culinary TrendScape report offers our unique point of view on what we’ve These themes are identified as the ten most dynamic food trends to watch, from Brazilian Cuisine to the driving force behind Bolder Burgers. We also look at overarching themes—hot topics—that have risen this year’s top trends to the top in the marketplace. Authenticity • A Balanced Some themes, like authenticity and interest in a balanced lifestyle, have been hot Lifestyle • Distinctive Flavors • topics the past few years and remain influential in this year’s TrendScape. -

TRADITIONAL HIGH ANDEAN CUISINE ORGANISATIONS and RESCUING THEIR Communities

is cookbook is a collection of recipes shared by residents of High Andean regions of Peru STRENGTHENING HIGH ANDEAN INDIGENOUS and Ecuador that embody the varied diet and rich culinary traditions of their indigenous TRADITIONAL HIGH ANDEAN CUISINE ORGANISATIONS AND RESCUING THEIR communities. Readers will discover local approaches to preparing some of the unique TRADITIONAL PRODUCTS plants that the peoples of the region have cultivated over millennia, many of which have found international notoriety in recent decades including grains such as quinoa and amaranth, tubers like oca (New Zealand yam), olluco (earth gems), and yacon (Peruvian ground apple), and fruits such as aguaymanto (cape gooseberry). e book is the product of a broader effort to assist people of the region in reclaiming their agricultural and dietary traditions, and achieving both food security and viable household incomes. ose endeavors include the recovery of a wide variety of unique plant varieties and traditional farming techniques developed during many centuries in response to the unique environmental conditions of the high Andean plateau. TRADITIONAL Strengthening Indigenous Organizations and Support for the Recovery of Traditional Products in High-Andean zones of Peru and Ecuador HIGH ANDEAN Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations Regional Office for Latin America and the Caribbean CUISINE Av. Dag Hammarskjöld 3241, Vitacura, Santiago de Chile Telephone: (56-2) 29232100 - Fax: (56-2) 29232101 http://www.rlc.fao.org/es/proyectos/forsandino/ FORSANDINO STRENGTHENING HIGH ANDEAN INDIGENOUS ORGANISATIONS AND RESCUING THEIR TRADITIONAL PRODUCTS Llaqta Kallpanchaq Runa Kawsay P e r u E c u a d o r TRADITIONAL HIGH ANDEAN CUISINE Allin Mikuy / Sumak Mikuy Published by Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Regional Office for Latin America and the Caribbean (FAO/RLC) FAO Regional Project GCP/RLA/163/NZE 1 Worldwide distribution of English edition Traditional High Andean Cuisine: Allin Mikuy / Sumak Mikuy FAORLC: 2013 222p.; 21x21 cm. -

Download the Celiac "Traffic Light" Meal Plan

Celiac Disease Program “The Celiac Traffic Light Guide” Now that you’ve mastered the gluten-free diet, it’s time to get to shopping! At first, navigating the grocery store can feel daunting. Fortunately you have this tool to help guide you in selecting foods that are gluten-free. With time, you’ll naturally learn to categorize foods in your mind to make shopping an easier and enjoyable experience! GO! SLOW! STOP! These foods are gluten-free These foods may be safe These foods are not gluten- and are safe to eat every to eat, but be careful because free and should be avoided! day. You should choose they can’t be guaranteed Eating them may cause foods from this list. to be gluten-free! you to experience mild to severe reactions due to gluten contamination. CHIPS CEREAL CEREAL S P CEREAL Breads, Cereals, Flours, and Other Grains GO! SLOW! STOP! • Amaranth • Buckwheat flour • Barley • Arrowroot (sometimes is mixed • Bran with wheat flour), pasta, • Buckwheat • Bulgur and breads • Cornmeal • Cereals • Flavored rice mixes • Corn tortillas • Couscous • Flavored snacks • Cream of rice • Crackers (chips, popcorn, etc.) • Flax • Croutons • Oats • Gluten-free cereals • Durum • Oatmeal • Hominy (grits) • Einkorn • Potato bread • Millet • Emmer • Rice and corn cereals • Montina (may contain barley) • Farina • Nut flours (almond, Farro hazelnut, pecan) • Flour tortillas • Plain corn chips • Freekeh • Plain popcorn • Graham • Plain rice cakes • Granola • Plain tortilla chips • Hydrolyzed • Potato flour vegetable protein • Potato starch • Hydrolyzed -

Lunch Specials: 11:30 A.M—3:00 P.M

Ambadi Kebab and Grill Real Indian food Dine in +take out Catering + delivery. ORDER ONLINE @ .AMBADI.USA.COM 141 east post road White plains, ny 10601 p.914-686-2014 & 914-686-1746. Fax=914-831-5420 LUNCH SPECIAL:- TUEsDAY- SUNDAY 11:30AM-3:00PM DINNER: - 5:00PM-10:00PM DELIVERY AVAILABLE BY: UBER eats www.ambadi-usa.com LUNCH SPECIALS: 11:30 A.M—3:00 P.M. ONLY 1. VEGETABLE SAMOSA =$5.95 2. KEEMA SAMOSA =$6.95 3. SEEK KEBAB LUNCH BOX = $9.95 4. SHRIMP LUNCH BOX =$13.95 5. CHICKEN MALAI KEBAB BOX = $9.95 6. MEAT PLATTER LUNCH BOX =$13.95 7. SALAD BOX = $6.95 8. VEGETARIAN BOX =$8.95 10. NON-VEGETARIAN BOX =$9.95 11. CHICKEN CURRY LUNCH BOX =$10.95 12. CHICKEN TIKKA MASALA LUNCH BOX =$10.95 13. BEEF CURRY LUNCH BOX =$11.95 14. SAG PANEER LUNCH BOX=$9.95 15. NAVARATAN KORMA LUNCH BOX= $9.95 16. CHOLE PESHWARI LUNCH BOX = $9.95 17. LAMB CURRY BOX=$12.95 18. CHAPPLI KEBAB BOX=$9.95 APPETIZERS and VEGETARIAN STARTERS: 1. SAMOSA = Triangular tasty pastry filled with potatoes, green peas, and spices.=$ 5.95 2. Mixed pakoras = Battered cauliflower, potatoes, and broccoli fritters with a sweet tamarind sauce=$7.95 3. Onion pakoras = A fritter made of onion, chickpea flour and spices=$ 5.95 4. Masala corn = Corn flavored with a blend of Indian spices and cilantro=$ 5.95 5. Samosa chat = Crushed samosa with yogurt, chickpeas, onions, tomatoes & tamarind sauce=$ 7.95 6. Bombay chat = Crispy flour tortillas garnished with chickpeas, yogurt, cilantro, spicy & sweet sauce=$ 7.95 7. -

Zhengzhou Azeus Machinery Co.,Ltd

Zhengzhou Azeus Machinery Co.,Ltd Address:A503 Suo Ke Yu Fa Building ,Jingliu Road,Zhengzhou City,China Mobile:0086-18203633056 Skype:luckstar0506 Email:[email protected] Samosa Making Machine Automatic samosa making machine can be used for dumpling(empanada), samosa, wonton, spring rolls,and ravioli by changing mold and head. Zhengzhou Azeus Machinery Co.,Ltd Address:A503 Suo Ke Yu Fa Building ,Jingliu Road,Zhengzhou City,China Mobile:0086-18203633056 Skype:luckstar0506 Email:[email protected] Working Principles: Put fillings and dough are put into hoppers, open filling switch and start machine. Then fillings is come into filling tube through filling pump and fillings screw. And at the same time,strip dough is formed into cylindric dough wrapper,hollow, through dough screw and dough mouth parts(it can form cylindric.Then dough wrapper with fillings are passed shaping moulds and pressed dumping. By changing moulds, it can make samosa,ravioli,dumpling,spring roll and woton. Dough and fillings note: 1.Dough: (1).Proportion of flour and water:1:0.38-0.4. (2).Usual dough mixer, it takes about 20 minutes,and 6minutes for Vacuum dough mixer.(Capacity 8kg dough mixer can satisfy your requirements.) (3).When dough is done,dough need to rest for about 5 minutes. (4).Please note that you need to warm water to mix flour in Winter, and usually cold water is OK. (5).Dough must be divided to strip dough, and then put into dough hopper. 2.Fillings: (1)Medium and high-grade samosa(dumpling), the content of meat is generally above 30%,vegetable particles is under 6mm (At most,6mm-10mm) for length. -

Beach House Menu

SALADS AND APPETIZERS MOCKTAILS ORANGE, BEETROOT AND BLUE CHEESE SALAD Ψ 95 ZOMBIE 75 crushed coriander seeds and lemon dressing grenadine, lemon, sprite HARISA SPICE PRAWNS 245 TROPICAL 85 lemon quinoa tabbouleh mango, strawberry, banana CAESAR SALAD WITH TIGER PRAWNS 245 PINEAPPLE CRUSH 75 iceberg lettuce, anchovy dressing, garlic croutons pineapple, orange, grenadine HONEY DEW MELON AND AIR DRIED BEEF 149 MILKSHAKE 90 rocket leaves, lemon dressing, local feta, hazelnuts vanilla, chocolate, strawberry CARPACCIO OF AUSTRALIAN BEEF TENDERLOIN 190 FRESH JUICES 57 extra virgin olive oil, rucola, parmesan, semidried tomato strawberry, lemon, mango, banana, sweet melon SMOKED SALMON 225 horseradish cream, capers, melba toast SOFT DRINKS 41 coke, diet coke, sprite, fanta SOUP WATER still small 22 large 32 CREAM OF MUSHROOM Ψ 90 sparkling (240ml) 35 fresh cream, truffle oil imported sparkling (240ml) 70 EGG DROP CHICKEN NOODLE SOUP 90 mushroom, coriander HOT BEVERAGES Tea 41 CREAM OF SEAFOOD 120 green, english breakfast, earl grey saffron, dill tomato COFFEE PASTA AND RISOTTO espresso, ristretto, macchiato 41 cappuccino, latte, double espresso 51 GREEN PEA AND MINT RISOTTO Ψ 175 sundried tomato, mascarpone cheese TURKISH COFFEE 59 SPAGHETTI LOBSTER AGLIO OLIO PEPPERONCINO 275 HOT CHOCOLATE 50 garlic, chili, extra virgin olive oil SEAFOOD RISOTTO Ψ 185 basil, tomato, saffron chef special vegetarian Ψ spicy Prices are in Egyptian Pounds including the service charge and other applicable taxes Prices are in Egyptian Pounds including the service