THE BEGINNINGS of the WINE INDUSTRY in the HUNTER VALLEY By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Draft HAFS Cumulative Index 1991

HUNGERFORD AND ASSOCIATED FAMILIES SOCIETY INC JOURNALS AND NEWSLETTERS INDEX to HAFS JOURNALS Vols 1 (May 1991) to 15, No 4 (Nov 2020) and HAFS NEWSLETTERS Nos 1 to 60 (1991 to August 2020) Compiled by Lesley Jane Abrahams (nee Hungerford) [H.4a.1b.1c.1d/E.6.5a.1b.1c.1d] and Hungerford and Associated Families Society Inc © Hungerford & Associated Families Society Inc 2021 Do not download or reproduce in any format without the express permission of the HAFS Committee. Legend: The references in this Cumulative Index have been organised alphabetically. Some entries might appear under several topics. References are indicated in this way: For the Journal (to end of 2010): J 5/1 = HAFS Journal, Volume 5 Number 1, followed by date and page numbers, eg J 5/1 May 1999 pp.19-22 From 2011 to 2019, References are indicated in this way: J 11-1 = HAFS Journal, Vol. 11, Number 1, followed by month, year and page numbers. This is consistent with the footers on each page of the journals for this time period. For Newsletter: N = Newsletter, followed by number, month year, and page numbers, eg N 17 Feb 1999 pp. 8-9; N 41 Feb 2011 pp. 8-9 Hungerfords Down Under code is given in parentheses, from 2nd ed, 2013. Where possible, codes from HDU, 1st ed 2001, and from Hungerfords of the Hunter, have been updated to match HDU, 2nd ed 2013. Stray Hungerfords have been realigned in HDU, 2nd ed 2013, consequently some codes in this index may not match the codes used in the articles as published in early issues. -

Kooragang Wetlands: Retrospective of an Integrated Ecological Restoration Project in the Hunter River Estuary

KOORAGANG WETLANDS: RETROSPECTIVE OF AN INTEGRATED ECOLOGICAL RESTORATION PROJECT IN THE HUNTER RIVER ESTUARY P Svoboda Hunter Local Land Services, Paterson NSW Introduction: At first glance, the Hunter River estuary near Newcastle NSW is a land of contradictions. It is home to one of the world’s largest coal ports and a large industrial complex as well as being the location of a large internationally significant wetland. The remarkable natural productivity of the Hunter estuary at the time of European settlement is well documented. Also well documented are the degradation and loss of fisheries and other wildlife habitat in the estuary due to over 200 years of draining, filling, dredging and clearing (Williams et al., 2000). However, in spite of extensive modification, natural systems of the estuary retained enough value and function for large areas to be transformed by restoration activities that aimed to show industry and environmental conservation could work together to their mutual benefit. By establishing partnerships and taking a collaborative and adaptive approach, the project was able to implement restoration and related activities on a landscape basis, working across land ownership and management boundaries (Kooragang Wetland Rehabilitation Project, 2010). The Kooragang Wetland Rehabilitation Project (KWRP) was launched in 1993 to help compensate for the loss of fisheries and other wildlife habitat at suitable sites in the Hunter estuary. This paper revisits the expectations and planning for the project as presented in a paper to the INTECOL’s V international wetlands conference in 1996 (Svoboda and Copeland, 1998), reviews the project’s activities, describes outcomes and summarises issues faced and lessons learnt during 24 years of implementing a large, long-term, integrated, adaptive and community-assisted ecological restoration project. -

The Sydney College

The Sydney College 1 3 -18 0 17 August 1992 Key to Abbreviations BC Born Colony F Father CF Came Free PCF Parents Came Free FCF Father Came Free MCF Mother Came Free GS Government Servant FGS Father Government Servant MGS Mother Government Servant TKS The King's School References: ADB Australian Dictionary ofBiography Mw Pioneer Families of Australia (5th ed), by P.C. Mowle G and S, A Biographical Register 1788-1939 (2 volumes), by Gibbney and Smith Religion: E ChUrch of England P Presbyterian W Wesleyan C Congregationalist RC Roman Catholic B Baptist J Jewish * in front of the accession number indicates the boy was also at The King's School * in front of a name indicates sponsored by that person. Explanatory Guide Through the kindness of Mrs lly Benedek, Archivist of Sydney Grammar School, a photostat of the roll of the Sydney College 1835-1850 was supplied to the Archivist of The King's School and has been placed on computer at The King's School Parramatta. The Sydney College Roll sets out bare details of enrolments: viz 1 Allen George 19/1/1835-3/1841 11 George Allen Toxteth Park George Allen 2 Bell Joshua 19/1/1835-8/1836 8 Thomas Bell Carters Bar. Removed to Parramatta Thomas Barker Subsequent research at The King's School involving the use of the New South Wales Births, Deaths and Marriages 1788-1856 has allowed some recording of exact dates of birth, exact dates of parents' marriage and on a few entries the candidate's marriage. The maiden names of many mothers have also been located. -

Hunter Valley: Coal Seam Gas Exclusion Zones Submission 8 November 2013

Director Assessment Policy, Systems & Stakeholder Engagement Department of Planning and Infrastructure Hunter Valley: Coal Seam Gas Exclusion Zones Submission 8 November 2013 Coal Seam Gas Exclusion Zones Submission: Hunter Valley This page was intentionally left blank 2 Coal Seam Gas Exclusion Zones Submission: Hunter Valley Foreword Closing the loop on CSG Mining in the Hunter Valley When it comes to coal seam gas (CSG) mining, protecting Australia’s most visited wine tourism region in its entirety - not in parts - is of paramount importance. And the time to do it is now. The NSW State Government should be recognised for delivering on its pre-election promises to preserve the Hunter Valley wine tourism region from CSG mining by confirming exclusion zones around the villages of Broke and Bulga as well as around significant areas defined as Viticulture Critical Industry Clusters (VCIC). But protecting most of the region, while leaving several critical areas open for CSG exploration and mining, could have devastating consequences for the iconic Hunter region as a whole – and undo the Government’s efforts thus far. While mining is obviously a legitimate land use and an important revenue source, this can’t justify allowing mining activities in areas where other existing, profitable industries would be adversely affected. Put simply, winemaking, tourism and CSG mining are not compatible land uses. The popularity and reputation of the Hunter Valley wine tourism region is fundamentally connected to the area’s natural beauty and landscape – and that natural beauty will fast disappear if the countryside is peppered with unsightly gas wells. Research reveals 80%1 of Hunter Valley visitors don’t want to see gas wells in the wine and tourism region, with 70%2 saying if gas wells are established they’ll just stop coming. -

A Growth Agenda for the Hunter Drivers of Population Growth

A growth agenda for the Hunter Drivers of population growth A report prepared for the Hunter Joint Organisation of Councils Dr Kim Johnstone, Associate Director Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Greater Newcastle and the Hunter region ........................................................................................... 2 Drivers of population change ........................................................................................................... 3 Population growth ............................................................................................................................ 3 Age profile ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Drivers of growth .............................................................................................................................. 6 Understanding migration.................................................................................................................. 8 Internal migration ............................................................................................................................. 8 Overseas migration ....................................................................................................................... -

Lower Hunter Regional Conservation Plan Cover Photos (Main Image, Clockwise): Hunter Estuaries (DECC Estuaries Unit) Mother and Baby Flying Foxes (V

Lower Hunter Regional Conservation Plan Cover photos (main image, clockwise): Hunter estuaries (DECC Estuaries Unit) Mother and baby flying foxes (V. Jones, DECC) Lower Hunter estuary, Hunter Wetlands National Park (G. Woods, DECC) Sugarloaf Range (M. van Ewijk, DECC) Published by: Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water NSW 59 Goulburn Street PO Box A290 Sydney South 1232 Phone: (02) 9995 5000 (switchboard) Phone: 131 555 (environment information and publications requests) Phone: 1300 361 967 (national parks information and publications requests) Fax: (02) 9995 5999 TTY: (02) 9211 4723 Email: [email protected] Website: www.environment.nsw.gov.au © Copyright State of NSW and Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water NSW. The Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water and State of NSW are pleased to allow this material to be reproduced for educational or non-commercial purposes in whole or in part, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. Specifi c permission is required for the reproduction of photographs and images. The material provided in the Lower Hunter Regional Conservation Plan is for information purposes only. It is not intended to be a substitute for legal advice in relation to any matter, whether particular or general. This document should be cited as: DECCW 2009, Lower Hunter Regional Conservation Plan, Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water NSW, Sydney. ISBN 978 1 74232 515 6 DECCW 2009/812 First published April 2009; Revised December 2009 Addendum In the Gwandalan Summerland Point Action Group Inc v. Minister for Planning (2009) NSWLEC 140 (Catherine Hill Bay decision), Justice Lloyd held that the decisions made by the Minister for Planning to approve a concept plan and project application, submitted by a developer who had entered into a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) and Deed of Agreement with the Minister for Planning and the Minister for Climate Change and the Environment were invalid. -

A History in Three Rivers

A History in Three Rivers Dungog Shire Heritage Study Thematic History April 2012 Michael Williams Gresford Crossing source: Dungog Shire Heritage Study, Karskens, 1986 Ships at Clarence Town source: Dungog Shire Heritage Study Karskens, 1986 Mill on the Allyn River source: Dungog Shire Heritage Study, Karskens, 1986 carste STUDIO Pty Ltd Architects and Heritage Consultants ADDENDUM TO THEMATIC HISTORY 1 DUNGOG HISTORICAL SOCIETY INC COMMENTS ON ‘A HISTORY IN THREE RIVERS’ JANUARY 2014 The Dungog Historical Society makes the following observations for your consideration. They are intended to enhance the project. One of the general observations is ‘A History in Three Rivers’ is largely about wealthier or prominent males their roles and their activities. Professor Glenda Strachan has carried out detailed research on Dungog highlighting the role of women and children in poorer farming families. Because of the nature of the research it also gives insights into life for poorer rural men. See, for example ‘Women’s Work is Never Done” The intersection of Work and Family’ 2004http://www.griffith.edu.au/?a=314657 accessed 10 January 2014, G Strachan, E Jordan, H Carey, ‘Women’s Work in a Rural Community: Dungog and the Upper Williams Valley 1880- 1900’ Labour History No 78, 28 May 2000, p 7 and G Strachan ‘Assumed but Rarely Documented: Women’s Entrepreneurial Activities in Late Ninetieth Country Australia’ www.historycooperative.org/proceedings/asslh/strachan accessed 13/9/2006 p7 Second paragraph reference to Barton – the point of the visit was electioneering for his seat of Hunter, which included Dungog. The first elections were held later in the year and he was elected unopposed. -

Hunter Valley NSW WINE REGIONS Hunter Valley

NSW WINE REGIONS Hunter Valley NSW WINE REGIONS Hunter Valley The Hunter Valley is Australia’s oldest GETTING THERE wine-growing region, dating back to the early 1820s. Today, this well-established HUNTER region just two hours north of Sydney offers VALLEY MUDGEE more than 150 wineries and cellar doors, ORANGE acclaimed restaurants, stunning scenery SYDNEY SOUTHERN and an endless amount of experiences. HIGHLANDS SHOALHAVEN Visitors to the Hunter Valley can enjoy unique experiences at award- CANBERRA COAST DISTRICT winning cellar doors, dining at some of Australia’s best restaurants, hot air balloon rides, horse riding and hiking in national parks. The BY CAR Hunter Valley also has a calendar packed with lively events and Approx. 2hrs from Sydney to Pokolbin Approx. 1hr from Newcastle to Pokolbin music festivals. Accommodation options range from luxury resorts NEAREST AIRPORT with golf courses and spas to boutique accommodation, nature Newcastle retreats and farm stays. BY TRAIN Approx. 2hrs 45min from Sydney to Maitland Meet Hunter Valley local heroes and learn more about Hunter Valley in this destination video. visitnsw.com Winery Experiences The district is home to some of Australia’s most distinctive and outstanding wines, most notably Hunter Valley semillon, and is also famous for producing outstanding shiraz, verdelho and chardonnay. AUDREY WILKINSON This 150-year-old vineyard, perched on the foothills of the Brokenback Range, has stunning 360-degree views of the surrounding countryside. Audrey Wilkinson is a family-run cellar door that offers tastings, picnics among the vines, behind-the-scenes tours and fortified wine and cheese pairings. There is also a free museum and guest accommodation in modern cottages. -

Goulburn River National Park and Munghorn Gap Nature Reserve

1 GOULBURN RIVER NATIONAL PARK AND MUNGHORN GAP NATURE RESERVE PLAN OF MANAGEMENT NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service February 2003 2 This plan of management was adopted the Minister for the Environment on 6th February 2003. Acknowledgments: This plan was prepared by staff of the Mudgee Area of the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service. The assistance of the steering committee for the preparation of the plan of management, particularly Ms Bev Smiles, is gratefully acknowledged. In addition the contributions of the Upper Hunter District Advisory Committee, the Blue Mountains Region Advisory Committee, and those people who made submissions on the draft plan of management are also gratefully acknowledged. Cover photograph of the Goulburn River by Michael Sharp. Crown Copyright 2003: Use permitted with appropriate acknowledgment. 3 ISBN 0 7313 6947 5 4 FOREWORD Goulburn River National Park, conserving approximately 70 161 hectares of dissected sandstone country, and the neighbouring Munghorn Gap Nature Reserve with its 5 935 hectares of sandstone pagoda formation country, both protect landscapes, biology and cultural sites of great value to New South Wales. The national park and nature reserve are located in a transition zone of plants from the south-east, north-west and western parts of the State. The Great Dividing Range is at its lowest elevation in this region and this has resulted in the extension of many plants species characteristic of further west in NSW into the area. In addition a variety of plant species endemic to the Sydney Sandstone reach their northern and western limits in the park and reserve. -

Hunter Investment Prospectus 2016 the Hunter Region, Nsw Invest in Australia’S Largest Regional Economy

HUNTER INVESTMENT PROSPECTUS 2016 THE HUNTER REGION, NSW INVEST IN AUSTRALIA’S LARGEST REGIONAL ECONOMY Australia’s largest Regional economy - $38.5 billion Connected internationally - airport, seaport, national motorways,rail Skilled and flexible workforce Enviable lifestyle Contact: RDA Hunter Suite 3, 24 Beaumont Street, Hamilton NSW 2303 Phone: +61 2 4940 8355 Email: [email protected] Website: www.rdahunter.org.au AN INITIATIVE OF FEDERAL AND STATE GOVERNMENT WELCOMES CONTENTS Federal and State Government Welcomes 4 FEDERAL GOVERNMENT Australia’s future depends on the strength of our regions and their ability to Introducing the Hunter progress as centres of productivity and innovation, and as vibrant places to live. 7 History and strengths The Hunter Region has great natural endowments, and a community that has shown great skill and adaptability in overcoming challenges, and in reinventing and Economic Strength and Diversification diversifying its economy. RDA Hunter has made a great contribution to these efforts, and 12 the 2016 Hunter Investment Prospectus continues this fine work. The workforce, major industries and services The prospectus sets out a clear blueprint of the Hunter’s future direction as a place to invest, do business, and to live. Infrastructure and Development 42 Major projects, transport, port, airports, utilities, industrial areas and commercial develpoment I commend RDA Hunter for a further excellent contribution to the progress of its region. Education & Training 70 The Hon Warren Truss MP Covering the extensive services available in the Hunter Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Infrastructure and Regional Development Innovation and Creativity 74 How the Hunter is growing it’s reputation as a centre of innovation and creativity Living in the Hunter 79 STATE GOVERNMENT Community and lifestyle in the Hunter The Hunter is the biggest contributor to the NSW economy outside of Sydney and a jewel in NSW’s rich Business Organisations regional crown. -

The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021

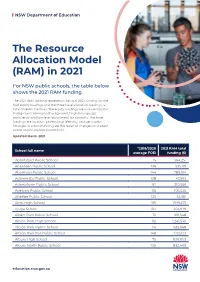

NSW Department of Education The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021 For NSW public schools, the table below shows the 2021 RAM funding. The 2021 RAM funding represents the total 2021 funding for the four equity loadings and the three base allocation loadings, a total of seven loadings. The equity loadings are socio-economic background, Aboriginal background, English language proficiency and low-level adjustment for disability. The base loadings are location, professional learning, and per capita. Changes in school funding are the result of changes to student needs and/or student enrolments. Updated March 2021 *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Abbotsford Public School 15 364,251 Aberdeen Public School 136 535,119 Abermain Public School 144 786,614 Adaminaby Public School 108 47,993 Adamstown Public School 62 310,566 Adelong Public School 116 106,526 Afterlee Public School 125 32,361 Airds High School 169 1,919,475 Ajuga School 164 203,979 Albert Park Public School 111 251,548 Albion Park High School 112 1,241,530 Albion Park Public School 114 626,668 Albion Park Rail Public School 148 1,125,123 Albury High School 75 930,003 Albury North Public School 159 832,460 education.nsw.gov.au NSW Department of Education *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Albury Public School 55 519,998 Albury West Public School 156 527,585 Aldavilla Public School 117 681,035 Alexandria Park Community School 58 1,030,224 Alfords Point Public School 57 252,497 Allambie Heights Public School 15 -

Australian Agricultural Company IS

INDEX Abbreviations A. A. Co.: Australian Agricultural Company I. S.: Indentured Servant Note: References are to letter numbers not page numbers. A. A. Co.: Annual Accounts of, 936; Annual James Murdoch, 797, 968; Hugh Noble, Report of, 1010; and letter of attorney 779; G. A. Oliver, 822; A. P. Onslow, empowering Lieutenant Colonel Henry 782; George T. Palmer, 789, 874; John Dumaresq to act as Commissioner of, Paul, 848; John Piper, senior, 799, 974; 1107; Quarterly Accounts of, 936; value of James Raymond, 995; separate, for supply property of at 3 April 1833, 980; see also of coal to Colonial Department and to stock in A. A. Co. Commissariat Department, 669, 725, 727; A. A. Co. Governor, London, see Smith, John: Benjamin Singleton, 889; William Smyth, A. A. Co. Stud, 706a, 898, 940d 759; Samuel Terry, 780; Thomas Walker, Aborigines: allegations of outrages against by 784, 811; William Wetherman, 917; T. B. Sir Edward Parry and others in employ of Wilson, 967; Sir John Wylde, 787, 976 A. A. Co., 989, 1011a, 1013; alleged offer ‘Act for preventing the extension of the of reward for heads of, 989; engagement of infectious disease commonly called the as guide for John Armstrong during survey, Scab in Sheep or Lambs’ (3 William IV No. 1025; and murder of James Henderson, 5, 1832) see Scab Act 906; number of, within limits of A. A. Co. Adamant: convicts on, 996, 1073 ‘s original grant, 715; threat from at Port advertisements; see under The Australian; Stephens, 956 Sydney Gazette; Sydney Herald; Sydney accidents, 764a Monitor accommodation: for A.