A Tale of Two Authors: the Shorter Fiction of Gaskell and Collins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contextualizing Value: Market Stories in Mid-Victorian Periodicals By

Contextualizing Value: Market Stories in Mid-Victorian Periodicals By Emily Catherine Simmons A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of English University of Toronto © Copyright Emily Catherine Simmons 2011 Abstract Contextualizing Value: Market Stories in Mid-Victorian Periodicals Emily Catherine Simmons Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of English, University of Toronto Copyright 2011 This dissertation examines the modes, means, and merit of the literary production of short stories in the London periodical market between 1850 and 1870. Shorter forms were often derided by contemporary critics, dismissed on the assumption that quantity equals quality, yet popular, successful, and respectable novelists, namely Charles Dickens, Anthony Trollope, Elizabeth Gaskell and Margaret Oliphant, were writing, printing, and distributing them. This study navigates a nexus of discourses about culture, literature, and writing to explore, delineate, and ascertain the implications of the contextual position of certain short stories. In particular, it identifies and characterizes a previously unexamined genre, here called the Market Story, in order to argue for the contingency and de-centring of processes and pronouncements of valuation. Market stories are defined by their relationship to a publishing industry that was actively creating a space for, demanding, and disseminating texts based on their potential to generate sales figures, draw attention to a particular organ, -

Calendar of Events

Calendar the November/December 2010 hrysler of events CTHE MAGAZINE OF THE CHRYSLER MUSEUM OF ART p 4 Exhibitions • p 6 News • p 8 Daily Calendar • p 11 Public Programs • p 15 Member Programs G ENERAL INFORMATION COVER Contact Us The Museum Shop Group and School Tours Stevens & Williams Open during Museum hours Stourbridge, England Chrysler Museum of Art (757) 333-6269 Covered Jar in the 245 W. Olney Road (757) 333-6297 www.chrysler.org/programs.asp Chinese Taste Norfolk, VA 23510 with Rock Crystal Phone: (757) 664-6200 Cuisine & Company Board of Trustees Engraving, ca. 1884 Fax: (757) 664-6201 at The Chrysler Café 2010–2011 Engraved by Joseph E-mail: [email protected] Wednesdays, 11 a.m.–8 p.m. Shirley C. Baldwin Keller (English, Website: www.chrysler.org 1880–1925) Thursdays–Saturdays, 11 a.m.–3 p.m. Carolyn K. Barry Blown, cut, and Sundays, 12–3 p.m. Robert M. Boyd Museum Hours engraved glass (757) 333-6291 Nancy W. Branch Museum purchase Wednesday, 10 a.m.–9 p.m. Macon F. Brock, Jr., Chairman Thursday–Saturday, 10 a.m.–5 p.m. Historic Houses Robert W. Carter Sunday, 12–5 p.m. Free Admission Andrew S. Fine The Museum galleries are closed each The Moses Myers House Elizabeth Fraim Monday and Tuesday, as well as on 323 E. Freemason St. (at Bank St.), Norfolk David R. Goode, Vice Chairman major holidays. The Norfolk History Museum at the Cyrus W. Grandy V Marc Jacobson Admission Willoughby-Baylor House 601 E. Freemason Street, Norfolk Maurice A. -

A House to Let

A House to Let Charles Dickens, et al The Project Gutenberg eBook, A House to Let, by Charles Dickens, et al This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: A House to Let Author: Charles Dickens Release Date: May 10, 2005 [eBook #2324] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-646-US (US-ASCII) ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A HOUSE TO LET*** Transcribed from the 1903 Chapman and Hall edition by David Price, email [email protected]. Proofed by David, Edgar Howard, Dawn Smith, Terry Jeffress and Jane Foster. A HOUSE TO LET (FULL TEXT) by Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, Elizabeth Gaskell, Adelaide Ann Procter Contents: Over the Way The Manchester Marriage Going into Society Three Evenings in the House Trottle's Report Let at Last Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. OVER THE WAY I had been living at Tunbridge Wells and nowhere else, going on for ten years, when my medical man--very clever in his profession, and the prettiest player I ever saw in my life of a hand at Long Whist, which was a noble and a princely game before Short was heard of--said to me, one day, as he sat feeling my pulse on the actual sofa which my poor dear sister Jane worked before her spine came on, and laid her on a board for fifteen months at a stretch--the most upright woman that ever lived--said -

Download Doc // a House To

I3Z9WSAPHMRQ » eBook » A House to Let Download Book A HOUSE TO LET CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. Paperback. Book Condition: New. This item is printed on demand. Paperback. 98 pages. Dimensions: 9.0in. x 6.0in. x 0.2in.A House to Let is a short story by Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, Elizabeth Gaskell and Adelaide Anne Procter. It was originally published in 1858 in the Christmas edition of Dickens Household Words magazine. Each of the contributors wrote a chapter and the story was edited by Dickens. A House to Let was the first collaboration between the... Download PDF A House to Let Authored by Wilkie Collins Released at - Filesize: 8.86 MB Reviews Very useful to all group of folks. This really is for all who statte there was not a worthy of reading. I am very happy to explain how this is the best pdf i have study inside my personal life and can be he greatest book for actually. -- Marcelle Homenick This type of publication is every thing and got me to seeking in advance plus more. I was able to comprehended every thing out of this created e ebook. I am easily could possibly get a satisfaction of reading a created ebook. -- Sonya K oss TERMS | DMCA TUNUGFQ6QKEX » Doc » A House to Let Related Books Short Stories 3 Year Old and His Cat and Christmas Holiday Short Story Dec 2015: Short Stories Too Old for Motor Racing: A Short Story in Case I Didnt Live Long Enough to Finish Writing a Longer One The Werewolf Apocalypse: A Short Story Fantasy Adaptation of Little Red Riding Hood (for 4th Grade and Up) The Way of King Arthur: The True Story of King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table (Adventures in History) Learn em Good: Improve Your Child s Math Skills: Simple and Effective Ways to Become Your Child s Free Tutor Without Opening a Textbook. -

George Augustus Sala: the Daily Telegraph's Greatest Special

Gale Primary Sources Start at the source. George Augustus Sala: The Daily Telegraph’s Greatest Special Correspondent Peter Blake University of Brighton Various source media, The Telegraph Historical Archive 1855-2000 EMPOWER™ RESEARCH Early Years locked himself out of his flat and was forced to wander the streets of London all night with nine pence in his The young George Augustus Sala was a precocious pocket. He only found shelter at seven o’clock the literary talent. In 1841, at the age of 13, he wrote his following morning. The resulting article he wrote from first novel entitled Jemmy Jenkins; or the Adventures of a this experience is constructed around his inability to Sweep. The following year he produced his second find a place to sleep, the hardship of life on the streets extended piece of fiction, Gerald Moreland; Or, the of the capital and the subsequent social commentary Forged Will (1842). Although these works were this entailed. While deliberating which journal might unpublished, Sala clearly possessed a considerable accept the article, Sala remembered a connection he literary ability and his vocabulary was enhanced by his and his mother had shared with Charles Dickens. In devouring of the Penny Dreadfuls of the period, along 1837 his mother had been understudy at the St James’s with the ‘Newgate novels’ then in vogue, and Theatre in The Village Coquettes, an operetta written by newspapers like The Times and illustrated newspapers Dickens and composed by John Hullah. Madame Sala and journals like the Illustrated London News and and Dickens went on to become good friends on the Punch. -

My Autobiography and Reminiscences

s^ FURTHER REMINISCENCES \V. p. FRITH. Painted by Douglas Cowper in 1838. MY AUTOBIOGRAPHY AND REMINISCENCES BY W. p. FKITH, E.A. CHEVALIER OP THE LEGION OP HONOR AND OP THE ORDER OP LEOPOLD ; MEMBER OP THE ROYAL ACADEMY OP BELGIUM, AND OP THE ACADEMIES OP STOCKHOLM, ^^ENNA, AND ANTWERP " ' The pencil speaks the tongue of every land Dryden Vol. II. NEW YORK HARPER & BROTHERS, FRANKLIN SQUARE 1888 Art Libraxj f 3IAg. TO MY SISTER WITHOUT WHOSE LOVING CARE OF MY EARLY LETTERS THIS VOLUME WOULD HAVE SUFFERED 3 {Dcbicfltc THESE FURTHER RE^IINISCENCES WITH TRUE AFFECTION CONTENTS. CHAPTER PAGE INTRODUCTION 1 I. GREAT NAMES, AND THE VALUE OF THEM ... 9 II. PRELUDE TO CORRESPONDENCE 21 III. EARLY CORRESPONDENCE 25 IV. ASYLUM EXPERIENCES 58 V. ANECDOTES VARIOUS 71 VI. AN OVER-TRUE TALE 102 VII. SCRAPS 114 VIII. A YORKSHIRE BLUNDER, AND SCRAPS CONTINUED. 122 IX. RICHARD DADD 131 X. AN OLD-FASHIONED PATRON 143 XI. ANOTHER DINNER AT IVY COTTAGE 154 XII. CHARLES DICKENS 165 XIII. SIR EDWIN LANDSEER 171 XIV. GEORGE AUGUSTUS SALA 179 XV. JOHN LEECH 187 XVI. SHIRLEY BROOKS 194 XVII. ADMIRATION 209 XVIII. ON SELF-DELUSION AND OTHER MATTERS . .217 XIX. FASHION IN ART .... - 225 XX. A STORY OF A SNOWY NIGHT 232 XXI. ENGLISH ART AND FRENCH INFLUENCE .... 237 XXII. IGNORANCE OF ART 244 Vlll CONTENTS. CHAPTER PAGE XXIII. ORATORY 253 XXIV. SUPPOSITITIOUS PICTURES 260 XXV. A VARIETY OF LETTERS FROM VARIOUS PEOPLE . 265 XXVI. MRS. MAXWELL 289 XXVII. BOOK ILLUSTRATORS 294 XXVIII. MORE PEOPLE WHOM I HAVE KNOWN .... 301 INDEX 3I5 MY AUTOBIOGEAPHY AND KEMINISCEKCES. -

Ethical Metafiction in Dickens's Christmas Hauntings

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2013-06-06 Ethical Metafiction in Dickens's Christmas Hauntings Mark Brian Sabey Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Sabey, Mark Brian, "Ethical Metafiction in Dickens's Christmas Hauntings" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 4045. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4045 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Ethical Metafiction in Dickens’s Christmas Hauntings M. Brian Sabey A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Steven C. Walker, Chair Jamie Horrocks Paul A. Westover Department of English Brigham Young University June 2013 Copyright © 2013 M. Brian Sabey All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Ethical Metafiction in Dickens’s Christmas Hauntings M. Brian Sabey Department of English, BYU Master of Arts Many critics have examined metanarrative aspects of Dickens’s writing, and many have studied Dickens’s ethics. None, however, has yet assessed the ways in which Dickens’s directly interrogates the ethics of fiction. Surprisingly philosophical treatments of the ethics of fiction take place in A Christmas Carol and A House to Let, both of which turn the ghost story of the traditional winter’s tale to metafictional purposes. No one has yet dealt with Dickens’s own meta-commentary on the ethics of fiction with the degree of philosophical nuance it deserves. -

Collaborative Dickens Contents

Collaborative Dickens Contents List of Illustrations ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1 Writing Christmas with “a Bunch of People” (1850–51) 20 2 Reading in Circles: From Numbers to Rounds (1852–53) 34 3 Orderly Travels and Generic Developments (1854–55) 58 4 Collaborative Survival and Voices Abroad (1856–57) 78 5 Moving Houses and Unsettling Stories (1858–59) 102 6 Disconnected Bodies and Troubled Textuality (1860–62) 126 7 Bundling Children and Binding Legacies (1863–65) 159 8 Coming to a Stop (1866–67) 185 Conclusion 219 Appendix A. The Complete Christmas Numbers: Contents and Contributors 227 Appendix B. Authorship Percentage Charts 233 Notes 235 Bibliography 263 Index 275 qvii I ntroduction For those who think of Charles Dickens as a professional and personal bully, the phrase “collaborative Dickens” may sound like an oxymoron or an overly generous fantasy. For those who associate only A Christmas Carol with the phrase “Dickens and Christmas,” the phrase “Dickens’s Christmas numbers” may act as a reminder of the seemingly infinite number ofCarol adaptations. There is, however, a whole cache of Dickens Christmas literature that has little to do with Ebenezer Scrooge and is indeed collaborative. Readers and scholars do not usually regard Dickens as a famous writer who placed his voice in conversation with and sometimes on a level with fairly unknown writers. And yet this Dickens, a significant collaborative presence in the Vic- torian period, is one that I have found repeatedly while editing and studying the literature he produced for Christmas. Between 1850 and 1867, Dickens released a special annual issue, or number, of his journal shortly before Christmas. -

Dickens by Numbers: the Christmas Numbers of Household Words and All the Year Round

Dickens by Numbers: the Christmas Numbers of Household Words and All the Year Round Aine Helen McNicholas PhD University of York English May 2015 Abstract This thesis examines the short fiction that makes up the annual Christmas Numbers of Dickens’s journals, Household Words and All the Year Round. Through close reading and with reference to Dickens’s letters, contemporary reviews, and the work of his contributors, this thesis contends that the Christmas Numbers are one of the most remarkable and overlooked bodies of work of the second half of the nineteenth century. Dickens’s short fictions rarely receive sustained or close attention, despite the continuing commitment by critics to bring the whole range of Dickens’s career into focus, from his sketches and journalism, to his late public readings. Through readings of selected texts, this thesis will show that Dickens’s Christmas Number stories are particularly powerful and experimental examples of some of the deepest and most recurrent concerns of his work. They include, for example, three of his four uses of a child narrator and one of his few female narrators, and are concerned with childhood, memory, and the socially marginal figures and distinctive voices that are so characteristic of his longer work. But, crucially, they also go further than his longer work to thematise the very questions raised by their production, including anonymity, authorship, collaboration, and annual return. This thesis takes Dickens’s works as its primary focus, but it will also draw throughout on the work of his contributors, which appeared alongside Dickens’s stories in these Christmas issues. -

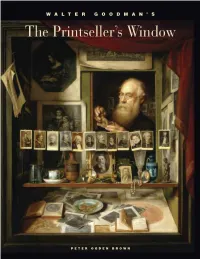

The Printseller's Window: Solving a Painter's Puzzle, on View at the Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester from August 14–November 8, 2009

WALTER GOODMAN’S WALTER GOODMAN’S The Printseller’s Window The Printseller’s Window PETER OGDEN BROWN PETER OGDEN BROWN WALTER GOODMAN’S The Printseller’s Window PETER OGDEN BROWN 500 University Avenue, Rochester NY 14607, mag.rochester.edu Author: Peter O. Brown Editor: John Blanpied Project Coordinator: Marjorie B. Searl Designer: Kathy D’Amanda/MillRace Design Associates Printer: St. Vincent Press First published 2009 in conjunction with the exhibition Walter Goodman’s The Printseller’s Window: Solving a Painter’s Puzzle, on view at the Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester from August 14–November 8, 2009. The exhibition was sponsored by the Thomas and Marion Hawks Memorial Fund, with additional support from Alesco Advisors and an anonymous donor. ISBN 978-0-918098-12-2 (alk. paper) ©2009 Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester. All rights reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation, no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded, or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Every attempt has been made to identify owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent editions. Cover illustration: Walter Goodman (British, 1838–1912) The Printseller’s Window, 1883 Oil on canvas 52 ¼” x 44 ¾” Marion Stratton Gould Fund, 98.75 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My pursuit of the relatively unknown Victorian painter Walter Goodman and his lost body of work began shortly after the Memorial Art Gallery’s acquisition of The Printseller’s Window1 in 1998. -

Your Guide to the Classic Literature CD Version 4 Electronic Texts For

Your Guide to the Classic Literature CD Version 4 Electronic texts for use with Kurzweil 1000 and Kurzweil 3000. Your Guide to the Classic Literature CD Version 4. Copyright © 2003-2010 by Kurzweil Educational Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. Eleventh printing, January 2010. Kurzweil 1000 and Kurzweil 3000 are trademarks of Kurzweil Educational Systems, Inc., a Cambium Learning Technologies Company. All other trademarks used herein are the properties of their respective owners and are used for identification purposes only. Part Number: 125516 UPC: 634171255169 11 12 13 14 15 BNG 14 13 12 11 10 Printed in the United States of America. 25 Prime Park Way . Natick, MA 01760 . (781) 276-0600 2-0 Introduction Kurzweil Educational Systems is pleased to release the Classic Literature CD Version 4. The Classic Literature CD is a portable library of approximately 1,800 electronic texts, selected from public domain material available from Web sites such as www.gutenberg.net. You can easily access the CD’s contents from any of Kurzweil Educational Systems products: Kurzweil 1000™, Kurzweil 3000™ for the Apple® Macintosh® and Kurzweil 3000 for Microsoft® Windows®. Some examples of the CD’s contents are: Literary classics by Jane Austen, Geoffrey Chaucer, Joseph Conrad, Charles Dickens, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Hermann Hesse, Henry James, William Shakespeare, George Bernard Shaw, Leo Tolstoy and Oscar Wilde. Children’s classics by L. Frank Baum, Brothers Grimm, Rudyard Kipling, Jack London, and Mark Twain. Classic texts from Aristotle and Plato. Scientific works such as Einstein’s “Relativity: The Special and General Theory.” Reference materials, including world factbooks, famous speeches, history resources, and United States law. -

Classic Literature Guide

Your Guide to the Classic Literature Collection. Electronic texts for use with Kurzweil 1000 and Kurzweil 3000. Revised April 25, 2019. Your Guide to the Classic Literature Collection – April 25, 2019. © Kurzweil Education, a Cambium Learning Company. All rights reserved. Kurzweil 1000 and Kurzweil 3000 are trademarks of Kurzweil Education, a Cambium Learning Technologies Company. All other trademarks used herein are the properties of their respective owners and are used for identification purposes only. Part Number: 125516. UPC: 634171255169. 11 12 13 14 15 BNG 14 13 12 11 10. Printed in the United States of America. 1 Introduction Introduction Kurzweil Education is pleased to release the Classic Literature Collection. The Classic Literature Collection is a portable library of approximately 1,800 electronic texts, selected from public domain material available from Web sites such as www.gutenberg.net. You can easily access the contents from any of Kurzweil Education products: Kurzweil 1000™, Kurzweil 3000™ for the Apple® Macintosh® and Kurzweil 3000 for Microsoft® Windows®. The collection is also available from the Universal Library for Web License users on kurzweil3000.com. Some examples of the contents are: • Literary classics by Jane Austen, Geoffrey Chaucer, Joseph Conrad, Charles Dickens, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Hermann Hesse, Henry James, William Shakespeare, George Bernard Shaw, Leo Tolstoy and Oscar Wilde. • Children’s classics by L. Frank Baum, Brothers Grimm, Rudyard Kipling, Jack London, and Mark Twain. • Classic texts from Aristotle and Plato. • Scientific works such as Einstein’s “Relativity: The Special and General Theory.” • Reference materials, including world factbooks, famous speeches, history resources, and United States law.